One of the biggest points of contention among those selling life rafts, and a point of confusion among those buying them, is what they are made of and how they are constructed. We requested material samples from all of the manufacturers in Practical Sailor’s recent three-part evaluation (May 1, June Double and July 1, 2000). Six supplied them; Survival Products, Plastimo and Viking did not. Then the samples were tested for abrasion and puncture resistance. We also spoke with engineers and service stations to get the rest of the story.

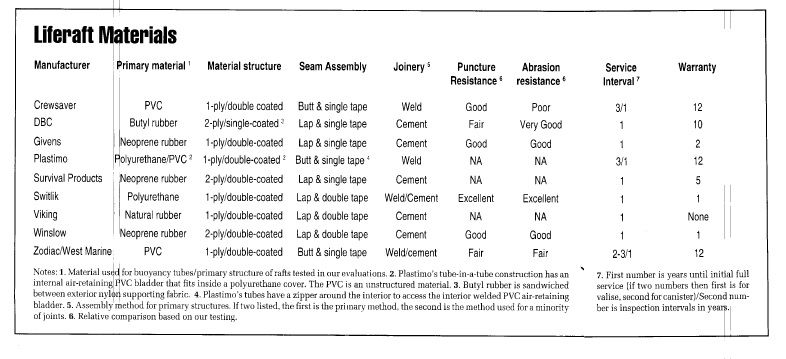

The chart below lists the materials and construction techniques and our test results.

Materials fall into three broad categories—rubbers, polyurethanes (PU), and polyvinylchlorides (PVC), with a variety of different compositions among those. None of these materials is perfect; each has its advantages and disadvantages from a performance and cost standpoint.

In addition to the coating, which provides air retention and in some cases abuse resistance, there is also the base construction material, the “cloth” that provides strength and structure. The number of base plies and coatings has an impact on ultimate material strength and abuse resistance. Everything is a compromise and the manufacturers must balance the various attributes to arrive at a fabric that provides adequate performance, functionality, manufacturability and economy.

In terms of construction, two issues arise, both revolving around how pieces are joined to assemble the raft. Traditionally, material is cemented together. The move to PU and PVC materials has been prompted in large part by a desire to reduce or eliminate the problems associated with the glues (cements) and solvents—health hazards and manufacturing process difficulties. PU and PVC can be welded using a variety of methods, usually by applying heat and pressure. The process has its own problems and it has taken a while for the industry to figure out how to do it properly.

Some rafts use a combination of assembly methods. Either method can provide a bond stronger than the material itself; either can also be done poorly with disastrous results. Neither is foolproof. Welding lends itself to mechanical production and potential production economies.

The seam itself is the most likely failure point and different manufacturers use different techniques. Lap seams are most common, but some use a butt seam, which we feel is inherently less robust. Switlik, Viking, and Winslow apply seam tape on both the interior and exterior, which we prefer for the added reinforcement and security this generally provides.

Natural rubber’s most noticeable drawback seems to be its bad odor; but it is resistant to abuse and service life can exceed 15 years. The synthetic rubbers, neoprene and butyl, generally last as long or longer and are inherently more resistant to degradation from the elements, fungus growth, and contamination. If properly cared for and serviced, neoprene rafts have been known to last 15-20 years.

PU is generally more puncture- and abrasion-resistant, but by all reports will have a shorter life span and is somewhat more susceptible to environmental degradation—heat and fungus. Ten to 15 years is about all you should expect from a polyurethane raft, the experts tell us, though the jury is still out.

PVC is neither as strong, long-lived, or tough as the others, but is generally the least expensive, hence its appeal. PVC may not last even 10 years under anything less than perfect conditions. Service centers we spoke with would not comment on the record about the problems they’ve had with PU and PVC materials for fear of reprisals from the manufacturers.

All PU and PVC raffs are vacuum-packed, however, and this will extend life expectancy.

We didn’t test for ultimate tensile strength of the fabrics because there is no indication that this is a proximate cause for life raft failures in use. Nor did we, because of the difficulties in performing such tests, test for the effects of exposure.

The heaviness of a material is not necessarily a good indication of its ultimate suitability. If that were true, we’d all still be sailing with canvas sails. By the same token, care must be taken that lighter-weight or lower-cost materials are up to the task. Inevitably, there are tradeoffs. Our top-rated rafts are all constructed of materials that appear to be adequate. Switlik’s PU takes top honors by a significant margin, but it should be noted that DBC, Givens and Viking all use the same buoyancy tube material on their yachting rafts as in their SOLAS/USCG-approved rafts (Givens is not currently producing approved rafts; it is awaiting certification of its new factory). In our tests, Winslow’s neoprene material was on par with Givens’ SOLAS-grade material.

The material is only one part of the raft, albeit an important part. The best material and construction techniques in a poorly designed raft won’t necessarily save your life, but inadequate materials or construction can doom any raft. Actual in-use failures of rafts seem to revolve around construction and maintenance issues.

That brings us to maintenance. A life raft, like all safety appliances, must be maintained. Sadly, only a small percentage of yachting rafts are adequately maintained. We recommend you follow the manufacturer’s suggested service schedule. While some vacuum-packed rafts allow up to two or three years before the first full service, even these require a yearly check to ensure the raft’s packaging is intact. If not vacuum-packed, and after the initial period is over for those that are vacuum-packed, rafts are supposed to be re-packed annually. The older the raft, the more critical annual servicing becomes. Federal law requires the gas cylinder to be hydro-tested every five years. Avoid unauthorized service facilities and never, in our opinion, use a facility that won’t allow you to be present for the re-pack. Some will even videotape the procedure for you if you can’t be present.

Warranties run the gamut, from none to 12 years, with the least expensive rafts carrying the longest warranties, suggesting that marketing is as much a factor as anything. Read the warranty carefully. The longer ones all have fine print requiring specific performance on your part, including strict abidance to the manufacturer’s service intervals.

Conversely, those manufacturers without a warranty or with short ones, including our top-rated rafts, have generally sterling reputations for standing behind their product. Ultimately, that’s more important than a piece of paper, as far as we are concerned.

Finally, for your own protection, be sure to fill out the registration card that comes with your raft. It’s the only practical way to provide direct notification if a recall is necessary.