It only makes sense that a 41-foot boat will be significantly faster than a 37-foot sistership, right?

That a 41-footer will have significantly larger living spaces and greatly improved accommodations?

And, that the bigger boat will have more room on deck for entertaining purposes?

Or does it?

With the assistance of Tim Jackett, general manager and chief designer at Tartan Yachts, we compared his company’s most popular models, the 4100, which has been in production for four years, and the recently introduced 3700.

Our findings were intriguing: We discovered that a 10% increase in boat size doesn’t necessarily translate into a significant increase in speed or creature comforts.

The results, in some cases, even surprised Jackett.

The Company

Tartan Marine grew out of Grand River, Ohio boatbuilder Douglass & McLeod, which in the early 1960s formed a partnership with Charles Britton to build the Tartan 27, designed by Sparkman & Stephens. During the 1980s the company bounced around among several owners (John Richards and Jim Briggs, Baltic Holding Corp., NavStar Marine, Polk Industries), but managed to survive. It currently prospers under ownership that recapitalized the organization as Fairport Yachts, Inc. The company acquired the C&C label in 1998, and added a “strictly performance” product to its portfolio. Both lines are produced at a factory in Fairport Harbor, Ohio.

Like Sabre and Pacific Seacraft, Tartan boats appeal to sailors seeking a combination of speed, comfort, styling and above average construction, and who are willing to pay more for it. Tartan boats are described as “moderate displacement performance cruisers.”

Since its reorganization the company has grown and now has 150 employees who build 90-100 boats a year. Following the introduction in 1999 of the C&C Express 101 (see October 1, 1999), the company’s production has been split fairly evenly between the two lines; in 2000, roughly 60% of the boats produced are the Tartan 3500, 3700, and 4100.

The company’s rebound was aided by establishment of a 21-dealer network that covers both coasts.

Design

When describing Tartan boats, Jackett said that they “share similar design and performance targets, are like products, and are designed to be well-behaved.”

To meet his goal of building a “legitimate performance cruiser,” he said that design starts with upwind performance as a benchmark. “We want efficiency and comfortable motion, sail-carrying ability, underwater cleanness, and strength.”

When he began conceptualizing the 3700 he faced the challenge of matching the interior volume and speed of the 4100 in a boat 4 feet shorter.

“Two couples going cruising are going to bring the same amount of gear, regardless of the size of the boat,” he said.

To accomplish this, the bow entry angle of the 3700 is not as fine as the 4100, which allows for more space forward, and the entire hull is rounder, which produces more interior volume. A wider stern gives stability when sailing off the wind. Maximum beam is 12′ 8″ and beam at the stern is nearly 11′.

“A flat-bottomed boat, like the 4100, is stickier in the water in light air conditions,” Jackett said. Though the 3700 has more proportional wetted surface area, he predicts good light air performance.

The sail area/displacement, beam/displacement, and displacement/length ratios of the 4100 and 3700 are nearly identical (see table of specifications). The range of positive stability is given as 125°, better than the 120° minimum we think is prudent for bluewater sailing.

“We’re also trying to fit ‘people shapes’ on a shorter waterline,” he said, describing flat sections where floors meet the hull, for instance, and berths large enough to sleep adults comfortably.

Three keel options are available for both boats—deep fin, moderate draft beavertail and shoal draft centerboard. Ballast is lead. Rudders are efficient, high aspect ratio spades.

Construction

The hand laid-up hulls are solid fiberglass below the waterline and cored with Baltek balsa above the waterline. Alternating layers of strand mat and unidirectional E glass make up the laminate and are vacuum-bagged. “Windows” where deck hardware and stanchions will be installed are solid fiberglass. Isophtalic polyester and vinylester resins are used to help prevent blistering.

The deck is balsa-cored.

Rather than using fiberglass pans and liners, bulkheads are constructed of pressure laminate and tabbed to the hull with mat and roving, as is the floor grid. We think this is a superior way to build boats; Tartan is one of the few production builders left to use built-up wood interiors. All semi-custom and custom builders like Hinckley, Morris and Alden do, too.

The hull-deck joint follows the company’s 20-plus-year practice of bedding the seam with 3M 5200 and fastening with stainless steel bolts through predrilled holes in an aluminum bar laid between the hull and deck.

The rudders are foam-cored fiberglass with 304 stainless steel rudderstocks. This common construction makes it difficult to keep water out, due to the different coefficients of expansion of fiberglass and steel. For new boat construction, we think there is a lot of merit in composite rudderstocks. In any case, 316 stainless would be preferable to 304. For a more detailed discussion of foam-core rudders, see the January 15, 2000 issue.

Deck

Because the deck plans of the two boats are nearly identical, the primary differences are overall dimensions.

High quality hardware is supplied by Lewmar and Harken; the portlights are by Hood Yacht Systems.

Both boats have double-spreader rigs with slightly swept-back spreaders, which make for narrow sheeting angles to improve upwind performance. The backstay is split for easier access to the stern swim steps. The mast and boom are made by Offshore Spars.

Movement about the deck is unimpeded; the side decks are 24″ wide and clean. Chainplates are inboard near the cabin sides. The double lifelines, stanchions and pulpits are 27″ high. Handrails on each side of the cabin top are teak.

There’s adequate light on cloudy days, and ventilation during steamy summer months. Both boats have six stainless portlights on each side of the cabin, large hatches over living areas and the head, and Dorade vents forward of the mainsheet traveler.

Deck hardware is well organized for casual cruising or buoy racing. Sail controls are led aft. A typical equipment list includes Lewmar sheet lead blocks on Lewmar tracks running through Harken turning blocks to Spinlock XT sheet stoppers. The winches are by Harken and most are two-speed self-tailers.

Anchor stowage is in two compartments with adequate space for two anchors and rope or chain rode. The bow roller on the 3700 is a single stainless steel plate; the 4100 is equipped with a twin roller offset from the centerline.

The major difference between the decks of the two boats is in the cockpit, where the 4100 enjoys an advantage in centerline length—78″ compared to 56″ for the smaller boat.

Cockpit seating on the 3700 is on comfortable 52″ by 18″ seats, contoured to provide excellent lumbar support.

Both boats are equipped with destroyer-style wheels, Whitlock Steering Systems and Ritchie compasses. The 4100 is equipped with a handy teak table that stores flush against the pedestal. Engine controls are within easy reach of the helmsman.

Moving forward from the helm on the 3700 requires stepping over the aft corner of a seat, which is somewhat annoying.

Because of the aft cabin, the port seat lockers are only 12″ deep (but 52″ wide and 7′ long), and are used for installation of a heater, built-in battery charger, and manual bilge pump, which share space with dock gear. The emergency tiller also is stowed here.

Accommodations

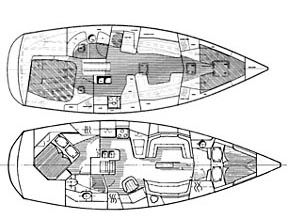

Both boats have nearly identical accommodations, though the layouts for galley, head and nav station are reversed.

Why?

“I hadn’t noticed or thought about it,” said Jackett. “I start with a clean sheet of paper for every design and try to execute a concept.”

The joinerwork reflects fine craftsmanship—cherry wood surfaces are smooth and nicely varnished, and fiberglass surfaces are smooth and shiny.

Though the 4100 is 4′ longer on deck, that doesn’t translate to a dramatic difference in dimensions belowdecks. The 4100’s saloon measures 9.75′ long and 7.5′ wide, compared to the 8.8′ by 6.7′ dimensions of the 3700.

Headroom in the main cabin of the 3700 is 6′ 4″ inches; in the 4100 headroom is 6′ 5″.

The settees in both boats are nearly identical in length—70″, though the seats in the 4100 are wider.

Similarly, the dining tables are near twins. With folding leaves in the upright position, each is about 44″ wide and 34″ long.

“The first ten 3700s had pipe berths amidships,” Jackett said, “but that’s not what the market wants.”

The navigation station on the 4100 is located to starboard facing outboard, and is to port facing forward on the 3700; the latter arrangement is our first choice. Both provide 25″-27″ x 35″-39″ work surfaces.

Another of Jackett’s rules: “Every inch of extra space I can find in staterooms and heads goes into the main cabin and galley.”

His newest designs have an island on the centerline at the foot of the companionway opposite the L-shaped galley. It provides a counter where the cook can work at a pivot point of the boat when heeled.

The island on the 4100 is 48″ x 42″, compared to the smaller 27″ x 15″ island on the 3700. Both are equipped with double stainless steel sinks. The galley can be entirely enclosed by lifting a tilt-up counter at the end of the island. Countertops are Formica, though a “solid surface” material similar to Corian™ is an option.

Both galleys are equipped with Force 10 3-burner stoves. Storage areas on shelves and in drawers is adequate for extended cruising.

Both boats have staterooms fore and aft that are furnished with queen-sized berths.

Interestingly, when we asked Jackett to compare the two, he made a discovery.

“The aft cabins in the 3700 and 4100 are identical. That was a surprise,” he said. Both are equipped with a solid door, teak and holly sole, vanity, cedar lined cabinets and opening ports.

Standing headroom in the aft cabins exceeds 6′.

Berths in the forward cabins are nearly identical. Both measure approximately 82″ on the centerline, and are 77″ wide. Headroom in the forward cabin of the 3700 is 6′ 2; in the 4100 it’s 6′ 3″.

The head receives special attention since Jackett feels that the minimum acceptable size for a shower is 26″ square. Meeting that objective required slightly offsetting the companionway on the 3700.

The head on the 3700 is 67″ long, compared to the head on the 4100, which measures 76″. Both are approximately 48″ wide and have 6′ 3″ headroom. They are well-ventilated by opening portlights and hatches. A neat wrinkle is a unique folding shower door that, when not in use, attaches out of the way to the hull. We’d guess that the showers will double as hanging lockers for wet foul weather gear.

Performance

With assistance from Jim Long of H & S Yacht Sales of Alameda, California, who lives aboard a 4100, we tested her in varied conditions on San Francisco Bay. We were not able to sail the 3700.

The 4100 motored easily into a stiff breeze at 7.5 knots with the Yanmar 50 rumbling at 2500 RPM; boat speed increased to 8 knots at 3,000 RPM. A well-insulated engine compartment allowed us to converse belowdecks at normal voice levels.

Initially sailing on flat water in 10 knots of wind, she sailed to within 30°-35° of apparent wind and boat speed was 4.5-5 knots.

When wind speed increased to 15 knots, boat speed increased to 6 knots, and she developed a hint of weather helm. By our estimates, she tacked through 90°. When the bay grew lumpy, she felt buoyant but did not hobbyhorse.

Footing off to 65° in 18 knots of wind, speed jumped to 8-plus knots.

Admittedly overcanvassed, we carried a full main and 110% genoa in 22 knots of wind and saw boat speed increase to 9.5 knots on a close reach, even with the traveler down.

Sailing at 120° of apparent wind with the genoa slightly blanketed, boat speed held steady at 8.5 knots; she was flat, and the crew was comfortable.

Conclusion

Considering the significant price differential between the two boats, potential buyers can evaluate the 3700 and 4100 using several criteria. Among them:

Performance. Since we were unable to test the 3700 we can only speculate that, based on Jackett’s design skills and statistical performance indicators, the boats will perform similarly.

The 4100’s 3′ longer waterline will be most noticeable on long downwind legs; the longer boat would travel the 2,000 miles from San Francisco to Honolulu at least one day faster than the 3700.

Intended use. Both boats are well constructed, so we’d sail either across the ocean. However, the 4100 would be our first choice; she’s heavier so will be more comfortable offshore, and has a longer waterline.

Creature comforts. The main cabins and staterooms are nearly identical. Both will sleep 4-6 comfortably. Galleys are large enough for extended cruising. Though smaller, the head on the 3700 is large enough for average-sized adults. The most significant difference between the two is in the additional cockpit space of the 4100.

In some respects, it doesn’t seem that 4 feet buys you all that much, but though perhaps subtle, differences do exist, and only you can say whether they are worth $65,000.

As far as comparison with other boats, a Dehler 36 sells for $141,000, a Moody 42 goes for about $260,000 and a Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 43DS for $203,000. We think that when you look deep into the Tartans, they compare very favorably.

Contact- Fairport Yachts, 1920 Fairport Nursery Rd., Fairport Harbor, OH 44077; 440/354-3111, www.tartanyachts.com.