Some years ago – never mind how long precisely – Rodney Johnstone, a Connecticut schoolteacher, changed careers and became an ad salesman for a marine magazine. Then, still unsatisfied, he enrolled in the Westlawn School of Yacht Design. He didn’t graduate, but he did became so successful designing the line of J-Boats that the school gave him an honorary degree so it could use his name in advertisements.

This Horatio Alger story begins appropriately enough with rags, in this case, Ragtime, the prototype of the J/24 Rod built in his garage. During its first season of racing on Long Island Sound, 1976, the flat-bottomed speedster took 17 of 19 starts. Rod’s brother Robert (Bob) was marketing manager for Alcort/AMF, and asked his bosses if they’d like to build Ragtime on a production basis. In one of the few missed opportunities ever to occur in the sailing industry, an industry where “no” is usually the smart choice, they indeed said no.

Ha. So Bob did what any self-respecting man would do – he quit. J-Boats was formed by the brothers in 1977, and Everett Pearson’s TPI began building the J/24. By 1986 more than 4,200 had been sold. By 1997, there were more than 5,200.

The appeal of the J/24 is partly due to just those numbers; there are large, competitive fleets around the U.S. and the world. J-Boats licensed builders in Australia, Japan, Italy, England, France, Brazil and Argentina. But it’s more than that. The J/24 is an affordable option for people who want to race one-designs bigger than daysailers, but don’t have a hundred grand a year and more for grand prix racing. If you really want to do Key West Race Week, the J/24 can be trailered behind the family car.

While the J/105 isn’t nearly as trailerable as the 24 (an ad for the boat states flatly that it’s “for people who live near where they sail”) it does echo that theme of maximum bang and flexibility for the buck for people who intend to sail rather than sit still.

Introduced in 1992, the J/105 isn’t alone in the sport-boat genre, but it was certainly a progenitor of the species. PS editor Doug Logan, reviewing the boat for Sailing World soon after its appearance, saw a confluence of ideas that had been expressed in widely different types of boats – like Bill Lee sleds, Farrier’s trimarans, and Schumacher’s racer/cruisers – coming together in the J/105. The staggering idea at the time was the flat rejection of interior volume and cushiness in favor of simplicity, performance, and good looks. And this in a boat that was intended to cruise at least a bit, as well as race as a one-design. It was truly a bold move on Rod Johnstone’s part – and it has worked, though more on the racing side than on the cruising side. In its 10-year production run, more than 500 J/105s have been built.

The Design

Like most other J-Boats, the 34-1/2-foot, 7,750-pound J/105 is for people who enjoy speed and responsiveness. If you drive a Lincoln Town Car, buy a Tartan 4600. If you drive a Boxster, buy a J/105.

Anyone who has planed a daysailer knows the thrill of getting the hull up out of the water and boogeying. “Now,” designers like Rod Johnstone must have mused, “if only you could do that on a bigger keel boat.”

The speed available in a keelboat today was almost unthinkable before George Hinterhoeller, who no doubt had the same musings, designed and built his breakthrough Shark 24, way back in 1959. One Shark averaged more than 10 knots in an 80-mile race.

Rod Johnstone gets speed the same way Hinterhoeller did, with light weight, a flattish bottom, and a big rig. The J/105’s displacement/length ratio (D/L) is just 135, which makes it a very light displacement boat, and a sail area/displacement ratio (SA/D) of 24. These numbers make even the J/35, arguably one of the most successful mid-size racers of the modern era, look tame by comparison: D/L of 174 and SA/D of 21.

Overhangs are minimal and the waterline is long, at 29′ 6″. Beam is generous at 11′ for good form stability, draft is deep (6′ 6″) for ultimate stability, freeboard is low to reduce windage, and the cockpit is long, so there’s room for the crew, whether racing or just fooling around. The seats are 6′ 5″, sufficient yardage to sleep on. A 5′ 6″ shoal keel is available, and the one of choice in areas like the Chesapeake Bay. The limit of positive stability (LPS) is given at between 125° and 127° for shoal draft models, and about 130° for the deep keel. These exceed the generally accepted minimum of 120° for offshore sailing.

The J/105 has the same bow as the J/80, J/90 and others in the line; that is, a minimally raked profile with more curve and not as much “plumbness” (if there is such a word) on paper as appears in the water. From a purely aesthetic point of view, the line isn’t that interesting, but here form follows function. It does what it’s supposed to. The reverse transom has a molded cavity with ladder for swimming and boarding.

The keel is a deep, narrow fin with a slightly raked leading edge. You don’t want to hit a rock with this configuration, as you’re unlikely to ride over it. And if you do, check the floors under the cabin floorboards to see if you’ve wrenched anything.

The cabin is low profile, befitting a performance boat, with just two windows per side.

The rig is fractional, to permit bending the mast for optimal sail shape.

Construction

All J-Boats are built by TPI in Warren, Rhode Island, using the patented SCRIMP process. We’ve written about it before. In a nutshell, the fiberglass structures, principally the hull and deck, are laid up dry; that is, without resin. Layers of biaxial fiberglass fabric are laid into the mold, then sealed in a plastic “envelope” or bag as it were. A polypropylene woven fabric is spread on top of the laminate so there’s room for the resin to migrate vertically. When a vacuum is applied, air is sucked out of the envelope and resin is drawn in through a network of feeder tubes. This enables the builder to achieve a 70:30 glass-to-resin ratio, thought by many to be the ideal mix (some think it’s a little thin on the resin, preferring 65:35 or even 60:40).

With so little resin in the laminate, a core is definitely required to restore stiffness. J-Boats and TPI favor Baltek end-grain balsa, in this case its AL600 product. There are on the owners’ website a few complaints about print-through (seeing the pattern of the underlying fiberglass through the gelcoat) and flat spots where gelcoat is nearly absent.

As an aside, a major benefit of closed-molding techniques, in which the chemical reaction of the resin and catalyst takes place inside a bag and the resultant gases are exhausted directly out of the building, is a much cleaner air environment for the worker – and fewer headaches for the builder trying to meet EPA and OSHA guidelines for volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

TPI was a pioneer in studying and offering anti-blister protection. Today it uses a vinylester resin from Interplastic as an outer coat, under the gelcoat. A 10-year warranty against blistering is given.

The hull is stiffened by fore-and-aft and transverse solid glass hat sections molded with the hull at the time of initial lay-up. Before hull #156, these keel stringers and floor members were solid glass tabbed in after the hull was molded. The new method avoids secondary bonding, which is not as strong, where the beams (often wood or foam) are glassed to the finished hull. A superior secondary bond is achieved when the hull resin is still “green,” but nothing beats laying everything up together.

The main structural bulkhead is tabbed to the hull and deck, which is far preferable to the all-too-common practice of fitting the bulkhead into a molded groove in the headliner.

The keel stub is fiberglass and the ballasted bulb is lead.

The balanced spade rudder is fiberglass, as is the rudderpost, which is laid up with a quadraxial fabric. There are upper and lower bearings, and both have been a source of aggravation for many owners. According to the J/105 owners’ website, the bearings are aluminum, which corrode when in contact with the copper in bottom paint. Jeff Johnstone says they have a three-to-five year life, “sometimes even shorter if sacrificial zincs were allowed to dissolve, or if the Mylar spacer between the stainless and aluminum was removed, or if there was bottom paint on metallic parts of bearing, or simply if the bearing was not regularly rinsed out with fresh water a few times per season.”

Some owners have been replacing them with Harken plastic bearings, but now other sources must be found because Harken is no longer making bearings. The retrofit is not an easy job, say the owners who’ve done it.

Standard steering is a laminated wood tiller with Spinlock hiking stick. Wheel steering is optional, and boats with it command slightly higher resale prices. At least one owner said a tiller-steered boat can be hard to handle in heavy weather, but it’s hard to beat the feel of a tiller, and its simplicity must be admired.

Another steering-related problem has been the emergency tiller. Some owners say their tiller attaches at right angles to the centerline, so that when the rudder is centered, the tiller is hard to port. Other owners said their tiller didn’t fit when the boat was commissioned. These problems are correctable and should be checked out on purchase, new or used.

The Bomar hatch on the foredeck has been a source of aggravation. It’s opened when changing sails, and when laid flat on deck the welds in the frame are prone to cracking. (This stainless steel hatch is of good quality, but not as good as Bomar’s cast aluminum series of hatches). At first Bomar thought they should take responsibility and replaced a number at no cost. When it was determined that deck camber and opening past 180° combined to cause the failures, a deal was worked out with J-Boats to offer for $35 a bumper (to prevent opening the hatch beyond 180°) and a weld repair kit.

Remaining complaints include failure of cockpit seat locker hasps, cove stripes that are not straight or not of a uniform width, or that there are scribe marks for a cove stripe that doesn’t exist.

Interior

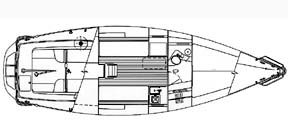

The accommodation plan is straightforward with a 7′ V-berth in the bow. Moving aft there’s an enclosed head with optional shower, and a hanging locker. The split galley is just aft of the main bulkhead, with a nav table to port and a stainless steel sink and space for an optional one-burner Origo alcohol stove to starboard. The ice box is actually a 54-quart portable cooler kept under the companionway ladder. Obviously it can’t be as well insulated as a built-in icebox, but it does save weight, and that’s the operative concept here. The portable freshwater tank holds just 5 gallons.

Opposing 6-1/2′ settee berths are port and starboard, with stowage bins outboard. These have gray vinyl trim and cold-molded teak cap moldings. Quarter berths (one or two) are optional, and seem to be favored by those owners who have them, though Johnstone says few boats are ordered that way. Length is 6-1/2′.

The trim theme is light and easy maintenance. The overhead and ceilings (hull sides) are covered with vinyl. Seat cushions are upholstered with Sunbrella. If you spring for the optional cockpit cushions they can double as backrests for the settees; they certainly increase comfort.

Other options include automatic electric bilge pump, shore power, cockpit/cabin table, sink in the head countertop, 20-gallon freshwater tank under the starboard berth, utensil drawer in galley, and a chart drawer under the nav table big enough to hold Chart Kits. They all sound nice to have, but together must add several hundred pounds.

The standard forward portlights are fixed, but you can have opening ones with screens for an extra charge. It’s also possible to have two ports in the aft face of the cabin trunk, either side of the companionway.

The interior is simple, and therein lies its attractiveness. Too many boats grow overly complicated as owners try to replicate the comforts of home. The J/105 resists that urge and rewards the owner with more time sailing (faster sailing at that), and less time fixing things.

The original floorboards were said to be weak by many owners. Many rotted when water entered the exposed end grain of the plywood. The problem was caused by the shallow bilge (a drawback of flat-bottom boats); when the boat heeled, the bottom of the boards got wet. Later, the plywood was covered with a plastic, but some of these $700 boards delaminated because the end grain still wasn’t sealed. Now, Johnstone says, “The standard for the last three years has been the Wear-rite synthetic teak and holly sole, which is used on a lot of charter boats in the Caribbean and is much more forgiving of punishment.” J-Boats seems anxious to correct such problems and customer service seems to be quite good.

For many people, the most vexing problem will be the headroom – just 5′ 4″ in the saloon, unless you stand in the open companionway hatch under the dodger. The lack of headroom isn’t an acute problem for everyone, since virtually everything belowdecks is done sitting, lying down, or bending over. The low overhead would, however, become tedious if you were cooped up for several days on board in rainy weather.

Performance

Now the fun part. The J/105 is fast and handles like a sports car. Indeed, sprit boats like the 105 created the so-called “sport boat” genre.

Powering the 105 is a tall, keel-stepped, tapered fractional-rig mast with double airfoil spreaders. Mast and boom are painted with Awlgrip polyurethane. All stays are Navtec rod. Shrouds are continuous, meaning they are a single piece; this avoids potential problems at extra terminal fittings, such as at spreaders, but requires careful bending of the guide tubes at the spreader tips. Continuous or discontinuous, rod rigging saves weight aloft and reduces windage.

On early boats, the balsa core in the deck was not removed in the area where chainplates pass through. Because chainplates work on any boat, it’s nearly impossible to keep that interface watertight. As a result, some cores got waterlogged. On later boats, the core was removed in favor of solid glass. Then, the little bit of water that migrates down the chain plate causes no harm – unless it enters bolt holes drilled in plywood bulkheads. So, bulkheads should be checked, too.

Hardware includes a Harken furler for the jib, Lewmar 44AST 2-speed primary winches, Lewmar 30AST 2-speed halyard and secondary winches, Schaefer turning blocks, Spinlock rope clutches, Harken traveler and mainsheet systems, carbon fiber sprit with under-deck launching and retraction system, Sailtech backstay adjuster, and Hall Quick Vang. This is all top quality gear; Practical Sailor has long rated the expensive Quick Vang as the best rigid vang made.

The asymmetrical spinnaker is in a snuffer, so that jibing can be a one-person operation. The spinnaker can be partially reefed.

A number of owners have mentioned water entering the boat through the sprit tube in the forward cabin, inspiring a number of creative solutions involving neoprene rubber and various lip seals.

When Doug Logan test sailed an early J/105 10 years ago off Miami, conditions were ideal for showcasing the boat’s strengths – a 20-knot northeasterly and three-foot waves. “For the better part of an hour we maintained speeds between 12.5 and 13.5 knots, never lower than 12 and up to 14.8 at the top end. This wasn’t a stomach-churning reach either. We had excellent control of the boat, and didn’t have to work hard.”

On the way back upwind, the boat was overpowered due to the lack of a reefing line. “Even so, we made 7.5 knots with the sheets just slightly eased.”

(The full Sailing World review is on the J/105 page at the J-Boats website, www.jboats.com, under “Less Is More.”)

Owners say you can sail with full main and jib up to about 22-25 knots, after which they switch down to a storm jib, and at around 30 knots put a reef in the mainsail.

A class controversy involves adjustable genoa sheet leads. Class racing rules prohibit the use of block and tackle and bungy cord to move the car from the cockpit. Instead, a crewmember has to go on deck and manually move the car. If there’s a load on the car, rather than easing the sheet (and losing speed) some people try stepping on the sheet forward of the car so that it can be moved. This, say proponents of adjustable leads, is dangerous. Opponents say adjustable lead systems are expensive and unnecessary. Some owners have installed adjustable systems for general-purpose use, but have pins installed in the cars for use when racing.

The auxiliary is a Yanmar 2GM20F diesel, which means two cylinders, 20-horsepower, freshwater cooled. A number of owners note that it jumps around a fair amount on its soft mounts, which in some installations has made dripless shaft seals leak. For those owners, a better alternative might be one of the dripless packing materials, such as Drip Free, in a conventional packing gland.

Conclusion

By all measures, the J/105 has been, and continues to be, a considerable success. The reasons are simple: It’s a simple boat that’s fast and fun to sail.

Several decades ago we judged quality by weight: the heavier the boat, the better the quality and the higher the cost. High-tech composite construction has turned that axiom inside-out. Now you pay more for less, so to speak: epoxy and vinylester resins cost more than polyester; modern directional and high-strength fabrics and fibers cost more than chopped strand mat and woven roving; and vacuum bagging and infused resin molding methods like SCRIMP cost more than chopper gun spray jobs and hand lay-ups. Further, the tapered spars used on J-Boats cost more than the telephone poles found on most boats. Then there’s the carbon fiber sprit, rigid boom vang, and other stuff that’s not part of your standard cruising boat package. All this is to try to explain the average out-the-door price of a new J/105 of about $150,000. Prices of recent-year used boats range from $85,000 to $130,000 depending on equipment and condition. Deals are better on older boats (see the price history on a 1992 model above). Bear in mind that most J/105s will have been sailed flat-out. They don’t seem to sit around the yard much.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Used Boat Price History: J/105 – 1992 Model.”

Contact – J-Boats, 401/846-8410, www.jboats.com.