New Zealand may be a small island nation on the far side of the world, but that little nation is having an impact on the US marine industry all out of proportion to its size. At the recent Ft. Lauderdale boat show, New Zealand-built yachts won four major superyacht awards for excellence in construction. In 2001, the value of New Zealand marine industry exports was about $175 million US. In the last five years, exports have increased in value about 23% per year, at a time when large parts of the US marine industry have been relatively stagnant.

What’s driving the growth in this industry, and is there anything the average US sailor can do to benefit from it? There are two major factors behind the growth spurt of New Zealand’s marine industry: the existence of a large class of trained marine tradesmen, and the relative weakness of the New Zealand dollar compared to other currencies, including the US dollar. New Zealand has always placed emphasis on the development of a skilled class of tradesmen, including the marine trades. Unlike the US, which tends to stratify the culture into those with college degrees and those without, a relatively small percentage of New Zealanders attend college. What we would term “blue collar” trades have far higher standing in New Zealand than in the US.

Unlike the US, New Zealand has a government-supported formal apprenticeship program for the marine trades. New Zealand’s Boating Industry Training Organization writes the qualifications and administers the training, which is partly underwritten by the government.

In 2002, there were 500 registered marine trades apprentices, with 90 percent of those apprentices employed by New Zealand boatbuilders. Apprentices represent about 10 percent of the total employment in boatbuilding, and provide the foundation for future growth in the industry.

In the US, relatively few people see boatbuilding as a long-term career choice. In New Zealand, boatbuilding is a trade at least on a par with any other, and marine tradesmen have a productivity that compares favorably with that of any developed country.

The New Zealand Dollar

There is no doubt that the weakness of the New Zealand dollar relative to the US dollar is a big plus for New Zealand’s marine industry. With much of Europe adopting the Euro as the standard currency, the price of labor and materials throughout the European continent has begun to level out. The cost of labor in traditional yacht-building countries like Holland and Germany is now actually higher than comparable labor rates in the US.

Depending on who you talk to, this higher European labor cost may be partially offset by a slightly higher level of productivity in the European marine labor market, but we’re splitting hairs here.

New Zealand’s dollar floats in its own world, without direct ties to any foreign currency except those created by market forces, including interest rates. Over the last three years, the New Zealand dollar has fluctuated from a high of about $.54 US to a low of about $.40 US. This should have a pretty dramatic impact on the price of New Zealand-manufactured goods once they reach the US market. In practice, however, prices in the US won’t reflect short-term fluctuations in the value of the New Zealand dollar.

Where fluctuations in currency will have an impact is on the construction of new boats in New Zealand. At this time, custom boatbuilding sheds throughout New Zealand are full of projects for European and American customers, and here’s why: Generally, the costs of custom boat construction are pretty evenly divided: half for labor, half for materials. New Zealand produces few of the materials actually used in boat construction. Steel, aluminum, wood, fiberglass, and resins all are imported. Engines come from Japan, the US, or Europe. Electronics come primarily from the US or Japan. What New Zealand provides is the skilled labor to turn the raw materials and overseas-sourced components into a finished product.

Suppose you’re building a 50′ custom sailboat that would cost $1 million in the US. (Don’t you wish!) Let’s say there are 15,000 hours of labor in that boat, at an average cost of $33 per hour. You’ve spent $495,000 on labor, pretty much half your budget. All other things being equal, suppose you could reduce that labor cost to $20 per hour. At that rate, you’ve knocked $195,000 off the cost of building the boat.

Of course, all other things are never equal. Some of the material costs in the US are substantially lower than they are in New Zealand, and some are more. It costs more to ship a Caterpillar engine from Illinois to Auckland than to ship it from Illinois to Rhode Island.

When the boat is finished, you will have to ship it back to the US and pay the duty when it arrives, unless you plan to sail it home. If you build a boat overseas and can’t be on-site all the time, you may be faced with hiring a full-time project manager. Your travel costs to visit the boat while it’s under construction will also be higher. On your million-dollar boat, you’ll be lucky to end up saving 10 percent on the project when all is said and done.

But let’s up the ante. Suppose instead of a million-dollar 50-footer, you’re building a $10 million dollar 120-footer. Your labor savings alone could amount to almost $2 million, compared to building the boat in the US or Holland.

The larger the project, the smaller the management costs become, proportionally. It costs the same to fly to New Zealand to look at your 50-footer under construction as it does to view your 120-footer.

The Megayacht Boom

This explains in part why the megayacht construction industry is booming in New Zealand. In a country that lacks a large production fiberglass boatbuilder such as Catalina or Beneteau, there are at least 20 megayachts – 90 feet or more – under construction today, and the boats are getting bigger all the time. Facilities are now available to build boats under cover up to about 200 feet in length.

There is also a rapidly growing megayacht refit industry in New Zealand. Yachts in transit are exempt from local goods and services tax (sales tax). In addition, the New Zealand government has recently exempted the wages of transient yacht crews from local income taxes, which had previously been an issue for yachts overstaying the six-month grace period, after which their wages became taxable during a major refit.

Rapid government response to an issue such as this is only practical in a small country such as New Zealand. Imagine trying to push a bill through the US Congress to eliminate someone’s liability for income tax!

The Small Stuff

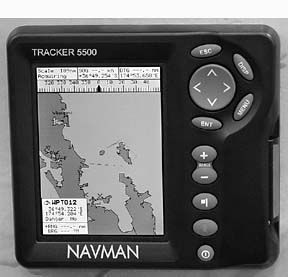

Right now, labor-intensive marine products and services constitute the bulk of New Zealand’s marine exports. Along with sailmaking, spar building, and boatbuilding, however, there’s a growing ancillary industry in electrical products, marine electronics, marine software, and hardware. (Note the sidebar on Cruz-Pro’s PC-Based Fishfinder/Sounder in the December 2002 issue.) We’ll take a closer look at these New Zealand industries in the coming months.

The Balancing Act

Despite the pool of skilled marine trades labor and government’s support for training programs, the demand for that labor is growing faster than the rate at which skilled labor becomes available. That, in turn, exerts upwards pressure on the cost of labor. If the value of the New Zealand dollar continues to rise – it has increased 15 percent against the US dollar in the last nine months – the growth curve in the marine industry will tend to flatten. The unique combination of factors which has contributed to rapid growth can just as quickly disappear.

Marine goods and services are almost always paid for with discretionary spending. You don’t need a boat to live – well, most of us don’t – and your 10-year-old sails might just survive for another season. If it comes to the choice between a roof over your head or a boat on the mooring, most of us would opt for the roof over our head. Continued slow growth or negative growth in the economies of the world will inevitably impact even expanding sectors like as New Zealand’s marine industry.

For the New Zealand marine industry, the key to long-term growth is a stable and undervalued currency, expansion of the skilled labor pool, and the perception of good value per dollar spent by the customer.

When Calypso underwent her big refit in New Zealand three years ago, we got excellent value for our money. There’s no way we would have undertaken most of the work we had done if we were back in the US. Our sails cost half what they would have in the US, since sailmaking is a labor-intensive task. Our engine overhaul was about two-thirds the cost of the same job in the US, since parts were a significant part of the cost of that job. Canvas work and painting were about half the US price, and dock space was even less. For cruising sailors on their way across the Pacific, New Zealand is an obvious stop.

The realities of the marine distribution system mean that most New Zealand-manufactured marine products will not be significantly less expensive than their domestic or European counterparts by the time they reach the shelves of a chandlery near you. What you may find in some cases, however, is a step up in quality for the same dollars. That’s still a pretty good deal when it comes to owning and maintaining a boat.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “High-Quality Anchor Winches from Maxwell.”