For some time, it has been our view that, as a stand-in for a standard 10-inch steel I-beam 50 feet long and weighing 1,720 pounds, there will be, sooner than you think, a piece of rigid foamed plastic that you can pick up with one hand. And the plastic beam will never corrode or fatigue – which means that you could pair it with glass (the world’s other wonder material) and build something to last forever.

A bellwether for this world-of-tomorrow view is rope, which has progressed rapidly from manila to nylon to Dacron and now to some of the most amazing stuff ever conjured up.

Rope using Kevlar has been used for some time now, especially for running backstays, to which custom metal terminals are fitted. As things have progressed, PS has presented quite a bit of material about UHMW-PEs (ultra high molecular weight polyethylenes), as the new chemically engineered ropes are designated.

It sets our jaw agape that Yale Cordage is making a new line out of Zylon that, in the 1/8″ size, has a breaking strength of 5,000 pounds. (The newest “hot line” is made in Italy by Gottifredi Maffioli; a name like that is bound to acquire “glitz” with the racing clan. Maffioli makes Dyneema single and double braid in 6-14 mm and a small boat line, 3-9 mm, called Swiftcord, with a fuzzy cover.)

These high-tech ropes are bald-facedly challenging steel wire in virtually every application – not only for boats but in architecture, industry, utilities, and telecommunications. “I’ve got a rope for every wire ever made,” said one rope manufacturer. The potential usage of these modern ropes has everyone scrambling.

In the September 2001 issue, PS published a market scan on what was available (at that time), using basic fibers called Vectran, Kevlar, Twaron, Technora, Spectra, Dyneema, and Zylon. A chart explained their properties and who owns each.

In the same issue was a bench test report on how well conventional knots and splices hold in the slippery lines made with these fibers (not well) and, more importantly, how much of their breaking strength is surrendered when the line is knotted. It was a shock: High-tech line loses much of its strength – 50% is common – when knotted. Sure, there’s usually plenty of strength left, but we felt then, and still feel, that high-tech line is not well-suited to roles in which it needs to be quickly knotted and trusted to stay put. When knotted, it should be set tightly by hand and finished with an extra hitch or two. We found that buntline hitches were quite reliable, since they lock and put pressure on the bitter end.

High-tech line, on the other hand, seems extremely well-suited to applications like halyards, running backstays, and (as we’ve been discussing in recent issues) lifelines – where it can be terminated by a splice or a custom metal or composite fitting. And, as we’ll see, high-tech line is beginning to replace metal fittings themselves.

Metal-to-Rope Terminals

There are a number of companies and individuals working on ways to capitalize on the almost unbelievable strength of these new fibers. Again, the emphasis is on not only running rigging, but standing rigging, too.

The goal is to replace wire, rod, and metal fittings with much lighter line. It’s mostly to save weight aloft, which is vital on a racing boat but is also of concern on any boat. Unless it’s a keel, wrecking ball, or offensive tackle, any engineer will take “light and strong” over “heavy and strong.”

For the moment, let’s talk about end fittings – shackles, turnbuckles, toggles, etc. We checked with a couple of terminal-makers familiar to sailors around the world – Norseman and Sta-Lok – to see if they were yet fabricating metal or composite swageless terminals to be used with UHMWP line made with Spectra, Dyneema or Zylon.

“We have done some work with synthetic rope,” said Terence Barfield, Sta-Lok’s managing director, “We have developed prototypes. However, we have not finalized designs.”

Ty Goss of Navtec, the leading maker of rod rigging, and also maker of Norseman terminals, says that the company has been concentrating on higher-end, higher-load PBO and carbon products, largely for the America’s Cup, but that they’ve also been working on terminals for UHMWP line. “We’re of the philosophy that if someone’s going to obsolete rod rigging, it might as well be us,” says Goss. As for terminals that can be afforded, fitted easily, and trusted by the cruising community, Goss says, “We’re still very much in the development stage. We’ve been able to design fittings that will take a breaking load test, but we haven’t gotten to the Navtec standard for fatigue life.” Knowing Navtec, we have no doubt that it will happen.

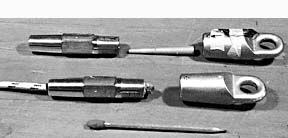

An old-line company called Esmet, Inc., in Canton, Ohio, has for years made wire cable terminals for military, industrial, and heavy construction applications. Esmet’s terminals, which resemble Sta-Lok and Norseman fittings, are now offered for some synthetic line. However, the fittings are huge.

Esmet’s chief engineer, Bob Shaw, said that because synthetic line is so slippery, the internal, gripping cone used in these fitting must be long, which makes the fittings cumbersome. Even then, the ends of the fibers must be both seized and fused to further discourage the slippery fibers from creeping.

Rope and hardware manufacturers, stimulated by creative riggers, currently are having a determined run at metal shackles. There are a lot of shackles on boats. (This is PS’s second recent report on shackles; see last month’s issue for a market scan on metal shackles.)

Ti-Lites – and the Like

It might be said that the movement to make stainless steel shackles obsolete was started by Harken, the ever-innovative Wisconsin company. Seeking lightness (because it caters to those who seriously race boats), Harken started offering webbing attachments for its blocks some time ago. Webbing is, by any measure, much stronger than conventional Dacron rope.

The strength of the new UHMW-PE line (it’s stronger than Dacron webbing) stimulated Harken to bring out, in 1999, a line of versatile blocks called Ti-Lites – which utilize a lacing of three turns of 1/8″ Spectra. The line is Yale’s “Pulse,” which has a Spectra fiber core and a Dacron cover . In the 1/8″ size it has a breaking strength of 800 pounds. With a six-part lacing, the strength of the “shackle” jumps to 2,380 pounds. Because the lashing eliminates not only the shackle but also the head post and swivel, the weight savings is impressive – 3.1 oz. for the conventional block vs. 2.4 oz. for the Ti-Lite. In any endeavor, a weight saving of that magnitude (without sacrificing strength) is big news.

The next development was already in the works. It doesn’t matter much who came first with the idea of using just a loop (or ring) of UHMW-PE line in lieu of a stainless shackle. In essence, they’re not much different than old-fashioned manila grommets, which were often used as strops.

Yale Loups

Yale Cordage in Biddeford, Maine, announced last January that it was bringing to the marketplace a device to replace a metal shackle. Called a Yale “Loup,” its basic purpose is to reduce weight. On one racing boat, Team Adventure, which sailed in The Race, 30 Yale Loups replaced metal shackles and attachment points, with a weight saving of more than 200 pounds.

“After the race,” said Yale vice president Dick Hildebrand, “some of the Loups tested better than when they left the factory. They don’t look like they’ve been around the world.”

The Loup was a joint creation of Yale CEO Tom Yale and the extremely competent rigger Brian Fisher, of Aramid Rigging in Portsmouth, R.I.

Fisher said he and Yale spent eight months developing the product, which is basically a ring of Dyneema with a Spectra cover. He good-naturedly declined to say how the ends of the Dyneema are joined.

“Secret,” he smiled.

(Naturally, Aramid is the sole licensed manufacturer of the Loup.)

Fisher explained that to add about 15% to 20% more strength, the Loup is annealed, meaning that the ring is pulled under a heavy load and hit with live steam.

Depending on how it’s rigged, the safe working load of the Yale Loup, which is made of 9 mm to 21 mm line in stretched-out lengths from 4″ to 24″, ranges from 3,604 to 44,100 pounds. Yet they weigh from a half ounce to 4 ounces, about a third of the weight of stainless shackles of equivalent strengths… and that doesn’t count the weight saving from eliminating the posts on the blocks.

The Yale Loup is, of course, a closed ring. To affix one to a block, the block must be dismantled. For padeyes and other applications, the Loups must to made in place.

The rigging variety has given rise to some new terms. A Loup can be rigged vertically (just stretched out), as a “basket” (doubled), as a “choker” (looped back on itself), or “boned,” which means with a pin. The photo and caption above might make that clearer.

Yale Loups, simple but labor intensive, range in price from about $25 for a little half-ounce 9 mm version, 4″ long, with a basket safe working load of 7,208 pounds, to $45 for a 21 mm, 10″ long model with a basket SWL of 44,100 pounds. Pretty stunning, no?

EquipLite Shackles

On the other side of this little sphere on whose surface we swarm, a professional engineer named Don Curchod was noodling. After spending 25 years working in the United States, Curchod had returned to Sydney, Australia, for his retirement years.

Unable to tolerate idleness, he got thinking about using what he calls the “super braids” to “overcome the weight and cost problems in metal boat hardware.” After a year or two of prototypes, he came up with what he now calls “EquipLites,” which, until you see one, is difficult to explain.

Let’s try: An EquipLite is a loop of exotic line with the ends cold-fused, one end of which is inserted and secured in an aluminum double-spool (or bobbin, as Curchod calls it), one groove of which engages the other end of the loop, with the other groove for splicing to a halyard, sheet, etc. Right?

Curchod said he tried “to no avail” to interest Lewmar, Harken, and Ronstan in his idea. So he formed his own company, filed for a patent, and hit the market about a year ago. He now has five employees and has sold “well over a thousand” EquipLites, which, while substituting for shackles, swivels, and deck loops can give weight savings of 65 to 90 percent. He also attracted a very prestigious U.S. distributor – Hall Spars & Rigging in Bristol, R. I.

Although priced at near the cost of equivalent stainless hardware, EquipLites are not cheap. They go for $65 for a small one (.2 ounces) with a breaking strength of 5,000 pounds, and $279 for a biggie (5.6 ounces) that’ll take 55,000 pounds.

Curchod makes other versions, including a two-block arrangement, a swivel version, etc.

As an innovator, Curchod has had some developmental problems. When it was explained that a maker of conventional shackles had told PS that the flanges on EquipLites tend to bend out of shape, a Hall Spars spokesman nodded affirmatively. No doubt, this is being ironed out as we type.

At this point, the plot thickens. Aramid Rigging has a device that is almost an exact duplicate. Aramid calls it a “LoopIt” – a ring of Dyneema with a Spectra sleeve and an aluminum spool with two grooves. So far the LoopIt comes in but one size – a 20,000-pounder for about $100.

Brian Fisher said that Aramid had the same problem with the LoopIt spool flange bending as Curchod and Hall had with the EquipLite, but solved the problem by beefing up the flange and using a superior grade of aluminum. Further, to avoid the problems experienced by Curchod in securing the fixed end of the loop in the hole in the spool (he tried gluing and an enlarged socket seat), Fisher said Aramid went directly to a cylindrical metal pin in the spool.

Although a piece of hook-and-loop tape comes attached to each EquipLite to make sure the loop doesn’t inadvertently fly open, there’s no such need with a LoopIt, whose grooves are deeper.

These weight-saving gadgets are fast popping up on big racing boats. If you watch the America’s Cup coverage on cable television, you’ll occasionally catch a glimpse of one.

They’re a bit strange to look at, but eminently utilitarian. Price aside (and they should come down in time), it’s the light weight that is alluring. Almost as sure as the rising sun, they’ll soon appear on chandlery shelves and on stock cruising boats. And they are further testaments to the eventual fate of steel I-beams, H-beams, girders, trusses…

Also With This Article

Click here to view “An Explosion Called UHMW-PE.”

Click here to view “Long-Lived Line?”

Contacts-Aramid Rigging, 401/683-6966, www.aramidrigging.com.

EquipLite, 02 9974 6645, www.equiplite.com.

Esmet, 800/321-0870, www.esmet.com.

Hall Spars, 401/253-4858, www.hallspars.com.

Harken, 262/691-3320, www.harken.com.

Navtec, 203/453-9878, www.navtecnorsemangibb.co.uk.

Sta-Lok, 800/458-1074, www.stalok.com.

Yale, 207/282-3396, www.yalecordage.com.