When you create a boat that’s universally celebrated as “the most successful production raceboat ever,” what do you do for an encore? In 1966 the Cal 40 capped a famous string of grand prix victories when Thunderbird (with designer Bill Lapworth and America’s Cup helmsman Bus Mosbacher aboard) won the Newport-Bermuda Race while sister ships placed 1-3-4-5-6 in Class D. Coming as it did after three successive TransPac victories and an SORC title, the performance confirmed the 40-footer as the hottest thing around, inspired a “Stamp out Cal 40s” movement, and offered an off-the-shelf way to win in a league where only custom designs had been able to play.

For designer Lapworth and builder Jack Jensen there followed an “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” string of racer/cruisers built on Cal 40 principles. Some of Jensen Marine’s many boats (at least 20 models over the years) have been full-cruising “performance motorsailers” like the Cal 46, but the vast majority were racer/cruisers. Virtually all of those were descended very directly from the boat that fueled the company’s success, the famous Cal 40.

By 1979, when Lapworth and Jensen collaborated (for what turned out to be their final time) on the Cal 35 , the world where once the Cal 40 ruled had changed. The International Offshore Rule (IOR) was no longer the only game in town, spars were spindlier, fins were more blade-like, and racing boats had changed a lot. Sunroofs, swim decks, hull ports, anchor pulpits, and cockpit tables had also, in the meantime, arrived to add new dimensions to cruising. The ideal of a “dual-purpose” boat for racing and cruising was still alive, but the forces driving racers and cruisers apart may never have been so strong.

You only need to read the first sentence of the press release announcing the Cal 35’s debut to see that Jensen Marine saw its new 35 as a balanced, conservative response to those forces of upheaval: “She is quite ‘establishment’ in her attitude toward rewarding sailing but quite ‘individualistic’ in her solution to offshore and dockside accommodations.”

In creating the 35, Jensen Marine stuck with the formula that served it well from the Cal 40 forward: “moderately light displacement, waterlines on the longish side, fin keel, and high-efficiency rudder.” To suit the boat to the times, the publicist adds, “In all candor, however, the new Cal 35 is weighted toward high-performance cruising—real sailors’ cruising.”

While she never won much as a racer, she succeeded in fulfilling that “fast-cruising” formula. That is what has kept her alive on the used-boat market, and why sailors might do worse than to look at her as a couple’s cruiser.

“You can’t please everyone.” Almost 100 Cal 35s were built in the early ’80s, however, and as a designer friend of ours says, “Those stodgy traditional looks seem to get better and better the more time goes by.” She’s well-built, sails well, and seems in many ways to justify the premium price that’s attached to the Cal name.

“I sailed the hell out of mine for 18 years and I’ve never had a boat that I loved more,” one owner told us.

Design

Nathanael Herreshoff was among the first to design a spade rudder, but offshore racers didn’t get to steer with them until Lapworth came forward with the Cal 40. We can remember the “night and day” experience of our first trick at the tiller of one of the Jensen Marine boats. The helm combined sensitivity and control in amounts that were astounding. “The spade” made keel-hung rudders seem as outmoded as cotton sails. We couldn’t help but notice, however, that the balance on those early rudders was overlarge—under power they seemed to exercise a mind of their own; keeping the boat tracking with the engine pushing her took full-time concentration.

Lapworth has no patent on the other signature element of the Cal 40—the fin keel. But, married with the balanced spade, it cut underbodies loose from long-keel bondage and opened the way for lift-producing foils and struts to follow. It made surfing a way of life, and opened up the offshore world to dinghy-like standards of performance and speed.

The underwater elements of the Cal 35, however, don’t show much advancement beyond the pioneering Cal 40 underbody. While European and American naval architects of the late ’70s and early ’80s shaved wetted surface and made their foils higher aspect (thus more efficient at producing lift) the Cal 35 took a middle route, somewhat in keeping with the boat’s “please everybody” mission, with a conservatively thick section, long chord length, and low aspect-ratio planform. She thus has plenty of get-up when the wind is free and strong but is at her worst upwind in light air and/or chop.

Lapworth always championed light boats. Some West Coast featherweights may have been more extreme, but his “get the lead out” efforts were another big reason why his Cals were so hard to beat. The Cal 35, however, displaces just 2,000 pounds less than the Cal 40. Comparing sail area/displacement numbers shows that the newer, smaller boat looks better on the calculator (18.2 versus the Cal 40’s 17.7) but in a racing world where spade rudders and fin keels are old hat, and where the push for speed potential is constant, such a small gain seems very little to show for 20 years’ worth of design development.

Lapworth did concentrate on finer bows with his later designs. The entry on the 35 (and the designs that directly preceded her) was sharpened materially “to help the boat in slop and chop.” The clean sweep of the waterlines, and the flat deadrise aft, make her surf relatively easily, but when you compare her to the virtual planing shapes of her dishier modern competitors, it’s a case of obsolescence at best.

The 35 has a ballast/displacement ratio of 40%. That is robust, but modern racers push that stability-producing number higher. The J/35, for instance, carries a figure of 45%. Despite carrying a lot of lead, the Cal 35, like all the Cal boats, has it encapsulated in a resin matrix within a fiberglass keel. That effectively reduces the density of the fin and accounts in good measure for her performance review as “somewhat tender.”

Another reason why she has to reef before her competitors is that her hull shape, although clean and surf-ready, is a bit narrower and has softer chines than the majority of the boats that came after her.

Cals were never beauty queens. Their aesthetic has a lot to do with function. The short-ended, lean and mean look of the Cal 40 derived much of its appeal from her place in the winners’ circle. The Cal 35 is cut from the same cloth, but, because of her emphasis on the cruising side of the ideal, she has softer, prettier styling than her ruthless forebear.

Her sheer is straight without being knife-edge, her stem is elongated and more delicate than the 40’s, she has almost no counter, and her transom is delicately reversed. The house is broken out into big windows and little ports. Dorade boxes on either side of the companionway form part of her look. She’s as middle-of-the-road in appearance as she was meant to be in function.

Construction

When Jack Jensen, a mechanical engineer with little or no background in boats, established Jensen Marine and started building Lapworth designs in 1958, there weren’t many other production builders around. His thought, it’s been written, was “that production-line construction of small fiberglass auxiliaries would work.” Starting with the Cal 24 (an immediate success) and the Cal 20 (over 1,700 sold) he and Lapworth confirmed that wisdom.

Early in the company’s evolution Jensen developed some of the basics that remained his hallmarks. Rather than use a fiberglass pan as a structural grid or locater for interior furniture, Cal built the entire interior outside the hull. There were some efficiencies with the technique, but the prime virtue was that (once the wooden framework was dropped into place) it allowed access all around the interior so that it could be taped to the hull in a number of different places rather than being left to “float” as it would be in the areas beneath a pan. This building method exposes a significantly greater amount of wood in the bilge, but high-quality plywood and careful taping have kept rot problems to a minimum.

The 35’s hull is solid glass. A sailor who bought his Cal 35 in 1980 wrote: “Mine was one of the very last boats laid up in Costa Mesa. I’ve heard that the boats built later in Tampa had blistering (and some other problems). I’d advise anyone looking at Cals built after 1982 (when the move to Tampa occurred) to check this out.”

Moderate blistering was reported by a handful of owners from our survey.

The deck is plywood cored. Said one owner of a 1983 boat, “The only problem I’ve had was having to take up a 12-square-foot section of deck and replace the plywood coring.” A number of others however, report gelcoat crazing at corners and stress points.

Cal decks have been joined to the hull in several ways, but the method evolved with the 35 has earned several owner reports that they’ve had no leaks through season after season. The hull is built with an inward-turning flange. The deck, built with a down-turning flange, is dropped over the hull and the joint is bedded with sealant. The edge is then capped with a perforated aluminum toerail that is bolted both horizontally and vertically to anchor the joint. No one came forward to report deck leaks, though some owners have had their boats for 20 years or more.

One Long Island owner wrote that, “My boat took on major water due to the design of her anchor locker drains, as well as the mounting for the cutless bearing strut.” He concluded that his Cal 35 was “a beautiful sailing boat that was rather poorly built.” That owner’s report, however, seems to be an aberration. We’ve received testimony from a good number of owners who confirm that the “well-built” reputation Cals have earned over the years is well-deserved.

Accommodations

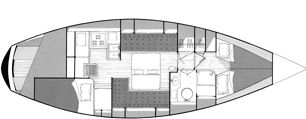

Though brochures called the Cal 35 “what may be the most thoroughly thought-out performance cruising yacht ever offered the sailing world,” there isn’t much below that you haven’t seen before. Part of the thinking, in fact, was to redesign her interior after only 50 boats were sold in the first three years of production—a molasses-like pace for Cal at the time. The boat originally had a head aft and galley opposite. “I have the original layout,” says one owner from 1981. “I still think it makes an excellent couples boat. Who needs all of those bunks anyway?”

The “Mark II” version is more standard. The 6’4″ headroom hasn’t changed, but the floorplan has. The Mark II setup offers a quarter berth aft, two settee berths in the saloon, and a substantial platform double in the forepeak. The arrangement showcases a truly well-designed head/shower with maximum elbow room, light, and ventilation. It is sited in the “traditional” spot forward of the saloon. Double sinks on the centerline are another good addition.

There’s a distinctively traditional handling of teak and holly in the sole through teak accents, as well as teak cabinet fronts, ceiling panels, and bunk bases. One owner told us, “The 35 isn’t a boat you’d buy for the furniture—they did cut some corners here and there below.”

As is typical in galleys on boats this size, the bottom of the icebox is hardly accessible if you’re not six feet tall. And, complained one owner of a boat new in 1980, “the icebox is large but not well-insulated.” A second agreed. Though access was a critical problem, he removed the foam battens from around the box and foamed the entire cavity. “I’m very happy with the upgrade,” he said.

The drop-leaf table in the saloon is a big improvement over the clumsy mast-mounted table that it replaces. The electronics storage seems very minimal when measured by modern standards. Ventilation is better than average thanks to the well-sited (for air, not sail-handling) Dorade vents, six opening ports, and opening overhead hatch. The standard hatch in the forepeak, however, leaks. Stowage includes a pleasing number of drawers.

Performance

One place where the 35’s clean lines, long waterline, and moderate displacement really shine is under power. The standard Universal 32-hp four-cylinder diesel consistently pushes her past her 7-knot hull speed and consumption at cruising speed is less than a gallon per hour. “I have a Martec prop,” one owner says. “I like it for sailing, but it sometimes doesn’t open fully when I change gears.”

Several owners rated noise and vibration as “very smooth and quiet.” Some also felt that the Cal 35 “walked” excessively (backed to port) in reverse. “But the big spade rudder and smallish fin give her a very small turning circle.”

If you take the Cal 35 onto most race courses you won’t be as dominant as the early Cal 40s. For one thing, 13,000 pounds hardly qualifies as even “moderately light” these days. In the world of drop-keeled rockets and winged speed merchants you might call something like a J/105 (just 6 inches shorter than the Cal 35) “moderately light.” Weighing in at 7,750 pounds, that modern J has a displacement/length ratio of 135. (The lower the number, the lighter the boat.) Compare that to the Cal 35’s D/L of 242 and you can see how much the whole concept of light displacement has changed.

One Chesapeake sailor who calls his boat an excellent cruiser/racer said, “I have tried to turn her into a racer/cruiser under PHRF. It worked for two to three years, but after the measurers lowered my rating and new lightweight boats came into the area, I don’t feel that I can continue to compete. I’m going to try IMS next season, add a full-battened mainsail, and install a Hall Quik Vang to keep the sail from getting chewed up by the topping lift.”

While there is variation from fleet to fleet, the Cal 35 rates around 160 under PHRF. Neither a “sleeper” like some re-vamped ’80s boats, nor a rocket like the original 40, capable of running away from her competitors no matter what the rating, the Cal 35’s racing success has been middling at best. However, in terms of efficient, mannerly, seakindly sailing of the sort that makes for superlative cruising, this old boat delivers the goods. While her relatively bluff bow puts her at a disadvantage in light air with waves, her full entry helps the boat ride high and dry, especially while surfing down waves. Flat sections forward of the keel can cause pounding, but they are also a key to the boat’s crisp and surprisingly fluid motion. Chopped off at the transom she maxes out her waterline; high-sided forward she is dry on deck.

Though her mainsail is, in the fashion of the ’80s, smaller than her foretriangle, it is large enough to make main- alone sailing not only possible but pleasurable.

Like the Cals before her, the 35 has inboard shrouds to facilitate tight sheeting angles as well as let people walk the side decks with ease.

Several owners felt the need to relocate the pedestal 4 inches forward and install a 36-inch wheel in place of the standard 28-incher. “The Barient 25s that came with the boat were too small,” said a sailor from the Great Lakes. “I took them off and installed 28s.”

The mainsheet arrangement called for a number of parts and what amounted to two travelers, one on the housetop and the other on a horse over the companionway. Several sailors found the set-up “poorly designed” and over-complicated.

Conclusions

Whoever wrote the brochure back in 1980 had it right—the Cal 35 is more of a cruiser than a racer. It’s impossible, though, to dissociate the Cal name from the fin-keeled surfing machine that grabbed all of the headlines back in the ’60s.

The good things about buying into a racing family seem to us to include the satisfaction that your boat is, in at least one sense, pedigreed for performance. There comes an association with people who are at the top of the sport, and no company exemplifies the halcyon days of the racer/cruiser (or cruiser/racer, whichever you prefer) than Cal.

Among the shortcomings of this set-up are the possibility that you’re paying for reputation and prestige instead of solid value; that the people at the top are so worried about staying there that they have little time for their customers, and that competitive excellence can sometimes provide a screen that hides corners that have been cut. We don’t think this is true in any serious way about the Cal 35. She’s a solid chip off the Cal block.

At press time, Internet asking prices for used Cal 35s average around $43,000, not including one 1985 Mark II boat offered in what appears to be pristine condition at $70,000.

After changing hands several times, Cal finally folded in 1989. For more on the Cal 35 and Cal boats in general, try joining the Cal owners’ e-mail discussion list at www.sailnet.com.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Owners’ Comments.”

Excellent and informative. buying a boat ,trying to decide between a 1984 cal 35 Mk11 or a 1984 endeavor 33 sloop “Any advice”