For us, waypoints exist in time as well as space. Waypoints are three-dimensional: latitude, longitude, date and time. With Calypso going to new owners, it’s a good time to revisit some of those waypoints.

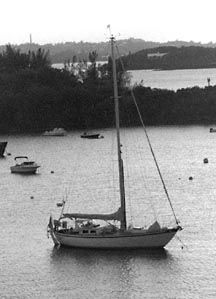

Waypoint: Town Cut, Bermuda

32° 22.7N, 64° 39.7W

November, 1997

At dusk, Bermuda is just appearing on the horizon, a small hazy blob with lights twinkling faintly through the humid haze. We have been hard on the wind for three of the last five days, in winds of 30 to 40 knots. It has been difficult sailing under double-reefed main and staysail, and we have been hand-steering for the last 24 hours after the safety tube on the wind vane snapped when a big wave caught us broadside on.

Maryann has been sick and depressed for much of the trip, and I don’t blame her. Is this what our cruising life will be like, perpetually going to windward, cold, wet, even scared? This is not the way to start a circumnavigation.

In the last few hours the wind has veered slightly, and we are able to lay the fairway buoy just outside the reefs. As Calypso slides under the lee of the Mills Reef, the seas flatten somewhat, and the winds ease to 25 knots.

It is dark now, and the lights of Bermuda dot the horizon in a familiar pattern. I have made this approach more than 20 times, over half of them during darkness, but never as skipper of my own boat, the solid product of imagination, longing, and interminable work.

Racing, I have shaved these reefs so close that the bottom loomed ominously clear below the keel, anything to save a few seconds. Cruising, I give them a wide berth, but my mouth is still dry.

We enter The Narrows, the only clear route through the reef, and spot the lights in Town Cut. The channel seems impossibly narrow through the looming limestone cliffs, but I have seen big ships go through here, so close to each side you could touch them from the shore.

Halfway through the Cut, the wind drops to less than 15 knots, the sea goes calm. After the howl of the wind for the last few days, the calm is ethereal until shattered by the welcoming cries of a thousand tree frogs. The smell of land—flowers and damp earth—is overwhelming.

A few minutes later, we tie Calypso to the customs dock, with 635 miles down, and 29,000 miles to go.

Waypoint: North breakwater, Panama Canal

9° 23.3 N, 79° 54.9W

January, 1999

After more than a year of cruising, our confidence is growing, but we’re still novices by any standard.

The Panama Canal is one of the great crossroads of the world, and getting here—one way or another—has been a goal since childhood. My father’s stories of his years in Panama come back in a flood, but it is an orderly flood with definable streams.

As we thread our way through the maze of anchored ships waiting their turn through the locks, the dismal twin towns of Colon and Cristobal smudge the horizon to port. It is, I know, one of the most dangerous places in the western hemisphere, where shopkeepers stand casually by their doors with pump shotguns, and cruising sailors are fair game for muggers.

As a young Marine in 1930, my father had walked these streets with his buddies, swaggering and tough. As an Army officer more than a decade later, he cruised Colon with armed guards, by Jeep.

It’s been almost 70 years since my father first came here, but not much has changed. It is still dangerous, still dirty, still vibrantly alive. You are on edge every moment. It is impossible for a gringo to blend in, even a gringo who speaks fluent Spanish.

At this point, we don’t really care. The Pacific lies just 75 miles away, through a man-made ditch that is still a marvel of engineering. Colon is no roadblock to us; it is the gateway to the vast ocean beyond. To reach the Pacific, you must thread your way through the Canal. To reach the Canal, you must endure Colon.

It is here that many cruisers balk, and Panama is littered with the near-hulks of cruising boats whose owners have decided that enough is enough. Unwilling to make the commitment to cross the Pacific, their cruising grinds to a halt. We keep Calypso at anchor, away from the influence of those who have taken root at the Caribbean end of the Path Between the Seas. In a few days, we will head southeast through the Canal, then southwest across the Pacific. It’s the point of no return, and we’re not taking root anywhere.

Waypoint: Jibe to Nuku Hiva

10° 55S, 138° 30W

March, 1999

We have been at sea for three weeks, and this is the middle of nowhere. We reached this waypoint in the middle of the night, and stupidly, I jibed in the dark instead of waiting until dawn.

What a fiasco! Tangled sheets, dazed by a bonk on the head, I sat on the foredeck in the dark, contemplating the follies of the cruising life.

Without realizing it, Maryann and I have both become dangerously fatigued, our judgment questionable. This has been our first really long passage: 3,100 miles, by the great circle route, from the Galapagos to the Marquesas.

We left the Galapagos to horns and cheers from fellow cruisers who were wisely waiting for the northeast trades to fill in. Since then, it has been three weeks of light air, the wind never blowing over 20 knots.

Rolling downwind in the trades may sound idyllic, but the constant motion takes its toll on you. This is our first classic downwind passage, and it is only late in the game that we come to understand how we should have been sailing the boat for the last 3,000 miles. This is definitely a learn-as-you-go circumnavigation.

We are due southeast of the Nuku Hiva in the Marquesas, and the fabled bay of Taiohae. In the 19th Century, American whalers thought this was paradise, with handsome Polynesian women whose attitudes about sex were the answer to a lonely sailor’s prayer.

After three weeks at sea, sex is the last thing on our minds. A calm anchorage, a berth that doesn’t move, a cold glass of wine—these are what we pray for. We must be getting old.

Waypoint: Papeete (Tahiti)

17° 32S, 149° 35W

April, 1999

Big rollers mark Tahiti’s fringing reef. We have crept past the point of land where Captain Cook observed the transit of Venus, past the long outer mole of Papeete’s commercial harbor.

The high mountains of Tahiti’s interior vanish periodically behind dark curtains of tropical rain. After a fast, bumpy trip from the Marquesas, averaging over 150 miles per day, Calypso has been licked clean of every vestige of salt, just in time for her landfall.

The pass through the reef seems impossibly narrow after the blank horizon of the great Pacific.

We threaded a path through the Tuamotus without a single sight of land, trusting to the radar, the GPS, and the autopilot. With these three tools hard at work, I feel like the captain of a responsible, thoroughly reliable crew that never eats and never needs rest.

I make and reduce sail, scan the horizon for breakers through binoculars, double-check the track. You never relax on this passage, as the reefs will eat you the moment you let up your guard.

Now Tahiti lies before us, impossible to miss. We turn through the pass and head for the anchorage off a park full of picnicking Polynesians.

You’re supposed to take a stern line ashore here to reduce swinging, but it’s early in the season, and the anchorage is deserted. We drop a single bow anchor in 60 feet of water, and stare at a city in the heart of paradise. The noise of traffic is deafening, but this seems somehow right in the capital of the South Pacific.

This is a milestone for me. If I die tomorrow, I can say that I built a boat, and sailed it to the South Seas. The biggest risk, however, is getting run over by a speeding taxicab while crossing the street. This is France, after all—France with frangipani.

Waypoint: Raffles (Singapore)

1° 20.5N, 103° 37.9E

October, 2000

We knew getting across the Straits of Singapore wasn’t going to be easy. We motored out of Nongsa, Indonesia, and crept along the south edge of the traffic separation zone looking for a break in the endless line of ships marching east and west through this great choke-point.

We didn’t hang around in Indonesia. A week in Bali was enough for us before we headed north, back across the equator after a year and a half in the Southern Hemisphere.

For us, the South China Sea and the Java Sea were a series of intense thunderstorms, nascent waterspouts, and unlit fishing boats that rarely showed up on radar. Halfway up the South China Sea, I suffered a crippling back spasm—a pure stress reaction—that left me in agony for the rest of the trip through Indonesia.

After two days of rest in Nongsa, I could walk again. You could almost see high-rise Singapore through the haze, and the lure of civilization was overwhelming.

Spotting a break in the traffic, we roared across at full throttle, praying that the engine wouldn’t complain. We crossed the bow of the last ship by no more than 100 yards, and were in the territorial waters of Singapore, a city state that is a near-perfect blend of west and east.

Yes, it is intolerant of dissent, rigid in its laws, oppressive in its ideas. But it is safe and clean to a degree that shames any city of its size in the world. Safe and clean sounded pretty good to us right now.

We motored up the river on the west side of the island of Singapore, with the jungles of Malaysia to port, the modern spires of Singapore to starboard.

Cutting around the breakwater that guards its entrance, we entered the world of Raffles Marina. Efficient dock boys caught our lines and tied us up with a smile, although they checked Calypso’s length with a tape measure to make sure we paid for every inch of dock space we occupied.

Sweating like pigs in the equatorial sauna, we headed eagerly for the showers.

We entered another world. Glass doors slid silently open as we approached, and cool air poured from inside. If you felt like relaxing, a sofa and a table of magazines would prompt you to linger.

The showers were individual marble rooms with separate dressing areas. There were bars of soap, bottles of shampoo, hair driers, warm towels.

It was the longest shower I’ve ever taken. I could feel the tension wash over my back and down the drain. Raffles seemed, at that moment, to be heaven on earth for two weary travelers.

Waypoint: Port Smyth

(Shumma Island, South Mitsawa Channel, coast of Eritrea)

15° 32.27N, 39° 59.42W

March, 2001

Near disaster. In a moment of staggeringly bad judgment, I nudge Calypso onto an isolated reef in the southern Red Sea. Miraculously, it is calm, and a combination of full moon and hand-held depthsounder point the way to deep water just a boat-length away.

It is the worst half-hour of my 30-year sailing career.

When Calypso’s powerful ground tackle finally pivots her into deep water, it’s all I can do to keep standing, my legs are shaking so. The gods have punished my hubris, but spared the lovely nymph—one of their own.

Waypoint: Ithaca (Greece, Ionian Sea)

38° 22.6N, 20° 42E

July, 2001

Idyllic Ithaca, elusive goal of the wanderer Odysseus: It is hot, and cicadas hum in the midday sun.

The ancient limestone walls are bleached a startling white, and our sandals kick up a steady stream of dust on the long walk to town.

Can this tiny island really contain the myth of the ancient warrior-king? Where are Penelope’s loom, the bed built in a living tree, the wretched and doomed suitors? Is that Telemachus sitting, brooding, under an ancient olive tree?

No, it’s just the proprietor of the local Internet café, taking time out for a noontime smoke and a snooze until the sun drops behind the hills, when he will reopen for his eager customers, including us.

This is the heart of the Mediterranean. This is the center of western civilization. This is the land of myth and mist. This is the land of the high-speed Internet connection and the flat screen. It is improbable, but true, where ancient myth collides with Microsoft. We are only a microsecond away from the entire world, even in this ancient place.

Waypoint: Falmouth (Antigua, West Indies)

17° 00N, 61° 47W

December, 2001

We cross our outbound track, tying the knot after almost 30,000 miles of sailing. It has been almost four years to the day since we left this harbor, westbound round the world. We are still westbound, and have ended up where we started. Some might argue we’ve gotten nowhere at all after years of hard work.

I remember my ancient neighbor leaning over the fence in Newport: “Hey Noah, you ever going to get that boat in the water?”

Waypoint: Ft. Lauderdale (Florida, USA)

26° 07.5, 80° 07.2W

March, 2003

The GPS is getting full. Its digital memory of 1,000 waypoints is clogged with the cryptic shorthand of electronic navigation. I scroll through the waypoints one by one, and most bring back instant memories, good, bad, indifferent: Ulegamu, a lonely atoll in the middle of the Indian Ocean; Massawa, a wreck-filled anchorage in desperately poor Eritrea, a land of proud, beautiful people on the east coast of Africa; Trezonia, an idyllic harbor on a tiny island on the western coast of Greece.

Not all waypoints are memorable, of course. Some are merely markers in a route: turn to port here, avoid the reef over there. A series of waypoints labeled B1 through B4 mean nothing until I pull up the chart and realize they define the winding course into Benoa, on the south coast of Bali.

That day comes back clearly: scorching sun, a turquoise channel winding through brown and yellow reefs into a crowded anchorage. This was our introduction to Southeast Asia.

I remember it now, less than three years after that day, but will the meaning of these waypoints be so easily recalled a decade from now?

I live in fear of losing my human memory, where these waypoints are ultimately stored. It is a volatile, selective memory, with no permanent battery to keep the synapses purring along. The human battery will, I know, lose its charge, gradually, inevitably.

After a moment, I turn back to the task at hand: erase the waypoints and routes that define more than four years of two middle-aged lives. After all, Calypso is about to embark on a new life with new owners, and they deserve to store their own cruising memories here, uncluttered by scraps of her past.

Calypso is almost a ghost to me already, this sea nymph who kept her voyager captain a willing prisoner for years. She is scarred here and there by the carelessness of her owners, but to me she is as fresh and beautiful as the day she was launched. I loved her then, and I love her now.

Once upon a time, there was a man who dreamed of building a boat and sailing around the world.

And he did.

-by Nick Nicholson