Keeping warm on a cold night aboard a cruising boat can be a problem, particularly if it’s a boat not equipped with a permanently-installed propane, diesel, or solid-fuel heater. Few sailors carry sleeping bags with more than a +45° comfort rating. (Heavy bags are too warm for most nights.) With a medium or light-weight sleeping bag, some heat is often very nice to have; and, if you cruise fancy (we never have), the same goes for fitted sheets and a light blanket.

Taking the chill off in the evening or early morning and keeping condensed moisture at bay are other reasons to warm the interior of a boat. Very few boats have extensive insulation, other than that inadvertently provided by headliners and cabinetry. So, the space inside your cabin quickly mimics what’s going on outside.

Excess heat can be handled with fans and ventilating devices, but cold is far more inexorable. We’ve found that at the end of any day that includes some motoring, a good diesel engine, kept spotlessly clean to avoid odors, can warm a boat for hours, especially if an access panel is left slightly ajar. But most cruising sailors carry a portable heater, stowed away in a corner, for that chilly weather. And that’s the subject of this report.

The most popular heaters are small 110V models, which are extremely effective when at a dock with available power, and even when anchored or tethered to a mooring.

Most boats now have larger battery banks than a couple of decades ago, and the 110V heaters are increasingly popular aboard boats equipped with inverters to handle computers, appliances, tools, TV sets, microwaves, etc. (True sine wave inverters are expensive, compared with modified sine wave models, but they are worth the expense because they run all AC equipment.)

An alternative is a 12V heater that can be used at moorings and anchorages—as well as dockside when power is available. The downside is that care must be taken, because these heaters use large amounts of electrical power and can exhaust a battery in a hurry.

All such electric heaters are based on the simple fact that if you jam an electric current through a resistant material it gets very hot. That’s what made Edison’s 1879 incandescent lightbulb work. Some of PS’s very senior readers might even remember the brightly-polished copper dish-shaped heaters with a wound-wire coil on a little porcelain cone; they were popular in chilly bathrooms.

There are now available hundreds of small, portable electric space heaters. Bearing names like Holmes, Pelonis, Patton, Marvin, Honeywell, Vornado, etc., and they invariably clog hardware store aisles in early winter. Many are made in China. Some are simple, with single heating elements and single fan speeds. None is very complicated, other than having multiple heat and fan levels, thermostats and overload and tip-over shut-offs.

One feature they all share: The fans make noise, which can be irritating on a boat where one of the joys is nighttime quietude so profound that tiny waves can be heard lapping at the hull.

Practical Sailor’s limited collection of heaters is intended to cover a range of types and prices. Included are four 110V heaters, three 12V models and one alcohol-fueled heater from Origo, a Swedish company.

The Testing

These heaters were run for hours. The switches were manhandled. The thermostats were checked repeatedly. The overload and tip-over switches, if included, were exercised several times, and reset intervals were checked. Our three most important tests, yielding comparable measurements, were of heat output, fan performance, and noise.

]For simplicity, the testing was done with the heaters on high temperature and fan speeds. The chart shows how many heat and fan settings each unit offers.

The high heat output was measured—both where the air emerges from the fan and a foot away—with a Raytek MT4 model infrared thermometer, which has a laser-sighting feature that assures well-positioned readings.

Comparative fan output was checked simply by placing a precision anemometer (Speedtech’s Skywatch, which is a very sensitive instrument) a foot from the front of the fan and “feeling” for the greatest velocity. Fan performance is important because—as is known to those who spend chilly nights in a quarterberth with the heater on the floor in the bow—the warm air sorely needs to be distributed throughout the boat.

The noise level was measured, again at a foot from the front of the heater, with a Quest decibel meter. In general, on “high” speed, these heaters are almost as noisy as freshwater pumps. The heater fans ranged from the mid-50s to high 60s on the decibel meter; in prior tests, PS found that the quietest freshwater pump was at 75 decibels.

Finally, three testers, who (after the measurement tests were completed) examined the materials and workmanship of each heater, reviewed the data shown on the chart above and made judgements about which heater seemed preferable.

The Test Results

For heat output by the electric heaters, the Holmes 110V heater produced the highest temperature airstream, with the 12V Back Seat heater second, followed by the 110V Caframo and 12V MarinePro Ceramic.

For air speed, the 12V MarinePro Ceramic rated highest, with the 12V ThermTech second, followed by two 110V heaters—the Honeywell and Patton.

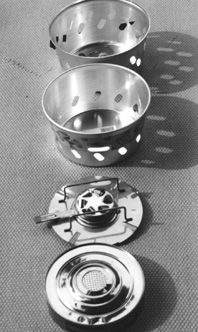

On the noise issue, the 12V heaters were all noisier than the 110V heaters. The quietest was the Caframo, followed by the Honeywell, the Patton and the Holmes. (For a brief explanation of noise, see the caption under the photo on page 8 of three heating elements.) The quietest of all was, of course, the Origo alcohol heater which, having no fan, made no noise whatsoever. A special case, the Origo made good heat (288° on its top surface), but depends on heat rising to provide some distribution of the warm air.

In all cases, the heaters’ overheat and tip-over shut-offs, if fitted, worked satisfactorily. In the case of the Origo, tipping it on its side (with a nearly full load of fuel) produced nothing untoward. Unlike the electric heaters, the Origo does require that the cabin be vented. (Although a half dozen attempts were made, the term ‘ceramic,’ as applied to heaters, could not be clarified. It apparently means only that the metal wire or strip that creates heat is held in place or positioned with an inexpensive nonmetallic mineral—clay—to insulate it and provide added protection from breakage. If one of the manufacturers would like to write and explain more specifically, PS would be happy to pass the information on to readers.)

Conclusions

All testing is comparative, but it’s difficult to compare the Origo to the electric heaters. The judgment of the testing crew was that the Origo was, like the Origo stoves, a bit difficult to fuel up.

Fueled and assembled, the Origo makes heat in exactly the same fashion as the Swedish company’s stoves, which probably are the safest alcohol stoves on the market. The alcohol fuel is contained in a detachable canister filled with fibrous material that passes alcohol vapor to the top surface, where it burns. Filling the canister, which can only be done when the canister is cold, is a bit difficult. The heat level is controlled with a swivel lid that limits the amount of flame. A full load of fuel (1.2 liters, which is about 5 cups) will last for seven hours, which is about right for a good night’s sleep. With the flame turned down, the fuel would last longer.

Of the 12V heaters, the higher-priced Back Seat Heater tested slightly better than the other two 12V heaters. PS could not get the switch to turn on the heat on the small MarinePro All Season, which is really meant for heating a small, limited area.

Unless a boat has scads of available power and a safe place to mount them, PS does not recommend these 12V heaters. None has overheat shut-off switches, so extra care in using these heaters would be required, even if they were permanently mounted on a bulkhead.

For the more popular 110V heaters, with all factors considered, the Caframo heater tested the best. For those who live in cold climates, it even has an anti-freeze setting, which kicks the heater on when the temperature drops to 38°. It is the most expensive.

The second best in this test was, in PS’s opinion, the inexpensive Honeywell, which has some nice features, such as both heat overload and tip-over switches, and directional switch on the fan output, and a clever child-proof fan/heat switch.

Also With This Article

“Value Guide: Portable Heaters”

“Hot Stuff!”

“Heating Elements Exposed”

Contacts

• Caframo, 800/567-3556, www.caframo.com

• Holmes & Patton, 508/564-5602, www.PattonElectric.com

• Honeywell, 760/597-1606, www.Kaz.com

• MarinePro, 800/233-7009, www.das-roadpro.com

• Origo, 941/355-4488, www.origo-sweden.com

• ThermTech, 800/659-8271, www.thermtech.com