Sailors who are enamored with performance, European styling, and the interior joinery and construction standards you expect from Scandinavian craftsmen should take a close look at the Finngulf 37. Those who have no intention of shelling out $300,000 for a semi-custom racer-cruiser built in Finland might want to test sail the boat anyway, because it is, above all, an enjoyable ride.

Based in Pohjankuru, Finland, Finngulf has been producing boats since the 1980s, but the line took a marked shift five years ago, when Karl-Johan Strahlmann, who was project manager for the Swan 45, was contracted for the design. Previous boats were designed by Swede Haken Sodergren, and these are still regarded as competitive, well-built sport cruisers.

The owner of the boat we sailed, Horst Lachmeyer, has a mantel full of PHRF series cups from New England, most recently the 2005 Marblehead (Mass.) to Halifax (Nova Scotia) race, aboard his previous boat, a Sodergren-designed Finngulf 38.

The 37 follows other Strahlmann designs, the 28, 33, 41, and 46, all of which are aimed at the racer-cruiser niche. So far, it seems Strahlmann has hit his mark. The 46 finished first corrected time in its class and fourth overall corrected in the 2004 Atlantic Rally for Cruisers, and smaller boats have done well in club racing throughout Europe.

Design

Strahlmann wanted to design a boat that was quick and fun to sail or race without bowing to IMS-driven design changes (such as internal ballast) that would give it a faster rating, but do little to improve overall performance—or safety and comfort in a seaway.

With a fine entry, bulbed keel, and a tall fractional rig, the Finngulf 37 has the hallmarks of a European-styled performance cruiser. In profile, the modest freeboard and angled coach roof present an appealing, streamlined shape. It has just enough overhang at the bow to handle ground tackle without defacing the bow with dings. Its canoe-shaped underbody is fairly flat, and in plan view its forward sections are finer than others of this breed. It has a keel-stepped, two-spreader Selden mast with the spreaders raked back at a 15-degree angle. The chainplates, anchored to a structural grid below decks, are set well inboard allowing for close sheeting angles. All of the lead ballast is concentrated in the bulbed keel. The biggest change over the 1980s Finngulf is the wider stern, found on just about every modern performance boat today.

Overall, the design does an excellent job of minimizing the inevitable compromises that come with the genre. The biggest compromise? Most of the available volume for stowage space is aft, not the best, or most convenient, place to pile up gear and supplies.

On Deck

Although you can order a Finngulf with non-skid fiberglass decks, no one seems interested. Most of the buyers prefer the standard teak deck. The modern technique of vacuum bagging and gluing the teak to the deck has eliminated one of the biggest problems with teak decks—the hundreds of bunged fastener holes that, if not cared for, will inevitably allow water to leak into the deck core.

The layout is well thought out. The placement of hardware minimizes friction on running rigging and you’ll find no surprise toe-stubbers when moving about. Passage fore and aft is clear outside of the shrouds.

The self-draining anchor locker, accessible through the deck, is about average for a boat of this size. We would upgrade the locker hardware. The stamped stainless-steel lifting ring is weak, and the latch is also deficient. A better choice here would be a heavy-duty twisting latch or two that can be adjusted for a tight seal. We’d also raise the 25-inch lifelines at least 3 inches, 5 inches for serious offshore work.

Standard hardware is Rutgerson (travelers and turning blocks) or Andersen (winches), although the buyer can specify his preference. As one would expect from a performance cruiser, the running rigging is well organized, with all control lines led aft to the cockpit.

The mainsail features end-of-boom sheeting, a desirable feature that not only places the sheet where it belongs on the boom, but brings the traveler within arms reach of the helm. For the cruiser, the drawback of end-of-boom sheeting is that it can divide the cockpit fore-and-aft into two sections, as it does on the Finngulf.

Accommodations

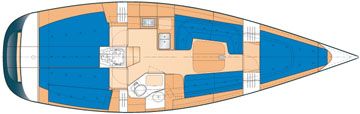

The Finngulf 37 is “stick-built,” with all furniture and bulkheads tabbed into place after the hull has been molded. A buyer can move everything but the main bulkheads, engine, and mast step, so long as his pockets are deep enough. The standard layout—moving from stern to stem—is quarter berths port and starboard, galley to port, head and nav station to starboard, an L-shaped settee to port, a settee to starboard, and a V-berth forward. The standard layouts feature either bunk berths or a twin bunk in the starboard quarter berth.

The teak joinery is what you’d expect of Scandinavian craftsmen, right down to the back sides of ceiling panels, which are sealed to ward off moisture due to condensation. One change we’d request: angled corners or cambers on the companionway steps to allow easy passage on a heel. PS poked deep into the dark corners of the boat and found no rough edges, poorly saturated glass, or ugly secondary bonds.

Systems

Though the boat we sailed had the older MD 2030 Volvo, a 30-horsepower Volvo D1-30 is now standard. These are solid engines with Perkins blocks, exceptionally efficient and quiet when paired with the saildrive, essential to the design brief of maximizing performance.

We found a few installations we didn’t like. The propane locker and hose connections didn’t meet standards set by the American Boating and Yacht Council.

The conversion to 12-volt DC/110-volt AC appeared to be carried out well. All wires were labeled at both ends. With regards to plumbing, we didn’t like the Christmas tree assembly of elbows and valves under the galley sink, nor the seacock installation there and in other locations below-waterline. A flanged seacock with a backing block is preferable. Overall, system access was exceptional.

Performance

Our test sail took place on Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay and Block Island Sound, in winds of 5 to 12 knots and seas of less than 3 feet. Light airs curse the Baltic Sea in summer, so it was no surprise that the Finngulf, with her working sail plan, a 110 percent jib, accelerated well in the 5- to 7-knot winds early in our sail. Speed over ground while close reaching hovered between 5.0 and 5.6 knots for most of the morning, but by the time a 10- to 12-knot sea breeze kicked in, we generally held 6.0 to 6.6 knots close reaching and 6.6 to 6.8 knots on a beam reach. The highest sustained speed our GPS recorded was 7.2 knots beam reaching, still under the conventional sail plan. It tacked through 90 degrees true, and the helm was always firm and responsive, even in the whispers.

As expected, the boat was quiet under power. At a cruising speed of 6.6 knots at 2,500 rpm we registered 67 decibels in the cockpit and 72 decibels in the galley. (Normal conversation is about 60 decibels.) It handled well under power, turning quickly and smoothly at full throttle. Control while backing under power was good, though the wide gap between the rudder and the saildrive’s prop means prop wash isn’t as effective for bumping the stern out in forward when side-tied to a dock.

Conclusions

The Finngulf 37’s high-quality design, construction, and finish makes the price palatable, particularly to those who highly value style and speed. If the boat holds its value here in the U.S. as older models have done in Europe, all the better. However, it shouldn’t be a tall order to request that the boat meet or exceed ABYC standards. Insist on first-rate components throughout.

While the standard layouts suit short-term cruising, if you’re planning extended cruises or multiple weeks with two couples, you’ll have to tame your inner packrat, or work closely with Finngulf to increase available stowage space, especially in the main saloon. And if you’ve no intention of spending more than $170,000 on a performance cruiser, there’s a 12-year-old boat for sale in Connecticut that might interest you—Lachmayer’s decorated Finngulf 38, Gold Watch. He’s moved on to smaller, faster things.

Contact – Finngulf Yachts, +3 58 20 741 4200, www.finngulf.com.

Also With This Article

“Hits and Misses”

“Finngulf 37 In Context”

“Construction Details”

“Critic’s Corner”