We used a four-stroke Honda BFP 9.9 horsepower outboard (92 pounds) and a Mercury ME 9.9 (84 pounds) four-stroke to test eight engine brackets that can be used on sailboats. Testers figured the 9.9 engines to be the middle road between the commonly used 5 horsepower and 25 horsepower. Five manufacturers responded&emdash;Fulton, Garelick, Marine Tech (Panther), JR Marine, and Garhauer&emdash;with eight different brackets, four manual and four electric, all rated for four-stroke 9.9 engines. The main test criteria were ruggedness, quality of materials and workmanship, ease of assembly and mounting bracket on a boat, clarity of instructions, ease of mounting an engine on the bracket, ease of operation, and price. For the purpose of comparison, brackets can be divided into three categories: fixed or stationary outboard mounts, retractable manual lift engine mounts, and electric trim and lift/tilt mounts. Choosing the mounting bracket thats best for a certain sailboat will depend on the horsepower and weight of the outboard to be used, the length of its shaft, and where it is to be mounted. Among testers top picks were the Garelick pump-action 71092 for best manual engine bracket and the pricey Garelick 71095 for the best electric bracket. For the budget-minded sailors, we recommend the inexpensive Fulton MB1820 or Panther 40.

****

]In the wake of our recent test of four-stroke 9.9-horsepower outboard engines (“9.9 Outboard Rumble,” June 2007), it seemed logical&emdash;if not necessary&emdash;to revisit a perennial small sailboat topic, outboard engine brackets.

During the course of that test, it became abundantly clear that the move toward quieter, more efficient four-stroke engines had many admirable benefits, but providing much needed relief for our backs and shoulders is not among them. Our top choice in that test, the Mercury F9.9M, tips the scales at 84 pounds.

Ever since Ole Evinrude first attached his little gas-engine “outboard” to the transom of a small rowboat nearly 100 years ago, people have been designing and building brackets to make the chore of lifting and lowering them easier. Over the years, larger and sturdier brackets have become available to handle the larger and more powerful engines that are being found on todays sailboats. Some are better than others.

These brackets generally use mechanical advantage, or electrical power to reduce the amount of effort required to get the propeller out of the water. Some tilt; some provide vertical lift; some do a little of both. For the purpose of comparison, they can be divided into three categories: fixed or stationary, retractable manual lift, and electric trim and lift/tilt.

The type and characteristics of the mounting bracket thats best for a certain boat will depend on the horsepower and weight of the outboard to be used, the length of its shaft, and where it is to be mounted. Larger sailboats should use a motor with a longer shaft. Steering is done through a rudder, but consideration of whether the motor is manual or electric start and ease of getting to the motor may influence the type of bracket needed.

Fixed brackets are appropriate for smaller boats with low or cut-away transoms like the Balboa 26 and the Grampian 26, which allow for the engine to be tilted over them. Some are simple, inexpensive, extruded aluminum while others are heavy-duty cast bronze devices specifically designed for a particular boat. Retractable manual lift brackets typically are spring-loaded to allow manually raising or lowering the motor. Each spring-assist bracket has a narrow range of motor weight at which it operates best. Matching the number and size of the springs to the weight of the motor is one way of figuring out which retractable manual bracket will work best. Electric trim and lift brackets use hydraulic or electric pumps that operate off a boats 12-volt battery.

What We Tested

We asked eight manufacturers to submit brackets that could handle a current production, four-stroke, 9.9-horsepower outboard. Our test engines were a four-stroke Honda BFP 9.9 horsepower weighing 92 pounds and a Mercury ME 9.9 horsepower weighing 84 pounds. Since four-strokes are usually heavier and produce a higher torque than two-stroke motors, these brackets are understandably heavier and more ruggedly built. Testers figured the 9.9 engines to be the middle road between the commonly used 5 horsepower and 25 horsepower.

Five manufacturers responded&emdash;Fulton, Garelick, Marine Tech (Panther), JR Marine, and Garhauer&emdash;with eight different brackets, four manual and four electric. All appeared stouter, better-constructed, and more heavy-duty than the last time

Practical Sailortested outboard brackets (Oct. 15, 2000 issue).

The main test criteria were ruggedness, quality of materials and workmanship, ease of assembly and mounting bracket on a boat, clarity of instructions, ease of mounting a motor on the bracket, ease of operation, and price. Other considerations were the number of trim options, hardware and accessories included, clearances and tolerances, maintenance considerations, corrosion resistance, and warranty coverage.

Manual

Fulton MB1820

The MB1820 is the strongest of the Fulton line of brackets, but it was also the lightest and least expensive of the eight Practical Sailortested. The metal is lightweight, unpainted anodized aluminum with stainless steel (SS) fasteners and a polypropylene mounting board. The SS balance springs are smaller than those used on the other manual units tested.

During our initial testing of the bracket, both testers had trouble lifting the 9.9s using the Fulton, despite Fultons claims that the MB 1820 handles motors up to 130 pounds. At second glance, testers realized this particular unit was defective as its bottom springs would not engage. A phone call to Fulton, and another bracket was on the way the same day. The replacement unit was easily installed following the simple, well-written instructions, and the four-spring unit operated much better.

The lifting handle is small, only 3 inches wide, but it includes five lift-position notches with a unique set of springs that assist in keeping the notches engaged. The Honda motor has a hinged lifting handle that interfered with the brackets lifting handle, making the Fulton basically unusable with this motor unless the Honda handle is removed. Lowering and lifting the 84-pound Mercury was easy, and the Fulton springs had just about the right tension for this size engine, in testers opinions. However, its lightweight, narrower mounting footprint and overall looseness does allow for some wiggle, so we would not recommend it for heavier motors.

Bottom Line

: An inexpensive, no frills bracket that will get the job done, the MB 1820 is our Budget Buy among the manual brackets.

Garelick 71091

Garelick offers a wide selection&emdash;the catalog lists 16 different models of stationary, manual, and electric brackets&emdash;to accommodate various style and weight motors.

The 71091 manual lift model is designed for four-stroke motors up to 25 horsepower and 175 pounds. A high-tensile-strength safety cable and four 5/16 x 3-inch carriage bolts are included. The instructions were limited but simple, and the unit was easy to install.

The bracket has a wide boat-mounting plate that has 12 pre-drilled square holes for mounting flexibility. Construction is heavy-duty black anodized aluminum, with four stainless steel springs, stainless steel hardware, and a large, 2-inch-thick, 11-inch-wide, polypropylene motor-mounting board.

The stainless steel springs are quite strong, a requirement for coping with the heavier motors. The 6-inch lifting handle is wider than others we tested, and it has four locking positions with unique safety knobs on each side to tighten it in place and a spring mechanism to hold it in the notches. However, testers were not able to get the motors down and locked in the final notch. The springs seemed too strong (tight), as if they were designed for heavier motors. Also, operating the bracket without a motor attached could cause serious injury as the lifting mechanism abruptly snaps back to the up position. Garelick does offer other models for lighter, two-stroke motors.

The 71091 and all other Garelick models tested each came with a 4-foot, vinyl-covered safety cable with a stainless steel carabineer to secure the motor to the boat. The other product instructions only mentioned safety cables as a good idea.

Bottom Line

: This unit is well-constructed and hefty. Its a little more expensive, but the value is there and it would be our choice for the really heavy motors.

Garelick 71092

This unit looks similar to the Garelick 71091, but it has a unique manual hydraulic pump and handle. It also comes with mounting nuts and bolts and a safety cable. Testers found its 26-inch long removable aluminum handle very easy to use. The side-to-side pumping action takes the strain out of raising and lowering the heavier motors. It takes about 12 pumps to go the full 14 inches of continuous vertical height adjustment, and the 92-pound Honda came up with little effort. To lower the motor, the pump handles notched end is used to turn a relief valve, and the motor slowly drops down. (Note: The valve must be retightened or hydraulic oil could leak out.)

However, we do have some concerns about where to store the handle and the possibility of losing or dropping it overboard. Wed like to see a locking pin, screw-in bushing, or optional tether cable. A piece of 7/8-inch pipe or a broom handle would make a handy backup.

Also, the pump handle moves to the right about 20 inches when facing aft and could be a problem bumping into a main motor, rudder, or swim ladder. Buyers should carefully consider where to locate the bracket on the transom before purchasing and mounting it. However,

Practical Sailorfound this pump action to be a really nice feature over standard manual lift brackets.

The 71092 also includes a stainless safety strip that easily latches on a bolt to hold the bracket and motor in the up position.

Bottom Line: The Garelick 71092 manual pump model is Practical Sailors Best Choice. It got a lot of attention because of its unique pump action, smooth operation, and ease of lowering and raising the test motors.

Garhauer Z2275

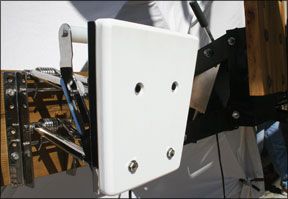

Garhauer is an OEM manufacturer that sells the Z2275 exclusively through Catalina Direct. The manual, adjustable bracket is sharp looking, with all electro-polished stainless steel tubing and a white UV-stabilized marine plastic motor mounting board that has a curved metal lip on the back for the engine fasteners.

The lifting handle is 4 inches wide, enough to fit a mans fist. The bracket is fairly lightweight at 21 pounds, but Garhauer claims it can handle a motor up to 15 horsepower with a minimum weight of 125 pounds. It has four stainless-steel springs, 17 inches of vertical lift, and three lift positions.

The pivot points have bronze bushings and compression tubes to allow clear, friction-free lifting movement. The unit did not come with any instructions or mounting hardware, but the long mounting bracket does have 12 pre-drilled 5/6-inch boltholes for maximum mounting flexibility.

We found the up-down operation a little rough, with no extra springs to hold it in the notches and the main springs a little too tight for lifting/lowering both test motors. Testers had difficulty getting the loaded bracket into the down position. Once locked down, it was difficult to release it for lifting primarily because the test motors were too light for the four-spring bracket.

We contacted Catalina Direct, who sent us a three-spring bracket (Z2274) designed for smaller motors. This one operated much better with the test motors. Garhauer also makes a two-spring model for even lighter engines.

Bottom Line: Testers found the three-spring Garhauer easy to use and priced right, not to mention it has the longest warranty (10 years) of any mount tested. We recommend it for budget-minded boaters with small, lightweight engines.

Electric

Garelick 71095

The 71095 electric power-assisted motor bracket is one of Garelicks larger models. It was the heaviest and most expensive bracket we evaluated, weighing in at about 72 pounds.

With a 15-inch by 14-inch, double layered (polypropylene and aluminum) motor mounting board and a hefty 12 inch by x 9 inch mounting bracket, this thing is big. The heavy-duty aluminum frame has a triple-coated finish (anodized, E-Coat, and black-powder coated). It comes with large half-inch SS bolts and washers, bronze bushings, and brass locknuts. The instructions and diagrams are well written, and the electric hook-up was straightforward. The unit quickly raised and lowered our motors smoothly and without difficulty.

Bottom Line: The 71095 is our Best Choice among electric brackets, but its pricey. It handles the big motors smoothly and without effort, and it was easy to mount and hook up to the power source.

JR Marine 2500

This is a well-built, boxy looking electric bracket with ample lifting capacity, a 19-inch setback, and infinitely adjustable vertical lift up to 14 inches (3 inches down and 11 inches up from horizontal).

It is made of heavy, extruded structural aluminum with double layered, powder-coated paint, stainless steel bolts and hardware, and a laminated-maple mounting board.

The instructions were thorough, and it was easy to mount with its 5/16-inch stainless steel nuts and bolts, although we did have to drill open the mounting holes a little. Also included were a rocker lift switch, a breaker, solenoids, and

8 feet of electrical cable.

The electrical hookup is simple and easy to follow. The mounting plate comes with eight pre-drilled holes, but the manufacturers literature states the plates can be custom drilled, if required. We did have a problem with a wire coming loose from the resettable circuit breaker. We suggest not using crimp connectors, especially for marine use. We had to solder in a new fuse holder. Operation was smooth and effortless with both our test motors.

Bottom Line: The JR Marine 2500 is a well-built unit, and it operated flawlessly. It is offered direct from the manufacturer, which allows some customizing and cost savings.

Panther 35 and 40

These are heavy-duty, electric trim-and-tilt auxiliary motor brackets. They both can handle four-strokes up to 150 pounds. The main difference between the two is that the newer, less expensive Panther 40 has one 8-inch setback position whereas the Panther 35 comes with a 7.5-inch setback and can be adjusted to a 13-inch setback. However, the 40 could conceivably have six permanent vertical positions by changing the location of the pivotal bolts. Neither one allows adjustable vertical lifting.

The 14-page instruction book is excellent, including a template for the mounting screws. However, we could find no explanation for two extra holes on both the bracket plate and motor mounting plate.

Both units come with a “breather tube” to allow the electric actuator pump to operate. This tube must be run into and fastened inside the motor housing to prevent water entry. The rugged 35 is made of powder-coated cast aluminum. The 40s transom plate is powder-coated 3/8-inch extruded aluminum, and the motor mounting plate is -inch formed channel. The mounting holes are large and require -inch bolts and large washers (not provided).

Bottom Line: Practical Sailor found these to be very rugged electric motor mounts, with smooth operation to tilt good-sized motors, but they don’t have any vertical lift, and so may not be appropriate for most sailboats. For those who have low transoms and light motors, the Panther 40 is our Budget Buy.

Conclusions

At first, testers struggled to get our motors down and locked in place with all three spring-assisted manual brackets. It would be nice to be able to adjust the tension of the springs for a specific weight motor, but that not being possible, it is very important&emdash;when using a manual lift&emdash;to select the right model for the actual weight of your motor.

Among the manual brackets we tested, the unique pump-action Garelick 71092 was as nearly as easy to use an electric, but doesn’t require all the fuss and maintenance of running electric cables. When considering todays heavier motors, it is a nice innovation for those with bad backs who don’t want to go electric. Its our Best Choice. Fultons MB1820 is our Budget Buy for lighter motors. It is an inexpensive, no frills unit that does the job. The Garhauer Z2275 is a good choice for those looking for a mid-priced bracket for a small outboard. For boaters seeking a heavy-duty manual lift for a larger motor&emdash;and who don’t want to spend the extra money on the hydraulic 71092&emdash;the Garelick 71091 is a good choice.

The four electric outboard motor brackets

Practical Sailortested were all quite different. If you have trouble lifting and lowering the heavier outboard motors, or if your transom is hard to get to, and you can spend a few extra bucks, you should consider these power-assist brackets.

The Garelick 71095, the

Practical Sailor Best Choice for electric brackets, is a hefty, easy-to-use unit that would serve well in extreme conditions. For the budget conscious, the JR Marine 2500 is well-constructed with precision-machined aluminum, a large wooden mounting board, and it operates smoothly. The Panther 40 is a sturdy, compact electric bracket with smooth operation. It can handle heavy motors and is well suited for small to mid-sized boats with short transoms. Designed for auxiliary outboards, these units have only tilting action and no lifting power, so they would have real limitations on most sailboats. But they are mid-priced and definitely a Budget Buy if you have the right boat.