The U.S. Coast Guard Academy has always been a strong advocate of sail training, but for decades, the tall ship Eagle has held center stage. Of course, the Coast Guard Academy has always maintained a fleet of sailing vessels at its New London, Conn. campus, but the boats were usually hand-me-downs from the U.S. Naval Academy—boats that had been sailed hard for two decades or more.

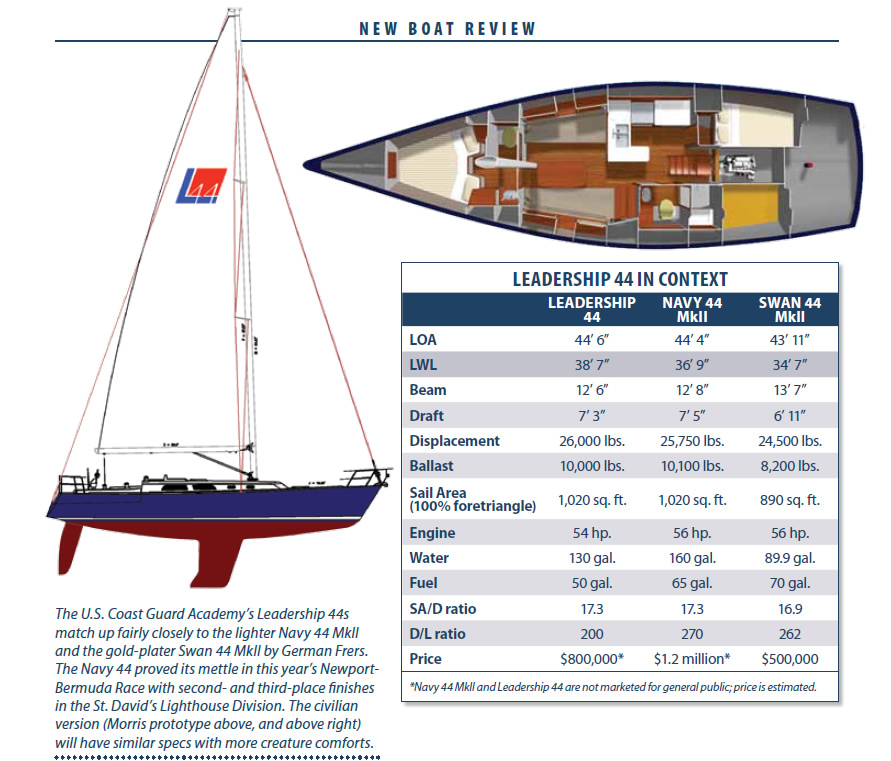

This time, when the Naval Academy received its new fleet of Navy 44 MkIIs ($1.3 million per boat, including cost over-runs), the Coastie cadets set their sights on a new boat, too. Largely due to the efforts of the U.S. Coast Guard Foundation, they got it: the new Leadership 44, built by Morris Yachts, a company best known for its high-end semi-custom yachts. As with the Navy 44 MkII (PS, August 2008), the boat’s designer is David Pedrick, whose extensive resume ranges from America’s Cup boats to capable cruisers.

Fewer and fewer new sailboats are set up for 24/7 underway operation, so when we come across one that has the features we expect in a true offshore workhorse—offshore sleeping berths, ventilation in rough weather, a galley and head that work well underway, and a sail plan that’s efficient and easy to handle—we naturally get excited. At its heart, the Leadership 44 is a service academy boat, and its mission is to provide cadets at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy with both leadership and small-boat seamanship experience. It is more than just a platform for building teamwork and seamanship, however. Sailing skills learned at the academy often get put to use in the real world.

350

250

Now-retired USCG Capt. Kip Louttit often recalls his time spent sail training at the Coast Guard Academy. Later, as a junior officer aboard a cutter responding to a mayday call from the crew of a sailboat with engine trouble and a seasick crew, he put that training to work. Instead of plucking the crew from their unpleasant but non-life threatening seafaring experience, he and another crew member from the cutter were transferred from to the sloop. They set a reefed mainsail and jib that dampened the motion, got the engine started, charged the batteries, and then continued under sail for a couple of days to Shinnecock Inlet, where the local Coast Guard station crew took over. During the passage, they helped the owner and crew to recover from their misadventure and demonstrated how to handle an offshore passage.

Design Objectives

This sail training boat is neither an all-out-racer nor an ocean-crossing iceberg chaser. What the Coast Guard wanted was a sailboat to teach leadership skills as well as small-boat seamanship. And the reason that neither the Navy nor the Coast Guard could simply head to the Newport or Annapolis boat show and pick their boat form the fleet on display, was that nothing on the floating shelves quite met their needs. Both institutions realized that their demand for a sail-training boat required a vessel that could be driven hard and endure year after year of rough treatment ranging from wicked squalls to groundings.

Based on the Academy’s experience with its old Ludders yawls, it was clear that the demands of the mission were far more challenging than what individual owners or even charter companies placed upon mainstream production boats.

In short, the structural requirements needed to be upgraded, and functionality superseded luxury, aesthetics, and finish. For both the Coast Guard Academy and the U.S. Naval Academy, the right boat needed to offer the performance of a racer, the carrying capacity of a cruiser, and the durability of a workboat.

Once Pedrick had a clear picture of what the Coast Guard was looking for, he took the lessons learned from the Navy 44 project and designed a lighter-weight, fuller canoe-body sloop with a fractional rig sail plan and a carbon-fiber spar. The mission was clear, and what the superintendent of the Coast Guard Academy signed off on was a boat with, “contemporary lines, simplified rig and improved sail plan, that will meet the rigorous demands of the Coastal Sail Training Program and give the Academy excellent performance for years to come.”

Engineering

Taking weight out of a boat is easy if you’re not concerned about strength and stability. But if you are, effective engineering is the only answer to the challenge. Less ballast cuts down on weight, but you will sacrifice when in comes to the limit of positive stability or (LPS), also known as the angle of vanishing stability (AVS). Because the primary mission of the L44 lies in the coastal domain, reducing weight to increase light-air sailing ability could be justified. So the decrease in ballast and LPS was acceptable, and the result still delivered a boat that would have no trouble fulfilling the 115 stability index required for the Newport to Bermuda Race, if participation was on the agenda.

Adding a carbon mast was another weight-saver, paring away pounds where it counts the most. But when you get to the hull laminate, weight reduction with strength retention becomes more and more costly.

In order to shed some hull-and-deck weight, Morris used SP-High Modulus to engineer the laminates. The 30-year-old composite engineering company has an aircraft-savvy approach to boat building. Their SmartPac B³ system uses the designer’s files and finite element analysis to come up with a layer plan for putting the right amount of reinforcement in every given area of the boat. Then SP uses computer-controlled nesting software and fabric cutters, much the way a sailmaker cuts panels. Cloth, mat, stitched fabric, and foam are cut like parts of a tailored suit.

The process can be leveraged to favor light weight, low cost, or high strength, but not all at the same time. An advantage to the system is material standardization and less waste and clutter. The challenge lies in picking the right safety margin. Sailing loads are predictable, but wave impacts on decks or hitting a sharp edge of a large piece of flotsam may put loads where they weren’t anticipated, so how to value toughness and point load resistance to penetration also counts. The Leadership 44 mission statement doesn’t reflect as much open-ocean sea time as the Navy 44, so a slightly lower scan’tling could be justified.

Dr. Paul Miller, a naval architecture professor at the U.S. Naval Academy and consultant on the design of the Leadership 44, performed original research on the development of the laminate schedule for the Navy 44 MkII. He’s quick to point out that the Navy boat is built to a higher scan’tling and utilized more laminate in the hull and deck.

Both boats were resin-infused, a process that improves the slot filling in the core, increases the fiber-to-resin weight ratio and decreases void content. The scan’tlings of each boat fit the mission of the vessel.

The original McCurdy and Rhodes Navy 44 sloops, also built to robust scan’tlings, were pressed hard for 20 years. The boat’s success proved that enhanced structural strength is essential to achieving the durability required in a sail-training craft.

On deck

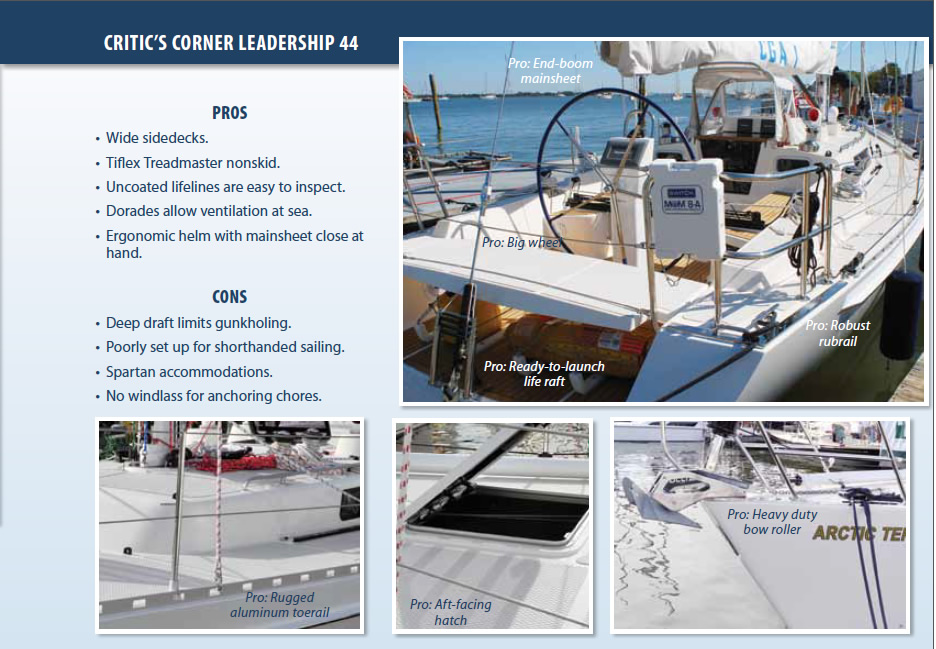

The rig and deck layout of the Leadership 44s signify a performance sailboat with a sea-going pedigree. Though not principally designed as a long distance passagemaker, the new boat bristles with offshore attributes. The low-profile cabinhouse, modest sized windows, and absence of ports in the hull emphasize impact-resistance and a readiness to handle breaking waves. The functional rub strake, a hard-won battle during the design of the Navy 44 MkII, made its way to the Leadership 44s.

The rig and rigging of the Coast Guard boat reflects the modern trend of a large mainsail and smaller jib, but by keeping shrouds inboard and avoiding excess spreader length, the ability to use a larger, over-lapping genoa remains an option. The Navy 44 MkII stuck with piston-hanking headsails and the belt-and-suspenders redundancy of a removable forestay and running backstays on an alloy spar. In this case, the designers went with the tried-and-true arrangement that would also give cadets experience with setting, reefing, and dousing non-furling sails. Whether the convenience of roller furling outweighs the experience of time on the foredeck that comes with conventional sails remains to be seen.

The Leadership 44’s rig is simpler than that of the Navy 44. A welded single-point chainplate cluster through-bolts to a no-nonsense double bracket. This transfers rig loads to a sizable knee that’s bonded into the hull and deck. The fitting is directly above the upper berths in the main saloon, so whomever draws the top bunk will soon learn whether the engineering is a success by the presence or lack of a persistent drip-drip.

The Navy 44 MkII took a different approach, creating a monocoque form incorporating the hull, deck, and chainplates. Time will tell which approach staves off the top bunk water-torture test, a recurring problem on the original Navy 44s, which featured a notoriously leaky stainless-steel angle bracket to carry the loads into the hull.

It’s nice to see a hull and deck that are designed with on-deck work as the priority. The Leadership is pleasantly free of bulging cabin sides, excess freeboard, obstacles to vault, and slick areas of untextured gelcoat. Ergonomically designed for safety and freedom of movement, particular underway, the layout offers a good model for the way a cruising boat should look.

The Tiflex Treadmaster nonskid (rated best in PS’s nonskid test, July 2012) is the epitome of un-slipperiness. Coachroof handrails are no-nonsense stainless steel, through-bolted in a fashion that is sure to keep them in place. The 30-inch double lifelines, securely attached stanchions, and effective geometry of the bow and stern pulpits are consistent with the leads for jacklines and clipping points in the cockpit—all demonstrating an ongoing concern for crew safety.

There’s no question that the design team was comprised of experienced sailors seeking to optimize running rigging and hardware location. Winches and rope clutches team up where they make sense. Gone are the six lines running to a single winch, a choke-point we often see on many over-clutched production boats. The self-tailing winches are situated where the person grinding has plenty of room to work and is not constrained to 280-degree arc. The helmsperson is isolated by the traveler, within easy reach, and a bridgedeck over the semi-open transom doubles as a carport for liferaft storage.

Belowdecks

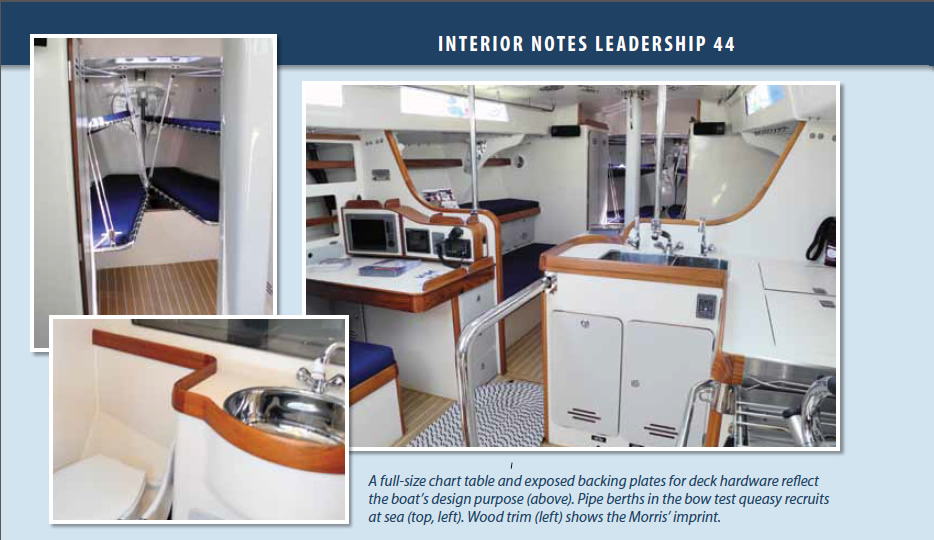

Though far from getting a nod of approval for sumptuous accommodations, this Pedrick/Morris interior is an elegant vision of Spartan utility. The open interior is well-ventilated with four large dorades, and it succeeds because of what it lacks as well as what has been installed. Best of all, the accommodations work at varying angles of heel and make being underway a pleasure rather than an ordeal. In some ways it’s a retro look at the utility of going to sea.

A foursome of berths is given priority in the main saloon. This is a place where an off-watch crew can get some sleep. Amidships, the motion is lessened and good ventilation optimized. There’s even a foursome of pipe berths in the forepeak that will be just fine for off-the-wind sailing or while at anchor. The head and galley are also optimally located and work well while underway.

The treat, however, is that the capable crew at Morris Yachts just couldn’t help but trim things out with just enough wood to deliver a hint of the their abiding forté. The result is a no-nonsense interior with a spacious chart table, very user friendly L-shaped galley with a deep double (small/large) sink and a heavy-duty centerline restraining bar that keeps the cook from landing in the nav-station when the boat is on a rough starboard-tack beat.

These accommodations work well in port and even better when underway.

Photo by Onne Van Der Wal courtesy of USCG

300

Systems

The ubiquitous Yanmar naturally aspirated 4JH4 was the engine of choice for both the Coast Guard and Navy sail trainers, and interestingly, both with traditional drivetrains rather than sail-drives. A lot of institutional mechanical know-how went into the decision, and reliability and repairability certainly played a roll. The same block can be turbo-charged for more horsepower, but the idea was nixed over concerns about added complexity, fuel consumption, range, and the irrationality of pushing a displacement vessel past hull speed.

The mission also drove tankage selection, and with a coastal itinerary being the mainstay of vessel usage, the chance to pull in and top-off lessened the need to lug lots of liquid. A 50-gallon holding tank was deemed necessary and a 130-gallon potable water supply was there just in case a Bermuda run might come into play. The scan’t 50 gallons of diesel are consistent with the idea that cadets will have no shortage of opportunities to motor from port-to-port during their training on other vessels.

Under sail

One of the biggest departures from the Navy 44 is the L44’s carbon-fiber spar and fractional rig, as much a commitment to new technology as to simplifying sail handling. The mainsail has no full battens, only partials. As many racers have found, full battens on a boat with a permanent backstay can be a nuisance and rob performance in light air. The lower two battens are parallel to the boom so reefs 1, 2, and 3 can be easily tucked in, and the bunt of sail beneath the reef-point can be gathered and tied in a simple process.

The relatively small working jib is functional in a 10- to 30-knot wind range and allows the cadets to forego the foredeck two-step of sail changing as a thunderstorm rolls through at 0300. This fractional rig does require the crew to be ready to reef the large mainsail, but with good hardware and proper crew technique, it is simple to accomplish once the crew has learned the all-important lesson of not waiting too long to tuck in a reef.

The new boat comes with a conventional spinnaker, and with a crew of agile youth on board and light wind in play, there’s good reason to run spinnaker gymnastics training. We are sure that the civilian cruising version would also offer an asymmetric option with some form of removable sprit just in case your crew isn’t comprised of a half-dozen 18- to 21-year-olds.

Underway, the Leadership 44 delivers, pointing high and footing fast. One of the value-added fringe benefits of the fractional rig is that the boat will sail to weather when reefed with just the mainsail up. Another big plus is that the small jib and large mainsail combo fits a wide range of wind speeds without the need for a sail change.

Conclusion

The main saloon in a sailboat doesn’t need powerboat sofas to sell. And if you are planning a lot of overnight passages, it makes sense to have at least a couple berths amidships where dorade vents keep the boat ventilated and the pitching motion found in a seaway is reduced. The same goes for a galley that has sinks that drain on either tack and a stove that has room to swing through a 40-degree arc, even when the boat is already heeled 15 degrees to leeward.

In short, we like the Leadership 44 because it’s a boat to be sailed and savored during a passage rather than one that has to be endured.

Morris has plans to build two civilian versions, a racer and a performance cruiser. Draft and interior options vary, but the same quality of build and attention to detail found in the L44 will apply. The cost of these semi-custom boats is in keeping with other boats in the Morris line, and for those looking for more pure sailboat than fashion statement, it is a very valid alternative.

Very nice, but this is the taxpayers money and personally, I see no justification for a $1.2M expense over a high quality semi customized production boat of $400-500K.

Catalina 440, for example, could meet the specs really well and for sure, the builder could add/customize anything necessary.

Training USCG mariners isn’t racing, it is seamanship and sailboat handling in different real world conditions.

Nitzan Sneh

s/v GDY-Kids

Contest 43

Boston, MA