Photos by Joe Minick

Editors note: PS contributor Joe Minick is currently long-distance cruising with his wife Lee aboard their cutter-rigged Mason 43, Southern Cross. In September 2011, the boat was significantly damaged during a major storm while anchored in Vliho Bay, off the Greek island of Lefkas. The boat was knocked down multiple times during the gale, taking on a flood of water through the offset companionway, and took a beating when it collided with two neighboring boats. Having just completed a year-long refit, the couple and Southern Cross are heading for Malta and Tunisia next.

For details on the Vliho Bay storm, the resulting damage, and the Minicks lessons learned, see Part 1 of this report in the April 2013 issue.

When a storm, packing gale-force winds with gusts to 115 knots and torrential rain left our Mason 43, Southern Cross, in shambles off the island of Lefkas, we sought assistance from our insurance company.

Our insurer, Pantaenius UK, immediately dispatched a claims agent to assess the damage and a surveyor to monitor and assist in the repair process. The boats gear casualty list was long, and the extensive damage to the boat included the hull, deck hardware, and our electrical systems, which had been flooded in the knockdown. Thanks to our surveyor, Spiros Courtelesiss expertise and knowledge, we found a marina that could complete all our necessary repairs: Gouvia Marina on Corfu, about 24 hours sailing to the north of Lefkas.

For cruisers in the far-flung corners of the world, successfully carrying out such a sizable refit can be challenging, even with the help of a knowledgeable surveyor and a reputable insurance company. We had many ups and downs through Southern Crosss refit, but after nearly a year on the hard, the mission was complete. The boat sported new systems and hardware, and we gained first-hand knowledge about insurance policies and claims, and how to tackle extensive repairs far from home.

First Things First

In the October 2012 issue, Practical Sailor offered an in-depth look at marine insurance. Check out A Sailors Guide to Marine Insurance, along with some tips on ways to save money on your policy and a rundown of recent changes to marine insurance underwriting. You can also find these articles posted with this story online at www.practical-sailor.com.

Selecting an insurance company is every bit as important as choosing the coverage that best matches your cruising plans. Its equally crucial to understand how any potential disaster would be handled, especially in a foreign country, and why the insurance provider may impose requirements of its own.

Our insurance policy is termed a yacht policy with the following provisions: agreed fixed value for the hull, including inventory, equipment, engine, and dinghy; third party liability with single limit for personal injury and/or property damage; uninsured boater, including medical payments; towing; salvage; and fuel and other spills. We do not carry hurricane haulout coverage as our current sailing area does not include hurricane zones. Like many other international cruisers, we also chose not to have medical payment coverage; instead we carry health insurance that provides international coverage.

Up front, you should realize that the company is closely bound to the terms of your policy, just as you are. The representatives handling your claim don’t have the power to re-interpret the policy, so expect them to stick closely to the terms as they are laid out in it.

Our London-based Pantaenious claims agent, Felix Evans, was always courteous and more than helpful during the many email and phone conversations we had during the course of the refit. Both he and Courtelesis repeatedly proved to be true professionals.

You should also be aware that fraudulent insurance claims abound, and these folks have pretty much seen it all. Although its unfortunate, understanding their concerns in this area will give you insight into the claims process and help smooth the way ahead.

Making accurate and complete documentation will be a big part of your job, and doing it well will go a long way toward establishing a good relationship with the insurer. This should include invoices complete with local taxes, shipping, and related expenses plus photographs. The surveyor will also document much of the repair project with photos, but in the preliminary stages, when you are documenting items you will replace, pictures help everyone involved to understand what is needed.

Prior Approval

Almost all marine insurance policies contain a clause requiring you to obtain approval before a repair is made or a replacement part purchased. This means that the claims agent and surveyor assigned to your case will, to some extent, govern how your repairs proceed. You will still be involved in selecting who will make the repairs and how they will be done, but at every step of the way, you likely will need the approval of the claims agent and/or surveyor before proceeding.

This can be a bit of a hassle, but often, it can be to your advantage, too. Your local surveyor can help by recommending competent local repair facilities and steer you to available local sources of replacement parts. You can always shop around and make your own choices, but ultimately, prior approval will almost always be required, unless you are willing to shoulder the expense on your own.

Understanding Fine Print

From the very beginning, familiarizing yourself with the terms of the policy is a must. We had a lot to learn about our situation, and it really needed to start with a thorough reading of the policy we had purchased years before. Not all insurance policies are the same, but many contain similar clauses that require certain actions on the part of the owner.

Beyond notifying the insurer of any boat damage as soon as possible, owners are frequently charged with doing what is reasonably possible to limit further loss or damage after a disaster occurs. This doesn’t mean that you must take undue risks, and it certainly doesn’t preclude you from seeking medical attention as needed, it simply asks that you take what steps you can to secure the boat, even if it means hiring outside help. Typically, the owner will be reimbursed for any reasonable expense incurred in this process. This is usually the one exception to requiring prior approval before acting, but it must meet the test of reasonableness, in any case.

Other provisions of a typical marine policy will spell out exactly what will be reimbursed and how. One common clause states that if damaged equipment must be replaced, the owner will pay something like 30 percent of the cost, if the gear was more than 10 years old. For some items-dinghies and outboards, for example-the time period may be much shorter. Sometimes referred to as the New for Old clause, this percentage may be applied to any shipping or duty that may also be incurred as well as parts needed to repair installed equipment. Often, no consideration will be given to claims that the original was in like-new condition before the incident, but this clause isn’t usually applied to labor costs or repairs to the hull itself.

Southern Crosss 12-year-old Monitor windvane, which disappeared during the storm off Lefkas, was replaced under this clause, and the fact that a stainless windvane doesn’t deteriorate much with age was immaterial in the view of the insurer. Still, it is exactly what the policy stated would be done, and we agreed to this when we purchased it.

If your boat is more than 10 years old, what is not immediately obvious is that installation of any equipment less than 10 years old will probably have to be documented before it will be exempted from the New for Old clause, if it must be replaced. A purchase receipt or invoice is customarily required, but unfortunately for us, all of our records were destroyed by the flooding during the knockdown. All that survived were our maintenance logs where the installation of new equipment was recorded. Ultimately, Pantaenius did graciously accept this somewhat limited form of proof of purchase, but you cannot count on this in every case. Duplicates stored on shore would be a better approach.

Another typical provision states that where possible, repairs to the finish of the hull and deck will be done only in the area where the actual damage occurred. This can be worded in several ways, but it basically means that scratches or repairs to a section of the hull or deck may be spot painted or refinished. The insurance company is not responsible for loss in aesthetics if the original finish cannot be matched perfectly. Owners can request that the entire area be repainted, but they will often bear the additional expense themselves. The same exemption is frequently applied to localized repairs that could conceivably affect overall sailing performance.

In this same vein, there is frequently a provision that addresses the replacement of related equipment. For example, a damaged battery monitor that controls an inverter/charger may be obsolete or out of production. The loss of the battery monitor renders the inverter/charger useless, but it was otherwise undamaged. Under this policy provision, the owner will be reimbursed for a suitable replacement battery monitor, but the insurance company is not responsible for the other system components that are no longer usable as a result of substitution.

Our particular policy set a limit on the amount the insurance company would pay for damage or loss of onboard personal possessions (anything not attached to the boat). If youre a liveaboard cruiser, consider this limit carefully when purchasing a policy. It can usually be increased for an additional fee, which in hindsight, we would have paid. Virtually everything we own was aboard Southern Cross, and the loss of three computers and some high-priced camera gear put us over the top of the pre-set cap.

Far From Home

Being far from your home waters when disaster strikes complicates things a bit. Some may advise you to just go home and let the insurance company handle your boats refit, but this is seldom in your best interest.

To begin with, the boats owner is usually the person most familiar with the boat and its myriad systems. Being on hand to consult with those who will actually do the repair work can be a big plus, especially if you are short on drawings and schematics detailing how things were installed. If you are unwilling to settle for someone elses opinion of how things should be done aboard your boat, you should be there.

Then there is always the matter of trust. In other parts of the world, things are often done quite differently than the way you would expect in the U.S. The insurance surveyor will attempt to provide some level of oversight during the repair process, but he will most certainly have many jobs to keep track of and can’t be everywhere all time.

I have seen many instances where a boat owner went home for an extended period and returned to find that work contracted for while he was away was not completed or was done incorrectly. If you arent there when decisions have to be made, someone else will make them for you, and this is where many problems begin. If you must leave, you take a gamble on the level of trust available; if possible, hire someone you know you can trust who is capable of supervising the work.

Another reason is purely financial. The insurance company will probably be unwilling to directly pay for any repairs, parts, or services along the way. This means that you will need to make arrangements to pay for advance deposits, completed repairs, orders for replacement parts, and all manner of expenses as they occur during the repair process. If payment isn’t made, work usually stops until you return, and frankly, its often a mistake to assume that anyone will let you know when this happens.

The other side of the financial coin is that in many parts of the world, credit cards are frequently not accepted, and cash payments and bank transfers are required to be in the local currency.

This presents a problem for American boats abroad. Bank transfers can be done between U.S and foreign banks, but they can be problematic and take several days. Your bank may be able to convert U.S. dollars to the required currency before sending it, but a service fee will be added to the already pricey transaction fee, and you will need substantial documentation to make the transfer, including addresses, bank names, account names and numbers, all of which must be precisely accurate.

When deciding to remain with the boat during repairs, its also important to familiarize yourself with local regulations that govern extended stays for both the boat and its crew, as each may be treated differently. After much discussion with authorities and the local marina, we thought we had met all the requirements when we surrendered our transit log, which is issued to foreign vessels in Greek waters, to the local customs authority. Our understanding was that this would allow the boat to remain in Greece past the normal expiration date shown on the transit log. We the crew, would still need to exit the country after 90 days and remain away for a like period, but the boat would be allowed to stay.

When repairs were nearly complete, we went to reclaim the transit log only to receive a loud and lengthy dressing down for having allowed the transit log to expire, even though it was in their custody. After all the shouting was over, we were granted a short extension with instructions to leave the country with the boat before it expired again and not return for at least 90 days. (Perhaps we didnt have such a good understanding after all.)

Getting the Work Done

Another argument for your continued presence is the possibility that you may decide to do some of the work yourself. This is almost always acceptable to the insurance company, but don’t expect to be compensated for your efforts.

We chose this approach and rented a small apartment within walking distance of the Corfu boatyard. We had done most of the original wiring and system installations on the boat, so our original plan was to handle all the electrical repairs ourselves while others worked on the hull, on-deck stainless, and teak repairs. Unfortunately, we ran into difficulties almost immediately.

Many replacement parts had to be ordered from other countries at considerable expense and with all the aforementioned problems of making payments. Devices compatible only with 115-volts AC shorepower, those supplied in Imperial/American dimensions or mated with National Pipe Thread (NPT) are usually available only in North America. Our best solution entailed returning to the U.S., purchasing everything required, repackaging it all into the fewest number of boxes possible, and shipping them to ourselves on the island of Corfu. But even this proved to be more difficult than anticipated.

We arranged for an agent to accept the shipment in Corfu and handle the complicated process of clearing everything into the country. However, the entire shipment was intercepted in Athens, and we were given three days to pay the customs duties, the 23-percent Value Added Tax (VAT), and local agent fees, or the shipment would be sent back, at our expense. The Yacht-in-Transit provisions that usually allow foreign vessels to avoid paying the VAT were suddenly no longer available, and only bank transfers in the local currency were acceptable. Numerous copies of various documents had to be faxed to Athens, and eventually everything was finally delivered to us in Corfu-but it was an expensive learning experience.

Many things did go well during Southern Crosss refit. Local restrictions prevented spraying the hull outdoors, and there wasnt room enough to build a tent around the boat, but local painter Spiros Koutagair did an amazing job of painting one side of the hull and the transom with a roller and a brush. Its almost impossible to tell the difference between the previously sprayed and the hand-painted areas, in spite of the poor weather conditions for painting that spring.

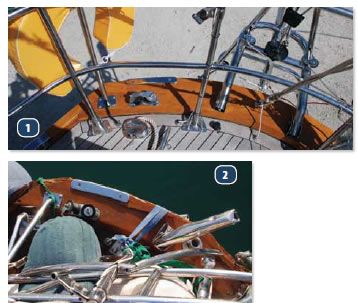

Corfu is popular with folks from the UK, and an English ships carpenter (Dean MacMahon) living there did exceptional work on the teak repairs, while a skilled welder (Martin Crozier) originally from the Newcastle shipyards replaced almost of the stainless hardware on deck with mirror images of the originals. Exceptional craftsman, both MacMahon and Crozier have their own companies but work in Gouvia Marina.

Conclusion

Successful recovery from any type of nautical disaster depends on many factors, including the extent of the damage, the provisions of your insurance policy, your location, and your own ability to cope with what must be done.

When all was said and done, we ended up paying slightly less than 10 percent of the total cost (which was a big number) of the refit, not including our own labor and expenses. This was due in no small part to having an excellent insurance company with staff that were both polite and reasonable far beyond expectations.

We were fortunate to have survived the storm with no major physical injuries. Other cruisers were not, and had to deal with obtaining medical treatment and recuperation on top of everything else. If possible, its a good idea to include medical payment coverage in your boat insurance policy; with it, the insurer will cover medical expenses (up to a defined limit) that result from a boat-related accident.

Some fellow storm survivors found themselves in a situation where the cost of the repairs exceeded the value that the boat was insured for, and how the loss was handled depended on what type of hull coverage they carried: actual cash value and agreed-on value. Actual cash value policies determine the value of a boat based on the age and condition at the time of loss as determined by the underwriter, using the NADA guides (www.nadaguides.com), the BUC Used Boat Guide (www.bucvalu.com), or other resources. Agreed value policies are agreed upon by both the owner and insurance underwriter at the time the policy is purchased. This, in our opinion, is a better choice.

In some of the Vliho Bay cases, the owners were paid an amount equal to the insured value of the boat while retaining ownership of the boat. In others, handing over a check for the insured value of the boat, the insurance company claimed title to the boat. As the owner, you can often buy back the boat for the salvage value and make your own repairs, but in either case, it may be impractical to attempt a project of this magnitude, and the boat ends up being sold as is or becomes the property of the insurance company.

Not much can be done to forestall this sort of outcome except to keep the insured value of your boat at the maximum allowed, and as is often said, keep the water on the outside.