Nearly everyone involved in the boating industry during the prosperity of the 1970s also has a vivid recollection of the 1980s, when the industry stood on the brink of implosion. Old-line builders like ODay, Cal, Ericson and Pearson went the way of T-Rex; others endured losses for several years before returning to profitability in the mid-1990s. A sad by-product of that debacle is that molds for three of the finest boats produced on the West Coast are gathering dust in a boatyard in Port Townsend, a storage shed in the San Francisco Bay area, and a warehouse in southern California.

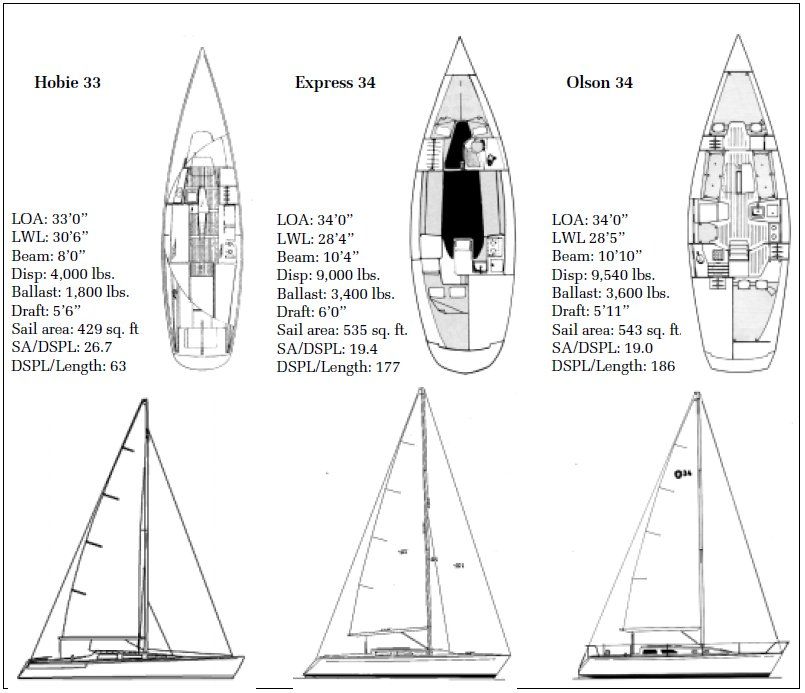

Compared to conventional productions boats of the mid-1980s, the Express 34 and Olson 34 were lighter and faster, but still suitable for distance cruising. The Hobie 33, though most suitable for camper-crusing, was designed to be fast yet trailerable and capable of blue-water sailing. Nearly 20 years after their short-lived production runs, the three are still so popular that finding a used one can be a challenge.

The Designs

The Express 34 was the third Carl Schumacher design produced by Alsberg Brothers Boatworks in Santa Cruz. Schumacher designs have been afloat since the 1970s, ranging in size from 10 to 70 feet. Among Schumachers early designs, his quarter-tonner Summertime Dream won the North American Championships in 1979 and 1980. A current design, the Alerion Express, is one of the sweetest sailing, smartest looking boats weve seen in the last 10 years.

Terry Alsberg, who managed the company, was a graduate of Ron Moores boatbuilding shop, adherents to Bill Lees fast is fun slogan. The company made its first splash in 1984 with the introduction of the Express 27, a pocket racer that enjoyed great success in one-design and MORC competition. Many of the 117 produced are still racing.

The Express 37, a true performance cruiser, was launched in 1984, and 65 were built.

Profits from the sale of the 37 were used to fund the tooling for the Express 34, which was launched in 1986. Though it received Sailing World s Boat of the Year Award, its cost led to the eventual demise of the company.

Brokers told us that we needed to have more accommodations belowdecks than the 37 – cruiser add- ons that increased the price, remembers Schumacher. We ended up with a lot of Express 37 features in a 34-foot boat.

Since it was easy to use the same raw materials as were used on the Express 37, the laminates became heavier, and more expensive. The final boat was about 1,000 pounds heavier than my design, Schumacher adds. Boat were priced at $80,000, only $15,000 less than the 37.

Eventually, faced with high production costs, a softening market, and poor financial planning, the company closed its doors in 1988.

Also located in Santa Cruz, Olson Yachts produced five different models under its banner from 1978 to 1986, and the Soverel 33 for a different company.

The most famous of George Olsons designs is the Olson 30, of which 350 were sold. A proven race winner, the Olson 30 is still active in onedesign fleets in many major sailing ports.

In response to a market craving a MORC racer with a modicum of creature comforts, the company also produced 250 25-footers.

Of the 34s genesis, Olson says, We then decided that the 34 would fill a niche for a larger racer- cruiser, we wanted a light to mediweight boat that was easy to sail, would appeal to racers, and double as a family boat. The design featured a moderately angled reverse transom, and elliptical keel and rudder.

Shortly after producing hull #1, however, the company ran into financial trouble and the tooling was sold to Ericson Yachts.

Don Kohlmann, then directing of marketing for Ericson, says We added the Olson to our product line because we wanted a faster, lower-priced boat than the Ericson 35, a cruiser priced $22,000 higher than the Olson.

Ericson Yachts produced 37 Olson 34s, which were priced at $60,000, including sails.

The Hobie 33 was designed by Hobie Alter during the final monthsof his boatbuilding career.

An avid southern California surfer, Alter captured the surfboard market in his teens with the development of lighter, stronger boards. He followed with development of the 14- and 16-foot Hobie one-design catamarans, two of the largest selling boats in industry history.

Eventually selling to the Coleman Company, Alter retained an office and began work on the prototype for his first monohull. Following a pattern of designing easily transported vessels, he produced a strong, fast, 33-footer that, he says, could be launched by my daughter. She was the guinea pig. A video produced by his pal Warren Miller, of ski movie fame, shows the prototype being driven onto a seawall with no damage to hull or keel. The combination of an easily retractable keel and 8 foot beam allowed trailering on any state or federal highway.

The boat was ultimately doomed by a $50,000 price tag and a downturn in the industry. According to Alter, another contributor to the boats demise was its development in a nonmarine, bureaucratic environment, He describes management meetings where I was typically not talking with boat people, but with marketing and accounting types.

The boat was a stepchild for the company, and the retractable keel was expensive to produce. The company eventually built the last boats with a fixed keel.

One Hobie 33 buyer was Dennis Conner, who, says Alter, bought two, stretched them to 37 feet, and used them as prototypes for an Americas Cup boat with a double rudder system.

The boat was in construction from 1982-1986, and 187 were sold; theyre being sailed on all coasts of the continent, and even in Nova Scotia. Theyre especially popular with lake sailors.

Accommodations

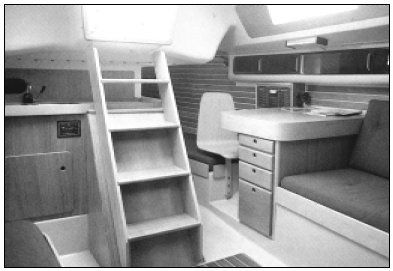

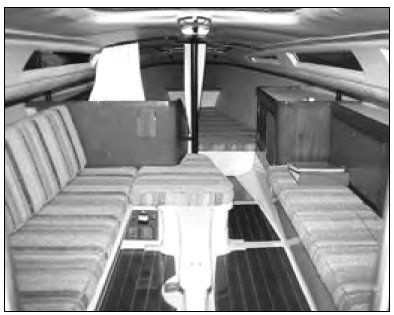

The Olson and Express have legitimate cruising interiors, though the Express exudes a racing pedigree.

Freeboard on the Olson is 1 greater than the Express, which creates more interior volume. Headroom is 64″, compared to 61 in the Express.

In his introduction of the boat, Olson said he intended to provide family-oriented accommodations for six adults, with pressurized fresh water, a two burner stove-oven combination, and large ice box with refrigeration as an option. Bulkheads are teak veneer; joinery trim and cabinetry are solid teak.

Olson owners give the interior high marks because it features a head located aft to port, adjacent to an enclosed stateroom with a double berth. Berths in the Olson 34 measure 66″ in the bow and stern; settees amidships measure 62″.

The galley is to starboard, opposite a functional nav station that faces forward. A drop-leaf table in the center of the main saloon provides comfortable seating for 4 to 6 adults.

The configuration of the Express is similar, though owners say a mast concealed in the head is a plus.

Sleeping quarters for six are in berths measuring 66′ in bow and stern, and settees amidships measuring 64″. Schumacher discovered on an ocean passage that the middle berths are two inches shorter than his design.

As with the 37, the foundation for the V-berth is a fiberglass molding with non-skid so that, with the cushions out, it makes it possible to help the foredeck crew handle sails from down below, he says.

Aft of the V-berth is a hanging locker to port, and head with a shower to starboard. The saloon is furnished with a table that folds off the main bulkhead. The chart table/nav station is to port, the galley to starboard.

A second double berth is located in the port quarter.

By comparison, the Hobie interior reflects the designers intent to trade creature comforts for a trailerable yacht with an 8-foot beam. The interior consists of a narrow area with only 410″ headroom, so performing calisthenics belowdecks is not an option.

Nonetheless, the designer creatively provided space for amenities necessary for overnighting. The V- berth is situated forward of a half- height bulkhead, and enclosed by a privacy curtain; the berth is 6 feet long and wide enough for two adults. A small space is designated for a porta-potty.Settees provide seating amidships at a table that mounts atop the keel trunk.

An optional two-burner stove is mounted on the inside of a cabinet door. One owner cleverly constructed a mount for a gimbaled butane stove that fits into the channels for the companionway slats. That way we can eat and cook in the cockpit and belowdecks at the same time, he said.

An ice chest at the companionway doubles as a step.

The mature sailor will find accommodations in the Express and Olson more comfortable for distance racing and cruising than the Hobie, which resembles a floating campsite.

Deck Layout

Though original deck layouts may have undergone modifications, all three boats were originally rigged for racing. Deck hardware was provided by name-brand manufacturers like Lewmar and Harken, the exception being custom fittings designed and constructed by Hobie.

The Hobie has a single-spreader rig measuring 354″, the others double spreader rigs. The Olson was produced in two versions; a tall rig designed for light-air sailing is 3 1/2 feet taller than the standard 373″ section. The Express 34 mast is 386″ tall. Wire rigging was the standard on all three boats. Many owners report that the original equipment has not lost its integrity; others have replaced wire with rod rigging. The Olson and Express were equipped with hydraulic backstay adjusters.

Cockpits in the Express and Olson are larger and more user-friendly than the Hobie, especially with a crew of 6 to 8 in racing trim. A common complaint among Hobie owners is that the cockpit seats are too narrow, forcing us to sit on the coaming, which also is too narrow.

Construction

Except for Schumachers meticulous records, exact details of construction schedules have disappeared. Though all of the boats were designed with speed and the PHRF handicap rule in mind, they also were built to sail in stiff breezes and ocean conditions common to the West Coast. Consequently, owners say, hulls, decks, and rigs of 15- to 20-year-old boats have the same structural integrity as when they rolled off the production line.

According to Schumacher, the Express 34s outer laminate consists of 3/4-ounce mat, two layers of 18-ounce co-fab, and 3/4-ounce mat bonded to 3/4-inch thick end-grain balsa, with 18-ounce co-fab on the inside. The deck is similar, except that 3/4-inch balsa core was in the lamination, and unidirectional reinforcements were on the house top and foredeck.

The interior consists of a structural grid with bulkheads bonded into the structure with 18-ounce roving.

Company literature provides a general description of the Olson 34 layup: a one-piece monocoque hull consisted of mat, 18-ounce bi-directional glass and roving, with extra laminate in high-stress areas. Beams constructed of unidirectional roving and woven roving were laminated to reinforce the hull and distribute loads from keel, mast, and engine. Bulkheads and berth tops were bonded to the hull with fiberglass. The original schedule called for a cored hull and deck, however only hull #1 followed that schedule.

Following the sale to Ericson, says Kohlmann, We constructed hulls of hand-laid fiberglass, which produced a heavier boat than designed.

Decks were cored with marinegrade balsa, which one owner described as excellent for mounting gear. Ive never worried about the core compressing when mounting deck hardware.

Hobie Alters recollection is that the Hobie 33 hulls were laid up with alternating layers of fiberglass around a 3/4-inch urethane foam coring.

Considering the industrys historic inability to prevent osmotic blisters, its surprising that the Olson 34 was sold with a five-year guarantee against blistering. Owners of Express and Hobie yachts report few blistering problems. One owner said his blistering required a few bucks and aweekend of sanding and filling.

Performance

All three boats receive high marks from owners who sail them in the ocean, on both coasts, around the buoys, and on lakes. Since they share a common handicap in many areas, the trio frequently goes head to head on the race course.

Bruce Nesbit, who raced his Olson 34 from San Francisco to Hawaii in the Singlehanded TransPac, managed the passage in 13 days, 18 hours. He finished second in his division, fourth overall.

I had the wind on the nose for two days, cracked off and set the spinnaker on day three, then switched to a reefed main and double headsails, he says. Winds were around 15 knots until the last five days, when they piped up into the 20s.

With that sail configuration the Autohelm steered the boat, and I averaged 10 knots for one 24-hour period. It was easy.

Olson owners say the boat performs best in windspeeds below 15 knots, and sails surprisingly well in 5 knots of breeze. The Express is faster on all points of sail in more than 20 knots of wind, one Olson owner says.

However, when sailing to weather the Express must be kept on her feet with bodies on the windward rail, or reduced sail.

It takes a good main trimmer to balance the boat, or the helm will load up, says one owner, a former 505 dinghy racer.

Shes stable off the breeze, as well, and shows good motion in heavy seas, partially because of her large rudder, adds a racer from San Francisco.

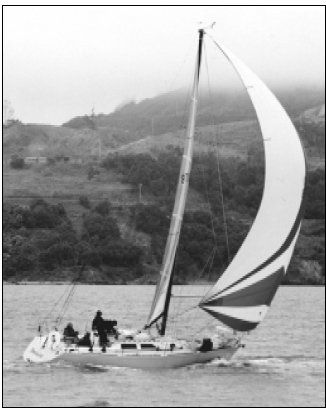

Because she displaces only 4,000 pounds, 1,800 in a bulbed keel, the Hobie suffers when sailing to weather in a chop. Mountain lake sailors rate her an A-plus sailing on flat water, and shes a screamer on a close reach.

Shes tender, but with a full crew on the rail and balanced traveler, she is well-mannered, one owner says.

It took a long time to learn to feather the main when sailing to weather, a veteran racer says. Do that and shell squirt uphill. I used to sail with a reef in the main, and the #2 jib. Now I sail with a full main and #4. In heavy winds we simply ease the main.

Express and Olson owners agree that off the wind in a blow the Hobie will leave them in her wake.

The harder it blows, the better she likes it, says a Hobie owner who completed the 380-mile San Francisco- Santa Barbara race in 35 hours. We hit 25 knots on the speedo. The only boat that beat us to the finish was a J- 130. Plus, I can singlehand it on an ocean race, or take my stepdaughter on a day-sail.

Conclusions

The common denominators of these three boats are curb appeal, performance, strong hulls, good rigging and good deck gear. The Olson and Express have an advantage sailing to weather, and more comfortable accommodations. By comparison, the Hobie will be 8-10 knots faster on a downwind reach, is trailerable, and costs half as much as the competition.

The Olson and Express sell for 85% to 90% of their original price; the Olson in the mid-$50,000 range, the Express from $60,000-$80,000. A barebones Hobie sells for $13,000-$15,000; however, add the cost of new sails, a trailer, and an 8-10 horsepower outboard, and the price jumps to between $22,000 and $25,000.

Its too bad more of these all-around performers werent built.

On the Hobie 33

Weve withstood 45-50 knots on the nose for 8 hours in a large seaway – 12-20 foot waves. Not fun, but not dangerous.

– Owner, Nova Scotia

Unlike some boats, the bow comes up out of a wave. But it will heel. Downsize sails early.

– Owner, Northern California

Took 12-15 foot seas from Bahamas to Florida. Fifty miles in three hours. No problems!

-Owner, Florida

The motor retracts into a transom well, with a hull plug that drops into place to reduce underwater drag.

-Owner, Austin, Texas

The flat bottom tends to pound in heavy seas.

-Owner, Chesapeake

On the Express 34

This is a lot of boat in a small package. I find her easy to doublehand but at times a handful. Ive had this boat going as fast as 19 knots surfing outside the Golden Gate.

-Owner, Santa Cruz

If you want a boat that is cleverly laid out and very functional this is the boat for you. However, its not fancy, and the head and galley are small. With its nicely shaped and large rudder (elliptical) you always feel in control.

-Owner, Sacramento

We lived aboard for 18 months and enjoyed our time there.

-Owner, Los Angeles

My wife loved the interior. Performance was my main deciding factor.

-Owner, San Francisco

On the Olson 34

I have a friend who has an Express 34. We used to moor right next to each other, so he sailed on my Olson 34, and I sailed on his Express 34. We concluded that: 1. If youre looking for a racing boat and don’t mind the open interior layout of the Express 34, its a faster boat-especially off the wind. Its noisier and rougher under power, but lighter and faster under sail. 2. If youre looking for a boat that you can cruise with two couples and still have a lot of fun on the race course, the Olson 34 is probably your best bet. The interior is nicer than the Express, and I especially like the aft head arrangement in the Olson. However, it does come at the cost of some sailing performance-especially off the wind.

-Owner, Portland, Oregon

I have crossed to Hawaii twice with this boat. We have carried spinnakers up to 30 kts of breeze with really good results after converting to a new Schumacher rudder and Harken bearings. The boat has landed on its side about three times and come out unscathed. The deeper rudder and new bearings improve the boat control in a big following sea.

-Owner, San Francisco

They put in a double sink to attract the ladies. Not good because you need more counter space. I put in a single sink. They advertised the boat as having a 30-gallon water tank, but it was really 20 gallons.

-Owner, Los Angeles

My wife and I sailed from Hawaii to San Francisco in 19 days and motored for only 20 hours. The rest of the time the boat sailed herself. The vane steered while we played dominoes.

-Owner, San Francisco