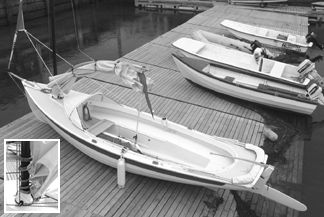

Ordinarily, the boats we review in these pages require a substantial investment, something like remortgaging the house. But on occasion, we get around to examining smaller boats, the kind that you can get underway with little time and fuss, and nominal expense. We like boats like this. These craft usually require little maintenance, are user-friendly, economical, and frankly, practical. That’s in part why we took note of the new Norseman 17.5.

Whether you’re stepping up from a sea kayak or down from an auxiliary cruiser, this unique 17-1/2-footer is a boat to look at. And her looks set her apart. She’s attractive, proportionate, and salty. Her wishbone gaff is curvaceous; her stubby bow-sprit is saucy, and her sprung sheer and serious stem and stern angles all invite the eye. The Norseboat 17.5, however, is about more than appearances.

Builder Kevin Jeffrey calls her “a ticket to adventure.” That’s a pretty good description of sailboats in general, but Jeffrey is talking about a sort of self-sufficient, energy-pinching challenge that isn’t necessarily the norm in your average marina. A mechanical engineer, the Norseboat’s creator has operated Avalon House for over 25 years in the business of solar home design, renewable energy research, applied marine electronics, and organic food distribution. He has also explored (with his wife and twin sons aboard various cruising catamarans) much of the area between Cape Cod and the Dominican Republic. In June of 2003 he incorporated Norseboat, a separate company, to build boats on Prince Edward Island, Canada. “I envisioned a small, lightweight, low-maintenance sailing and rowing boat that would be easily trailerable,” explained Jeffrey.

After brainstorming, cogitating, experimenting, and consulting with small-boat gurus, sailmakers, and cruisers, Jeffrey took his concept to Chuck Paine of Camden, ME. Paine’s reputation for good-looking, sweet-sailing designs has made him one of the most sought-after naval architects in the world, but, as the designer himself points out, it is very rare that a small-boat builder seeks (or can afford) his expertise. “To do what we wanted with this boat, I knew I had to get it right: from looks to performance to seaworthiness to handling. That’s why I went to Chuck, and I’m happy that I did,” Jeffrey said.

We sailed (and rowed) this craft on a glorious, sunny day in the Florida Keys. We spent several hours under all modes of power (including the screecher, but excepting the optional electric trolling motor). We didn’t nose her into the Gulf Stream, nor spend the night beneath her cockpit tent, but despite the occasional distracting hail from mullet fishermen and circumnavigators—complimenting and questioning us as we passed—we believe we got a good feel for most aspects of this multi-faceted skiff.

Design

“To begin,” Jeffrey explained, “she’s a marriage of traditional and modern. The solar houses that I’ve designed use all of the energy-management technology available, but as you drive up to them you’d think they’d been there for a hundred years or more. This boat comes from the same places.”

To wit, the Norseboat has a carbon-fiber mast. All up, she weighs just 400 pounds. She’s a composite of epoxy-based resins and top-grade glass fibers. At the plant on Prince Edward Island, the 17.5s are assembled of component parts that are molded in a resin-infusion process by a subcontractor. It’s instructive that it took an additional two months of daily fairing, polishing, and tweaking before the original plug was ready to make the hull mold. The boat has integral positive flotation and is laid up to American Boat and Yacht Council standards. Her spray hood and bimini are yacht quality. She evinces no exterior wood and sports Harken hardware. And yet there’s something very traditional about her.

“Her pedigree,” Jeffrey asserted, “stretches back for centuries. Open boats have, of course, been around forever, but I had in my mind an ideal—something like the Sea Bright skiff.”

Legendary for handling surf and big payloads the Sea Brights are lapstrake fishing skiffs that came into prominence beginning in the 1840s. The abundance of market fish off the New Jersey Coast and the growing appetite for them in New York City prompted development of rugged dories that could be launched from the New Jersey beaches. They have long been appreciated for their toughness and function, but they are equally celebrated for their grace and simplicity. Shaped by generations of launchings through the breakers near Sandy Hook, these boats evolved into an archetype that, as one historian put it, “outfoxed the waves rather than overpowered them.” (Perhaps said historian was carried away by the achievement of Fox, a 16-foot adaptation of the Sea Bright skiff that made the first Transatlantic crossing under oars—55 days from the Battery to the Scilly Isles—in 1896).

Designer Paine told us: “The Norseboat was a very unusual project for us. In the process of developing the design, we looked at virtually all the relevant traditional models. Kevin’s respect for the Sea Bright skiff was our starting place, but from Whitehalls to Herreshoff tenders we tried to pick up what we could from the intuitive lessons learned by the people who produced rowing and sailing boats in the past. For instance, Nat Herreshoff always favored hollow bows. I can’t prove it to you scientifically, but they have also always seemed the most efficient solution to me. You’ll find hollow bows on most of my deep-keeled sailboats, and you see a similarly sharp, flared entry on the Norseboat.”

“Any boat involves compromise,” explained Jeffrey, “but as a boat to be rowed and sailed, the Norseboat had to resolve a major conflict. Light and narrow enough to be rowed enjoyably, she still had to be stable, mannerly, responsive, and fast under sail. We wanted her to be trailerable, but still at home in a seaway. We wanted her as light as possible, but we needed her to be capable of carrying an adult couple and their camper/cruising gear.”

Paine elaborated: “It was an involved project, but we never got far away from the basics. Water resistance impedes rowing. The Norseboat’s waterlines are hollowed somewhat to make her ‘slipperier.’ Dead weight was kept to a minimum with modern construction. Her lapstraked, molded form hull, for example, gives the boat tremendous fore and aft stiffness without the need for longitudinal stringers. Speed potential is allied to waterline length. This boat is long in the water. In an unballasted boat, stability comes primarily from the form of her center sections. Here we bumped out the archetype a bit in favor of increased waterline beam and the volume to create maximum displacement. Too little sail makes a boat doggy. Too much and she’s tender and cranky. We gave her a big (105 sq. ft.) mainsail but made it easily reefable. The screecher adds the horsepower to get the most from lighter airs and off-the-wind opportunities.”

The “wish-gaff” (the distinctive curved spar on which to hoist the Norseboat mainsail) was Jeffrey’s idea. “I don’t know where it came from, maybe the square-headed rigs the Dutch used,” he explained, “but I’ve had the shape in my mind for years.”

“I’ll say one thing,” added Mark Fitzgerald, the man in Paine’s office responsible for the Norseboat drawings, “it’s distinctive. I’ve never seen anything exactly like it. If you see a boat with a curved gaff you’ll know that it’s a Norseboat.”

The shape bears a remarkably close resemblance to the planform of the modern, high-speed sailboard. Wind tunnels have demonstrated that a narrow triangle at the top of a sailplan breeds “tip loss” when airflow slips over the windward side of the sail onto the low-pressure flow to leeward. While the gains may be minimal, adding efficiency to a sail, especially a loose-footed main like the Norseboat’s, is always a plus. No one would confuse the Norseboat with a record breaker, but her full-battened main (developed in conjunction with North Sails) seems a place where tradition and technical innovation have produced an elegantly performing, “better mousetrap.”

Paine understands maritime aesthetics. Form, function, shape, line, expectation, perception, color, and more go into it. It may be in the eye of the beholder, but few designers have been as consistently successful as he at delivering beauties rather than beasts. The Norseboat is another case in point. And, though everyone involved denies that it was intended, is it an accident that this surprising, far-ranging adventure cruiser, looks quite a bit like a diminutive Viking longship?

Deck Layout

Part of the boat’s ability to go where the water is deep comes from being partially-decked. Almost four feet of foredeck keeps what water that comes aboard from staying aboard as do six-inch sidedecks and a foot-wide quarterdeck. “Besides the protection this configuration gives you,” Paine explained, “you can sit on the deck to steer or hike, and that arrangement basically encourages people to sit where they should—in the middle of the boat. Trim is a critical variable in any small boat. And keeping crew weight as centered as possible helps make the Norseboat as safe and efficient as she can be.”

Jeffrey’s deep experience as a cruiser shows in the added protection that he’s incorporated. A dodger is unlikely on most dinghies. A bimini is certainly even more unexpected. Still this “explorer” has them both (as options). They are not only made to last, but they’ve been designed to work effectively, presenting minimal interference with sailing and rowing. Believe it or not, these items look like they belong on a 17-footer.

The sailing hardware is Harken. Here, too, adaptation of top-grade gear reflects intelligence and innovation without detracting from the boat’s simplicity. The mainsheet trims to a bail mounted on the centerboard trunk between the rowing thwarts. This minimizes twist adjustment, but it is conveniently central and allows the boat to be rowed with the rig in place and the sail furled between gaff and boom.

Performance

A Norseboat brochure states that she can be “carried to the water.” At a minimum of 400 pounds, that takes some toting. She’ll hardly be confused with your cartop kayak, but the accent on portability and convenience, however, is genuine. Stepping the two-part carbon fiber mast by hand is simple. So are the “systems” and moving parts. It’s typical of trailer-sailers to tout being “underway in less than 30 minutes.” With the Norseboat, you can better than cut that time in half.

With two rowers (an additional pair of oars costs $215 and there’s room to stow them), we estimated that we (along with our female coxswain) were making an easy four knots through smooth water. Much more pleasant to row than the prams and skiffs we’ve known, the Norseboat tracks and carries like a purpose-bred rowboat. “Some solo rowers have reported windage to be a problem, and chop is a pain,” Jeffrey allowed. Our universe is admittedly small, but as we bent our backs into the spruce we could see how rowing the Norseboat could be not only sustainable, but enjoyable.

To our eyes, the Norseboat’s mainsail looks small, but we were surprised at the boat’s response to it. Absent the intrusion of a handheld GPS, we were left to estimate our progress at better than half the true wind speed in eight knots. Once we set the tiny, roller-furling screecher, we made more of our own wind and our speed climbed to better than five knots or hull speed for a boat with a 15′, 7″ waterline.

With Practical Sailor at the controls Jeffrey seemed a bit nervous about stability as we hardened up and bore off around boats in the anchorage. From our position, though, those worries were groundless. Certainly a boat that’s narrow enough to row will not stand on her feet like a beamy cat or a ballasted keelboat, but the Norseboat presented no surprises and a pleasing amount of ultimate stiffness once she reached about 20 degrees of heel.

Our test sail was hardly exhaustive, and it’s hard to find exact parallels to this one-of-a-kind design. However, calling into memory catboats like Beetles and Marshalls, daysailers like the O’Day Daysailer, and decked-over dinghies like Snipes, our test boat measured up well. She accelerated admirably out of a tack, steered positively up and down, and was, in general, rewarding to steer and trim.

In the moderate breezes of our test sail, her helm seemed more neutral than expected. Perhaps this was due simply to having a small rig sited well forward. With minimal hull rocker, the 17.5 tracks well. Turning into the breeze was an issue, however. We felt the Norseboat lacked the “oomph” to drive through a tack (at least as consistently and well as any of the comparable boats mentioned before). Sailing her full and footing to gain speed before tacking (similar to multihull practice) is a technique that we should have tried, but didn’t. Adding a working jib would be another solution; and Jeffrey is considering that option.

“Of all the things this boat can do, we want her to do them well. Of all the things she does well, she should be, first and foremost, a good sailing boat,” said the builder. He has come close to that ideal in a number of ways. Joy in sailing, maximizing light airs, and creditable weatherliness—all of those targets have been hit. When you factor in the ease and pleasure of rowing the Norseboat, those accomplishments look even better. However, to the extent that a light or neutral helm mars performance, and a long keel makes vessels somewhat stubborn to turn, she falls a bit short of her performance potential.

Conclusions

The excitement surrounding this boat is exceptional. Boat show passersby appeared to stop, linger, and admire the boat. That’s not surprising. The Norseboat 17.5 has an unusual mien due in part to her exceptional versatility. And with a $12,495 price tag (base boat), a majority of show goers might readily see themselves at the helm.

Somewhat akin to the shimmering ideal of a boat that can star at both racing and cruising, the formula of a magic blend of tradition and innovation” has been around the waterfront since probably long before the Vikings. We think the Norseboat 17.5 gives it legitimacy.

The shortfalls that we experienced in sailing her are small, and curable. But the vision she opens up of creative and rewarding voyages that are affordable, of adventures that depend only on having a trailer hitch and the weekend off, of the capacity to enjoy “organic” recreation under sail and oar, is huge and happy.

Contact – Norseboat Ltd., 902/659-2790, www.norseboat.com.

Also With This Article

“Norseboat 17.5 in Context”

“Construction”