If you think your boat is a bear to maintain, you might take some consolation in this months used-boat review of the Union 36. It is a fiberglass boat, but considering the amount of teak on deck and belowdecks, it might as well be made of wood. Not that there is anything very wrong with that.

The 32-footer my wife Theresa and I cruised on for 11 years was very similar-a big, heavy double-ender-and ours was made of wood. While our 1937 William Atkin Thistle design differed significantly from the Union 36 and the modern double-enders that Bob Perry would later unveil (the Tayana 37 and Valiant 40, among the better known), these boats can be broadly traced to a common ancestor: the North Sea rescue boats designed by the renowned Norwegian naval architect Colin Archer.

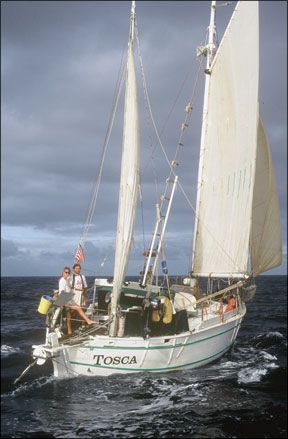

While Atkins Thistle is clearly a derivative of Archer’s work, Perry’s boats diverge so sharply from this archetype that they deserve a different branch on the family tree. The longer waterlines, flatter hull sections, and increased volume in the canoe-shaped stern of Perry’s boats reduced some of the more annoying characteristics we noticed in our boat, Tosca-among them a tendency to hobby horse and roll at anchor. Perry’s changes also made the boat faster and more weatherly.

Few cruising designs are so rich in maritime lore as the double-ender. Archers famous first rescue boat RS1 is a museum piece, as are the boats of famous solo circumnavigators Argentinian Vito Dumas (Lehg II) and Sir Robin Knox-Johnston (Suhaili). The wave of home-built post WW-II cruisers inspired by John G. Hannas Tahiti and Carol ketches, Atkins Ingrid, and L. Francis Herreshoff’s Marco Polo, further raised the double-enders legendary status.

When the age of fiberglass finally took hold in the 1970s, William Crealock’s Westsail 32, a thinly veiled copy of Atkins designs, rightly earned its place as the boat that launched 1,000 dreams.

While the double-ended concept holds many advantages, there are significant tradeoffs, and it is wrong to assume that just because a boat has a pointy stern, it is inherently a safer cruising boat. When it comes to seaworthiness, quality of construction and maintenance record can be just as important as design lineage.

Among the greatest disadvantages of many of these boats is light-air performance and weatherliness. During Tosca’s short hops in the Caribbean, these handicaps were striking, but once we set out west across the Pacific, we had no real complaints about the broader tacking angles and relatively sedate passages (average 112 miles per day). True, today we would opt for some more efficient and weatherly hull, but we still hold to the philosophy behind Colin Archers early designs: “Safety comes first.”