If we made a short list of traditional-looking cruising boats with trailboards and oodles of teak that dreamy-eyed readers most want to know about, the Cabo Rico 38 would be near the top. Others of her ilk, like the Canadian-built Gozzard 37 and 44, also draw much interest. But all that good detail in wood doesn’t come cheap. If you want to keep your investment at or below the six-figure line, you have to set the wayback machine on . . . well, wayback.

Still going strong after more than 45 years, the Bill Crealock-designed Cabo Rico 38 is much admired for its strength, seakeeping ability, and teak joinery work. While the original beauty was out of reach of the average cruiser, these days there are still some attractively priced boats popping up now and then. With the molds for this popular boat in limbo, it could well be that the only Cabo 38s we’ll see in the future are those that are out sailing today, and this shouldn’t hurt their value.

History

Cabo Rico has a rather unusual genesis, starting as it did as the hobby of John Schofield, manager of a British automotive plant in San Jose, Costa Rica, during the 1960s. A keen yachtsman, Schofield apparently saw no reason why his relegation to Latin America should quash his love of sailboats, so he began building boats in the corner of Leyland’s Range Rover facility. His first boats came out the door in 1965. By 1971, he had introduced the Tiburon 36 ketch, designed by Californian Bill Crealock. Six years later, in 1977, came the Cabo Rico 38.

Photos by Fraser Smith

Edi and Fraser Smith bought the company in 1987 and expanded operations. The Cabo Rico line includes models from 34 to 56 feet, most of which come with a pilothouse option.

In 1992, the Smiths bought David Walters Custom Yachts. If you know your fiberglass boat history, you’ll recall that David Walters is the yacht broker who, in 1975, co-founded Shannon Yachts with Walter Schulz. The Cambrias, envisioned by Walters as elegant competitors to Nautor Swan, Baltic, etc., include the 40, 44/46, 48, and 52.

Sent skidding by the recession of 2008, as far as we know, there are no boats currently in production. The last new boat we saw was a Chuck Paine-designed Pilot 42, at the 2007 Miami Boat Show.

The Cabo Rico 38, however, was for years the backbone of the company. Its 24-year production run rivals long-lived hall of famers like the Hinckley Bermuda 40. Naturally, the materials and methods used to build the 38 have evolved over the years. All told, about 195 of these hulls were built, not counting its predecessor, the Tiburon.

The Design

The Cabo Rico 38 is a traditional, full-keel design with a keel-hung rudder. The forefoot has been cut away somewhat to reduce wetted surface and improve handling. This is a trait of all Cabo Ricos, regardless of what designer-Paine did to the 40/42 and the 54/56; the rest are by Crealock.

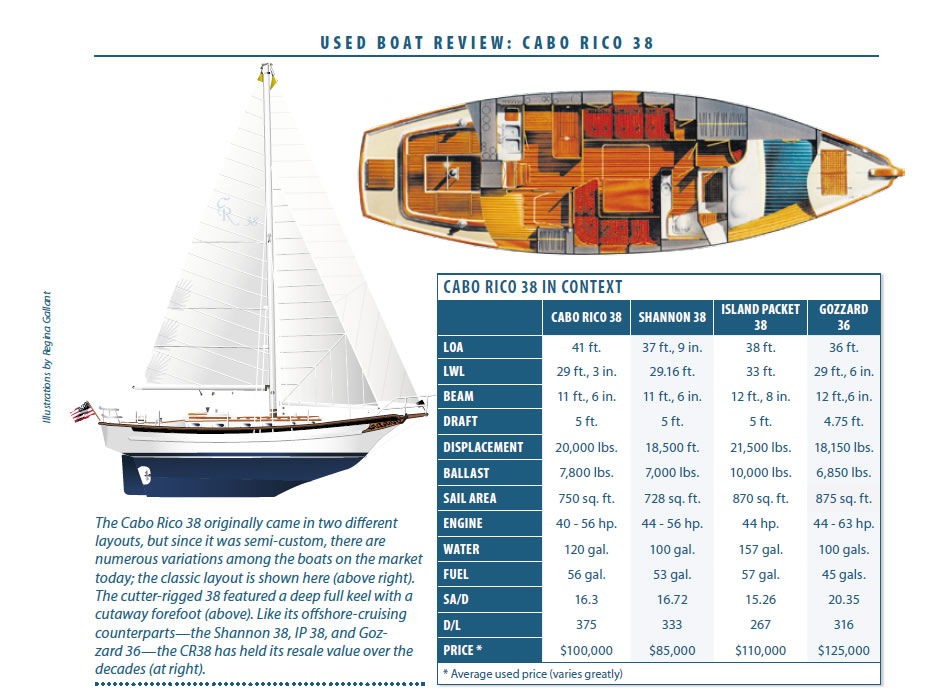

When evaluating any boat on paper, one of the first things you want to do is check the displacement/length ratio (D/L) and the sail area/displacement ratio (SA/D). These two numbers tell a lot about how the boat will perform, as well as its carrying capacity (generally, the higher the D/L number, the more volume inside the hull).

The Cabo Rico 38s D/L is 375, and its SA/D is 16.3. This makes the boat moderately heavy, with a medium-sized sailplan—about what you’d expect for a traditional, seakindly ocean cruiser. She has enough power to make decent passage speeds when the wind is up, but she won’t be a great light-air performer, especially when laden for cruising.

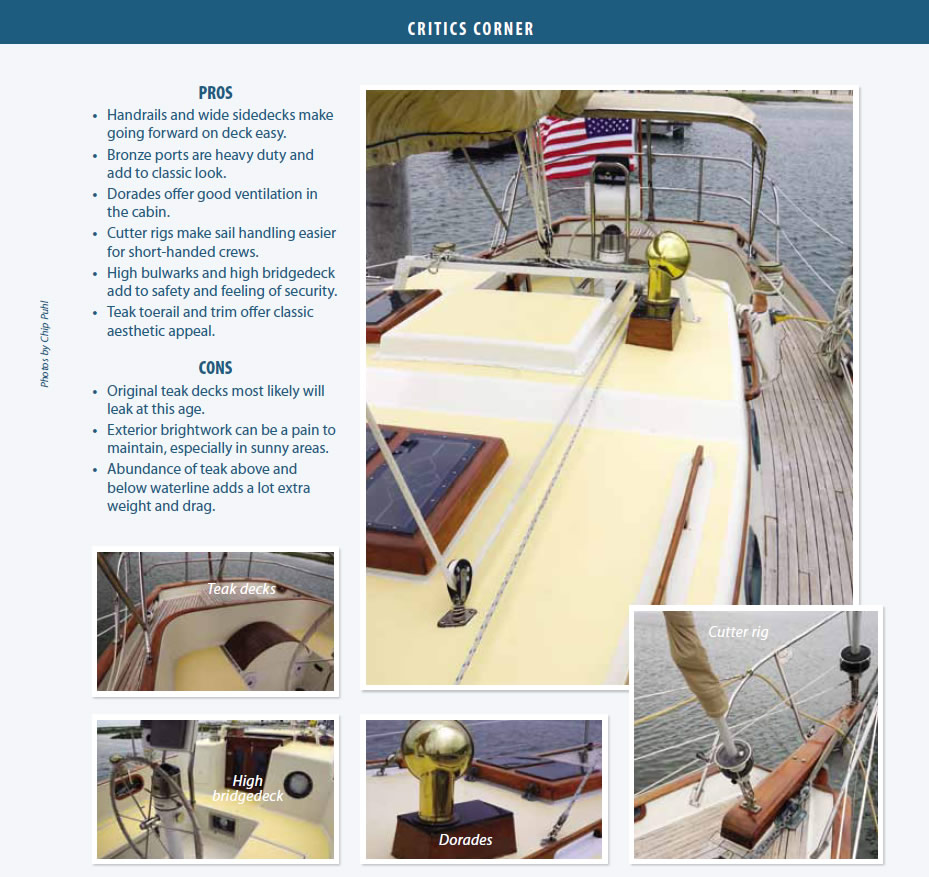

When viewed in profile, the clipper bow is prominent. This style is characterized by concavity, so that the bow seems to arch out over the water like a dolphin. The 38’s bow is adorned with real teak trailboards, not molded fiberglass (a hideous perversion seen on some boats).

There’s quite a bit of spring to the sheer line, with the low spot in the classic location, about two-thirds or so of the way aft. The conventional counter stern looks right. It has just a little overhang and is moderately broad. Many modern cruisers carry beam much farther aft than the Cabo Ricos; this increases cockpit space and stowage, but can present downwind handling problems that are avoided by the Cabo Rico’s conservative approach.

The cabin has a fairly low profile, with small opening portlights. The proportions are good; few design elements look worse than a cabin that’s too tall for the boat; that is, out of proportion to hull length and freeboard.

The rig is a cutter, which means the mast is located somewhat farther aft than on a sloop. It’s keel-stepped, so the designer had to plan where it would be in relation to the interior. On early models, the 38’s mast passes through the dinette table, which is perhaps unavoidable, but it does obstruct your view of your tablemates.

The 38—like all other Cabo Ricos, except the 34/36 and the 54/56—was also available with a pilothouse. However, according to Cabo Rico, although many clients liked the idea of an all-weather helm station, nearly all stuck with trunk-cabin models in the end.

Construction

The hull and deck of the 38 are fiberglass, and both are cored with end-grain balsa wood. (The larger Cabo Ricos are cored with Airex and/or Corecell.) Interestingly, the hull core is not centered between the two skins, but added inside to what is basically a solid fiberglass hull, then covered with a thin interior skin. The balsa is not needed structurally, according to the manufacturer, but it is added for insulation purposes. The company published its lamination schedule for the 38, which we think ought to be standard practice for all builders, but rarely is.

The deck coring is removed in areas where hardware will be attached, and deck hardware is installed by embedding stainless steel plates in the laminate, drilled and tapped so that hardware can be fastened by one person topsides. This method of hardware attachment is rugged and makes it easier for the builder, but metal buried in laminate inevitably invites corrosion. While it may eliminate washers, nuts, and backing plates, there is something to say about the simplicity and serviceability of traditional through-bolted deck hardware.

Early models were built with alternating layers of mat and woven roving, but there have been, as one would expect, many advances in the making of fiberglass fabrics since those early days. For later models, Cabo Rico primarily used 1708 and 1808 (8-ounce mat stitched to directional rovings) fabrics, along with vinylester resin for the first three layers (two of which are mat) inside the isophthalic gelcoat. This helps prevent osmotic blistering.

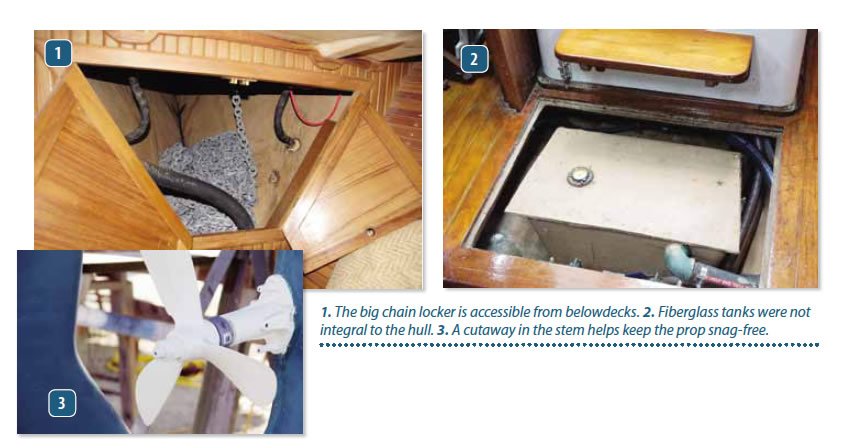

The keel is part of the hull mold, and in early boats, the ballast was iron. Cabo Rico switched to lead ballast for the last 60 or so models. There are seven separate castings, set in the keel cavity, and then the voids are filled with resin. The ballast is glassed over.

The hull is stiffened with U-channel fiberglass beams glassed to the hull. A fiberglass subfloor is placed over the beams, and then a solid teak and holly sole.

Portlights have no outside fasteners visible. The interior has no pan, but it is built up of plywood and solid teak or other hardwood. Since Cabo Rico 38s were semi-custom, you’ll find them with varying interior wood types-teak, mahogany, maple, ash, cherry.

Fiberglass moldings are used for the shower, engine beds, and icebox, which are good places to use fiberglass rather than wood.

When the 38 was born, teak decks were much desired. Cheoy Lee Shipyards of Hong Kong, one of the first offshore yacht builders to sell into the U.S. (and thereby an ancestral forebearer of Cabo Rico) sold a lot of boats stateside with teak decks.

Teak planks are generally screwed through the fiberglass deck skin and into a plywood core. The screws are countersunk, and the heads covered with bungs. Over the years, however, the deck and bungs expand and shrink, and begin to move. The glue holding the bungs ages and cracks. Eventually, water enters around the bung, seeps down along the screw, and into the plywood core. When the plywood begins to rot, the cure can cost you $25,000 or so. Also, teak decks add considerable weight to a boat, weight that is fairly high off the water.

While later Cabo Ricos could be ordered with teak decks, most owners opted for lower-maintenance fiberglass decks with molded nonskid rather than the warm beauty of the teak planking.

The hull/deck joint occurs at the bulwark and is bedded with 3M 5200 and through-bolted on 6-inch centers.

Tanks are fiberglass, but not integral, meaning they are molded separately and are not part of the hull. The bridge structure that supports the mast also incorporates the holding tank. Fuel capacity is 65 gallons; fresh water is 190 gallons.

The original engine was the excellent Perkins 4:108; that’s been replaced by the ubiquitous Yanmar-a 56-horsepower model. One owner completing our Boat Owner’s Questionnaire, however, said his 38 is equipped with a 70-horsepower Chrysler diesel built by Nissan. Other models had a Westerbeke 46, not enough horsepower, according to one owner and former marketing manager Allen Taylor (see adjacent article).

While most owners would seem to agree with the owner of a 1984 model who said his boat is designed and built for offshore cruising, the owner of a 1980 model complained that stanchion bolts are inaccessible, bulkheads aren’t all tabbed securely to the cabin sides and overhead, and all through-hulls aren’t bonded.

Another 1980 owner said that while his boat is overbuilt, its one flaw was a teak cockpit sole screwed into plywood, which completely rotted from water penetration.

Interior

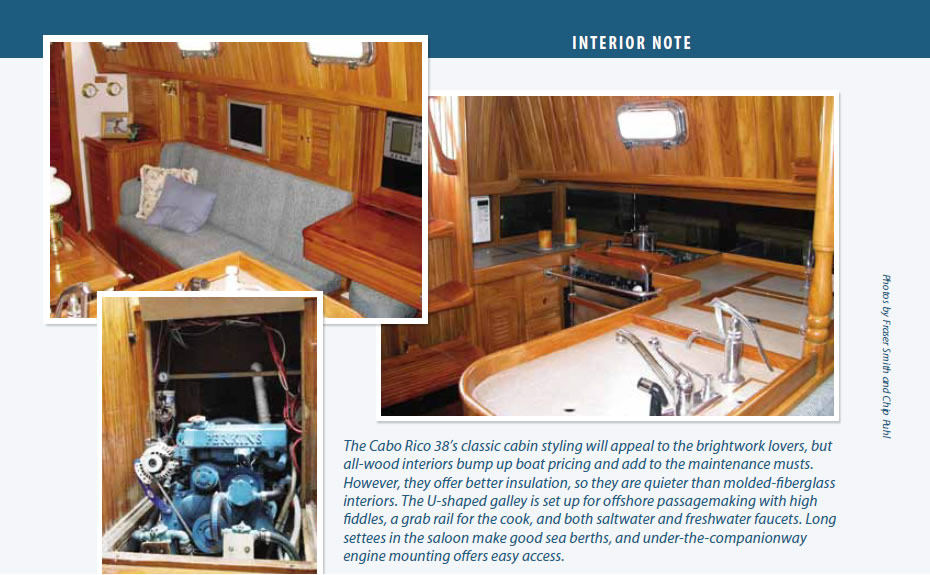

Early brochures show two basic accommodation plans for the 38. Plan A shows the usual V-berth forward, head, and hanging locker just aft of that, and amidships two settees with dinette table on centerline. The U-shaped galley is in the port quarter and to starboard of the companionway is a double berth.

Plan B is the same except for a rather unusual L-shaped dinette and a double berth forward offset to starboard. One leg of the dinette deadends at a bulkhead, making it appear that persons sitting there are more or less trapped by the table, which also runs to the bulkhead. Headroom is at least 6 feet, 2.5 inches, and berth lengths generally run 6 feet, 6 inches.

Later in the production run, the Offshore model emerged. This version eliminated the aft berth in favor of a massive storage area under the starboard cockpit seat. In this area, cruisers could fit large watermakers and gensets as well as find a place to store the gear required for voyaging. There was also a fold-up table and a larger, more functional nav station. Aft of the nav station, a large freezer area was added for additional food storage on long passages. Many other features were carried over from the earlier versions.

At the end of its production run, the CR38s interior was customizable, so you do see some custom layouts. One of the more common plans shows a V-berth forward, L-shaped galley to port (with access around both sides of the table), settee to starboard, U-shaped galley in the same port quarter area, and an aft stateroom in the starboard quarter area.

The aft double berth is larger than in earlier models, extending behind the companionway ladder. This is possible because the engine has been moved forward under the galley sink and dinette seat. Not only does this open up a lot of space under the cockpit, it makes engine access somewhat easier (by removing parts of the galley and seat), and also moves this heavy piece of machinery closer to the boats center of gravity. This should translate into less of a tendency to hobby-horse in choppy seas.

As mentioned, Cabo Rico does not use a fiberglass pan to form engine beds, berth flats, galley structure, etc. Instead, the interior is built up of plywood tabbed to the hull, which creates a sort of monocoque structure. Done properly, its very strong. There are many advantages to all-wood interiors, including better access to all parts of the hull (you can cut or smash your way into any compartment if you need to stop a leak caused by a collision below the waterline); and superior thermal and acoustic insulation (boats with wood interiors are quieter and dryer than boats with fiberglass pan interiors).

The problem is that all-wood interiors require many man-hours to assemble, which dramatically jacks up the price. Indeed, most boats with all-wood interiors nowadays are at least semi-custom yachts, priced well above most production boats.

Performance

During a test sail of the Cabo Rico 38, we found the boat to be well mannered, with few vices. With a bit of wind, it moves nicely. It was designed to strut its stuff in offshore conditions, not drift around the buoys. The moderately heavy displacement makes the 38 feel secure in the water; it doesn’t jump around like lighter-displacement boats. And the full keel gives it good directional stability; that is, it enables the boat to steer a straight line without a lot of attention to the helm.

The flip side of this, of course, is that full keels generally don’t allow boats to point as high as boats with fin keels. So, like everything else with yacht design, there are trade-offs. And while we are believers in the advantages of a full keel’s protection in collisions, directional stability, ability to careen boat for repairs, absence of worrisome keel bolts in most boats-we also appreciate the ability of fin-keel boats to point higher. At least in coastal sailing, pointing high can get you home faster, and faster is safer. Offshore, unless you’re clawing your way down the Antilles, it’s less relevant.

Owner estimations of their boats performance relative to other designs vary: While the owner of a 1979 model says of his, “Really not a racing boat,” the owner of a 1984 model boasts that he can consistently catch and pass boats that are faster by reputation. Most agree that speed is average-to-sluggish in light to moderate winds, improving to fast in higher wind strengths.

Of more interest perhaps than speed is sea-keeping ability, and here, the 38 excels. In our survey, owner after owner noted how well the 38 handles severe conditions: The rudder doesn’t stall, forcing uncontrolled round-ups; heel is easily reduced because of the cutter rig; and motion is more comfortable than on flatter-bottom boats. “Very solid and safe,” wrote one owner.

Conclusion

The Cabo Rico 38 is now a classic. At more than 40 years of age, the design still looks great, thanks to Crealock’s fine eye.

Our recent scan of the market showed early- to mid-80s Cabo Rico 38s being listed in the $70- to $80-thousand dollar range. A mid-90s boat is listed in the $170-thousand range.