For many of us, the falling of leaves marks the end of the sailing season. The boat is winterized for the season and our minds shift gears, away from sailing. As the new year comes, we catalog the winter projects we had intended to tackle. Bottom paint, of course. Fresh varnish may be needed inside and out. Deck fittings need re-bedding. Perhaps we have an ambitious fiberglass project, either repairing damage or adding something new. So much to do, so little time, and by March cabin fever has set in. Near freezing weather seems tolerable and a high anywhere near 50 F seems positively balmy. The problem is, while our circulatory system has acclimatized to bitter cold, the paint and adhesives used in all of these projects are cold blooded and require a certain amount of warmth to function.

Around the Chesapeake Bay, for example, many products can only be used without climate control between April and October. As a do-it-yourselfer, this can mean patiently waiting for warmer weather, missing out on some prime spring sailing.

The temptation to cheat is powerful. If you rely on professional services, did you push the yard to get the boat finished early, forcing them to work in cold weather? There is also the reality of boatyard economics; they need a certain amount of work for their men and a certain amount of steady billing through the off-season. Last winter , we watched the installation of a bow thruster proceed through February and March.

Epoxy was being applied at temperatures just barely above freezing, and temperatures plunged below 20F during the curing period. Was the strength of the fiberglass and the quality of the secondary bond compromised? Almost certainly. And the customer never knew. So whether you are doing the work yourself or contracting it done, mind the thermometer.

An infrared (IR) thermometer is a must for gauging surface temperature. Basically, it keeps you from cheating when you are anxious to get to work but shouldnt.

First Things First

Tend to anything that will get worse by spring. Change the oil now; theres no sense in letting acids sit there over the winter. Clean the water tank now and leave it dry. If there any leaks or failed bedding, fix it before ice does real damage.

Take the Work Home. If there is any possible way we can measure for the project, take pictures, and then prefabricate most of it at home, we will, even though it may add some complexity. Work will proceed at a relaxed pace, in a heated workroom, during the wasted hours after dinner. The temptation to take shortcuts is eliminated, since there is no pressure to get finished right now. We can apply multiple coats of resin, paint, or varnish, and to take our time with details.

- Cardboard mock-ups are a great adjunct to measurements.

- Design the project so that it only requires trimming and attachment to the boat.

- Package all the parts and fasteners in Ziploc bags. Saves time and confusion at the boat.

Tenting is sometimes an option, but strong winds can make this impractical and using heaters is risky.

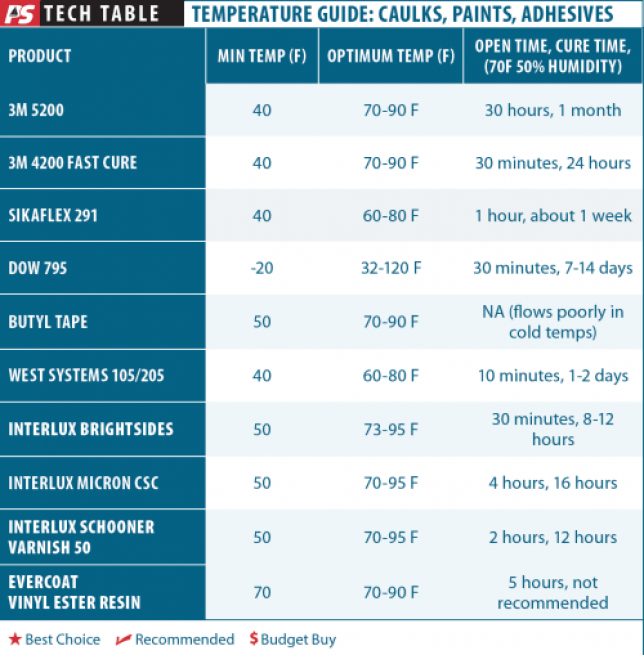

Chose Your Products. Temperature range is one consideration, and volatiles are another. Although we like polyester resin just fine for many projects, we avoid it in the winter for two reasons. First, polyester requires warmer temperatures than epoxy. Second, the resin is dissolved in volatile and highly odiferous styrene, making it dangerous to work with in confined spaces. Workers have died applying polyester resin inside large tanks, and how different is a closed up boat cabin from a tank, really? If the desired product doesn’t meet temperature or safety requirements, change the work space, product, or wait for warmer weather.

Heating. The first consideration is safety. Most yards prohibit operating heaters unattended, for good reason. They can tip, combustible materials can fall into them, and many projects involve flammable solvents.

Ventilation. The problem with heating the confined space of a boat cabin, even more than a house and far more than a garage, is that it is small and sealed. Air exchange is necessarily limited to retain warmth, and thus what-

ever chemicals evaporate into the air stay there. Dangers of both flammability and toxicity compound. Health effects aside, many solvents can reach explosive levels after just a few ounces evaporate in a small space. Respiratory protection is even more important. Always have extra cartridges handy, and don’t expect them to last all day.

Other Spray Options

Minimize solvent use. Dried up adhesives can often be removed with a scraper or wire brush; a cup brush on an angle grinder is very fast for large areas, and a smaller brush on a cordless drill is versatile in tight spots. If the adhesive has not become friable, try softening with a heat gun and then scraping.

CO monitor. If you are using a fired portable heater, bring a monitor from home if you must. The space is much smaller and solvents passing through a red-hot space heater are often imperfectly combusted. Never use paint strippers or products containing methylene chloride or any other chlorinated solvent when using a space heater; incomplete combustion of the vapors as they pass through the heater will generate phosgene and other highly toxic gases. The EPA is considering banning the sale of methylene chloride for safety reasons.

Heat the substrate, not the air. The instant you put the paint or glue on the boat it reaches the temperature of the boat.

Warming both sides. Often the fan can be used to force warm air between the hull in the hull liner, or in the locker spaces. Insulation placed against the hull (large fiberglass batts are very effective) can promote warming of the hull without cumbersome tenting.

Get it hot inside. Particularly effective solution, when possible, is to heat the interior to T-shirt temperature. This will warm all of the cabinetry, the liner, and even parts of the hull to acceptable temperatures. More importantly, if the product has a relatively short curing time (fast cure epoxy systems and some paints) the surfaces will remain warm for many hours after you leave, even with the heat turned off.

Paint and varnish. Viscosity increases and they don’t flow out like they did in the summer. Bubbles may not pop and coatings can be too thick. Warming the can to 70-80F helps it flow off the brush, but it cools to surface temperature on contact. Adding extra solvent to improve flow will compromise finish hardness. Slow drying can allow moisture to enter the finish, causing fogging in varnish and gloss reduction or blotchiness in paints. However, we don’t recommend accelerators; they seem to reduce the life of the finish by reducing flexibility (it cracks).

Bottom Paint. Solvent-based paints are often applied successfully by boatyards slightly below the minimum recommended temperatures, with daytime highs in the 40s and cold nights. However, failures of water-based paints have been documented when were applied below recommended temperatures. The curing mechanism of aqueous paints is very different than solvent-based paints; without some warmth during the drying and curing period the binder does not coalesce properly, the film is weakened, and the bond may fail.

Two-part adhesives and paints. Do NOT adjust the hardener/resin ratio in the hopes of attaining a quicker cure or adjusting the temperature limit. Yes, the product will cure more quickly, but the resulting strength can be as much as 10 times less. Its in the manuals and weve made the mistake. Epoxy should always be measured using calibrated pumps or scale, and do not deviate from the stated ratios.

Do not heat the resin and hardener before mixing. They should be warmed to room temperature (60-70F) to promote good mixing, but heating above that will shorten the pot life to just a few minutes, without measurably reducing the cure time; remember, as soon as the epoxy is applied it will cool to the temperature of the surface.

Sealants and Adhesives. Polyurethane products like 3M 5200 and Sika-

flex 291 rely on moisture to cure in the same way that epoxy relies on resin plus hardener. Not only is the curing process slowed by low temperatures, it is also slowed by low humidity. Because cold air holds far less moisture, 40-50F air, even warmed to 70 or 80F, contains too little moisture to cure polyurethane adhesives. 3M 5200, which is slow to cure under warm and humid conditions, can take months to cure in either cold weather or in a very dry heated space, such as a heated garage. We frequently hear from do-it-yourselfers confused when a sealant refuses to cure even when they put a heater on it for a week. The problem isn’t temperature, it is low humidity. The solution is to boost the humidity.

- Small projects can be placed in a large cooler with a bowl of water and a heating pad.

- Larger projects can be misted with water and then covered with a tarp.

- Warm sealants to 70F before using; at low temperatures they thicken, are very difficult to pump, and will not flow properly into the gap.

Were not fans of silicon sealants, other than for glazing, largely because of the residue they leave behind. However, they are the only sealants that can be applied when its really cold (down to -20F). The surface must be free of frost. Curing is slower, but even in extreme cold, overnight is generally enough.

Working with plastics. Coatings and adhesives arent the only materials that suffer in the cold. Weve already warned you not to flex soft vinyl windows below about 50F because they can crack.

Hoses get stiff and will fight every inch of the way when fishing them through tight spaces. Getting the hose to expand enough to fit over a hose barb can be a real battle. Warm air helps, but use moderation with a heat gun or even a hairdryer; its possible to damage the hose through localized overheating.

Very hot water is a very effective way to soften the ends of notoriously stiff sanitation hoses, just be very careful not to tip the pot and scald yourself. Even wire becomes stiff because of the insulation.

And then there are practicalities.

Shorter days make it hard to get much done. At noon the sun will be at afternoon levels, and afternoon like dusk. Fall is bad, but spring is better (mid-November is one month from the shortest day, but mid-March is the equinox, half-way to summer). Although your project may seem well lit, it isn’t, and painting and varnishing in poor light is asking for mistakes. Bring portable lights.

Overdress. If you must work with bare hands, overdress. My college landlord-a veteran Antarctic researcher-taught me that your hands can be great radiators of heat if the rest of your body is sufficiently dressed. If you must work barehanded in a cold setting, particularly if you will be sitting still for a time, pull on a hat and insulated coveralls. You want your body to be on the verge of overheating, forcing the extra heat out through your hands.

Conclusions

Its tempting to jump-start your spring, but varnish and Sikaflex don’t acclimate the way you do. Reading product tech sheets is a big step toward avoiding disappointing results.

We can’t imagine missing the first warm days of spring except for the most necessary projects. Any cosmetic work can usually be squeezed into a windless summer day.