Alphabetical Boat Reviews?

What happened to your alphabetized boat reviews. I’m looking for a boat and can’t find the review I was looking at before. I regularly crew on a J130 in Charleston Harbor and recently sold the second Hobie 16 I’ve owned. I need something larger now that I’ve got 11 grandkids (and counting) with eight of them living in the same general vicinity.

Steve Mattie

Boat TBA

Charleston, SC

The alphabetized boat reviews should be back up in short order. This glitch was among many that occurred as we upgraded to the new website. We a very sorry for any inconvenience.

one of many subscribers who urged a return to alphabetized

online boat tests—now in the works.

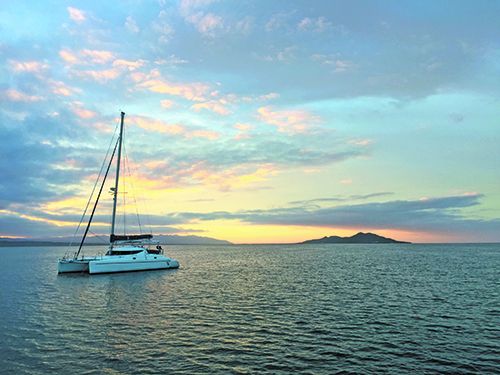

AIS Antenna Placement

Regarding your recent report on AIS antennas (see “Special Report: How to Prevent AIS and VHF Antenna Malfunction,” Practical Sailor February 2019), we pulled the mast on our cat in early 2016 for a re-rig, and re-cabled all electronics in new conduit at that time. Also installed a second VHF antenna for AIS only, not knowing that this was not recommended. Curiously, we have seemingly well-functioning VHF and AIS, although other boats have noted that we disappear periodically off their AIS screens, as they do from ours. I’ve associated these episodes with VHF use, but not entirely sure. I feel like the two antennas will only really interfere when both transmitting at the same time, which only happens intermittently, and for very short duration. Would having a VHF in use—on either end—disrupt the pings of the AIS system, causing it to disappear?

Randy Fraser

Free Luff, Pajot Athena 38

Kings Beach, CA

Without further testing of your system it would be hard for us to determine the impacts of your antenna arrangement. However, experts agree that having two closely placed VHF antennas is undesirable. In short, you should look into modifying your setup. Renowned offshore navigator Stan Honey, and Volvo Round the World Race technician Dan Jowett addressed this topic (see “Special Report: How to Prevent AIS and VHF Antenna Malfunction,” Practical Sailor January 2019). We’ll quote the relevant section here, with italics to emphasize the advice against having two operating VHF antennas closely placed together.

“Offshore Safety Regulations (OSR) for the offshore racing require that the VHF whip be mounted at the masthead. This makes sense because daytime VHF range, when there is unlikely to be ducting, is limited to line of sight. For you to have a reasonable range (e.g. 7 to 8 miles) to receive a call for help from somebody using a handheld VHF at deck level, sailboats should take advantage of the height of their mast.

OSRs permit the AIS to either share the primary antenna via an AIS antenna splitter, or to use a dedicated antenna that is mounted at least 3 meters above the waterline. Given that one of the most important uses of AIS is to locate a person in the water wearing an AIS MOB beacon, the masthead location is important if you want to receive AIS MOB beacon signal from the maximum possible range (about 1-3 miles depending on mast height). Thus, it makes sense to use an AIS antenna splitter and share the masthead VHF antenna for both VHF and AIS. The AIS will not receive while the VHF is transmitting on voice, but AIS MOB beacons repeat their transmissions frequently, and MOBs don’t move very fast, so the shared antenna at the masthead makes the most sense.

VHF antennas should never be mounted closer than one wavelength, which in the case of marine VHF is nearly 2 meters. Thus it isn’t possible to mount two VHF antennas on the same masthead.”

In your case, the simplest solution will be to invest in a high quality splitter. We’ve tested the Vesper Marine splitter with good result (see “Chandlery-December 2013,” Practical Sailor, December 2013).

As the Northern Hemisphere shakes off winter and spring-cleaning gets under way, many sailors are busy with do-it-yourself projects, the usual marine maintenance fun, and prepping for summer sailing. Here are some archive articles to help you tick off the tasks on your to-do list.

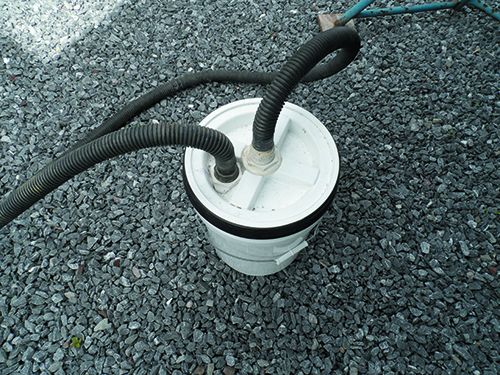

DO-IT-YOURSELF

For the DIYer, we have a slew of possible spring projects worthy of your time. Cruisers will want to look into the trysail-track refit report (May 2012) and the blog post on how to build your own custom medical kit (Inside Practical Sailor, June 12, 2014; July 2014 PS issue). Keep the boat cooler this summer by installing some DIY fiberglass hatch covers (March 2016). For the maintenance-minded, there’s a comprehensive look at gelcoat restoration in the June 30, 2014 Inside Practical Sailor blog, as well as articles on DIY blister repair (February 2011) and re-doing your teak decks (June 2011). If your spring chores include sanding off bottom paint or teak, check out the how-to for a DIY dustless sanding bucket in the April 2016 issue.

MAINTENANCE

Wondering what the best products are for those spring-summer cleaning jobs? Be sure to read our test reports on boat soaps (January 2013), waterline stain removers (April 2014 and November 2007), isinglass/clear-vinyl cleaners and protectors (May 2014 and March 2009), and hull waxes and polishes (Inside Practical Sailor blog April 9, 2014 and July 2014 PS issue).

Warm-weather safety

The editor’s blog “Sun Protection and Sunscreen for Sailors” (May 13, 2014) contains links to a library of reports on UV-protective shirts, hats, and sunscreens that we’ve tested. Are those Oakley’s really worth $200? Our June 2017 article “Boating Eyeware Guarantee” finds out. One of the most often overlooked safety precautions for sailors in warm climates is staying hydrated on the water. In the June 2010 issue, we took a look at why hydrating is important and the best ways to stay hydrated at sea.

Safety

Our archives are overflowing with safety-gear tests and tips articles. Check out our safety tethers (September 2011) and PFD-harness tests (July 2013 and August 2008), and the feature on life-raft inspections (February 2013). In 2012, we reported on three racing accidents, each with important lessons for all sailors: WingNuts capsize (April 2012), Rambler 100 capsize (May 2012), and the Low Speed Chase (Farallones) capsize (June 2012). And in “Practical Tips for Survival at Sea” (June 2013), author Michael Tougias offers advice from survivors on what they would have done differently and what helped them survive. For a compilation of decades of PS safety tests and advice articles, check out the “MOB Prevention and Recovery” ebook, which is available at https://www.practical-sailor.com/products.

Ionizer update

I’m a recent subscriber and your magazine offers generally great info so thank you. I read the letter concerning mold from Peter Berman (“Ionization Versus Mold” Mailport, PS February 2020) this morning and then promptly looked into the issue a bit more. Based on some online reports I found, the letter seems to suggest an incorrect, or at least, a very incomplete solution. I think you owe it to your subscribers to vet a piece of advice that is stated as fact before you publish it.

Matthew Clark

Via PS Online

Baja, California

There is a difference between a common ionizer and an electrostatic ionizer precipitator, also called electrostatic ionizer. In an electrostatic precipitator, the ionized air is not just blown out in the atmosphere. It is instead passed through collector plates, which have the opposite charge, and the fine solids are collected there, where they are then periodically removed by neutralizing the charge and shaking the plates clean. The ions don’t “clean” the air, they just make the particles momentarily sticky. Their effectiveness for reducing indoor air pollution has been debunked, but they may help reduce the spread of mold spores.

A similar device that has been strongly debunked is an ozone generator, an odor-fighting product that we once advocated for, until later studies proved it ineffective and possibly dangerous. Ozone is a powerful oxidizing agent, more powerful than hypochlorite (bleach). Not only is it damaging to fabrics, sealants, and rubber in the same way that UV and bleach are, it can be harmful to health in enclosed spaces.

Does it kill mold? Possibly. Like chlorine, ozone is sometimes used to disinfect water. However, like bleach it has very poor penetrating properties and will only kill microbes on the very surface and not those in the upholstery or the roots in wood. EPA studies report that the minimum ozone levels required to prevent even airborne organisms from regenerating exceed safe health standards by 5-10 times.

Can an ozone generator remove odors? Possibly. It does so by chemically burning them up, just as bleach is used to remove certain tastes and odors from drinking water. However, these reactions can be very slow in many cases and the required levels many times higher than health standards. Practical Sailor continues to recommend less expensive means of controlling mold using dehumidifiers in the off season, and ventilation during the sailing season, supplemented by cleaning and treating areas with one of our recommended mold preventatives—some which cost less than a penny per ounce.

See the Inside Practical Sailor blog post “Homemade Mildew Preventers that Really Work,” for more details, including links to our report on dehumidifiers, and our special report on Marine Cleaners (www.practical-sailor.com/products).

Steering Systems

I’d like to add my “two bits worth” concerning steering systems. I have a 1997 J-42 with Whitlock’s Cobra rack and pinion steering system and I can’t imagine a better steering system.

The wheel travels about 340 degrees lock to lock which means it almost like steering with a tiller. The feedback is terrific because there’s essentially a solid link between the wheel and the rudder. The cable systems I’ve experienced just don’t compare. I’ve probably got a about 7,500 miles under the keel and the system still works like new. I’d like to hear from others about this system and whether your cons and comments about wear and friction have actually been experienced.

Bill Boyeson

Jiminy, J-42

Seattle, WA

St. Augustine, Florida. Jackson’s previous boat was 27-foot Pacific Seacraft Orion.

Fathead Sails

Further to the article on fathead sails (see “Pros and Cons of a Fathead Sail,” PS February 2020), my neighbor and I have converted our formerly wishbone rig Nonsuch 26s to fatheads. Last year was our first full season with the new rig. Performance in the sailing trials exceeded our expectations. Our sail plan incorporates the ultimate fathead using standing gaff, which eliminates the need for 45-degree top battens. We had three objectives prompting the conversion:

1) Improved safety. A 15-foot boom that does not intrude into the cockpit or hang over it supported by a topping lift that might fail. The mainsheet attaches ahead of the dodger and feeds to the cockpit through the dodger. The boom, now mounted four-feet above the deck providing excellent lines of sight in all directions.

2) Improved seaworthiness running and reaching in heavy weather. Jibing using two spars with less weight than a wishbone reduces forces at play considerably.

3) Improved balance with reduced weather helm causing less strain and wear on steering components, rudder bearings and the helmsman.

With our Nonsuches, we have the advantage of no stays. We do have sheets to trim the gaffs which have proved to be effective and help share the load on the mast. The sail area is 5 to 10 percent less than the standard Nonsuch, but the change has reduced drag from excessive weather helm. Another advantage is reduced need to reef as the boats’ remain in full control from near 0 to over 30 knots. The original wishbone rig sails at its best with a single reef over 15 knots and a double reef over 25 knots.

In our first season, we were competitive with standard 26s except going to windward where they had an advantage. Modifications we make this year should improve performance to windward. In reality, the Nonsuch sail is a genoa. To achieve the desired shape we will be using much softer battens and a few other tweaks. If I had to do it again, I would use rings/hoops around the mast to align the sail better with the mast and create an improved airfoil.

Safety should be the primary concern of a cruising boat. One may be far from hospitals and medical assistance, unlike the kids racing around the cans near urban centers. We have found the new rig more enjoyable to sail with less heel and better able to tack smartly in one to two-meter seas.

We chose the standing gaff so we did not have to raise and lower it or having it swinging about when dropping or raising sail. It is a practical solution for a Nonsuch 26. In addition, it can be deployed as a crane for launching or shipping a tender. It might come in very handy in a MOB situation. I hope we never have that situation, but need to be prepared for it!

John Newell

Mascouche, NS 26 #1

Toronto, Canada

mainsail to squeeze some extra fun out

of his Nonsuch 26 Mascouche.

Don’t Clean Tank with BAC

I have an IP 320 with aluminum tanks, preventing me from using chlorine-based treatments. My IP boat broker friend suggested Multicide, a disinfectant used in restaurants. The active ingredients are alkyl (50 percent C 14, 40 percent C12, 10 percent C16) and Dimethyl Benzyl Ammonium Chloride. The other ingredients, 90 percent, are not listed. Do you know anything about this? I’ve subscribed for years to your awesome magazine but never heard of this. My memory isn’t great, but I can’t remember any advice from you about treatments for aluminum tanks.

David Jackson

Trixie, Island Packet 320

St. Augustine, FL

Multicide is a quaternary amine, commonly used in antibacterial hand soaps, for example. Although relatively safe as surface disinfectant, it should not be used on a potable water tank. If you have sterilized a tank with these, they should be completely flushed from the system. Our recommendation for aluminum tanks remains dichlorisocyanurinate, most widely available as Aquamega tabs or Puriclean Tabs. It is may times less corrosive to aluminum than chlorine and is certainly harmless for annual sanitizing. If the water source is U.S. tap water, annual sanitizing of the tanks should be all that is needed. The tabs were tested in “Keeping Water Clean and Fresh,” PS July 2015. We’ve been using them for several years in our own tanks. For complete guidance on clean and safe water while cruising, see our brand new three-volume ebook series on “Onboard Water Treatment, Storage and Production” at www.practical-sailor.com/product.

Practical Sailor welcomes reader comments and questions. Send email &

reader photography (digital .jpeg 1MB or greater) to practicalsailor@belvoir.

com; include your name, homeport, boat type, and boat name. Send any broken gear samples to Practical Sailor, 1600 Bayshore Rd., Nokomis, FL 34275

Winter almost being over, it’s probably too late to pass on some tips we learned living aboard out Catalina 350 in Chesapeake Bay. But, I will anyways. Probably the most cost effective thing we did was use shrink wrap storm windows on all the deadports in the cabin trunk and the lights in the swinging companionway doors. Reliably kept condensation of the ports even when the outside temps dropped into the low 20’s and still let light in. We also insulated the cabin top ports and below the rubrail ports with one inch hard, Styrofoam insulation cut to fit. A check with a laser thermometer showed the ports were warmer than the cabin roof (measured from the inside). Our other “win” was cutting to fit several cheap anti-fatigue mats for the cabin sole. Raised the temperature of the floor by five degrees and made sitting at the cabin table so much more pleasurable. Still working to find better ways to control condensation…sigh…never ending battle.

In the Caribbean it is common practice to wax a boat before lay up for hurricane season, then again after returning to the boat, often in November or December. Having read several times in PS that wax provides little UV protection, and given that our boats are not seen for six months while on the hard, is there any real return on the considerable expense and/or elbow grease before storage? Would not waxing just before winter launch be just as effective in preserving the gelcoat and fiberglass?

Thomas Nunn