Tony Smith sure knows how to make the most of a good thing. The British multihull lover has gotten more mileage out of one design than any boatbuilder we know. And why not? With more than 200 Geminis built to date, and interest building, why switch?

History

In 1972 Smith designed and developed the 26-foot folding trimaran Telstar in England. He brought the molds to the U.S. and built 350 of them before a devestating fire destroyed the molds in 1981. Desperate to resurrect his business, he grabbed some old catamaran molds he had—the Aristocat—changed the name and that same year launched the first Gemini 31.

Three years and 27 boats later, he retooled to produce the Gemini 3000, which is essentially the same boat, but longer. Today, yet another incarnation of that first design—the Gemini 3200—continues to sell well.

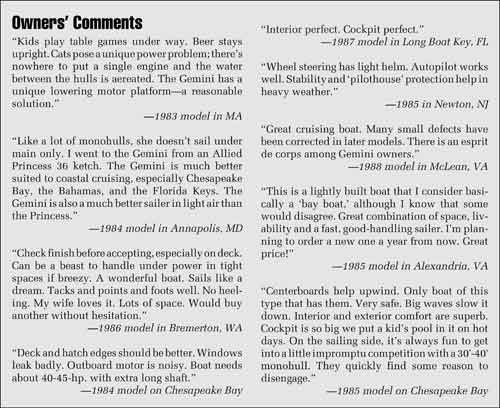

Several years ago, Smith planned to introduce a larger 37-foot version, but the cost was much higher and despite building one boat, he changed his mind. The multihull business in this country has been slow to take off. And as even the established monohull builders like Pearson and C & C have found out, there ain’t much room for error. Instead, Smith has refined the Gemini much like the Volkswagen Beetle. By listening to owners’ comments, and by incorporating his own evolving ideas, the boat has changed a good deal, though one would be hard pressed to distinguish, at a glance, between a 1984 Gemini and a 1992 model.

Design

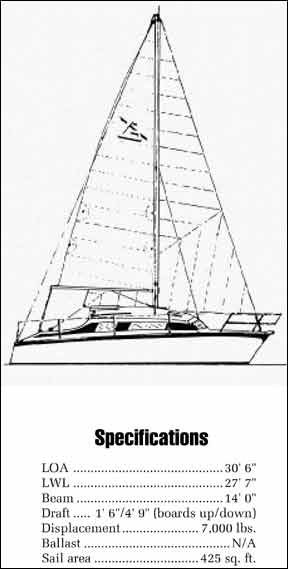

The funny thing about the Gemini is that it’s an old design. Ken Shaw drew the lines in 1969. There’s nothing particularly contemporary about it. However, by painting the cabin sides black (Euro styling), adding a swept-back fiberglass “pilothouse” and gradually adding length to the full-bodied hulls, the Gemini has always looked like she belonged with her contemporaries, whether that was the 1980s or 1990s.

The most important thing to remember when evaluating this design is that the Gemini is essentially used as a 30-foot live-aboard, cruising catamaran. While faster than most monohulls of equal length, it has no pretense of being a racer. How could it be with such a spacious interior? Further, many of Smith’s customers are older folks who are tired of heeling, don’t have $200,000 to spend, and don’t plan to circumnavigate. In fact, most Geminis we’ve seen are happily puttering up and down the Intracoastal Waterway along the Eastern Seaboard and Gulf Coast. It’s perfect for that.

Summing up the design gets a little dicey when offshore work is discussed. The Gemini’s liabilities here are several. Because of the substantial accommodations built on the bridge, which necessitates lowering it for headroom, and the solid bridge forward (as opposed to netting), it’s a bit heavy. Smith says that if loaded for extended cruising, there is not a lot of clearance between the bottom of the bridge and the surface of the water, and it will pound going to weather in choppy seas. Sailed light, the Gemini will do quite nicely and be much more comfortable.

The performance of full bridgedeck cats, such as the Gemini, also suffer a bit from the extra weight and windage. Smith, a racer at heart, admits that if he had his druthers he’d build an open bridge forward, but for his cruising clientele, the full bridge makes more sense.

Nevertheless, Geminis have, according to Smith, crossed the Atlantic, cruised the South Pacific and Caribbean.

Having spent a week cruising the Chesapeake Bay aboard a Gemini 31, we found the boat extremely comfortable and fun to sail. With a large queen-size stateroom forward and double staterooms aft in each hull, there’s room for Mom and Dad, Junior and Sis, each in their own private cabins.

Speed reaching and sailing upwind was about 50 percent faster than what we could do in our 33-foot Pearson Vanguard. We hit double digits just once. But sailing in moderate winds we’d make eight and nine knots when our Pearson would do five and six. Three or four knots may not seem like a lot, but for sailboats on an all-day passage, the difference cuts hours off sailing time.

Best of all, it’s level sailing. This makes for very restful cruising.

Punching to windward in a chop, we did buck a bit, and the quicker motion of a multi takes some getting used to. All in all, we came away impressed with its space and performance.

Construction

The key to high-performance multihull construction is lightness and strength. The rapid evolution of composite building techniques now makes possible the use of lightweight core materials, specialized fibers such as Kevlar, and strong resins that in combination yield a panel that is much lighter and stiffer than solid fiberglass or fiberglass with just “traditional” core materials such as end-grain balsa and PVC foam. Vacuum bagging helps assure uniform bonding of all the “parts.” Naturally, such construction is costly.

Construction of the Gemini, which is marketed as a comfortable, low-priced cruising catamaran rather than a spartan high-tech racing machine, is quite conventional. The hull is built of solid fiberglass—mat and woven roving. The deck is cored with balsa for stiffness. The new Gemini 3200 incorporates a layer of vinylester resin as a blister barrier. Twenty percent of the owners of older models responding to our survey reported “some” blistering—a below average incidence.

The centerboard trunks were laid up separately in the early boats, but Smith said it was difficult getting good tolerances for the centerboards to fit right. Now the trunks are part of the hull mold and the slot is a guaranteed two inches and the polyurethane-coated plywood centerboards 1-7/8″.

Obviously, to keep weight light, a multihull builder isn’t going to use any unnecessary laminations. Consequently, many multihulls feel flimsy compared to monohulls. One Gemini owner said, “The strength is a little lower than I would have liked, but it helps hold the cost down.” And, we might, add, the weight that is so important to multihull performance. The rock steady feel of thick decks is somewhat at odds with the requirements of multihull design and construction.

A frequent complaint of Gemini owners is gelcoat flaws. “Gelcoat has many voids,” wrote one owner. “Some gelcoat yellowing and crazing,” said another. The interior woodwork is acceptable to some owners, and not to others. “Woodwork finish is inept,” said one owner. “Finish work is my biggest complaint,” said the owner of a 1985 model.

Smith admits that leaky windows were a problem in early boats. The design has since been changed, including the use of Lexan in place of Plexiglas, and a new system to bed the large panels allows for thicker beads of sealant to absorb the expansion and contraction of the windows.

Most owners, however, seemed to feel that these are minor problems they’re willing to live with. They rate construction lower than other attributes of the boat, but overall still are satisfied with their choice of the Gemini. We’d like to see a bit more glass in the Gemini, or the use of a core for stiffness and strength, though we acknowledge it would increase the price.

Performance

Besides accomodation space and low heel angles, speed is a major factor in choosing a multihull. Only one owner expressed disappointment in his Gemini’s maximum speed attainable. True, it won’t hit those 15- to 20-knot speeds possible in more performance-oriented cats and tris. Nearly all owners, however, remarked on the Gemini’s good light-air performance. And, as we found during our week’s cruise of the Chesapeake Bay, the boat is definitely faster than a cruising monohull of equivalent size.

A key to performance in any multihull is keeping weight down. Unfortunately, many owners overload their boats and this has a direct effect on speed and pointing ability. It’s a problem with no easy answers for live-aboards and long-term cruisers: Either buy a boat with longer hulls and hence greater payload capacity, or live with sub-par performance.

A significant feature of the Gemini is its centerboards, which improve pointing and tacking considerably. Many production catamarans today have fin keels on each hull. The thought here is that the problems inherent with centerboards (broken pennants, jammed boards in the trunk) are eliminated, while acceptable upwind sailing characteristics are retained. This may be true, but there seems no denying that centerboards improve overall performance. Further, the fins add to wetted surface, which increases drag and adversely affect maneuverability.

It is interesting that author Bernard Perret wrote in the October 1990 issue of Cruising World regarding his search for a cruising cat: “We focused in on exactly what we wanted: two sideboards to help us tack more efficiently against the wind and to maintain a shallow draft…”

Having ourselves sailed on production cats without centerboards that were dogs to windward (close reaching was virtually impossible, leaving motorsailing the only option), we consider daggerboards or centerboards an important criteria in selecting a catamaran. Perret said he tacks his French-built 36-foot Naviplane through 115 degrees true, but that’s nothing to write home about. We’re sure he could do better if he wasn’t loaded down with cruising gear for five. Under optimal conditions, Smith says the Gemini can tack through 80 degrees. Burdened with bicycles, computers, three anchors, a library, and food for six months, that number is sure to increase.

A number of owners noted the boat’s lack of directional stability (because there’s not a lot of boat underwater). But they also acknowledged that it is very easy to steer, and that with the lee board down, it balances nicely.

The wide sheeting angle of the early boats made the genoa inefficient upwind. Smith says this has been improved, by means of lengthening the track, in the Gemini 3200.

Under power, the Gemini performs well. The outboard turns with the rudders for assistance in close quarters—most multihulls need it. And it retracts for sailing. The arrangement has been modified several times over the years.

The current Gemini 3200 comes equipped with a 40-hp. Tohatsu. Some 31 owners felt more power was needed. The results of our recent Reader Survey didn’t rate Tohatsus very highly, but Smith says a 25-inch shaft is very important for maximum performance.

The Mercury 35, standard on Gemini 31s and 3000s, is no longer made. The Tohatsu, he said, is the only engine in that power range available with a 25-inch shaft. In any case, motoring the Gemini at decent speeds, and in comfort, is certainly possible, though punching into head seas isn’t its cup of tea—multis are too light and their motors often too weak to grind out the miles like a heavy, diesel-powered monohull.

Twin Yanmar and Volvo diesels were available, but at such an increase in cost, few buyers would consider them. We’d take the outboard for cost savings, clean interiors, and ease of repair and maintenance. So what if it’s a little noisier? You’ll motor less with a catamaran than your old monohull anyway.

Accommodations

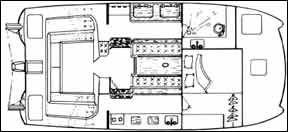

There are numerous appeals to the cruising cat—the large foredeck, large cockpit and the possibility of three or more private sleeping cabins. The Gemini has all three.

The full bridge means there is no netting between the hulls as seen on many cats. This adds weight, but does help deflect waves. From a particularly hedonistic point of view, the netting is best for lying on face down, watching the water fly by. On the other hand, footing is precarious. The full bridge makes anchor handling easier and provides for possibly a little extra stowage space.

The Gemini’s cockpit is large enough to walk around in, with good footing and stowage. Bulkhead wheel steering is convenient whether standing under the so-called pilothouse (added after hull #10), or sitting either on the bench seat or coaming top.

There is not standing headroom in the saloon forward of the 6′ 2″ pilothouse, but this isn’t a major item. Several interior plans have been offered over the years. The one we chartered had a 64″ x 75″ double berth forward in the starboard sector. The view from the bunk looking through the forward windows is stunning! The head with shower was in the port bow and aft, in each hull, was a quarter cabin. The 48″ x 75″ bunks in these weren’t quite as wide as a couple might like, but tolerable, and certainly more than big enough for kids. The nav station was amidships to port and the galley in the starboard hull, with 6′ 3″ headroom. Headroom forward is 6′ 0″ .

An interesting dilemma of outboard-powered boats is the question of generating power for live-aboard conveniences. Outboard engines aren’t able to generate the amps necessary to run a lot of hungry electrical appliances. To combat the problem, Smith has elected to use RV-type propane/12-volt/110-volt refrigerators. These are well suited to multihulls because they work most efficiently when level. LPG, of course, will be the usual energy source for these units, though at the dock shorepower works well. We sailed with a Dometic three-way refrigerator for several years and found them too poorly insulated for 12-volt service.

An instantaneous gas-fired water heater services the Gemini’s shower, which again eliminates the need for electricity.

About the only appliances that must then be accounted for are cabin lights, fans, stereo and pumps. This can be handled by several good quality batteries, though some owners note the need for alternate energy sources. Solar panels, in our experience, can help a great deal, but several fairly large ones will be needed. They are difficult to place where shadows won’t limit performance, and where they aren’t likely to be stepped on. Plus, their life expectancy is depressingly brief—several years in our experience. A better bet, for many cruisers, will be a pole-mounted wind generator capable of producing, say, six to seven amps in 15 to 18 knots of wind.

Conclusion

The Gemini 31 is a comfortable coastal cruiser that benefits from its builder’s undying devotion. The quality of workmanship isn’t what you’ll find in more expensive monohulls or multihulls, but this is also one of the few cruising multihulls that’s affordable to buyers in the $50,000 to $80,000 range—used or new.