In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the names Charley Morgan and Ted Irwin were practically synonymous with Florida boatbuilding. Charley Morgan was definitely one of the designers and builders that shaped the early and middle years of fiberglass sailboat building.

Morgan designs from that period run the gamut from cruising houseboats—the Out Island series—to the 12 meter sloop Heritage, the 1970 America’s Cup defense candidate that Morgan designed, built, and skippered.

But before Heritage, before the Out Island series, Charley Morgan designed cruiser/racers to the CCA rule. His successful one-off boats were typified by Paper Tiger, Sabre, and Maredea. Early Morgan designed production boats included the Columbia 40 and the Columbia 31.

In 1962, Morgan Yacht went into business to build the 28′ Tiger Cub. In 1965, the company really got rolling, building the Morgan 26, the 36, and the 42. In 1966 the Morgan 34 was added to the line. It stayed in production until the 1972 model year, when it was phased out in preference to the Morgan 35, a slightly larger, faster boat which fit a little better into the new IOR racing rule.

The Morgan 34 is a typical late CCA-rule centerboarder. Charley Morgan specialized in this type of boat, which was favored under the rating rule and well-adapted to life in the shoal waters of the Florida coast and the Bahamas.

By today’s standards, the Morgan 34 is a small boat, comparable in accommodations to a lot of 30-footers. When the boat was designed, she was as big as most other boats of her overall length.

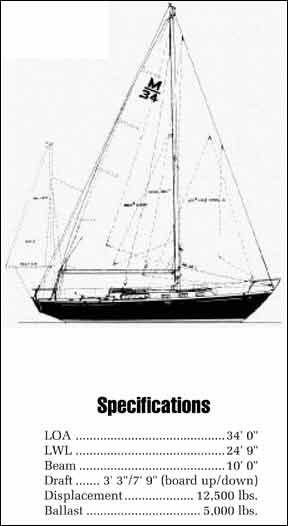

In profile, the boat has a sweeping, moderately concave sheer. The ends of the boat are beautifully balanced: the bow profile is a slight convex curve, the overhanging counter aft is slightly concave. Esthetically, hull shapes of this period from the best designers are still hard to beat.

Sailing Performance

With a typical PHRF rating of 189, the Morgan 34 is not as fast as some of the more competitive cruiser/racers of the same vintage, such as the Tartan 34.

With just a little more sail area than the Tartan 34, the Morgan 34 is about 1,300 pounds heavier.

Most owners rate the boat as about the same speed both upwind and downwind as boats of similar size and type. At the same time, the boat’s performance is at least as good as a lot of more modern “pure” cruisers of the same length.

The rig is a simple, fairly low aspect ratio masthead sloop, using a slightly-tapered aluminum spar, stepped through to the keel.

Although there are double lower shrouds, the forward lowers are almost in line with the center of the mast, with the after lowers well behind the mast. On a lighter, more modern rig, this shroud arrangement would just about require a babystay, but on the stiff masts of the late 1960s, it would be essentially superfluous.

Early boats in the series have wooden spreaders. Unless well cared for, they can rot. For some reason, wooden spreaders on aluminum masts tend to get ignored more than the same spreaders on wooden masts.

The boom is a round aluminum extrusion equipped with roller reefing. Roller reefing is tedious, inefficient, and usually results in a poorly-shaped sail. If we were to buy a Morgan 34 for cruising, the first thing we’d do would be to buy a modern boom equipped with internal slab reefing.

Shroud chainplates are located right at the edge of the deck, so inboard genoa tracks would just about be a waste of time. The spreaders are short enough that you can sheet the genoa just inside the lifelines when hard on the wind.

Just about every piece of sailhandling equipment you’d normally expect on a cruiser/racer was an option on this boat. You may find extremely long genoa tracks—some boats originally carried 170% genoas, which were lightly penalized under the CCA rule—or you may find very short genoa tracks. Likewise, turning blocks, spinnaker gear, and internal halyards were all options.

The original jib sheet winches were Merriman or South Coast #5s. Compared to modern winches, they are slow and lack power. For anything other than casual daysailing, you’ll want to upgrade to modern two-speed self-tailing winches for the genoa.

At the aft end of the cockpit, there is an old-fashioned flat mainsheet traveler track. Although this isn’t a bad arrangement for a cruising boat, it would be tempting, while replacing the boom, to install a modern recirculating ball traveler. You could then keep the boat on her feet a little better close reaching in a breeze by simply easing the traveler car to leeward without slacking the mainsheet.

With the standard tiller, the mainsheet location is a bit of a problem, since the helmsman sits almost at the forward end of the cockpit. This is fine for racing, when the helmsman does nothing but steer, but it is awkward for shorthanded cruising.

Like a lot of boats with low aspect mainsails, the Morgan 34 tends to develop weather helm quite quickly as the breeze builds. Despite a 40% ballast/displacement ratio, the boat is not particularly stiff. She is narrow, and the shoal draft keeps the vertical center of gravity quite high.

The boat is quite easy to balance under sail in moderate conditions, thanks to a narrow undistorted hull, a long keel with the rudder well aft, and a centerboard. Owners report that on wheel-steered boats, you can tighten down the brake and the boat will sail itself indefinitely upwind.

Engine

Standard engine in the Morgan 34 was the Atomic 4 or the Palmer M-60, both gasoline engines. Perkins 4- 107 and Westerbeke 4-107 engines were $2,000 options.

If you can buy a used boat cheaply enough and plan to keep it for a few years, it would be a natural candidate for installation of one of Universal’s new drop-in Atomic 4 diesel replacements. However, since a new diesel would cost about 25% of the total value of the boat, such an upgrade is not something to be taken lightly.

With the side-galley interior with quarterberths aft, engine access for minor service is reasonable through panels in the quarterberths.

Engine access is less straightforward with the aft galley arrangement, requiring removing the companionway steps just to get to the front end of the engine.

Almost unanimously, owners in our survey state that the boat is next to impossible to back down under power in any predictable direction. With a solid two-bladed prop in an aperture, reverse efficiency is minimal with no prop wash over the rudder.

A 26-gallon Monel fuel tank was standard. Monel, an alloy of copper and nickel, is one of the few tank materials that serves equally well for gasoline, diesel oil, or water. It is prohibitively expensive, and is therefore rarely used for tanks in modern production boats. You may also find a Morgan 34 with another, optional, 15-gallon fuel tank.

Construction

In the late 60s and early 70s, Morgans were of pretty average stock boat quality. Glasswork is heavy, solid, and unsophisticated.

The construction is a combination of good features, coupled with corners cut to keep the price down.

Through hull fittings are recessed flush to the hull—good for light air performance—yet gate valve shutoffs were standard. Believe it or not, you could buy bronze seacocks as options for about $5 to $25 each! That’s what we call cutting corners.

Lead ballast is installed inside the hull shell. The classic drawback to inside ballast is the vulnerability of the hull shell to damage in a grounding.

The cockpit is very large, larger than desirable for offshore sailing. In addition, there is a low sill between the cockpit and the main cabin, rather than a bridgedeck. You can block off the bottom of the companionway by leaving the lower dropboard in place, but this is not as safe an arrangement as a bridgedeck. Cockpit scuppers are smaller than we would want for offshore sailing.

Molded fiberglass hatches are in most cases more watertight than badly designed or maintained wooden hatches, but they are almost never as good as a modern metal-framed hatch. They’re simply too flexible. When the seals get old, you tend to dog the hatch tighter and tighter, further compressing the seals and putting uneven pressure on the hatch cover. The result is almost always leaking. Leaking hatches may seem like a small problem, but they are like a splinter in your finger: the pain and nuisance are all out of proportion to the item inflicting the injury.

Like many centerboards, the Morgan 34’s can be a problem. The original board was a bronze plate weighing about 250 pounds. When fully extended, the bronze board is heavy enough to add slightly to the boat’s stability. Later boats have an airfoil fiberglass board of almost neutral bouyancy. There’s a lot less wear and tear on the wire pennant with the glass board.

You may find a Morgan 34 that has been owner-finished from a hull or kit. Sailing Kit Kraft was a division of Morgan, and you could buy most of the Morgan designs in almost any stage of completion from the bare hull on up.

A kit-built boat can be a mixed blessing. If you find a boat that was finished by a skilled craftsman, it could be a better boat than a factory-assembled version. On the other hand, it could also be a disaster. Since the quality control of a kit boat is monitored only by the person building it, an extremely careful survey is required.

No matter how well executed it may be, an owner-completed kit boat rarely sells for more than a factory-finished version of the same boat. Most buyers would rather have a boat with a known pedigree, even if the pedigree is pretty average.

There’s a decent amount of exterior teak on this boat, including the cockpit coamings, toerail, grabrails on the cabin, drop boards, hatch trim, and cockpit sole. Check the bedding and fastening of the cockpit coamings carefully. If you want to varnish coamings that have been either oiled or neglected, it may be necessary to remove and rebed them.

Exterior appearance of older boats such as the Morgan 34 is greatly improved by varnishing the teak trim. It particularly spiffs up boats with the faded gelcoat that is almost inevitable after 20 years of use.

The standard Morgan 34 was a pretty basic boat. There were single lifelines, a single battery. There was no sea hood over the main hatch, and no electric bilge pump. Most boats left the factory with a fair number of options, but you may not find a lot of things that would be standard today.

In general, the construction and design of the Morgan 34 are suited to fairly serious coastal cruising. We would not consider the boat for offshore passagemaking without improving cockpit scuppers, companionway and hatch sealing, cockpit locker sealing, and bilge pumps.

Interior

The Morgan 34 dates from the heyday of woodgrained Formica interiors. Woodgrained mica bulkheads are even more lifeless than oiled teak bulkheads. However, mica makes a pretty decent painting base if it is thoroughly sanded so that all traces of gloss are removed. Freshly-painted white bulkheads with varnished trim would make a world of difference in the interior appearance of this boat.

The interior trim on a lot of Morgan 34s is walnut, which is a pretty drab wood, even when varnished. For an extra $400 or so you could get teak trim. Unvarnished teak and walnut are very similar in appearance, although walnut is usually a bit darker.

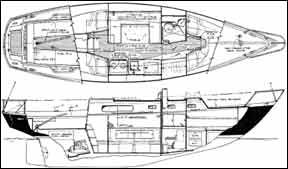

The forward cabin contains the normal V-berths, with a drawer and bin below on each side. A stainless steel water tank fills most of the space under the forward berths. The standard tank holds 30 gallons, but many boats have the optional 60-gallon tank.

A fiberglass hatch provides fair-weather ventilation for the forward cabin. A double-opening hatch was optional, as were opening ports in place of the standard fixed ports. Below the hatch, headroom is just over 6′.

The head compartment on the port side is quite cramped when the door is closed. However, it almost doubles in size if you close off the forward cabin with the dual-purpose head door, then close the sliding pocket door that separates the forward passageway from the main cabin.

Unfortunately, this pocket door is particle board, and it is likely to be a mushy mess, since any leaks around the mast drip right onto the door. “Waterproof” particle board found its way into a lot of boats in the 1960s and early 1970s. It shouldn’t have.

A shower installation was optional, and added about $800 to the base price of the boat for a pressure system, sump, pump and water heater. It is a desirable option if you plan on cruising.

You will find three different main cabin layouts. All were available as no-extra-cost options. In the most common layout, the galley occupies the starboard side of the main cabin, with a dinette opposite. This arrangment was fairly common in the late 1960s and early 1970s. You either love this galley/dinette arrangement or you hate it. Having spent a fair amount of time sailing offshore with a similar layout, we can say unequivocally that we hate it.

With the modern U-shaped galley, the cook can stand in one place and reach everything by simply turning around. With a linear galley, the cook has to take several steps to move from the icebox to the stove. This is fine when the boat is tied to the dock, but offshore it means that there’s no way the cook can wedge himself or herself in a single secure location while preparing meals.

A dinette also presents problems under way. Offshore, the most secure way to eat is to sit on the leeward settee, holding your plate in your lap. Unless there is a settee opposite the dinette, half the time you’ll be sitting on the uphill side of the boat while you’re trying to eat. This may be good for weight distribution while racing, but it’s not very secure. We’ve seen more than a few bowls of beef stew go flying from the windward to the leeward side of the main cabin when the boat took a knockdown.

Two different aft galley arrangements were options. In one, the dinette is retained, with a settee opposite. In the other, the dinette is replaced by a settee and pilot berth.

Choosing between these two is purely a matter of taste. The pilot berth layout gives three sea berths in the main cabin. On the other hand, the dinette table can be lowered to form a double berth.

The aft galley is larger than the side galley. To port, there is a gimballed stove, a large dry well, and outboard lockers. A sink, icebox, and other lockers are located on the starboard side.

Reduced access to the engine is the only disadvantage we see to the aft galley layout.

In common with a lot of boats of this period, the electrical panel is inadequate for the amount of goodies that are likely to have been installed in the boat over its life. The panel is also located in the worst possible place—directly under the companionway hatch.

With the aft galley, a good location for the electrical panel would be outboard of the sink tucked under the side deck. In all likelihood, you’re going to sacrifice that galley storage space to install navigation electronics anyway, since the top of the icebox is the only reasonable space to use as the chart table.

That’s right, there’s no nav station in this boat: we’re talking the late 1960s, when a boat with a radio, a depthsounder, and a knotmeter was heavily equipped with electronics.

There is reasonable storage space throughout the boat. Space under the settees is not taken up by tankage.

Headroom is 6′ 3″ on centerline throughout the main cabin, falling off to about 6′ at the outboard edge of the cabin trunk. All the berths are at least 6′ 6″ long, and they are proportioned for normal-sized human beings.

Decor in the main cabin is decidedly drab, between woodgrain laminate bulkheads and a sterile white fiberglass overhead liner. The original upholstery was vinyl, completing the low-maintenance theme. Paint, varnish, and nice fabric cushions would make a Cinderella of an interior that is reasonably roomy, laid out well, and uncluttered.

Ventilation in the main cabin isn’t great. There’s no overhead ventilation hatch, although there’s room to install one. Once again, the stock two small fixed ports may have been replaced with optional opening ports—a plus, but a small one.

A single long oval fixed port on either side of the main cabin gives the boat a very dated look. It would be tempting to remove the aluminum-framed port and replace it with a differently-shaped smoked polycarbonate window mounted on the outside of the cabin trunk and bolted through. We’d make a number of different patterns out of black construction paper and overlay them on the outside until we found a pleasing shape. You’d be surprised at how this would dress up appearance.

Conclusions

The Morgan 34 is similar in design and concept to the more-popular Tartan 34, which dates from the same period. By comparison, the Tartan 34 is lighter, faster, and has less wetted surface, since it lacks the Morgan’s full keel. As a rule, we prefer the Tartan 34’s construction details, although Morgan owners report somewhat less gelcoat crazing and deck delamination.

In 1970, the Morgan 34 and the Tartan 34 were almost identical in price. Today, however, the same Tartan 34 will cost about 20% more than the Morgan 34. Part of that difference in price stems from the fact that the Tartan 34 is less dated in appearance, design, and finishing detail.

If you want a keel/centerboarder for cruising in shoal waters such as the Bahamas, the Gulf of Mexico, or the Chesapeake, but don’t want to spend the money for the Tartan 34, a Morgan 34 is a good alternative. With effort and money, you can upgrade the Morgan 34 quite a bit. As always, however, you should compare the dollars and amount of time invested before getting involved with a boat that dates from a period when the aesthetics of hull design were light years ahead of the nitty gritty of detailing and interior design.

There is a Morgan 34 for sale at a good price in good condition, but it needs a mast. How much and where can I get a reasonable mast?

Roger

I may know. Plus I have a 34 Morgan, I may sell at a very reasonable price, with dockage.

Great report on this boat! I bought this boat about a year ago without seeing it in the water I have no idea on how it performs. This write up gives me some points of interest. I am %80 through a refit and have updated a lot mentioned in this article. I can’t complain as I got the boat with a Westerbeke in it for well less than 10k. The plan is to use it to curcumnavigate an island in the North Atlantic starting in 2023. Watch “FRILL” on youtube coming soon!

Hello sailors! I own a Morgan 34 and am trying to find where the holding tank is and the seacock associated with it. Can anyone help?