Modern anchors of the recommended size that are set and rigged properly offer plenty of holding power in good sand or mud. Except for a horrible storm in an exposed location, you won’t hear about dragging unless the bottom is poor. In bad holding ground, however, all the holding figures you see quoted go out the window.

Between testing and cruising, we’ve experienced our share of dragging incidents, and have documented much of it. We frequently anchor over poor bottoms or with undersized anchors, with the intention of pushing boundaries, revealing differences, and observing failure modes. With the exception of awful setting practices, woefully undersized anchors, and a very few inferior designs, anchors drag for one of three reasons: a bad bottom, excessively short scope, and extreme yawing or surging, in that order.

Short scope is easy to solve (see “Short Scope Anchor Test,” PS November 2017). Extreme yawing and surging are solvable (see “Yawing and Anchor Holding,” PS February 2020). That leaves bad bottoms as the most common and challenging risk to identify and overcome.

Properly deployed on a good bottom, a properly sized anchor of modern design will reliably hold up to storm conditions (though probably not hurricane conditions). Proven older anchors like authentic CQR or Bruce anchors also do well, although they may require a little more weight and be less tolerant of poor technique. They also do not adapt as well to the full range of bottoms.

We dive on many of our cruising and testing sets, to see how well an anchor buried, and also after dragging, to determine why it failed. Nearly all of the poor results have been caused by a troublesome bottom that prevented the anchor from developing a strong grip.

The failure could be a bottom problem, or because the tip skewered a lone bit of trash. Blue water sailors can often visually preview the bottom, but brown water sailors are restricted to how it feels during the anchor drop and setting, and what the chart says.

In this report we examine which bottoms cause trouble, how we can spot them, and what we can do—if anything—to help our anchor grab and set.

CORAL

Island harbors are full of the coral, alternating with sand patches or uncertain depth and quality. A conscientious sailor will avoid anchoring in coral, a critical and vulnerable habitat for sea life.

PROBLEMS

• Damage to precious coral. Not just the anchor, but also the swing of the rode.

• Rode fouling.

• Chafing rope rode.

• Fouling of the anchor.

• Poor holding. Coral sand is not cohesive and it can be a thin layer over hardpan.

HOW TO IDENTIFY

• Coral grows in clear water, so most anchorages you can see it. An elevated perch offers the best view for spotting.

SOLUTIONS

• Take a mooring, if available.

• Look for open sand patches of sufficient size to allow for swing.

• If coral heads are scattered, buoy the rode. The buoys should float high enough to keep the rode away from coral in light wind, but immerse when the wind rises, so that achieving the ideal rode angle is still possible.

• Set hard, with sufficient thrust to confirm the sand is deep and secure.

ROCK

These can be broken rock and boulders. Like coral, there is high risk of the rode fouling on a rock, and uncertain holding in the surrounding areas. Many of the solutions are the same as they are for coral.

• Manually setting the anchor in a hole can work, but if the wind shifts, all bets are off.

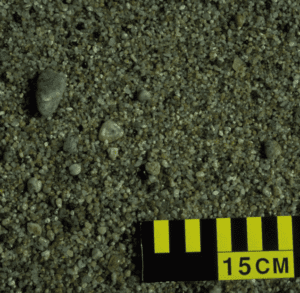

• Cobbles. This can be loose shingle- like cobbles, or compressed, which

behave more like hardpan.

PROBLEMS

• Cobbles roll, resulting in poor holding.

• Shingles may simply deflect the tip.

• Large stones may jam in the roll bar.

• The anchor cannot set in the conventional sense, because it cannot penetrate the loose stones.

• Gravel is a subcategory. If it is not mixed in with enough fine sand, the anchor will not dig and holding is poor.

• The anchor cannot tolerate any uplift; the rode must stay on the bottom, requiring very long scope.

HOW TO IDENTIFY

• Feels hard when the anchor strikes.

• Anchor comes up clean.

• Anchor drags and the rode pulses as the cobbles move.

SOLUTIONS

• Move. Reliable holding may be impossible.

• Often good holding clay and sand lie just beneath the cobbles or gravel. A larger anchor may reach through the cobbles and penetrate into finer material.

• In-line tandem anchors (see “Doubling Up: Full Size Tandem Anchoring” PS September 2016) may increase hold by 2 times, but still won’t set. Very long scope is required so that the rode cannot lift off the bottom, even for a moment (chain lift will takes weight off the lead anchor). Scope should be a minimum of 8:1 for chain, and a minimum of 20:1 for rope.

ROCK (HARDPAN)

Classified as rock, hardpan is sedimentary rock, impenetrable clay or very hard sand, or fossilized coral. It is often disguised by a thin covering of loose sand. A layer of loose shells over hard sand can behave like rock or hardpan. In rare cases, there may be softer ground below.

PROBLEMS

• There is nothing for the anchor to catch on.

• Cannot set because the anchor cannot dig.

HOW TO IDENTIFY

• Feels hard when the anchor strikes.

• Anchor comes up clean, or very little sand. Nothing on the roll bar.

• May feel set at first, but then drags at medium throttle.

• Shank and roll bar not buried. If you poke around in the furrow behind the anchor with a screwdriver you will feel the hard bottom.

SOLUTIONS

• If the hard pan is very hard sand or stiff mud, a sharp point on the anchor will help, often a lot. Consider sharpening the anchor; yes, you will remove galvanization from a small area, but it generally does not last on a sharp toe anyway. The corrosion will rub off every time you use it.

• In-line tandem anchors. As with cobbles, more chain is simply increasing bottom friction. However, if there are scattered rocks for an anchor to grab, in-line tandems have better odds of snagging something and holding. In-line tandems should be used only when burying the anchor is not possible.

OOZE

Ooze is very soft mud, only softer. It is often high organic content, resulting in better holding in colder temperatures, then less in the summer, when the water gets warm, and slimy creatures proliferate.

PROBLEMS

• Like anchoring in pudding or liquid peat moss.

• Very poor holding. Also commonly littered with debris that can foul the anchor and block deep burying.

• Easily liquefied by yawing. Instead of becoming more secure over time, holding may decline when yawing starts.

• Roll-bar anchors might uselessly settle upside down in ooze, since the bottom is too soft for the anchor to self-right.

HOW TO IDENTIFY

• Runny mud on the anchor.

• Can’t really feel the bottom when the anchor strikes, because it does not hit so much as just slow down.

• Trash and sticks may come up with the anchor.

SOLUTIONS

We explored this in detail in 2020 (see “Mud Anchoring Wisdom,” PS August 2020).

• Try a pivoting fluke anchor, such as a Fortress. Be certain the anchor has mud palms (standard since 1994). Setting in ooze requires a few tricks. Because the shank can settle in the ooze, resulting in a fluke-up orientation that makes setting impossible, get a very light set as soon as possible; just enough to point the flukes downwards. Use only light chain; more weight makes the shank sink faster, and cable or even Dyneema can be better (see “High Tech Anchor Rode,” PS August 2018).

• A slightly oversize anchor can help, but even standard size will bury very deeply in strong winds (and may be very difficult to recover). Conservative anchor sizing or over-sizing helps on most bad bottoms, but with pivoting fluke anchors (Danforth, Fortress, etc.), stick with the manufacturer’s recommendation. An oversized pivoting-fluke anchor might not bury as deeply, and unless the whole anchor (including the cross-stock) is fully buried, it is prone to tripping or flipping over in a wind shift. If this happens and the flukes are clogged with mud or debris, the flukes might not flip over to the new position. In soft bottoms, we recommend using an oversized pivoting fluke anchor only when you expect strong winds from a consistent direction.

• Use another type of oversized anchor. In soft mud, double the weight can double holding, but it is still pretty weak until the anchor penetrates to the better clay underneath. Then very good holding is possible.

• Let it soak. Very light set, wait an hour while the ooze consolidates around the fluke, then set moderately, then wait, then really pull. See “Mud Anchoring Wisdom,” August 2020.

• V-Tandem anchoring can greatly increase security, but careful rigging is required to avoid rode fouling and to get the most from it in shifting wind conditions (see “Tandem Anchoring,” PS August 2016).

• Deploy carefully, so that the anchor lands right side up. A light float, such as a small net float, will land it right side up without affecting holding (mass matters less than fluke area in ooze) but this can also foul the rode if the wind or tide rotates.

RIVER SAND

Round, river-sand grains flow easily into and through tight crevices, making them a great proppant for a fracking operation, but iffy for anchoring.

PROBLEMS

• Anchor holding is poor because the round grains flow right around your anchor.

• The anchor won’t bury deeply.

• Easily liquefied by yawing.

HOW TO IDENTIFY

• Sand that won’t pack.

• Runs right off the anchor.

SOLUTIONS

• Use a large anchor.

• Reduce yawing by all practical means.

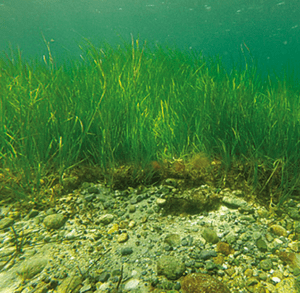

WEEDS

Sea grass is important habitat (often protected by law) and holding is deceptively poor.

PROBLEMS

• Can feel like a hard set, but often you are only held by a root bundle. When the wind increases the roots fail but leave the anchor fouled so that it cannot reset.

• Dense weed prevents the shank and rode from burying. Only the fluke sets.

HOW TO IDENTIFY

• Darker areas, even in muddy water.

• Weed on the anchor fluke.

SOLUTIONS

• Move.

• Sharply pointed anchors have the best chance. Avoid broad anchors (Bruce-type) because they cannot penetrate and plows (CQR-type) because they tend to just lie on their sides and fail to take hold.

SLOPE

Setting on a steep slope can reduce scope to zero if the chain is deployed downslope.

HOW TO IDENTIFY

Chart shows change in depth greater than 1-foot per 100 feet.

PROBLEMS

• Geometry reduces scope. Only important if the slope is very steep, at least 1:20, like the edge of a channel.

• Hard. Often the bottom is impenetrably hard, because it is scoured by current and anything soft has eroded away. If it is soft, it is likely unconsolidated sediment of high organic content from seasonal rains, making it weak with very little resistance to shear.

SOLUTIONS

• Move. If it is near a channel you probably should not be there.

• Second anchor pulling the boat up-slope or cross-slope. Often the reason to anchor near a drop off is because the waterway is narrow. This is the ideal case for either fore-aft anchoring or a Bahamian moor anchoring.