Sailors gaze longingly at the rope wall at the local chandlery, coveting rope made from exotic fibers that promises ultra-low stretch and light weight, perfect for every halyard, sheet, and running-rigging application. But are they really? Certainly, there must be applications where a little stretch is a good thing, perhaps the best thing.

We prefer nylon rope for anchor rode and dock lines, where it absorbs energy that would otherwise strain cleats. We like stretch in safety tethers, where it makes sudden stops survivable. We like nylon for spinnakers, where it dampens opening shock and the effects of gusts and rolling. And weve found one more use for an elastic line.

Photos by Drew Frye

The 34-foot PDQ catamaran owned by PS tester Drew Frye and used for an endless array of experiments came from the factory equipped with the ubiquitous polyester double-braid traveler line, just like every other boat Frye had ever owned. Over time, the polyester double-braid became tattered, and when a length of Spectra double braid became available-surplus from other testing-he thought it might make a nice upgrade. But he was dead wrong.

If any slack developed in the traveler line during a jibe, even in light winds, it felt and sounded as though the boom had come up against a concrete wall. In a breeze, it demanded strict vigilance to avoid ripping fittings and breaking blocks.

Frye knew the low-stretch rope had to go, but what would he replace it with? Going back to the original polyester seemed like a sensible choice, but what if the new rope had even more elasticity? Would that help dampen loads, perhaps extending the life of hardware?

A length of retired dynamic ice-climbing rope was the solution. We had read that bluewater voyager and Practical Sailor contributor Evans Starzinger had successfully used 10-millimeter climbing rope as a traveler line across oceans. And while armchair sailors pronounced the practice unseaman-like, Starzinger explained that he was reporting on proven practice, not theory.

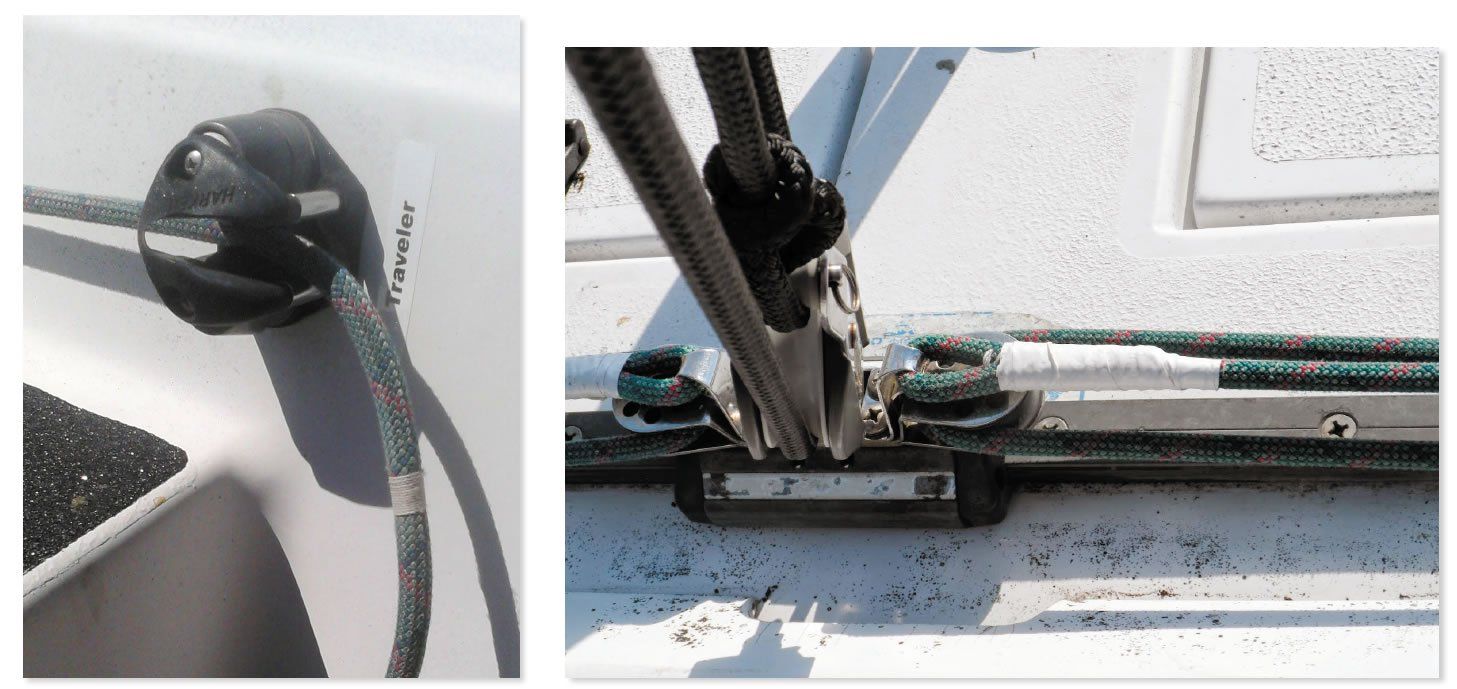

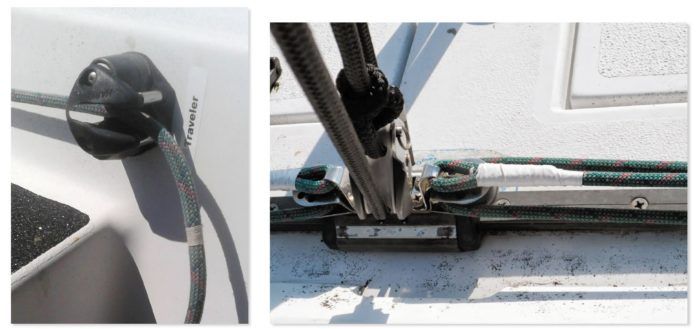

Frye settled on 8-millimeter ice-climbing line for his catamaran, and found it to be a perfect fit. While he still carefully controls the traveler line in windy weather, minor errors in moderate weather and flying jibes in light winds have become causal and quiet.

Weve discussed this with a number of professional riggers and found a few that like and recommend nylon rope for traveler lines. Before going out and buying just any climbing rope, however, it is good to know what youre getting into.

Climbing Ropes

There are five common types of rock-climbing ropes that fall into two categories: dynamic ropes and static ropes. Dynamic ropes are suitable for traveler lines, depending on the size of the boat. In climbing, they are used where controlled stretch is required to absorb fall energy. With a nylon-braid cover over a parallel nylon core, they are rated by repeated severe test falls and not by strength. The cover is very tight to reduce snags on rocks. This makes them very difficult to splice, but they knot very well. To provide non-rotational behavior under extreme dynamic loads, 50 percent of the core strands are righthanded, and 50 percent are lefthanded.

Static ropes are low-stretch, polyester braid over polyester parallel core. The low stretch reduces abrasion and makes ascending and hauling more efficient. However, because of slight differences in design, polyester yacht braid is a better choice for every boat application. Like dynamic ropes, the tight cover-used to reduce snags on rocks-makes these very difficult to splice, and knots wind up being quite bulky.

The following are the five main types of climbing rope; three are dynamic, and two are static.

Single dynamic ropes: These rope diameters typically range from 8.8 to 11 millimeters and are used alone by rock climbers. They are tested to survive at least five worst-case scenario falls singly (i.e. used alone).

Half dynamic ropes: These rope diameters are typically between 7.2 and 8.3 millimeters, and are used in pairs by rock climbers and ice climbers. Although they are strong enough to catch a few falls singly, they are used in pairs to provide greater reliability against cutting.

Twin dynamic ropes: These ropes typically run from 7.2 to 7.7 millimeters and are used primarily by ice climbers. They are always used in pairs to reduce the chance of chopping with an ice axe.

Single static ropes: Typically 10 to 12 millimeters and used singly for ascending and rappelling. They must be used without slack, since they cannot absorb fall energy. They have a 5,000-pound minimum strength.

Accessory cord: These range from 5 to 8 millimeters. The construction is identical to static single ropes, but the ropes are smaller, used for climbing anchors and hauling gear up cliffs.

Observations

We wondered if the shock-absorbing characteristics of the nylon climbing rope would last, and so far, it has. Another concern was how elasticity impacts mainsail set. A racer might prefer less stretch, but Frye hasn’t noticed any worse performance on his cruising cat.

Chafe can be a problem if the cleats are rough or tackle poorly designed. Climbing ropes will chafe more easily because they have a proportionately thinner cover and thicker core, since most shock absorption is achieved in the core.

In field testing, dynamic line wears slightly faster than polyester double-braid, depending on the cam cleats used and on rigging. If the line is winched, the line will need to be 11 millimeters. If something even larger is needed, consider nylon double-braid. The nylon will have only about half the stretch of dynamic climbing rope, but it will offer better abrasion resistance, making it a viable compromise.

Stretch on Fryes dynamic traveler is typically about 1 to 2 inches under sailing loads, with as much as 3 to 4 inches during rough jibes. Expect to see the traveler work up and down 1 to 2 inches in a strong wind when going to windward; this hurts nothing, even helps spill some air from the mainsail during the gusts.

To take full advantage of the shock absorption, the traveler must stay off the end stops during jibes. Mark the line to leave about 4 inches of cushion. After the jibe is complete, the traveler can be eased down against the stop and a preventer can be rigged.

Fryes success with the traveler line led him to ponder other possible uses for climbing rope. He tried it out for dock lines and anchor rode for small boats, but he doesn’t recommend it for larger boats. As a dockline, it clearly had less abrasion resistance than nylon three-strand or double-braid. And as anchor rode, it was incompatible with the rope/chain gypsy in Fryes windlass, was very difficult to splice, and was not as abrasion resistant as three-strand or double-braid.

There are always stories of folks using climbing rope for a mainsheet or a towline, but that does not make them suitable for the purpose.

Conclusion

Retired climbing ropes have typically seen very little ultraviolet light, have been pampered, and are retired when barely broken in so there is often a lot of good used line laying around. The most available are 10 to 11 millimeter rock-climbing ropes. The smaller 7- to 8-millimeter lines appropriate for hand-tensioned travelers on many boats are designed for ice climbing and are a bit more scarce. However, both can be purchased used online by the meter. Eight-millimeter line is also available from most climbing stores in 20-meter lengths.

Bottom line: If you would like softer jibes and an easy hand, give dynamic ice-climbing rope a try. Though it may wear a little faster than yacht braid, the quiet, easy hand, and reduced impact on hardware may be worth it.

Good article. However, I wonder if the 8mm dynamic line would work even better using a figure 8 boom brake?

Thanks,

Gary Hattan