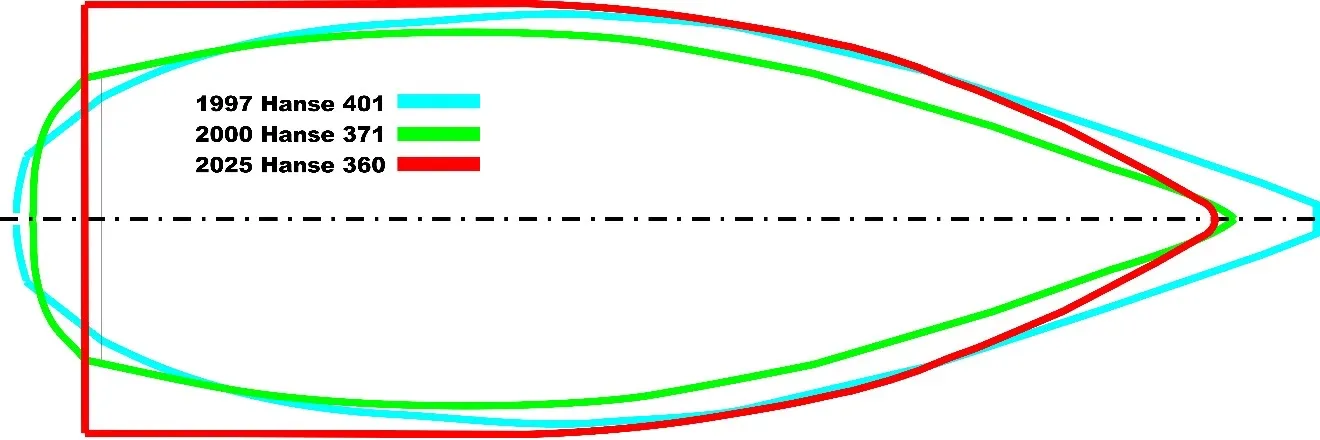

If you pay even the slightest attention to the shape of the sailboats on the water, in marinas, or at boat shows, you are sure to have noticed that transoms are getting wider. much wider. To illustrate this, I compared the outlines of three models from the respected German builder HanseYachts AG.

Hanse 401

This model was introduced in 1997 but based on the 1980s Joubert and Nivelt designed Bianca 420. Hanse chopped a couple of feet off the stern, making the transom more upright and a bit wider. This boat is, to my eyes, the best looking of the three models. It has a shapely hull, with moderate overhangs and a graceful sheer.

Hanse 371

This was Hanse’s first commissioned design, from the America’s Cup winning team of Judel/Vrolijk. I have hull number 92 of the series, so I am not quite a neutral party. I visited the factory before purchasing the 371 and also considered the 401 which was still in production. Although I liked the 401 very much, the 371 was less expensive and offered a larger aft cabin, due to—you guessed it—a wider transom. The 371 was a modern design back then, with a near plumb stem, flat bottom, and a deep cast iron fin with a lead bulb. Since this is my everyday boat, I can tell you she is fast and stiff, with a well-balanced helm. She can, however, sometimes pound coming off a wave in rough conditions.

Hanse 360

This is Hanse’s latest model in the size range. The 360 has just won the prestigious European Yacht of the Year award in the Family Cruiser category. Designed by the French team of Berret-Racoupeau, it shares many characteristics with boats from Beneteau and Jeanneau. Both ends are vertical, with a transom width the same as the maximum beam. Despite the name, it is slightly less than 35 feet long on deck. However, if you look at the deck outlines, you can see that the 360 is a bigger boat than the 401 and the 371.

When you look at the planforms, the difference between the 401 and the 371 is subtle and evolutionary. The 360 is radically different. The bow is much fuller, and from midships aft it is just a box. In three dimensions, the first two look closely related. The 360 looks like something from another planet. This is a little misleading as Hanse had several intermediate models along the way to the 360 which got progressively fatter and broader sterned.

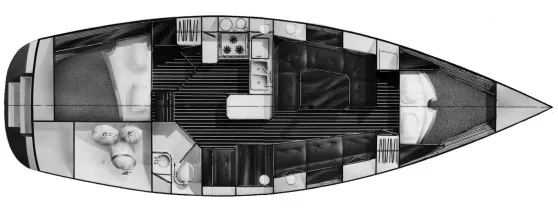

Because of the very wide stern, a single wheel would not work well on the 360, since the helmsperson would not be able to reach the sheets or see forward. Thus, the currently popular twin wheels have been adopted. This allows convenient passageway between them.

| Hanse 401 | Hanse 371 | Hanse 360 | |

| Year introduced | 1997 | 2000 | 2025 |

| Length on Deck | 39′-4″ | 37-0″ | 34′-8″ |

| Length WL | 34′-4″ | 32′-3″ | 33′-9″ |

| Beam | 12′-9″ | 11′-8″ | 13’-1″ |

| Displacement | 18260 lb. | 15,200 lb. | 17,200 lb. |

| Ballast | 7150 lb. | 4950 Lb. | 3975 Lb. |

| Sail Area | 800 Sq. Ft. | 705 Sq. Ft. | 656 Sq. Ft. |

| Transom width | 6′-8″ | 8′-7″ | 13′-1″ |

| Sail Area/Displacement | 18.45 | 18.40 | 15.75 |

| Sail Area/Disp. Genoa | 21.97 | 22.30 | N/A |

| Displ./Length | 202 | 201 | 200 |

| Ballast Ratio | 39% | 33% | 23% |

| Beam/ Length % | 32% | 32% | 38% |

| Transom % Beam | 52% | 73% | 100% |

History of Transom Design

The evolution of sailboat transoms has followed that of motorboats. Viking ships had no transom, they were the same at both ends. That shape suits a low level of motive power, such as oars. In the early days of small motorboats, the double-ended shape was used to slip along at low speeds. As more powerful engines were installed the narrow sterns squatted deeply as speed increased. The transom stern allowed more buoyancy aft. As power increased sterns got wider and wider until they equaled the maximum beam, just like the Hanse 360. They didn’t just get wider, they got deeper as well, until on very fast boats, the bottom of the transom was underwater.

Transom Design and Performance

We have seen the same trends in offshore racing sailboats which now achieve motorboat speeds. They are true planing hulls with wide sterns and immersed transoms. A heavy cruising boat such as the Hanse 360 is unlikely to plane, although it might surf in a big following sea. In light winds the large wetted surface and relatively small sail area will make her slower than her predecessors.

Sail area to displacement ratio is the usual measure of light air performance. The table above shows that number, but in this case, there is an important additional factor. Because of the outboard chainplates on the 360, it cannot fly an overlapping genoa effectively. The 401 and 371 both have inboard chainplates allowing a narrow sheeting base for genoas up to 150%. I added a row to the table which shows the SA/D ratio with a 150% genoa. With that sail, the Hanse 371 has the most power in light air. Since I race my own boat regularly, from experience I can say the genoa adds as much as a full knot of speed upwind in true winds of less than 6 knots. It takes about 12 knots true for the working jib to equal the genoa in upwind capability, and the genoa is always faster reaching.

It is safe to say that both the 401 and 371 will be faster upwind than the 360, in pretty much any condition. It is worth mentioning that although all three boats are fractionally rigged, only the 360 has a masthead halyard for the spinnaker or code zero sail. This gives it a spinnaker area as big or bigger than the 401, so it might be faster downwind. A code zero could also make it fast reaching, so the main advantage of the older designs would be hard on the wind.

Comfort

The motion of a heavy boat is usually slower and gentler than that of a light boat. But hull shape is more important. Boats known for a comfortable ride in rough seas are usually moderately heavy (D/L ratio of 250-300). They are typically neither extremely wide nor extremely narrow. Of the three Hanse models, the 401 is likely the most comfortable in a rough sea. At anchor, the situation is reversed. The wide beam and flattish bottom mean the 360 will probably roll less when anchored. The huge cockpit makes lounging at the dock and eating al fresco a pleasure. Swimming off the stern is enhanced by a large platform and step which cleverly folds away when not in use.

While I have focused on three boats from the same manufacturer, the trend is clear across the whole production boat industry. For the way most cruisers use a boat, the new, wider transom models have many advantages. The Hanse 360 with her self-tacking jib and high initial stability will be a doddle to sail in moderate conditions. If the wind drops light, most people start the motor, and the 360 has a good one, a smooth Yanmar saildrive, insulated against sound and vibration. The huge interior and exterior spaces and hull windows will be appreciated at anchor.

For myself, I can’t seem to find these newer designs pleasing to the eye. But judging by sales, most cruisers disagree, or more likely, don’t care.

Why Transom Shapes Vary

The biggest factor is the age of the boat. Older boats tend to have narrow sterns.

Racing Rules

This has more to do with racing rules than designer preference, safety or comfort. The old Cruising Club of America rule (CCA) tended to favor long overhangs, as it penalized waterline length. This resulted in graceful looking hulls, which were not usually particularly fast. Up to the 1970s most production racer-cruisers were influenced by this rule.

In the 70s and 80s the dominant racing rules favored boats with a wide midships beam and pinched ends, often resulting in small, V-shaped transoms.

After 1990 the IMS rule used a computer Velocity Prediction Program to estimate, with reasonable accuracy, the theoretical performance of a boat. In theory, this would allow fair handicapping of disparate hull shapes and rigs. Designers could now concentrate on the shape that met the client’s requirements best—whether speed, comfort, or interior space—with the assurance that it would be fairly rated.

This new design freedom resulted, at least initially, in clean-lined hulls with no measurement distortions to “fool” a rule. It also generated a divide between racing boats (using the IMS and ORC rating rules) and racer-cruisers, that generally use the PHRF rating system, in which somewhat arbitrary ratings can be adjusted by committee.

Transoms got wider and bow overhangs got shorter, to maximize hull speed. It was not lost on designers and clients that this also resulted in room for sizeable aft cabins, which cruisers loved.

In theory, the design of pure cruising boats should not be influenced by rating rules. But in practice, they always have been. On land, minivans have been supplanted by the sportier image of the SUV, even though in most cases it serves the same purpose, but less efficiently. So, rigs and styling were, and continue to be, influenced by whatever was popular on the racecourse.

Pioneering Designs

Wide transoms are not particularly new. In the early 70s, Vancouver BC designer Stan Huntingford produced the Maple Leaf 48, a cruising sailboat with a beam of over 15 ft. The transom was close to full beam and vertical. It featured a powerboat-like swim grid and a door in the transom. This 50-year-old design was far ahead of its time, and sold well, even though critics, including me, thought it ungraceful and ugly. It was a so-so performer under sail, but a big diesel bulled it along effectively under power. Oddly, there were few imitators at the time, and the line eventually died out.

Amazon 37

In 1983 I designed a round bilge steel boat called the Amazon 37 which was built to a very high standard by SP Metalcraft. It had a 12-foot beam and a wide, but not full beam, transom. To my eye, a big expanse of transom looked ugly. I came up with the idea of cutting recessed steps into the stern, The cockpit floor came right aft to the transom and drained through scuppers onto the steps. This eliminated cockpit drains and associated through-hull fittings.

The idea was popular with clients, and we sold several boats off the drawings. We displayed a finished boat at the 1984 Annapolis boat show, where it was widely admired. Among those who came aboard was Hank Hinckley, a man who knew something about boat building. He recommended the 37 to a friend looking for a steel boat.

The Amazon 37 was the only boat in the 1984 show with steps in the transom. In the 1985 Annapolis show I counted 17 boats with steps in the transom. One of them had steps identical in shape and dimension to ours. Coincidence? Sure.

Although we used the Amazon name long before Jeff Bezos, we never registered Amazon.com, since our company closed in the early 90s, before it mattered.

Bottom Line

Where is transom width going? It seems likely that it has reached its limit. Watch this space for something to come along that will prove me wrong.

Thanks for the interesting and informative read!

Thanks for the article, very informative. I wonder what is your opinion regarding sailing downwind in heavy weather with huge waves with a cruising crew. Something like cruising East to West in the Atlantic with winds above 30kts and big rollers. Which design is easier to steer the boat and which design is safer?

Thanks,

Gian Luca

I recall “sailing” my Krogen 42 trawler in the ocean in heavy seas with its bathtub rounded stern (almost canoe)… much better than a flat transom boat.

Excellent take on the subject, thanks a lot. Also, just a must nowadays is walk through transom with some shape for sitting a bit. Classical classical designs just are cumbersome, and already mentioned the aft cabin and storage.

The man who invented the sugar scoop! A single hander’s hero. On my Beneteau 343 I would back in with the midship line led to the stern gate, hop off and secure the line at the midship cleat, where I had left dangling the fore and aft lines so I could grab whichever end was drifting off. Thank you thank you!

You are far too kind to the pizza boats (shape). You do mention that the flat hulls are slower in light wind, which hardly anyone else mentions. However the flat ride at anchor seems a lot less useful when you consider the seasick inducing movement in even moderate winds. A previous poster asks about handling in heavy seas, and that is a very good point. Just think about the geometry and going down a wave at an angle, and which boat is more likely to broach or pitchpole.

Most current builders proudly proclaim the stiffness of their boats. However, there are two kinds of stiffness in a boat: the stiffness of its construction, and the stiffness of it sailing in the wind. You have pointed out that cruisers have borrowed a lot from racers, and not necessarily to their advantage. This is a case in point. Builders and their salesmen point to the wide stern and flat chines and say “this is a stiff boat,” as if that were a good thing in a cruiser. It’s a good thing in a racer that can plane— and as you point out most cruisers can’t and won’t. That sort of stiffness is good for speed, definitely not for cruising, because it means the boat will snap back-and-forth very quickly and barfily (new word) in a seaway.

Cruisers want stiffness in construction, and from touring the big selling names at boat shows I can say few are providing it. There is nothing wrong with a Beneteau (et al) on the bay or the sound and on the hook. They are perfect for lots of people. But they are not blue water cruisers nor are they racing boats. Why isn’t “ the perfect coastal cruiser” considered a marketable product?

I hope I run into you kicking around on the Georgia Strait. I owe you a lot.

Scott

Skyedancer, Vancouver

This was a absolutely great and fun read… I learned a lot.

As long as you stay close to land and can avert storms, this boat might be fine. But the wide beam and transom coupled with light displacement means that it will be prone to capsize, have a low range of positive stability, implying that once it capsizes it will turtle. In short, a nice boat at the dock to entertain, but don’t venture too far off the coast unless you like to live (or die) upside down.