Conversion Kits that Turn Your Boat’s Ice Box Into a Galley Refrigerator

Practical Sailor tested three kits that convert onboard ice boxes into full-fledged refrigeration systems. The three reefer conversion kits in the review-the Waeco-Adler Barbour Cold Machine (CU 100) from Dometic Corp., the Frigoboat Capri 35F by Veco SPA, and the Sea Frost BD-represent a cross-section of whats available on todays refrigeration conversion kit market. Testers looked closely at energy efficiency and the 12-volt units abilities to cool a small ice box with the least amount of amp hours possible. Testers looked at quality, details, reliability, and cooling capacity.

Shore-Power Boat Fire Protection

With the increased demand to have all the electrically powered comforts of home onboard, it should come as no surprise to boaters that the majority of AC-related electrical fires involve overheated shore-power plugs and receptacles. Prime Technology, aims to change all that with the introduction of its Shore Power Inlet Protector (ShIP for short), a monitoring and alarm device that automatically disconnects AC shore power when excessive heat is detected at the power inlet connector. We reviewed the ShIP 110 designed for use with a 110-volt, 30-amp system. The company also offers a similar unit (the ShIP 220) for use with 220-volt, 50-amp service. Charred plugs and receptacles are the result of resistance build-up (due to loose or corroded connections), which generates heat and the potential for fire, a problem especially prevalent among vessels that continually run high energy loads such as water heaters and air-conditioning units. In addition to monitoring the temperature of your vessels shore-power inlet plug and its wiring, the ShIP system automatically disconnects AC shore power when an unsafe temperature is detected, providing visual and audible alarms. (The audible alarm shuts down after five minutes to avoid prolonged disturbance to surrounding boats.)

Bluewater Sailors Review Tethers Underway

Practical Sailor had a chance to compare how three common snap hooks and three tether types function in actual use on a passage from Boston to Bermuda. Testers evaluated the pros and cons of elastic tethers and non-elastic tethers, double-legged tethers, single-leg tethers, the new Kong snap hooks, carabineer-style safety clips, and the Gibb-style clip. The Wichard elastic single-leg tether (nearly identical to our 2007 tether test favorite from West Marine, the West Marine 6-foot elastic tether with Wichards double-action hook at the deck end) was unanimously preferred over the non-elastic tether. Testers also preferred the Kong snap hooks over the others.

Six-Month Checkup: Long-Term Boat Wood Finish Exposure Test

Practical Sailor closes in on its search for the best teak oil, best marine varnish, and best synthetic wood finish this month. Testers check in on the 53 coated wood panels on our test rack, which have been enduring the elements for six months. Testers rated the panels for single-season gloss and color retention and coating integrity. The test products included dozens of one-part varnishes, two-part varnishes, synthetic wood finishes and stains, spar varnishes, wood sealants and teak oils from makers like Interlux, Pettit, Epifanes, Le Tonkinois, Minwax, Ace Hardware, Star brite, and West Marine. The long-term evaluation aims to find the best exterior wood finish based on overall ratings for ease of application, gloss integrity and appearance, and how the coating fares over time under real-world conditions. At the six-month mark, this report offers our single-season recommendations for finishing teak decks, cockpit trim, toerails, and other exterior wood surfaces.

Mailport: 05/09

In light of your recent letters on copper/epoxy antifouling bottom coatings, Id like to share my experience. Near the end of my Searunner trimaran boatbuilding project, I decided to apply a product known at the time as Copperpoxy. I applied the coating to all three hulls to about 20 mils thick, and then sanded this "orange peel" surface down to about 10 mils. I finished up with 220-grit sandpaper. In the end, it was beautiful. It was just like a perfectly smooth, new copper penny, and just a bit thicker than recommended. We started our cruising adventure in the foul waters of Beaufort, S.C. Very soon, I was doing a huge scrape job every week. The bottom was covered with grape-size barnacles. I noticed that the aft half of the main hull, the part with underwater metals, was fouling the worst. (I was changing zincs every week.) Two years later, in Pensacola, Fla., we decided to give up on this product and paint over it with Pettit Trinidad SR bottom paint. When doing the weeks-long prep for this painting, we could see that the skin of our epoxy/ply boat was electrically conductive and corroding all the way through in the entire area of the bonded shaft, strut, prop, gudgeons, and copper mast ground. We put on three coats of Trinidad, waited a few days, and splashed the boat. Within two weeks, the new paint had peeled off in the electrically active area. We re-hauled, stripped the paint in this area, and coated the problem Copperpoxy area with three coats of epoxy. After sanding and repainting, we set off for the Western Caribbean. Over the following six months, we noticed that even the epoxy would not stick to the Copperpoxy.

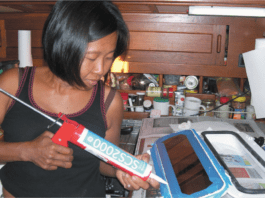

Eco-friendly Boat Maintenance

Practical Sailors May 2008 issue looked at green practices in marine maintenance outside the hull. This spring, we look at eco-friendly products and techniques for the boat interior. We focus on areas belowdecks where we can reduce our impact on the environment. Proper disposal of petrol fluids used in most inboard engines-fuel, lubricant oil, and transmission fluid-is paramount. Preventing engine fluid spills by using careful filling techniques is key, as are careful preparation for a possible spill and proper cleanup should a spill occur. The best products we found for preventing oil spills and cleaning up oil spills include 3M Sorbent Pads and MDR Oilzorb Engine Pads; Jabsco Oil-Changing System; and the Vetus Bilge Water/Oil Separator. We recommend RydLyme Marine and Barnacle Buster for a green descaling of a boats heat exchanger.Eco-friendly bilge cleaners that we recommend include CRC Industries Big Bully Natural Orange Bilge Cleaner, Clean Water Solutions Microbial Powder, Star brites Sea Safe Biodegradable Bilge Cleaner, and Star brites Super Orange Bilge Cleaner. Eco-friendly soaps and detergents recommended for green cleaning include Dr. Bronners Sal Suds and some cleaners in the Simple Green, Spray Nine, and Thetford Marine lines. And, don't forget plain old blue Windex.

Hope, Boats, and the Promise of Spring

Spring could not have come at a better time. Winters don't bring much drama here in Sarasota, Fla., but theres a chilly mood upon the land, and Ill be glad to finally be rid of it. Spring, no matter the latitude, brings with it new hope. There is nothing quite like the first breath of May in northland, when a grey fog gives way to warm sunshine, and the promise of June suddenly becomes real. I remember well spring in my former home state of Rhode Island-cherry blossoms, red-wing blackbirds, and the faint whiff of summer when we finally shook the tarp clear of our ODay Javelin, Misty. There is a reason why were alive, and spring reminds me of that. I don't pretend to know what it is, but Im sure of what its not. Its not to moan about missed chances, lament financial losses, or measure ourselves against marks set by other men. A sailor, above all others, knows that good fortune is like the wind. Todays warm westerly will be tomorrows noreaster, and we must make the best of each. I can curse the foul tide at the top of my voice, but that wont make it turn. Turn it will . . . but in its own good time.

The Search for Reliable Hands-free Onboard Communication Systems

Being able to communicate with a hands-free communication device along the length of the deck allows crew to coordinate activities like anchoring, docking, and going up the mast. Practical Sailor testers experimented with two systems: Motorola SX800R two-way radios and Nautic Devices Yapalong 3000. Both the Motorola and the Yapalong comprise a cell-phone-sized transmitter/radio unit and a separate handset. We tested them during anchoring, masthead repairs, and docking. The products were used with their mated headsets in various weather and sea conditions, including light rain and spray. The Motorola unit also was tested with a compatible Fire Fox Sportsman Throat Mic.

Rust Busters: Spray Solutions for Seized Fasteners and Other Metal Hardware

For those of us living, working, and playing on the water, rust can show up all too often, as the trailer for one of Practical Sailors test boats recently reminded us. Testers tried four aerosol products marketed as penetrating oils-WD-40, Liquid Wrench, PB Blaster, and CRC Freeze-Off-on the rusted U-bolts, and seized nuts and bolts of the neglected trailer to determine which is the best rust buster.

Mailport: 04/09

I read with interest your evaluation of first aid kits, which wrapped up with the final installment in the December 2008 issue. Id like to add a couple of points: Weekend, cruising, and bluewater sailors should invest in a good up-to-date first aid and CPR course. It is as important as a functional bilge pump. The responsible sailor can outfit a substantial and superior first-aid kit for much less money than a commercially available kit. The kit should be appropriate for the expected duration a victim will need treatment prior to evacuation. Most commercial kits contain a lot of fluff and are unnecessarily redundant-a lot of Band-Aids. I stress to distance sailors stocking a few prescription items and aggressive treatment for seasickness, beyond Bonine. I favor a solid medical text such as "A Comprehensive Guide to Marine Medicine," by Dr. Erick Weiss and Dr. Michael Jacobs, or "Medicine for Mountaineering and other Wilderness Activities," by James Wilkerson. The latter is available from Mountaineer Books. Both texts give guidance on stocking kits appropriate for your boat. Remember, the victim may be the captain or medical officer, and a novice may be the one rendering treatment. A medical guide is an invaluable resource.