Midseason Maintenance – Tip #1

Midseason Rigging Maintenance

To most of us, summer is the time for sailing. When the Florida sun sends the mercury up to the 90s, it is not a favorite time for a major boat project. Farther north, sailors may spend the winter and spring on boat projects, but the day the boat goes over the side, work is forgotten, and the fun begins. The season seems too short to squander on chores. As a rule, midseason maintenance is fairly painless. Unless you find some big problem, smaller, low-budget repairs can prevent a larger investment down the line.

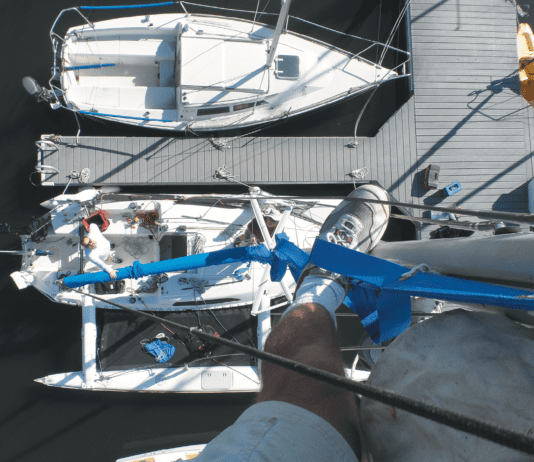

Rig

Nothing can bring a sailing season to a halt faster than losing a rig, and most rigs are lost through preventable failures of rigging components. Spending an hour on a midseason checkup should be sufficient for detecting weakened or damaged rigging or fittings.

First, check the tension of the rig at rest. Wire standing rigging continues to stretch in use, so the rig you carefully tuned in June could be quite slack by August. If you were careful in setting up the rig at the beginning of the season, and now find one piece significantly looser than the others, you may have trouble afoot. Do not just retighten the loose stay or shroud without examining it from the chainplate to the mast tang. A chainplate may be working loose; an unpinned turnbuckle may be loosening when the lee shrouds are slack; the wire may be pulling out of the swage; the mast tangs could be distorting at the clevis pin holes; or the tang bolt could be pulling down into the mast.

Check to see that all cotter pins are still in place, and that those in turnbuckles are positioned so that the turnbuckle cannot turn. Aloft, check all tang attachments, looking carefully for cracks in the mast tube or for distortion around clevis-pin holes. These checks also should be made any time the boat has gone through exceptionally heavy weather, as rigging loads increase dramatically under these conditions.

Examine spreader-end taping for worn spots or protruding seizing wire, and check the inboard ends of the spreaders for cracks and distortions. Remember, a spreader is designed to be in pure compression. Any deviation from bisecting the angle made by the shroud where it passes over the end of the spreader introduces improper loading. Spreader failure is one of the major causes of the rig going over the side.

If you have over-the-headstay roller furling, it is extremely important to check the headstay for signs of unlaying, both at the top and at the bottom. A headstay that partially unlays as the sail is rolled out or up not only gets longer, slackening the rig, but loses strength. The individual strands in 1x19 wire were pre-formed, and straightening them will quickly cause work-hardening, dramatically reducing strength.

For more tips on proactive maintenance, purchase Beth Leonard's The Voyager's Handbook, 2nd edition today!

Midseason Maintenance – Tip #2

The sailing season seems too short to squander on chores - and as a rule midseason maintenance is fairly painless. Unless you find some big problem, the summary checks and small repairs can actually prevent a larger investment of time a month or a day later.

Engine

Most sailboats have two means of propulsion: the rig and the engine. If your auxiliary is an outboard in a well, the primary midseason maintenance will be checking to see if the entire lower unit has corroded off yet. Outboards are not designed to be in salt water constantly.

If the outboard is carried on a stern bracket, routine maintenance consists of rinsing off the salt on a marine engine, checking the prop for damage, checking the starter cord for wear - these break at awkward times - and perhaps a midseason change of spark plugs. Often operated at heavy loads and with rich mixtures of oil and fuel, outboard auxiliaries tend to eat spark plugs.

On both diesel and gasoline inboards, draining water from the fuel-water separator filter is required. Unless a lot of powering is done, the engine oil should not have to be changed. An oil change every 100 hours of operation should be adequate, unless the manufacturer suggest otherwise.

The stuffing box should not leak at all when the engine is not being used, and should leak no more than a drop or so a minute with the shaft turning. If the stuffing box doesn't leak when the shaft is turning, back off a little on the locknuts, and check the operation the next time youre underway. An over-tightened stuffing box can cut the shaft.

With a relatively new engine, check the owners manual for maintenance required at specific intervals during the break-in period. It is common, for example, for cylinder head bolts to require retorquing after the first 100 hours of operation. Alternator belts may also stretch significantly when new. All belts and hoses should be closely inspected.

On a freshwater cooled engine, check the level in the coolant tank. An overheated engine can quickly be damaged.

For more tips on proactive maintenance, purchase Beth Leonard's The Voyager's Handbook, 2nd edition today!

Midseason Maintenance – Tip #3

Midseason Battery Maintenance

As a rule, midseason maintenance is fairly painless. It can be conducted on hot afternoons after a day in the office. It can be done on a lazy Sunday while the spouse and kids are off to the grandparents for an obligatory Sunday visit. Unless you find some big problem, the summary checks and small repairs can actually prevent a larger investment of time a month or a day later.

Wet-Cell Batteries

Power to crank the engine and run the lights comes from the storage batteries. If they are constantly run down and recharged at high levels, some electrolyte is bound to gas off. Charging a wet-cell battery with the top of the plates exposed will greatly reduce its life.

Don't just depend on the voltmeter on the engine panel or the electrical panel to judge the state of charge of your wet-cell batteries. Use a hydrometer, after running the engine to top up the batteries, to check for differences between individual battery cells.

Clean and grease battery cable connections, and wipe down the tops of the batteries with fresh water and paper towels after filling, charging, and cleaning. Make sure the cell caps are snugged all the way down.

For more tips on battery care and maintenance, purchase Charlie Wing's Boatowner's Illustrated Electrical Handbook today!

Midseason Maintenance – Tip #5

To most of us, summer is the time for sailing. When the Florida sun sends the mercury up to 95 degrees is not a favorite time for a major boat project. Farther north, sailors may spend the winter and spring on boat projects, but the day the boat goes over the side, work is forgotten, and the fun begins. The season seems too short to squander on chores.

However, few things can bring the fun of sailing to a screeching halt faster than a severe case of summertime neglect.

As a rule, midseason maintenance is fairly painless. It can be conducted on hot afternoons after a day in the office. It can be done on a lazy Sunday while the spouse and kids are off to the grandparents for an obligatory Sunday visit. Unless you find some big problem, the summary checks and small repairs can actually prevent a larger investment of time a month or a day later.

Below the Water

"Out of sight, out of mind" is the worst attitude you can have toward the bottom of the boat. In case you haven't figured it out yet, not all antifouling paints are created equal. Nor is the paint that works perfectly well in the Long Island Sound necessarily the right paint to use in the Puget Sound.

Many variables influence the effectiveness of bottom paints other than the amount of biocides they contain. You may not even get the same performance from the same paint on the same hull in the same location from year to year.

Despite manufacturers' claims, we have never seen a bottom paint that doesn't at least develop slime over the course of a season. Most develop much more.

Whether you have a sailboat or a power boat, occasional scrubbing of the bottom is an absolute necessity. On power boats, fuel consumption is drastically increased by a foul bottom. On sailboats, even a thin coating of slime will reduce performance.

There are simply no valid rules of thumb for how frequently a bottom should be scrubbed. The serious racing sailboat will have her bottom scrubbed weekly.

A clean bottom makes all the difference in the world in performance. Even the least competitive cruising sailboat in the water of Maine should have the bottom scrubbed once during the course of the season.

Slime and grass usually form first near the waterline. When you can see it there, it's time to go after the whole bottom. If you don't want to do it yourself, get a diver. It's money well spent.

While cleaning the bottom, don't forget the prop. If you polished the prop thoroughly with ultra-fine sand paper before the boat was launched, most marine growth can be scrubbed off with a stiff brush. Props that are idle most of the time will foul far more quickly than the prop of a power boat used everyday.

A foul prop does more than slow you down under power. It can cause overheating of the engine. Barnacles and other stubborn growth are best removed with a putty knife.

For more information on the maintenance and care of boat surfaces, purchase This Old Boat, 2nd Edition from Practical Sailor.

PS MOB – Tip #1

Sailing Harnesses: Crotch Strap Debate

There are two camps of thought regarding sailing-harness design. Based on feedback from survivors of recent sailing accidents, Practical Sailor tends to favor crotch straps for PFD-harnesses and sailing harnesses. However, crotch straps do have their downside. Many sailors find them so cumbersome that they interfere with onboard safety. Practical Sailor tester and veteran racer Skip Allan is one of these who aligns with the anti-crotch strap camp. His disdain for crotch straps, he says, is primarily due to the complexity of putting the whole thing on and adjusting it.

During our testing of a harness without a crotch strap, the harness did tend to ride up on the victim, but there was no tendency for the wearer to slip out. If the waist strap is tighter than the wearers shoulder width, its not possible for him to slip out. This insight begs the question: What about people whose tummy is wider than their shoulders? Harness waist belts should be worn as taut as is comfortable. If that practice is followed, then the wearer is unlikely to slip out.

However, survivors in three fairly recent sailing accidents that were investigated by US Sailing all indicated that they would have felt safer with crotch straps, which would have helped prevent the PFD-harness from riding up around their necks while in the water and would have helped them float better. For this reason, Practical Sailor recommends that all offshore sailors wear PFD-harnesses with crotch/thigh straps. We also recommend that the PFD-harness have a sprayhood and that wearers know how to deploy and use it.

Ultimately, it is imperative to test your safety gear in the water to see how comfortable you are with or without crotch straps, and whether you can live with the inconvenience when working on deck.

For more advice and recommendations on the best ways to stay aboard in all conditions, purchase and download MOB Prevention & Recovery today!

PS MOB – Tip #2

Whether made of wire, rope, or webbing, a good jackline system provides a secure, convenient, and continuous means of attachment for safety harness tethers while crew members are on deck. As your life may depend on a jackline keeping you aboard, it should be made of strong and lowstretch material, be kept as taut as possible, and be routed inside the shrouds down both sides of the deck as close to the centerline as possible.

Ideally, jacklines would be located to allow a harnessed and tethered crew to reach the rail, but not beyond. Once a crew goes over the lifelines and into the water, recovery becomes vastly more difficult. It is always good practice to clip onto the windward side jackline to minimize the chances of going over the side.

Because jacklines attract dirt and grime, are subject to UV degradation, abrasion, and chafe, and can provide a potential ankle-spraining hazard, offshore cruisers and racers wisely remove their jackline systems when not in use.

Jacklines can be secured to the boat at most strong and through-bolted attachment points such as the stem head fitting, mooring cleats, windlass, U-bolts, and padeyes. Using lifelines as jacklines is not recommended due to the necessity of frequent clipping and unclipping of the tether hook while passing stanchions. Lifelines used as jacklines are also too close to the rail of the boat for safety. In the event of crew being launched overboard by an off-balance fall or breaking wave, a tether clipped to a lifeline would likely break off the stanchion, uproot the stanchion base, or otherwise damage the lifeline system, making man-overboard recovery even more difficult.

An excellent method to terminate the aft end of a jackline is to lash it to a padeye. Lashing allows adjustment and tensioning of the jackline, as well as easy removal. A valid argument can be made that jacklines should end 6 to 8 feet forward of the stern so a man-overboard cannot be dragged and drowned behind the boat.

For more advice and recommendations on the best ways to stay aboard in all conditions, purchase and download MOB Prevention & Recovery today!

PS MOB – Tip #3

The primary purpose of the safety harness tether, the vital link between you and the boat, is to keep the wearer aboard, not dragging alongside or hydroplaning astern.

After extensive on-the-water evaluations, Practical Sailor has crafted a list of criteria for the ideal tether. It should incorporate a quick-release snap shackle at the inboard end with a lanyard long enough so that the wearer can easily release the snap shackle under load. The tether should be just long enough for the wearer to reach the rail should he fall overboard. PS found 6 feet to be the longest practical tether length. The boat end of the tether should have a non-magnetic, locking snap hook that can be opened with one hand.

Tethers with elastic, allowing them to contract when not under load, are preferable. The ability of tethers with integrated elastic to retract helps keep the tether out from underfoot and free of entanglements with winch handles, engine controls, and deck gear. It is also easier to comfortably wrap these elastic tethers around your waist or over your shoulder when theyre not in use.

A quick-release snap shackle at the harness end of a tether is especially important in case the wearer becomes trapped under an inverted boat or in a tight spot, like on the wrong side of a jib sheet. The quick-release shackle at the harness end has the added benefit of allowing the wearer to go below before unhooking, leaving the tether clipped on deck and dangling down the companionway or hatch, to be easily reconnected before the sailor returns topside. Quick-release shackle lanyards should never have loops, which could inadvertently snag and open the shackle.

For additional details on what Practical Sailor looks for in safety tethers and other advice and recommendations on the best ways to stay aboard in all conditions, purchase and download MOB Prevention & Recovery today!

Mounting Hardware – Tip #1

A Better Way to Mount Deck Hardware

Improperly mounted stanchion and pulpit bases are a major cause of gelcoat cracks in the deck radiating from the attached hardware. The cracks are usually the result of unequally stressed mounting fastenings or inadequate underdeck distribution of hardware loads. Frequently, a boat is received from the builder with local cracks already developed. Once the deck gets dirty enough, these minute cracks start to show up as tiny spider webs slightly darker than the surrounding deck gelcoat While repairing these cracks is a fairly difficult cosmetic fix, the underlying problem - poor mounting - is fairly easy to correct in most cases.

For better or worse, production keep the cost of their boats competitive. Unfortunately, cutting corners is the rule rather than the exception in production boatbuilding. While you can't change that situation, you can do a lot to correct the shortcomings that are a function of corner- cutting, including poorly mounted stanchions and pulpits.

The most typical problem in stanchion mounting is the base which straddles the inward-turning flange of the hull-to-deck joint. Frequently, the outboard bolts will go through both the hull and deck, while the inboard fastenings merely go through the deck. When a backing plate is installed that straddles the edge of the inward-turning hull flange under the deck, it is frequently distorted as the bolts fastening the stanchion bases are tightened. Tightening down the bolts when the backing plate doesn't lie flush to the underside of the deck inevitably causes local stresses in the deck, frequently resulting in the characteristic spider web of gelcoat cracks.

In order to avoid the problem, some builders simply use oversize washers under the nuts of through-deck bolts. These are not adequate to resist strong local loads, such as leaning hard against a lifeline stanchion. A backing plate of rigid material, at least the size of the base of the hardware to be attached, is the proper solution.

It is fairly common for builders to use fiberglass backing plates, cut from discarded sections of moldings such as cutouts for hatches. While a fiberglass backing plate is better than nothing, it can easily split or distort when bolts are tightened, reducing its effectiveness.

With stainless steel or aluminum hardware, fastened with stainless steel bolts, backing plates of stainless steel or aluminum, between 1/4-inch and 1/2-inch thick are a good choice. Marine-grade plywood, if it is sealed properly, also makes a good backing plate, although you will want to seal it with epoxy to prevent rot. One of our favorite backing plates is G-10, a superstrong - but not cheap - fiberglass laminate especially made for use in highly loaded areas.

For more advice and information on the installation of backing plates for more solid mounting of deck hardware, purchase This Old Boat, 2nd Edition from Practical Sailor.

Offshore Cruising – Tip #1

Offshore Cruising

We are frequently asked how much it costs to go cruising. The answer is that it costs whatever you're willing to spend.

It's fair to say that if you eat out five times a week ashore in the US, or bring home pizza or Chinese daily, you're not going to become a self-sufficient and imaginative chef the minute you go cruising. Likewise, if your home ashore looks like it was just struck by a hurricane, your boat is likely to take on the same aspect. For the average middle-class, middle-aged couple used to a moderate level of comfort, the cost of cruising will be not that much different from the cost of life ashore.

Some aspects of long-range cruising are cheaper than life ashore, some are more costly. Boat insurance for doublehanded offshore cruising costs about 50% more than similar coverage for coastal sailing. Hauling out might at first seem cheaper in a foreign port, but flying a new set of fuel injectors and an injection pump into Panama may set you back the full difference and then some.

Marina space is almost always cheaper once you leave US waters. Two nights in an expensive Ft. Lauderdale marina can cost more than a week in Singapore's upscale Raffles Marina. (Raffles featured air-conditioned marble bathrooms and fitness center, a nice swimming pool, and a free fancy Chinese dinner weekly for cruisers.)

And the list goes on and on. Can you do without some of the stuff on your list? Sure. Even so, it's probably going to cost more than you think it will.

For more tips and details on cruising offshore, purchase Beth Leonards book The Voyagers Handbook today!

Offshore Cruising – Tip #2

Offshore Cruising

Perhaps the biggest surprise during a circumnavigation is just how critical the engine is to a cruising sailboat. Running under power for almost 25 percent of the miles that passed under your keel is not unusual. The engine also provides battery charging for everything from lighting to making fresh water. It drives the refrigeration system, and makes hot water.

This percentage of time under power is not unusual. There are parts of the world where motoring is the norm, if you want to get anywhere in a rational amount of time. The South China Sea and Java Sea, for example, have notoriously light and fickle winds, as do other parts of Southeast Asia. Headed north in the upper half of the Red Sea, your two options are usually to beat into 35-knot headwinds, or wait for calm periods and motor. The same goes for parts of the Mediterranean.

When we began loading and unloading for a voyage, the sheer volume of parts and service items for the engine and its associated systems are pretty indicative of how much you count on it.

Engine spares are among the heaviest, space-consuming, and expensive items you will carry on your boat. It's true that you can get basic engine consumables in all but the most remote parts of the world. It's also true that relying on local sources of supply in out-of-the-way places can add an enormous amount of stress to your cruising.

Even in areas of the world where engine spares are readily available-Singapore or Australia, for example-it may be a logistical nightmare to try to get to the local source of supply, or they may not have what you need in stock at that particular moment. In countries with language and cultural barriers to easy communication, finding parts may be frustrating or impossible. If it's not in stock, you can't count on getting it in a rational timeframe. The bottom line is simple: carry it with you.

For more tips and details on cruising offshore, purchase Beth Leonards book The Voyagers Handbook today!