Heating Systems – Tip #3

Have you ever stopped and thought about how many boat heating options there are? It can be over-whelming even for the most experienced technical mechanic. And yes, there are a multitude of ways to extend the season and keep a cozy cabin, ranging from simple to complex. But how do choose the best heating option? You must consider many factors, when making this decision.

A definite correlation exists between the degree to which we are warm and dry, and the enjoyment of a sail, or a night at anchor. A damp and chilly environment may be exacerbated by a poorly insulated hull, leaks, and condensation. Sitting beneath a drippy port or headliner, or curling up in a damp bunk can make or break your sailing experience.

Your boat can be matched to a heating system that, at one end of the spectrum, will simply prevent the formation of icicles or, at the other, provide a space as warm as that den at home. Sources range from electric "cubes" and oil-filled radiators plugged in dockside, to hanging lamps, to the nautical equivalent of central heating. Cost ranges from almost nothing to the limits of your credit card.

How to determine how much heat you need? One method is to determine the average of the water and outdoor temperatures during the coldest months. Then, assume that 700 cubic feet of interior volume requires 3,000 Btu to maintain a temperature 25 higher than that average. However, there really are too many variables involved to put much stock in a formula like that. Boats, people, and locales all differ far too much, and what's comfortable enough for one person will be misery for another.

In order to get truly adjustable comfort, or to equip a boat to stand up against temperature extremes, a fixed system will be required. We could then divide those systems into two subsets-ones that carry heat around the boat by means of pipes or ducting, and those with a strong central heat source and fans to move the air into the far reaches of the boat.

Nothing is more efficient than radiant heat produced by the sun, or a heat source that directly affects the area to which it is exposed. However, while sitting in direct sunlight on a cold or damp deck, your nose may be toasty while moss grows on your posterior.

The same is true belowdecks. Few boats are well-insulated, and whatever warmth is developed below on a cold night tends to be exchanged at a fast rate for the chilly stuff.

Here's a scenario that will be familiar to many: The air temperature in the harbor is 40 F. and there's a wet wind blowing at 12 knots. The water temperature is 46 F. You're sitting in the main cabin right next to your main heat source (a wood stove, an electric radiator, whatever). Your head and torso are hot. Your hands are warm. Your feet are cold. The forepeak is cold. The aft cabin is cold. The head is cold. You lean outboard and put your feet up. Within a minute, your head is cold and your feet are hot.

You may have an excellent source of heat and a lot of Btus, but this is what life will generally be like in cold weather if you have no method to circulate warm air into occupied spaces efficiently. Options include units mounted on bulkheads that rely on fans; ducted systems with outlets in living and sleeping quarters; and heat produced by the circulation of warm fluids to a heat exchanger.

Whether you are just considering upgrading your heating system or you ready to start the project, start your research and sharpen you technical know-how by reading Nigel Calders comprehensive guide on how to maintain, and improve your boats essential systems. If its on a boat and it has screws, wires or moving parts, its covered in the Boatowners Mechanical and Electrical Manual. When you dock or leave the deck with this book, you have at your fingertips the best and most comprehensive advice on technical reference and troubleshooting all aspects of your boat gear.

Keel maintenance – Tip #1

Often seemingly minor problems on boats are indicators of more serious problems that, if not addressed early, will lead to bigger headaches and more expensive repairs. Gelcoat cracking on the deck, which can be either a harmless cosmetic problem or a symptom of wet core or some other structural failure, is a classic example of this scenario.

Your keel seam falls into the same category. It might easily be resolved with some underwater sealant, or it could be a symptom of a far more serious problem. Without dropping and inspecting the keel, you cannot know for sure. Given that this iron keel is 28 years old, the likelihood of serious corrosion between the stub and the ballast is significant. The keel bolts themselves may also be corroded. If your keel has never been dropped and inspected before, a close inspection is long overdue, particularly if you plan to take the boat offshore or beyond coastal waters.

Even if all is well with your keel assembly, it is unlikely that you will permanently seal your keel seam without some thorough prep work at the joint. Certainly, you may be able to fill the seam with a good adhesive sealant like you did before, but it will likely open again over time and you will not solve any larger hidden problems.

Once your inspection and any repairs are taken care of, achieving a proper seal will ensure this problem doesn't crop up again. To get a good seal, both the keel stub and ballast must fit cleanly together. In other words, the mating surfaces should be uniform and flush. Typically, the joint would require a minimum of sealant, most of which squeezes out of the joint upon tightening the keel bolts. If there was a poor fit to start with, more sealant isn't the answer.

The ballast needs to be removed, the surfaces cleaned, and a high-density epoxy filler will be required to fill the voids.

Once your keel stub is relatively smooth and free of voids, you can use it to "mold" a clean mating surface in the keel. To do this, you need a sheet of heavy polyethylene plastic that will fit like a gasket between the keel stub and keel and keep the two from bonding. For extra protection, you should cover both sides of the "gasket" in a mold release wax, or similar mold release agent. You must also make sure the keel bolts are liberally coated and packed in grease. A failure to ensure a clean release here can cause some significant problems. You then fill the voids in the mating surface of the ballast keel with putty or high-density Chockfast (www.chockfast.com). The hull and its plastic gasket is then lowered back onto the epoxy-filled ballast (with the plastic in between the hull and putty-coated keel), and the excess epoxy squeezes out evenly, developing a flush fit. Any excess epoxy should be cleaned away with a putty knife or plastic spreader. Once the epoxy has cured, the hull is again lifted, and the epoxy and grease residue are thoroughly cleaned. Finally, the hull/ballast joint is bedded with a polysulfide or polyurethane adhesive meant for underwater service. The parts are mated and lightly bolted up. Dont make the final torque adjustments until the sealant has fully cured.

For more advice on how to inspect and repair your boat and boats keel, purchase This Old Boat, 2nd Edition from Practical Sailor today!

Life Raft – Tip #1

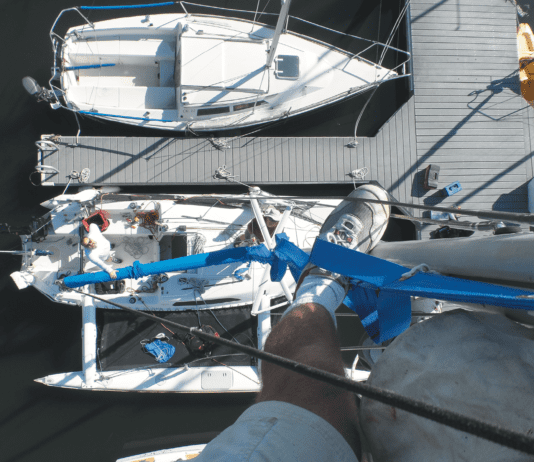

Life raft location is a challenging question to answer. A strong, fit person may be able to heft and heave a life raft of about 100 pounds. However, darkness or a slippery, submerged deck can significantly complicate the issue. You want to place the life raft where it will not be prematurely launched by a boarding sea and yet can be slid over the side. On a small sailboat, that location can be hard to find.

All too often, the best spot is high on a coach roof, and the brackets are bolted through a deck that was never intended to carry the shear loads that a breaking wave could exert on such an installation. In a worst-case scenario, the life raft and mounting bracket rip away, leaving a hole in the cabin top. Be sure that the mounting point is structurally sound enough to handle the loads imposed by breaking seas. Some makers show their life rafts clamped to a stern pulpit, a structure not intended to take these loads.

For more information on how to select the right life raft, puchase and download Practical Sailor's ebook, Survival at Sea, Volume 1: Life Rafts today!

To read more about how to best prepare for an emergency on the water, purchase the entire Survival at Sea ebook series from Practical Sailor. Four volumes in all - Life Rafts, Ditch Bags, Onboard Medical Kits, and Survival Electronics. Buy all four for the price of three!

You'll get one complete ebook FREE.

Life Raft – Tip #2

Once the life raft is launched and inflated, it can be brought alongside a sinking vessel for the crew to transfer directly into the life raft without jumping into the sea.

At this point, the larger the opening, the better. However, once everyone is in the life raft, the optimum opening size changes. If the abandon-ship situation includes fire or rapid sinking, it may become necessary to enter the water before entering the life raft, and the best method is to jump in close to where the painter can be grabbed and work your way to the life raft rather than attempting to swim to it.

Clothing and a PFD can make climbing into a life raft cumbersome.

Crew weakened by cold water and encumbered by the stress of a survival situation are often exhausted when it comes time to get into a life raft. Our professional yacht captain/ex-naval officer and in-the-water evaluator, Eric Naranjo, ranked boarding aids as the most important safety feature on a life raft: A life raft doesn't do you any good if you can't get in it, he said.

For more information on how to select the right life raft, puchase and download Practical Sailor's ebook, Survival at Sea, Volume 1: Life Rafts today!

To read more about how to best prepare for an emergency on the water, purchase the entire Survival at Sea ebook series from Practical Sailor. Four volumes in all - Life Rafts, Ditch Bags, Onboard Medical Kits, and Survival Electronics. Buy all four for the price of three!

You'll get one complete ebook FREE.

Life Raft – Tip #3

A good life raft not only prolongs your ability to survive, but also adds to your chance of being rescued. Despite the fact that some rafts can be trimmed up by retractable water ballast bags and actually sailed downwind at a knot or two, the real hope for rescue lies in being visible to others.

In a passive sense, this may mean a ships crew seeing your yellow, orange, or red canopy, or a spotlight hitting the reflective tape of the canopy at night. Signaling mirrors, flares, water-surface streamers, VHF radios (marine and aviation), EPIRB (emergency indicating radio beacons), (personal locator beacons), SART (search and rescue transponders), cell, and sat phones all play a role in being visible.

For more information on how to select the right life raft, puchase and download Practical Sailor's ebook, Survival at Sea, Volume 1: Life Rafts today!

To read more about how to best prepare for an emergency on the water, purchase the entire Survival at Sea ebook series from Practical Sailor. Four volumes in all - Life Rafts, Ditch Bags, Onboard Medical Kits, and Survival Electronics. Buy all four for the price of three!

You'll get one complete ebook FREE.

Life Raft – Tip #4

Fundamental to the integrity of any life raft is the material with which it is constructed and the quality of construction, so it is not surprising that the new ISO 9560 standard addresses material tear-test and breaking strength. These same material specs are adopted by the new ISAF standard.

Modern inflatable life rafts are made of tough nylon fabrics that have been coated or "calendared" with natural or synthetic rubber to make them air tight. The tear strength of the material and seams are engineered to withstand impact loads associated with breaking seas and abrasion from curious sea creatures. The trade-off between weight and rugged reliability is a tough balancing act and good engineering is essential.

For more information on how to select the right life raft, puchase and download Practical Sailor's ebook, Survival at Sea, Volume 1: Life Rafts today!

To read more about how to best prepare for an emergency on the water, purchase the entire Survival at Sea ebook series from Practical Sailor. Four volumes in all - Life Rafts, Ditch Bags, Onboard Medical Kits, and Survival Electronics. Buy all four for the price of three!

You'll get one complete ebook FREE.

Lightning Protection – Tip #1

Getting the Charge out of Lightning

Most boat owners have only the vaguest idea of what is involved in protecting their boats from lightning damage. Many believe that their boats are already protected by the boat's grounding system. Most are wrong.

Just because your boat may be bonded with heavy copper conductors connecting the masses of metal in the boat doesn't mean that it is protected against lightning. A bonding system may be a part of a lightning protection system, but bonding itself offers no protection to the boat unless a good, direct path to ground is part of the system.

The purpose of bonding is to tie underwater metal masses in the boat together to reduce the possibility of galvanic corrosion caused by dissimilar metals immersed in an electrolyte. The purpose of lightning grounding is to get the massive electrical charge of a lightning strike through the boat to ground with the least possible amount of resistance.

Most lightning never reaches the earth: it is dispersed between clouds of different electrical potential. The lightning that concerns sailors is the discharge of electricity between a cloud and the surface of the earth, or an object on the surface of the earth, namely, your boat. The amount of electricity involved in lightning can be, well, astronomical. We're talking about millions of volts.

Granted, the duration of a lightning strike is extremely short. But in the fraction of a second it takes for lightning to pass through your boat to ground, a great deal of damage can be done. And here's the kicker. No matter how elaborate your lightning protection system, there is no guarantee that a lightning strike will not damage your boat.

Certainly you can reduce the potential damage from a lightning strike. That's what protection is all about. But to think you can eliminate the possibility of damage is folly. There are too many recorded instances of so-called properly lightning-protected boats suffering damage to believe in the infallibility of lightning protection systems.

For more information on how to best protect your boat from lightning strikes, purchase Nigel Calder's "Boatowner's Mechanical & Electrical Manual" from Practical Sailor.

Lightning Protection – Tip #2

Most boat owners have only the vaguest idea of what is involved in protecting their boats from lightning damage. Many believe that their boats are already protected by the boats grounding system. Most are wrong.

Just because your boat may be bonded with heavy copper conductors connecting the masses of metal in the boat doesn't mean that it is protected against lightning. A bonding system may be a part of a lightning protection system, but bonding itself offers no protection to the boat unless a good, direct path to ground is part of the system.

While neither aluminum nor stainless steel is an outstanding electrical conductor, the large cross-sectional area of both the mast and the rigging provide adequate conductivity for lightning protection. The trick, however, is getting the electricity from the mast and rigging to the water.

The straighter the path is from conductor (mast and rigging) to ground, the less likely are potentially dangerous side flashes. Put simply, side flashes are miniature lightning bolts which leap from the surface of the conductor to adjacent metal masses due to the difference in electrical potential between the charged conductor and the near by mass of metal. Ideally, therefore, the path from the bottom of the mast and rigging to ground would be absolutely vertical. In practice, this is rarely achieved.

If the boat has an external metal keel, the mast and standing rigging is frequently grounded to a keelbolt. There are pitfalls to this method. First, the connection between the bottom of the mast and rigging to the keelbolt must be highly conductive. ABYC (American Boat and Yacht Council) standard TE-4 for lightning protection systems require that these secondary conductors have a conductivity at least equal to that of AWG #6 copper-strand cable. There is no drawback to using an even larger conductor.

Connecting the short conductor to the mast and keelbolt presents some problems. A crimp eye can be used on the end that is to be attached to the mast, but you may have to fabricate a larger eye for attachment to the keelbolt. This can be made from sheet copper. Soldering the connections is not recommended, since the heat generated in a lightning strike could melt the solder.

Then you have to face up to a basic problem. Your mast is aluminum, yet youre connecting it to ground with a copper cable. Everyone knows that aluminum and copper are not galvanically compatible, so whats the solution? While it will not eliminate corrosion, a stainless steel washer placed between the copper cables end fitting and the aluminum mast will at least retard it. But this connection is going to require yearly examination to make sure that a hole isn't being eaten through the mast. In addition, of course, the process of corrosion creates wonderful aluminum oxide byproducts, which have very low conductivity. The aluminum oxide may reduce conductivity to the point where your theoretical attachment to ground is in fact non-existent. Once again, disassembling the connection and cleaning it yearly are essential to maintain conductivity. Constant attention to all the conductor connections is essential in any grounding system, whether its for lightning protection or grounding of the electrical system.

For more information on how to best protect your boat from lightning strikes, purchase Nigel Calder's "Boatowner's Mechanical & Electrical Manual" from Practical Sailor.

Magnetic Field – Tip #1

Unsettling to contemplate, the flow of electrons that constitutes electric current also creates a magnetic field. An onboard magnetic field that is strong enough may deflect your compass and cause deviation. DC circuits are the primary culprit; AC circuits are comparatively insignificant. The strength of the field is proportional to current flow; 8 amps produce twice the deflection of 4. Twisting the leads before installing wire so that positive and negative produce opposing fields has been the traditional defense. Leading separate positive and negative wires from the same circuit on opposite sides of the binnacle only doubles the error. The better you isolate your compass from electric circuits, the less the force will be with you.

For more than 1,000 tips, suggestions, evaluations, and nuggets of hard-won advice from more than 300 seasoned veterans, purchase "Sailors' Secrets: Advice from the Masters" from Practical Sailor.

Marine Toilets – Tip #1

Once considered a frivolous luxury for larger sail boats and motoryachts, the new breed of electric heads are generally more compact, more reliable, and less expensive than their predecessors.

Manufacturers are offering multiplying models and options for both the marine and RV markets. For boats currently fitted with manual heads, an upgrade is not beyond the capabilities of a competent do-it-yourselfer.

Electric toilets have another advantage: the automatic electric macerating pumps do a better job of efficiently eliminating waste, especially for the landlubbers and guests who don't know whether they should pump once, twice, or sixteen times.

Any toilet upgrade must take into account plumbing details, but a conversion to electric also entails additional power requirements, wiring details, and over-current protection. Operating for only a few seconds per flush, the electric-pump toilets reviewed here, will not add a great deal to the daily amp-hour loads of a cruising boat. However, the momentary loads of electric pump and macerators can be as high as 30 amps, a demand-surge that can have consequences if the house battery bank is low or the electrical system is not designed to accept such loads. There is more than a grain of truth to the sea yarn about the autopilot that took a sharp turn to port every time someone flushed the toilet.

When installing a new toilet, follow the instructions carefully as to wire size and discharge sanitation hose size and length. Most boats will have a inch through-hull seacock valve as the inlet for raw-water flushing. For the outlet, a 1 outflow hose will usually lead to a lockable Y-valve that diverts flow to either a holding tank or directly overboard through a seacock. (The Y-valve must be locked or sealed in sensitive areas designated as No-discharge Zones.)

There are dozens of electric toilets of different models depending on size, weight, style, voltage, color, function and features. Several models are available in different iterations. They can come with or without separate inlet water pumps, macerator pumps, solenoids, or electronic control boxes. Some come with a simple push-button or a more elaborate multi-functions remote-control panel, with separate buttons for filling and flushing. Some are Spartan compacts; others are very stylish household types. Prices range from $429-$9,999.

For advice on choosing the best marine toilet for your boat, purchase and download Marine Sanitation Systems, Volume 1 - Marine Toilets today!