Winterizing an inboard engine installation means a lot more than filling the cooling system with antifreeze and stuffing a rag in the exhaust outlet. It means taking care of the exhaust system, the fuel system, the engine controls, and other components of the drive train, such as the shaft and prop. If you want to do these things yourself — none of them is difficult, only time consuming — plan on a long day of work, or perhaps a leisurely weekend.

288

It’s work that will pay off, however, both in improved understanding of your boat’s propulsion system, and in money saved. At $25 per hour, the simple projects described here will save you about $200. Few special tools are required, and the only skill necessary is a modicum of common sense.

While many items of drive train maintenance can be done as easily in the spring as in the fall, the rush to get the boat back in commission frequently means that some items fall to the bottom of the priority list, and may never get done. Most sailors sadly neglect their boat’s mechanical components, sometimes with somewhat self-righteous claims that sailors don’t really need to know such stuff. Invariably, these are the folks whose auxiliaries die with less than a thousand hours on them, and whose gearboxes and shift linkages fail when they’re docking (When do you think your shift linkage is going to seize — when you’re traveling ahead in a straight line at six knots?)

Fuel System

The first component of the drive system to be attended to is the fuel system. Whether you have a diesel engine or a gas engine, a fuel additive can be used to stabilize the fuel during the storage period, even if it is only a month or so.

Diesel and gasoline stabilizers are not interchangeable. Diesel additives usually have biocides to prevent the growth of system-clogging organisms in the fuel.

As obvious as it may sound, read the instructions before buying a fuel stabilizer. Some require draining the tank before treatment, others require adding fuel to the tank after treatment, and some can just be dumped into a full tank.

In any case, it is important to run the engine for 10 minutes or so after treating the fuel, so that the additive gets into the fuel lines and filters, the carburetor of a gas engine, or the injectors of a diesel engine.

If the boat is already on land when you go through the winterizing process, run a water hose to the raw water intake to provide engine cooling water. Most engine intakes are smaller than the plastic or metal end fitting on the hose. A 6′ length of hose with a female fitting can simply be screwed onto the mainwater hose, and the end of the short hose (with no fitting) jammed into the raw water intake. Someone should keep an eye on the hose while the engine is running just to make sure it doesn’t pop out.

288

Fuel filters can also be changed at this time. A strainer-type gasoline filter should be cleaned — out of doors — with fresh gasoline to remove sediment, and the bowl of the filter should be drained.

Likewise, it is important to drain the water from a diesel separator, particularly on a boat laid up in a cold climate. Filter elements can be changed at this time.

If filters and separators are taken care of before treating fuel, they will become filled with stabilized fuel when the engine is run.

There are two schools of thought about storing fuel in the tanks when the boat is laid up. In the past, with gasoline systems using copper tanks and copper fuel lines, the practice was usually to drain the system for the winter to prevent the formation of gum. With modern gasoline and stabilizers, this problem is minimized, and the tanks will fare well if left full.

Opinion about the condition of diesel tanks during varies. It is true that during suspended sediment in diesel fuel will settle out on the bottom of the tank. This sediment could perhaps be a problem next season, if you were sailing in very rough conditions with very little fuel in the tank. The sediment could be stirred up, resulting in badly contaminated fuel. That, of course, is why you should have two filters in your diesel fuel system.

At the same time, an empty or almost empty metal fuel tank in a boat laid up in a cold climate can generate a lot of condensation. If you have a black iron diesel fuel tank, the condensation can accelerate corrosion. The safest course is to keep the fuel tank full on any boat having metal tanks.

Fiberglass tanks present another set of problems. Although the typical orthophthalic resin used in building is highly resistant to chemicals, it is not perfectly resistant. Isophthalic resins offer considerably more resistance to attack by chemicals, and are therefore preferable for use in fuel tanks. Unfortunately, relatively few builders use isophthalic resins because of the additional cost. If you have fiberglass fuel tanks, and are unsure of the resin used in their construction, it would be prudent to lay up the boat with the tanks empty.

Engine

With the engine still warm from running treated fuel through the system, change the crankcase oil. Unless your engine has a built-in crankcase pump, you’ll have to pump the oil out through the dipstick hole.

You can either use a manual pump such as the Par Handy Boy, or any one of a number of small impeller pumps designed to fit in the chuck of a 1/4” drill. The drill-driven pumps are quicker, and are frequently easier to use in the crowded engine compartment. However, some of them use a rubber impeller which is not designed to run dry, so that they can have a short life if the pump doesn’t prime quickly.

After draining the oil, change the oil filter element if the engine is equipped with a spin-on filter. Fill the engine with fresh oil.

288

It is particularly important to change the oil when laying up a diesel engine. Most diesel fuel contains sulfur in varying amounts. A byproduct of the combustion of diesel fuel which contains sulfur is sulfuric acid, which over time will do distressing things to the inside of your engine.

If your transmission is lubricated separately from the engine, check the fluid level. Plan on changing transmission fluid every other year, at least, or once a year on a boat whose engine gets more than about 50 hours of use per year. It’s impossible to change engine oil and transmission fluid too frequently.

The engine’s cooling system must also be winterized. With a fresh water cooled engine, check the fluid level in the coolant tank, topping up with a 50-50 mixture of water and antifreeze if necessary.

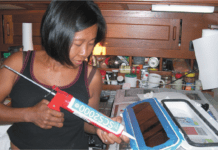

The next step is basically the same for both raw water and fresh water cooled engines. The raw cooling water must be replaced with a 50-50 mix of water and antifreeze. The method varies depending on whether the engine is decommissioned while the boat is in the water, or after it has been hauled.

If the boat is still in the water, shut off the raw water intake and remove the hose from the intake seacock tailpiece. Fill a clean bucket with a 50-50 antifreeze mixture. Dip the water inlet hose into the bucket of antifreeze.

Now a little coordination is required. You want to start the engine and run it long enough to make sure that the antifreeze mixture has filled the cooling system, including the muffler. You’ll know you’ve done this when the cooling water ejected through the exhaust is the color of your antifreeze mixture.

At the same time, you don’t want to run the engine after you’ve sucked up the entire bucket of antifreeze. You want the raw water system to be full of antifreeze, not empty. It will take two people: one to hold the hose in the bucket, and one to operate the engine and watch the exhaust. Obviously, a positive means of communication between the two persons involved is also required. Your voice may not travel to the helm from belowdecks (“Shut off the engine.” “What?” “Shut off the engine!” “I can’t hear you.” “SHUT OFF THE DAMN ENGINE!“), but it’s guaranteed to travel across the boatyard.

If the engine is laid up with the boat ashore, you can feed the antifreeze mixture directly through the raw water intake on the outside of the hull using the hose you made up for running the engine prior to changing the oil.

Don’t try to save time by running the engine only once to circulate treated fuel, heat up the oil for changing, and suck up antifreeze. You probably need about 10 minutes of engine running for winterizing the fuel system and warming up the oil. Sucking up antifreeze will probably take a minute or less. At about $5 per gallon, you don’t want to waste too much antifreeze.

A gallon of antifreeze -two gallons of 50-50 mix should handle engines up to about 40 horsepower. Then add extra for hoses. The length of run of the raw water discharge hose to the muffler is as much a determinant of the amount of antifreeze used as is the size of the engine.

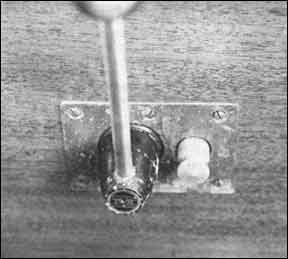

When you shut down the engine after winterizing, remove the ignition key and spray the inside of the switch with a lubricant like WD-40 or CRC.

Exhaust System

If you have pumped enough antifreeze through your engine so that the discharged cooling water looks exactly like the antifreeze mixture in the bucket, your waterlift muffler should be well protected. If you want to be supercautious, install a drain plug in the muffler and drain it when laying up the engine. Reinstall the plug immediately after draining so you don’t have to worry about it in the spring. The same goes for any other drain plugs in your system that you remove. Reinstall them now, not later.

288

Shaft and Prop

Haulout time is the proper time to check the condition of the prop, shaft, cutless bearing, and stuffing box. On a boat that is laid up ashore for the winter months, you can save yourself a fair amount of effort in the spring by doing these tasks when your other drive system layup is done.

First, check the prop for damage and corrosion. Pitting of the blades or discoloration may indicate an electrolysis problem which should be tracked down over the winter.

Wiggle the prop shaft in the cutless bearing. There should be no slop, only the yielding of the rubber against the metal shaft. If the rubber bearing is worn, get a replacement now, rather than waiting until spring. Cutless bearing replacement has the nasty habit of becoming a real project, as the bearing shell frequently seizes in the strut, and must be sawn out or punched out.

This is also a good time to check the shaft for wear. Disconnect the shaft flange at the transmission, and pull the shaft out far enough to see the surface of the shaft where it normally sits in the stuffing box and cutless bearing. A shaft which is worn at the stuffing box may be very hard to seal. Tightening the stuffing box to overcome leaking around a worn shaft will only aggravate the problem. Winter is the time to deal with these projects, rather than the spring, when your primary concern is getting the boat back in commission.

If you have a folding prop, check the blades for slop at the pivot pin. Unless the pin fit is tight, wear will increase, not only in the prop blades but at the cutless bearing and stuffing box. A machine shop can bush the hole in the blades for the pivot pin, restoring a tight fit, and you can easily replace the pin if necessary. If you try to get this done in the spring, you’ll find everyone too busy to help you.

Don’t try to check engine and shaft alignment with the boat out of the water. This is particularly true with a flat bottom, fin keel boat. The weight of the hull on the keel can easily affect engine alignment.

In fact, if you have a fin keel boat with the engine sitting in the middle of the boat, it would be prudent to disconnect the shaft before the boat is hauled, to minimize the possibility of damage.

Engine Controls

On a boat used in salt water, there’s a good chance that the shift and throttle controls have ingested a fair amount of salt over the course of the season. You may want to disassemble the control levers, clean them with fresh water, and give them a dose of spray lubricant.

This is particularly true with controls using pot metal or aluminum components. A surprising number of engine controls use galvanically incompatible materials -notably pot metal castings -which turn to powder in a few years of use in salt water if cleaning and lubricating are not done religiously.

On controls mounted in the cockpit well, check the back side of the mechanism to make sure that it is still well greased.

Conclusion

It takes a fair amount of discipline to tackle the jobs associated with laying up an engine system, particularly when your primary interest is putting the boat away for a while, not fussing with it. However, this is true preventive maintenance, and it will pay off with reduced replacement and maintenance costs, as well as more reliable operation of the drive system.

Laying up your engine will give you more practical knowledge about the operation of things mechanical than a lifetime of just turning the key and pushing the levers. Doing it yourself can help you spot potential trouble before it interrupts your sailing season. The first step toward making your boat a better boat is learning what makes it tick, and the best way to learn that is to roll up your sleeves and get busy.

-NN