In the early 1970s, when the fiberglass sailboat revolution was in full swing, so were the so-called swing keels. Three years after Richard Nixon was elected president, partly on the promise of ending the Vietnam War, U.S. planes still were bombing Cambodia, hippies and peaceniks were marching and both were flashing the V sign. In 1971 Sylvia Plath published “The Bell Jar,” Louis Armstrong died, the crews of Apollo 14 and 15 landed on the moon, cigarette advertisements were banned from television, and Joe Frazier outpointed Muhammad Ali to retain his world heavyweight boxing title.

On the domestic level, Americans were taking their leisure time more seriously than ever, taking to the highways in RVs and to the waterways in all sorts of new fiberglass boats. Magazines devoted exclusively to sailing began to appear. One of the most popular type of boats was the “trailersailer,” relatively light-displacement sloops with centerboards and swing keels, that could be stored in the backyard or driveway, towed behind the family station wagon and launched in about 45 minutes. Trailer-sailers promised yacht-style accommodations at an affordable price-in terms of both initial investment and annual upkeep.

Trailer-sailers never really disappeared from the sailing scene, but they haven’t been exactly an exploding market force either. But becuase we see indications that trailer-sailers are showing signs of increased interest from boat buyers, we thought we’d take a look at four early-and mid-19702 designs.

The Ballast Problem

For stability, a sailboat must have an underwater appendage such as a keel or centerboard, and ballast. Both are at odds with the concept of an easily trailerable boat that can be launched at most ramps. A deep fixed keel is untenable. One solution is to design a long, shallow keel, as seen on many Com-Pac boats, and older models such as the O’Day22. Unfortunately, windward performance suffers because there is little leading edge and foil shape to provide lift.

During the last few years, several builders have experimented with water ballast in the hull and centerboards for lift. Notable designs include the MacGregor 26, Hunter 23.5 and 26, and the new Catalina 25. The idea is to dump the ballast on haul-out to minimize trailering weight, especially important given the small size of the average car these days. The drawback, as we see it, is that the water ballast works best when it is well outboard, which is the case on race boats with port and starboard ballast tanks. Trailer-sailers with shallow ballast tanks on centerline can’t obtain the same righting moments because of the short righting arm. Plus, saltwater is not very dense, just 64 pounds per cubic foot (62.4 lbs. for fresh), compared to lead at about 708 lbs. While waterballast may be a viable option for lake and protected-water sailors, we don’t think it’s the best solution.

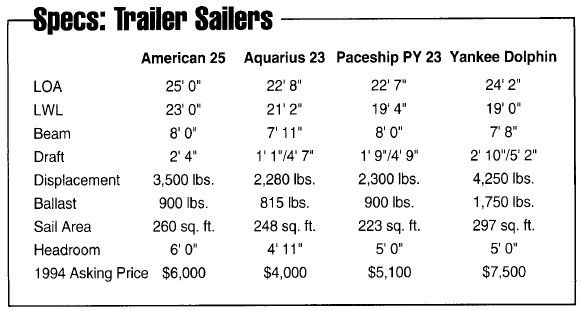

Looking back at the Paceship PY 23, American 26, Yankee Dolphin24, and Aquarius 23-we can examine several other approaches to the same problem.

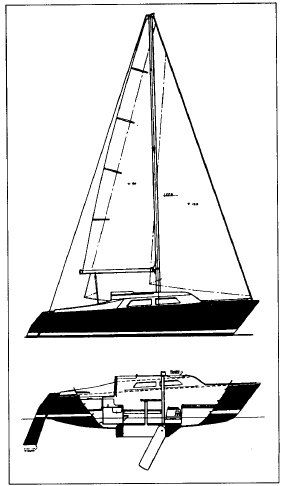

The PY 23

Paceship Yachts was originally a Canadian builder, located in Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia (it was later bought by AMF of Waterbury, Connecticut). One of its first boats was the popular East Wind 24, introduced in 1963. The PY 23, designed by John Deknatel of C. Raymond Hunt Associates, was developed in 1974 in response to the trailer-sailer boom.

An early brochure describes the PY 23 as “a second generation refinement of the trailerable concept which eliminates the awkwardness in handling and sailing often present in the early trailerables.” Indeed, the boat was rated 18.0 for IOR Quarter Ton and 16. 9 under the MORC rule. Modern looks were derived largely from the flat sheer and reverse transom.

Instead of the more common swing keel, in which all of the boat’s ballast hangs on a single pivot pin, Deknatel gave the PY 23 a 40-pound centerboard that retracts into a 900-pound “shallow draft lineal keel.” This arrangement eliminates a trunk intruding into the cabin space, and places the majority of ballast a bit lower (it draws 1′ 9″ board up) than in boats, such as the Aquarius 23, in which the ballast is simply located under the cabin sole. The downside is a bit more draft, which means you need to get the trailer that much deeper to float the boat on and off. (We once owned a Catalina 22, which draws 2′ 0″ keel up, and often had to use a trailer tongue extension-built in-to launch and haul out.) Based on our experience, any draft under 2 feet should be relatively easy to trailer and launch. Difficulties seem to mount exponentially with every inch of added draft.

Like most trailer-sailers, the PY 23 has an outboard rudder that kicks up for beaching.

Recognizing that trailer-sailers are not built for rugged conditions, and that by necessity they are not big boats, we herewith list some of the more common owner complaints: no backrests in cabin, barnacles in centerboard well, not enough room in head, not an easily trailerable boat, rudder rot, and poor ventilation in forepeak.

On the plus side, owners say the boat is quick, well built, balances well, has good-quality mast and rigging, a comfortable cockpit, and a livable interior.

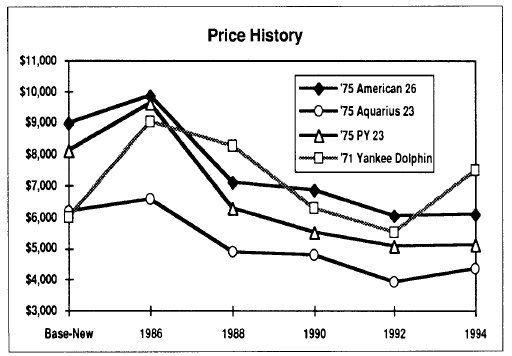

In all, we think this is a good example of the trailer-sailer. We like the keel/centerboard arrangement, even though it adds a few precious inches to board-up draft. It sold in 1974 for $8,150 base. Today, it would sell for about $5,100. A superior choice in our book.

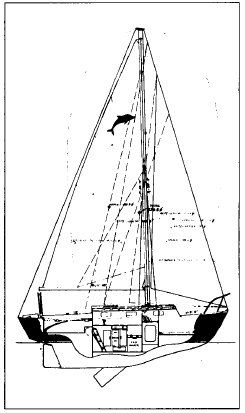

Yankee Pacific Dolphin 24

Yankee Yachts of Santa Ana, California, was a major builder during the 1970s, known mostly for its IOR boats. The Pacific Dolphin 24, designed by Sparkman & Stephens, is a classiclooking boat, not unlike the more familiar S&S-designed Tartan 2 7. It was built between about 1969 and 1971, when it was replaced by the Seahorse 24, designed by Robert Finch, who helped design the immensely successful Catalina 27.

The reason, we surmise, was that the Dolphin has a long keel drawing 2′ 10″, and though the company initially thought it would appeal to trailersailers, it’s draft, plus 4,250-pound displacement, made it difficult to launch and retrieve. In contrast, the Seahorse drew 1′ 8″, displaced 2,800 pounds, and has a scabbard-type removable rudder.

The Dolphin has 1,750 pounds of ballast, all in the keel. The attached rudder makes this boat a bit more rugged than most trailer-sailers, and its overall quality, including extensive teak joinerwork below, places it in a different category.

Owners report very few problems with the Dolphin other than a comparatively large turning radius, and cramped living quarters; most have only good things to say. An Oregon owner said, “Using a 3/4-ton pickup with a 390 engine we go uphill at 30 mph and down at 55. It takes us a couple of hours to rig and get underway, but it sure beats paying slip fees.” He also cites the Dolphin’s speed, saying he keeps pace with a Cal34, trounces a Balboa 26 and Catalina 27, and has only “lost” to a San Juan 21 going upwind. A Washington owner says she is very seakindly, with just the right amount of helm, though a bit tender due to narrow beam. Most owners use a 6-hp. outboard in the well, though one said he opted for a 15-hp. outboard for better performance, and because it can charge the batteries. Construction is reported as heavy.

In 1971 the boat sold new for $5,995.Prices now are around $7,500, which for an original owner would have made it the best investment of these four boats. While we have always liked the Dolphin, we don’t view it as suitable for regular trailering. More likely, you’d keep it at a slip during the sailing season, parking it at home on its trailer after haul-out.

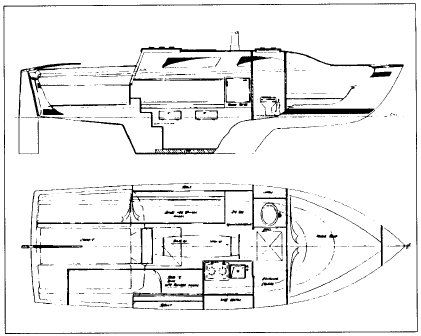

American 26

Costa Mesa, California was the epicenter of 1970s boatbuilding. American Mariner Industries is one company, however, better forgotten. It was in business from about 1974 to 1983. Its American 26 was a 25 first. A 1974 brochure says, “This 25-footer so completely justified our judgment as to the efficacy of our unique stabilizer keel and hull . . . that we have moved on to provide the trail-and-sail cruising enthusiast with a choice of two versions-the American 23 and the American 26.” This seems to imply that the same hull mold was used.

In any case, what is unique about this line of boats is the wide, partly hollow keel that makes a sort of trough in the cabin sole to provide standing headroom. It is not wide, but does run nearly the length of the main cabin. Ballast is 900 pounds of lead laid in the bottom of the keel. Draft is 2′ 4″ for trailerability, but there is no centerboard, and due to the keel’s extreme width, you can imagine that windward performance is poor. Unfortunately, we have no owner feedback on this boat to corroborate our assessment.

The boat sold new in 1974 for $8,995 base. The BUC Research Used Boat Price Guide says today it’s worth about $6,000. Frankly, this design, which severely compromises sailing performance for standing headroom, seems ill-conceived. One can only guess at how many people have cracked their skulls stepping up out of the trough.

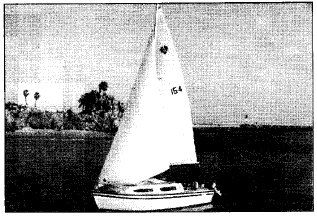

Aquarius 23

Coastal Recreation, Inc., also of Costa Mesa, was around from about 1969 to 1983. It acquired the Balboa line of trailer-sailers, and for a time built the LaPaz 25 motorsailer.

The Aquarius 23, and its smaller sistership the Aquarius 21, were designed by Peter Barrett, a Webb Institute graduate and national champion in Finns and 4 70s. The Aquarius 23 is not much prettier to look at than the American 26, though it sails surprisingly well. Because highway trailering laws restrict the beam to 8 feet, the Aquarius 23 comes in just under at 7′ 11″ and relies on it for stability. ” Most of the 815 pounds of ballast is in the hull. A large center- board retracts fully into a trunk, which is more or less concealed in the cabin as a foundation for the drop-leaf table. A peculiarity is that persons sitting at the table are all on the starboard side, and the forward person is forward of the main bulkhead, essentially in the head, though there is a fore-andaft bulkhead making the toilet reasonably private (another important issue for trailersailers).

Like the Paceship PY 23 and many other trailer-sailers, the Aquarius 23 has a pop-top to provide additional headroom. We think this is more sensible than the American’s keel trough, but we do caution that pop tops can leak and aren’t designed for offshore use.

Another unusual feature of the Aquarius is the absence of a backstay and spreaders. To support the mast, the shrouds are led aft, reflecting, we suppose, Barrett’s one-design background. If not suited for wild and woolly sailing conditions, it is at least simple to set up, and that, after all, is the goal of most trailer-sailers.

Friends of ours bought an Aquarius 23 in 1970, and we spent a good deal of time sailing with them, including several overnight crossings of Lake Michigan. The boat handled well, was reasonably quick on a reach, and had more interior room than most 23-footers. Still, we were never enamored of its looks.

Complaints from owners include lost centerboards and rudder repairs (like the Yankee Seahorse, it is an inside, removable type), poor ventilation, poor windward performance when overloaded, tubby appearance, and lack of a mainsheet traveler. Many owners say they bought the boat for its shoal draft and large interior, but that cheap construction caused numerous problems.

The Aquarius 23, in the early 1970s, sold for $6,195; today it sells for about $4,000. Though our memories of sailing this boat are all rosy, we think there are better boats available.

Conclusion

Our preferred solution to the keel/ ballast problem in trailer-sailers is the traditional keel/centerboard as found on the PY 23, Tanzer22 andO’Day23, all of which we recommend. The keel/ centerboard configuration eliminates the trunk in the cabin, places ballast below the hull, and does not concentrate all of the ballast weight on a pivot pin, as is the case with swing-keel designs.

We do not care for the American 26’s hollow keel, believing that if you want standing headroom, either go outside or buy a bigger boat. Nor do we care particularly for narrow shoal keels without centerboards, because windward performance suffers, or boards that leave all the ballast in the hull-whether lead, iron or water-as ultimate stability is compromised.

How one solves the choice between interior space and sailing performance is a personal decision. We, too, appreciate spaciousness down below, but at the same time have always chosen boats that looked and sailed decently, willing to give up a few inches of elbow room for a boat we could feel proud of when rowing away in the dinghy.

So the only real complaint against the Aquarius23 is the author is not “enamoured” with it’s “looks”, whatever that means.

I think the Aquarius 23 beats them all for what they were designed for. A family of 5 and thats just what I have. The wide stern and blunt bow make it Large inside and can take a lot of wieght in the tail. I need function, rugged keel for beaching and shallow waters.

I had an Aquarius 21 for thirteen years in San Diego. I sailed it all the time, and made four trips to Catalina Island in it. It had some poor constructions flaws (like particle board coring for the deck), but it was inexpensive, and easily handled by one person. I loved it.

Hi Kevin. I’m looking at a Aquarius 21 project boat. The owner lost the title so I would have to re-title it, but can find a VIN / serial # anywhere. Can you tell me where it might be located?

I have owned and sailed a PY 23 for twenty years, and she has served me well. I have had off and on trouble lowering the centerboard, as it easily sticks in the up position (likely due to growths inside the trunk). It is difficult to gain enough leverage from inside the cabin to force it down. Other than that – the boat has been a trooper.

Have you ever evaluated the Sirius 21/22?

How about a review of the Sirius 21/22 by Vandestad and McGrewer?