After Leon Slikkers sold Slickcraft, his powerboat company, in the early 1970’s, he built a sailboat factory the way a sailboat factory should be built. The result was S2 yachts and a factory quite in contrast to the normal dingy warehouse with blobbed polyester resin hardened on rough concrete floors.

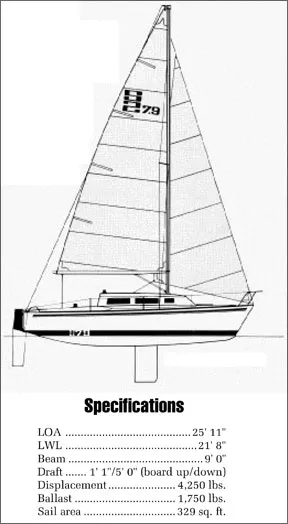

Originally known for cruising designs, S2 Yachts opened their second decade in business by entering the high performance field, building first a trailerable racer/cruiser, the S2 7.9. The 7.9 stands for meters, which translates into American as 25′ 11″. The boat stayed in production up until S2 shut down its sailboat operations in 1986.

Designed by the Chicago-based naval architects Scott Graham and Eric Schlageter, the 7.9 was the first in a series of competitive production boats. The series was originally called “Grand Slam,” but the company later dropped the designation. With over 400 built between the boat’s introduction in 1982 and 1986, the 7.9 was relatively successful during a time when few boats in its size range were selling.

The 7.9 was a pricey boat for her size. Equipped with sail handling gear, four sails (main, jib, genoa, and spinnaker), outboard motor, speedo, and compass, her 1985 price was about $27,000. For comparison, a comparably equipped J/24 of the time would run you around $21,000, an Olson 25 about $22,000. Add an inboard engine, a trailer, and miscellaneous gear and you could easily have dropped $36,000 on the 7.9—a hefty tab for a 26′ boat.

Construction

The hull and deck of the 7.9 are hand-laid fiberglass, cored with end-grain balsa. S2 bragged about its glasswork, and the company had a high reputation in the industry for both its gelcoat and its hand layup.

Beginning somewhere around hull number 400, S2 switched from conventional polyester resin to a modified epoxy resin—AME 4000. The company claimed the epoxy resin is stronger, lighter, and less subject to blistering.

The hull is fair with no bumps or hard spots evident—probably the result of the company’s practice of installing most of the interior before removing the hull from its mold. The gelcoat appears to be thicker than is usual in production boats—a good

feature since minor scratches and dings can be “rubbed out” without penetrating to the laminate.

For their standard hull-to-deck joint, S2 used an inward turning flange onto which the deck molding is set—a desirable design, especially when bedded in flexible adhesive (such as 3M 5200) and through bolted at close intervals. However on the 7.9, rather than being through bolted, the deck is mechanically fastened to the hull only with screws through the slotted aluminum toerail, a detail that indicates the boat is not intended for heavy-duty offshore work.

The boat came with a one-design package of good quality deck hardware. All hardware is through bolted, with stainless backing plates on the lifeline stanchions but with only washers and nuts on all other hardware. This would seem to be problematic with the balsa core, but we have heard no reports of problems so far.

Although the company offered the boat in a fixed keel version, the vast majority of boats have a lead ballasted daggerboard.

The advantages of a daggerboard are, first, that it retracts to be flush with the bottom of the hull to make the boat trailer launchable, second, that you can float the boat in a mere 13″ of water (though she will have no directional control with the board totally up—you’ll need at least a foot of board showing for control under sail or power), and, third, with the board totally down, the boat has a 5′ deep hydrodynamically efficient keel, a depth that would be extreme on a fixed-keel boat this size.

The disadvantage of the daggerboard will come in a hard grounding. Whereas a centerboard would kick out of the way, the board is likely to bash around a bit in its trunk. A nice detail by S2 is that the bottom opening of the trunk is surrounded by a strong weldment which will mitigate the potential damage to the hull from a grounding. Another potential disadvantage is that, on many boats, the daggerboard trunk messes up the interior, but the designers have done a good job on the 7.9, incorporating the daggerboard into a centerline bulkhead.

Nearly a third of the 1,750 pounds ballast is in the board, with the remaining two-thirds glassed to the interior of the hull. When the board is fully lowered, it fits snugly in a V-Shaped crotch—a good design detail—but when it’s raised out of the V using the three-part tackle and winch, it will bang about loosely in the daggerboard trunk. There is no way to pin the board down—an obvious potential problem in severe conditions.

The boat, however, has passed the MORC self-righting test with the daggerboard in the fully raised position. In the test, the mast-head is hove down to the water, the bagged mainsail and genoa are tied to the masthead, and the whole shebang released. This is not a test of ultimate stability, since other boats which passed the test have turtled and sunk, but it is reassuring. However, the design is clearly dependent mostly on its beamy hull form for righting and not on its ballast—another indication the boat is intended for close-to-shore sailing.

The transom-hung rudder—pivoted for trailering—is of foam-cored fiberglass (the foam gives it neutral bouyancy in water). We like the idea of a transomhung rudder: it’s accessible for inspection and service, it lessens the potential damage to the hull that can occur when a rudder smashes into something, and it gets the rudder farther away from the keel to give the tiller a more responsive feel.

The fractional rig—with mast and boom made by Offshore Spars—is dinghy-like, having swept-back spreaders which make the upper shrouds function as backstays. The actual backstay does virtually nothing to support the rig; instead, its primary function is to bend the mast to control mainsail performance. Although the mast is easily bendable, it’s a surprisingly heavy section for a modern racing rig—it’s also untapered. Everything is internal in the mast and boom, with all lines eventually coming back to the cockpit in typical modern racing style.

Upper and lower shrouds attach to inboard chainplates. The starboard chainplate is attached to a well bonded plywood bulkhead, but the port chainplate is longer, attached to the fiberglass structure which forms the front edge of the galley. Since there is a 2′ “free span” of unsupported chainplate between the galley and deck, the chainplate in the highly-loaded rig works a lot, and one of the most common owner complaints about the boat is the leaking port chainplate that results.

A fiberglass floorpan makes up the berths, floor, and galley area. Instead of a ceiling, S2 uses carpeting for interior covering of the hull. One good detail about the carpeting is that Velcro will stick to it—you can hang anything anywhere—but we have to wonder how the carpet will stand up to salt accumulation. There is virtually no bilge, so water inside will turn everything soggy.

Generally, the boat is well constructed, with good detail work and hardware. While we believe that every “racer-cruiser” should be designed and built to handle extreme conditions offshore, the hull shape, the daggerboard design, and the hull-to-deck joint show us that S2 did not intend for this boat to be involved in those extremes.

Handling Under Power

The standard 7.9 is be outboard powered. The option was a BMW 7.5 hp one-lung diesel with the shockingly high price tag of $5400 new. When BMW got out of the marine business, S2 offered the boat with the 7.5 hp Yanmar.

The little diesel handles the boat well, though owners report that it will not punch through a heavy headsea. This is probably more the result of the folding Martec prop which comes as part of the inboard package rather than any lack of power in the engine.

The inboard installation is well done. The ply-wood stringers glassed to the hull support vibration-damping mounts for the engine. Standard installation includes a stainless steel eight gallon fuel tank, properly grounded, a heavy duty Purolator filter/water-separator, a waterlift muffler, and single-lever shift/throttle controls.

Both the fuel shut off and the fuel filter are difficult to get to—through an inspection port in the port quarterberth—but access to the engine is otherwise good, with hinged companionway steps opening out of the way so dipstick, decompression switch, engine controls, water pump are easy to get at. For more serious work on the engine, the quarterberth panels are removable for virtually total access. One good feature of the BMW is that it is the one engine we’ve ever seen that is actually easy to start by hand cranking. It made S2’s one-battery installation workable. With the Yanmar, owners may want to look for a place to stow a second battery; offhand, there’s no obviously good location.

As you might expect on a 4400 pound boat, the outboard is minimally adequate except for backing up and except in any wind or sea conditions. We would normally recommend the inboard for the 7.9, but there is a problem—the underwater drag of the shaft, strut, and propeller—an important consideration for the racer.

Our conclusion is that the serious racer should probably look for the outboard model and just suffer the poor performance under power. If you will be primarily daysailing, weekending, and cruising, we recommend the inboard.

If you’re planning a combination of racing and cruising, you’ll just have to make a judgment which aspect you want to emphasize.

Handling Under Sail

The 7.9 is a proven performer under sail, being not only a fast boat for her size but also competitive in handicap racing under MORC and PHRF. Her PHRF rating of 168 says that she’s about the same speed as the J/24, Merit 25, and similar current racing boats, and about the same speed as such older racer-cruisers as the Pearson 30, Cal 34, Catalina 30 tall rig, or Irwin 30.

With her narrow entry forward, a big fat rear end, and a fractional rig with most of the power in the mainsail, she will be better behaved than her high-performance cousins designed to the IOR rule. Owners report that her one bad habit is to wipe out in heavy puffs when beating.

Her dinghy-shaped hull means she’ll have to be sailed flat for best performance, which in turn means lots of lard on the rail when the wind pipes up. Five people, the heavier the better, is de rigueur for heavy air racing.

For daysailing and cruising, she’s got plenty of reefable sail area, and she should perform well with the four standard class sails: main, 155% genoa, 105% jib, and spinnaker.

Peak performance will take lots of tweaking and fiddling with the rig. This will be no problem for the high-performance dinghy sailor graduating to a cruising boat, but it will take a lot of learning about mastbend and sail shape for the newcomer. Nonetheless, even when not tuned to perfection, she should perform well enough to be a pleasant daysailer for the weekend hacker.

Deck Layout

The 7.9’s inboard shrouds, wide decks, and big cockpit will make for pleasant moving about on deck. The nonskid is good—among the best we’ve seen in a production boat. It will remove skin from bare knuckles.

The boat will be sailed from the cockpit, and she’s well laid out for sail handling. The primary winches are, if anything, oversize—a true rarity these days—and the secondary winches on the cabin top are adequate for halyard and spinnaker work. (Note, though, that the lead daggerboard is raised and lowered using the starboard secondary winch. One of our readers reports blowing up the winch; another says, “The #16 winch is inadequate for a woman or small man to handle the board.”)

Like the J/24 and other performance boats, the helmsman and crew will sit on the deck rather than in the cockpit when racing. However, unlike the J/24, the 7.9 does have a true cockpit, and it’s comfortable. The seat bottoms are slightly concave, the seat backs are nearly a foot high and contoured to support the small of the back, and seat-to-sole distance gives comfortable leg room. The mainsheet traveler is smack in the middle of the cockpit and will prove a shin ravager until you get used to it. But, the cockpit will comfortably daysail six and drink eight at dockside and is definitely a strong point for the boat.

There are two substantial cockpit lockers for stowage. Several owners report that the lockers leak—a nuisance in what appears to be an otherwise dry boat.

Belowdecks

As one owner puts it, “The interior does the best it can.” With about 5′ 4″ headroom, the cabin will require stooping for most people. Still, we admire S2’s restraint—they could have easily added 6″ to the doghouse to get “standing” headroom. And to get a boat that would be as ugly as some of their early cruising models.

S2 was not suckered by the how-many-does-shesleep syndrome for this model. Both quarterberths are long and wide, and the forward V-berth is truly sleepable with the boat dockside or at anchor. The only drawback to the arrangements is that the space between berth and side decks is so short that sitting upright will be uncomfortable for anyone over 6′.

The galley (or, more accurately, the galley area) is absolutely minimal, with a shallow sink and small icebox. There’s a tiny counter area—either for counterspace or for a one-burner alcohol stove—but anyone wanting to weekend or cruise with more than PB&J’s will have to revamp the galley.

The daggerboard trunk is well disguised, forming one wall of the head. The head itself is cramped, to say the least—you can sit on the Porta Potti, but your knees will stick out through the privacy curtain. Still, the head location is preferable to the all-too common position under the V-berth.

Ventilation below is nonexistent. Opening ports were available as options. A small quarterberth opening port or a forepeak vent would be desirable. Compared to a larger boat’s “yacht” finish or even to a 25′ cruising boat, the 7.9’s interior will seem plain and functional.

On the other hand, it’s luxurious compared to a J/24, J/27, Merit 25, or Evelyn 26. The boat can be weekended in comfort. If you can stand camping out, the boat can even be cruised.

Trailerability

With a 9′ beam, the 7.9 is not legally trailerable in any state without special wide-load permits. Yet most of the boats have been sold with trailers, and the company boasts of its trailerability and easy launchability. How is this possible?

The consensus is that, with the daggerboard retracted, the boat sits so low on the trailer that it doesn’t look that wide. A keelboat on a trailer—a Merit 25, for example—looks much bigger and a bored cop is more likely to stop and measure a keelboat than a 7.9. At any rate, 7.9s are trailered, and we know of none ever being ticketed or, for that matter, even questioned.

Conclusions

S2 did a good job of aiming the boat at a variety of sailors: racers, daysailors, and weekenders.

For racers interested in a one-design boat, the class is not strong outside the Great Lakes. But for the sailor into handicap racing, the boat seems a good possibility. It’s definitely competitive in MORC and PHRF fleets. And unlike other high-performance boats its size—the Olson 25, J/24, Merit 25, Evelyn 26, or Capri 25—the 7.9 is a boat you could stand sleeping aboard or taking on a rainy overnight race.

For the sailor primarily interested in daysailing and weekending, the 7.9 will also be worth serious consideration. She is definitely on the pricey side for 26′ boats, but her quality construction and equipment are what you get for the extra money. She may be a little on the high-performance side for the real novice, but her four-sail class package should be fairly easy to handle even for the newcomer.

We really could not recommend her as a cruiser. Well, maybe as a pocket cruiser. S2 clearly didn’t intend her for cruising or offshore sailing; still, she’s well made, a fast boat, and maybe if our seamanship were good enough…but no, if it’s a fast cruiser we’d like at 25′ to 26′, we’ll keep looking.