Many sailors consider multihull sailing to be on the fringe of our sport. If that is true, then the Stiletto catamaran is dangling one hull off the edge. It’s hard to mistake her appearance, with blazing topside graphics and aircraft-style, pop-top companionway hatches. It’s also hard for the average sailor to appreciate the sophistication of the Stiletto’s construction—epoxy-saturated fiberglass over a Nomex honeycomb core.

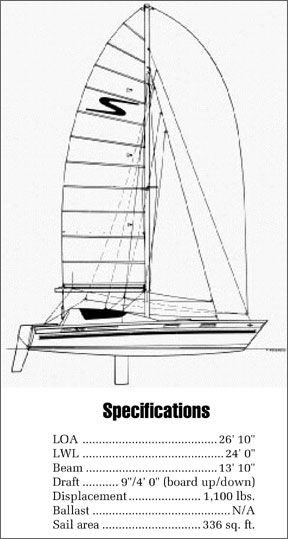

The 26′ 10″ Stiletto is anything but conventional. Multihulls larger than 20′ can usually be classified into one of two genre. The largest group is that of the “cruising” multihull, characterized by beamy hulls, with a cabin house across the bridgedeck, stubby undercanvassed rigs, and monohull-like displacements. They often have mediocre performance, and are sometimes regarded with embarrassment by multihull enthusiasts.

The other genre of large multihulls is characterized by light displacement, powerful rigs and lean interiors. Custom ocean racing trimarans fall into this category, as do a very few production catamarans like the Stiletto.

The Stiletto’s builder touted her trailerability, “scorching performance” and “cruising comforts.” She is supposed to be the next step for the sailor weaned on small high-performance catamarans. In fact, three of the five owners we spoke to were former Hobie 16 sailors.

Almost anyone can understand why catamarans like the Hobie 16 are so popular—they offer breathtaking performance without making great demands on a sailor’s expertise or pocketbook. To step up to a Stiletto is expensive, however. She was offered in three versions, along with a 30′ version introduced in 1983. For $17,950 in 1982, the Standard Stiletto had a mainsail and all but stripped interior and no options. The racing version, called the Championship Edition, came with a few options like deck hatches, rubrails and removable berths, plus extra racing sails, winches and a knotmeter; it cost $22,900. The cruising version, called the Special Edition, cost $24,900. That healthy chunk of cash bought the boat equipped with the options needed for pocket cruising, such as galley, head, berths, carpeted interior and running lights. Most Stilettos are Special Editions, followed by Standards and Championships.

Force Engineering (later Compodyne), a small, high-tech outfit in Florida, formed to build the Stiletto in 1978. Before he joined Force Engineering, co-owner/marketing director Larry Tibbe was an aircraft account salesman for Ciba-Geigy, a manufacturer of Nomex. Nomex coring is used in a variety of aircraft parts (for example, helicopter blades), as well as for the Stiletto’s hulls. Force’s survival strategy included the manufacture of several non-marine products out of Nomex, which helped them survive some bad times.

Construction

Very few boats are cored with Nomex honeycomb as are the Stiletto’s hulls and bridgedeck. Sandwiching a core material between two layers of fiberglass laminate is not a new technique; many boatbuilders use cores of balsa wood, Airex foam or Klegecell foam. Core construction offers several advantages over single-skin construction. It is stiffer for a given weight, lighter for a given stiffness, makes the boat quieter and reduces condensation.

Honeycomb is rarely used for boatbuilding because the molding procedure is far more sophisticated (and expensive) than with balsa or foam cores. Honeycomb can be made of several materials. We question the use of paper or aluminum honeycomb in boats, because of their susceptibility to water damage should the outer laminate of the core be ruptured. The Stiletto’s Nomex honeycomb core is made of nylon.

Force Engineering stated that a Nomex honeycomb-cored panel, for a given weight, is stronger, stiffer, less brittle and more puncture resistant than foam or wood cores. Nomex is also said to be impervious to water, so there would be no water migration between the honeycomb cells should the outer skin be ruptured.

These grandiose claims depend on a sophisticated and expensive molding procedure. Getting the honeycomb to bond to the fiberglass skins isn’t easy. First, Force Enginering buys its fiberglass cloth preimpregnated with epoxy resin. Most boat builders use polyester resin, which is an inferior adhesive, and saturate the fiberglass after it has been laid into the mold—a messy and inexact procedure. Preimpregnated cloth, or “prepreg,” has an exact resin-to-cloth ratio, which means that the builder always has the optimum strength-to-weight ratio. Most boat builders must err on the resin-rich side when saturating cloth, which increases weight but not strength.

To keep the prepreg cloth from curing before it is laid into the Stiletto mold, it must be shipped and stored in a refrigerator. To completely cure the prepreg after layup, the mold is placed in a modular oven and baked at 250 degrees for 90 minutes. At the same time, the fiberglass skins are vacuum-bagged to the honeycomb to ensure proper adhesion. Vacuum-bagging cored hulls is not a new technique, but for many builders it simply means laying a sheet of plastic into the mold and sucking the air out with a single pump (polypropylene line is often placed under the plastic to help distribute the vacuum).

Force Engineering uses a blotter to absorb any excess resin and 16 spigots to distribute the vacuum, a more effective technique. When finished, each of the Stiletto’s hulls weighs only 220 lbs. and is impressively strong and stiff.

The Stiletto’s hull and bridgedeck may be state-of-the-art, but the rest of her rig, like her aluminum mast and crossbeams, is built with conventional (and relatively heavy) technology. All-up, the Stiletto weighs 1,100 to 1,570 lbs, depending on optional equipment.

We wonder whether building the Stiletto of Nomex is worth the extra trouble and expense, or if she is being used as a platform to prove the material’s viability. Gelcoat cannot be used in the Stiletto’s molding process. instead, each boat must be faired with putty and painted with polyurethane. Paint has the advantage that it will not chalk like gelcoat, but it is more susceptible to nicks, scrapes and peeling, especially if improperly applied.

The Stiletto’s optional hull graphics are sticky-backed vinyl. Both the paint and the graphics were chipping on one five-year-old Stiletto we looked at.

The spars and the crossbeams are also painted with polyurethane. Although Force says it carefully sands and primes the spars, several of the masts we looked at had adhesion problems. The fittings were unbedded. The crossbeams were not anodized, and were only painted on the outside. Water can get inside the beams and accelerate corrosion.

The deck rests on an inward-turned hull flange, a common, safe design. But the deck is only epoxied to the hull without screws or bolts, inviting separation in the event of a catastrophic collision. Epoxy is undoubtedly stronger than polyester. However, we prefer mechanical fastenings in addition to a flexible adhesive like 3M 5200.

The Stiletto has a single daggerboard that is mounted on centerline through a slot in the bridgedeck. It is held snugly in place by a latticework of stainless steel tubes extending downward from the underside of the bridgedeck. This daggerboard frame is designed to collapse in the event of a hard grounding. There is no chance of the hull rupturing, as there would be with a daggerboard trunk built into the hull itself.

The Stiletto’s single board is not as efficient as the dual boards found on other catamarans, and the board’s support frame does tend to drag in the water while sailing. To keep water from squirting through the bridgedeck slot, the slot is covered by cloth gaskets. The gaskets occasionally jam.

The Stiletto has an airfoil daggerboard. Older models were made of wood, and chipped trailing edges were a common problem, The board is molded of fiberglass and more resistant to minor damage.

The Stiletto gets high marks for her rudders. They have strong aluminum heads and double lower pintles. To be beachable, a catamaran must have kick-up rudders; these kick-up systems often refuse to work when you need them most. However, the Stiletto’s rudders worked smoothly and positively.

The Price of Performance

Multihulls are separated from the monohull mainstream by several things (in addition to the number of hulls). The first is performance. Multihulls, particularly catamarans, are lighter, more easily driven and hence far more exhilarating to sail than most monohulls. Yet even a novice can enjoy catamaran performance in most wind conditions because of the tremendous initial stability that a catamaran’s beam offers.

The flip side of this hot performance is safety. Catamarans also have tremendous stability after they have capsized and turned turtle. All but the smallest catamarans are nearly impossible to right after they have gone completely upside down, especially if the mast is not airtight.

When reaching in strong winds, many catamarans have a nasty tendency to bury the leeward hull and pitchpole. Some cats can even be blown over backwards if a very strong puff catches the underside of the trampoline. Nearly all trimarans that are raced

offshore have watertight hatches on the bottom of the main hull to allow escape if the boat flips over.

Another price of performance is comfort. Multihulls tend to be wet. When you’re flying along at 20 knots, even a light spray can feel like a fire hose. It’s harder to find a comfortable spot to relax in when you’re sailing. The trampoline/bridgedeck separating the two hulls of a catamaran is usually flat—you sit on it, not in it. Moreover, the hulls of a thoroughbred multihull are narrow, so there is little space in which to put creature comforts. The wide-hulled, cabin-housed “cruising” catamarans are no more spritely than a monohull of similar displacement.

Multihulls are also less maneuverable than monohulls. They can be difficult to tack without getting into irons, and they have a much wider turning radius. Sailing in a crowded harbor takes greater care.

Trailerability

Force Engineering emphasized the Stiletto’s trailerability. True, she is light enough to be pulled by a modern automobile of modest power. But all of the owners we talked to said they rarely, if ever, trail their boats. 80% of the boats were sold with trailers, but it appears that most are used only for winter storage.

Rigging and launching the Stiletto is not a simple chore, despite the fact that the builder claimed a man and woman can do it in only 45 minutes. Owners say it takes at least several men well over an hour to do the job. The Stiletto has a beam of 13′ 10″; legal highway trailering width in most states is 8′. To solve this problem, both the Stiletto’s crossbeams and the trailer collapse to legal width. The compression tube that spans the bows must be removed for trailering, as must the dolphin striker beneath the mast step, and the 125 lb bridgedeck.

To raise and lower the mast, the headstay is shackled to a short, pivoting gin pole mounted just aft of the trailer winch. The winch is used to pull the gin pole, which in turn provides leverage to hoist the heavy mast. Owners say that lifting the bridgedeck and manhandling the spar is next to impossible with just a man and woman. The Stiletto assembly manual points out, “…she never fails to draw a crowd, so help is usually available if you are shorthanded.” As long as you have the muscle, this clever system does work.

Sailing

The Stiletto is a performance catamaran. In a breeze, owners report, she is as fast or faster than a Hobie 16, but a bit undercanvassed in light air, especially with her 106 square foot working jib. This is preferable to over-canvassing; a catamaran of the Stiletto’s size cannot afford, for safety’s sake, to be a bear in heavy air.

According to owners, the Stiletto does not have some of the bad heavy air habits of smaller catamarans. They say she is relatively dry to sail, does not hike up and “fly a hull” too easily, has no tendency to pitchpole, and does not get “light” as she comes off a big wave sailing upwind. Like most catamarans, the Stiletto has a fully battened mainsail. The advantage of these sails is that they can have a much larger roach, and because the battens dampen luffing, the sail will last much longer. However, this inability to luff can present a real safety problem in a sudden squall. It is prudent to reef when the wind reaches 20 knots. A smaller roached, short-battened cruising mainsail is available as an option for offshore cruising. The sails that came as standard equipment seem to be of better than average OEM quality.

Stiletto sailors told us that they sail very cautiously in a strong breeze, knowing the dangers of capsizing so large a multihull. Once capsized, a catamaran turns turtle (completely upside down)very quickly. A turtled multihull with a mast full of water is nearly impossible to right. The Stiletto’s builder offers a self-righting kit as an option, but they have sold very few. The kit consists of a bulky foam float permanently mounted to the masthead, and a 17′ righting pole stowed under the bridgedeck. The float is supposed to prevent the boat from turning turtle while the righting pole is extended outward and its three stays are rigged to the underside of the boat. Then two crew swim out to a ladder dangling from the end of the pole, climb up to right the boat, then quickly swim free before the ladder drags them 17′ toward Davy Jones’ Locker. It’s no small wonder that the self-righting kit is not a popular option.

Force Engineering points out that the air cells of her honeycomb construction make her unsinkable in the event of a holing or capsize. However, they do not point out that once the hull is flooded, the boat cannot be sailed or motored home without inviting the flooded hull to submerge and pitchpole the boat. The Stiletto, like most high-performance catamarans, has a rotating mast. Owners say they have not had problems with the mast popping out of rotation while sailing upwind. The older masts have only athwartships diamond shrouds; the newer masts have an added third diamond extended forward to control fore-and-aft bend in a strong breeze. This three-diamond system is strongly welded together and a real plus for heavy weather sailing.

Deck Layout

The Stiletto has a solid bridgedeck stretched between the two hulls aft of the mast, and a polypropylene cloth trampoline forward of the mast. Those few sailors planning to venture offshore might want to remove the trampoline, lest it collect water in heavy seas. On Stilettos older than two years, the trampoline is laced with a series of hooks. On the newer boats the trampoline has bolt rope edges, and slides into tracks on the hull and crossbeams, a simpler and cleaner system.

The bridgedeck, which is where you spend most of your time, has no seats and is said by several owners to be uncomfortable. Because of this, the temptation when sailing is to sit on top of the flimsy companionway hatches. We feel that a “cruising” catamaran should have proper seats with angled seatbacks.

A wire stretched between the bows forward of the headstay acts as a traveler for the optional reacher/ drifter. Most sailors opt for this sail before they buy a cruising spinnaker. Poleless cruising spinnakers are more effective on a catamaran than on a monohull because they can be tacked on the weather hull, away from the blanketing effect of the mainsail. A roller furling headsail with a Hood Seafurl system was an option. Headsail winches were standard on the Championship Edition, otherwise they were an extra-cost option. A main halyard winch, which owners recommend, was another.

The Stiletto has a ball-bearing mainsheet traveler, a worthy item rarely found on catamarans. But the mainsheet has only a 6-to-1 purchase, which owners say is insufficient in a breeze. The tiller extension passes behind the mainsheet and the tiller crossbar is adjustable so you can align the two rudders. The jibsheets are led to Harken ratchets to make trimming easier. The outboard engine bracket is hung off the aft compression beam.

Interior

Those of you who have peeked below on the Stiletto might ask, “What interior?” It’s a valid question. The Standard Stiletto version is nothing but an empty shell below. Depending on the care that was taken during the vacuum-bagging process, the interior hull surface can be smooth or quite rippled. Either way, the Nomex gives the boat a long-lasting smell similar to mouse droppings (we could still smell it on a five year old boat).

The popular Special Edition was described by the builder as a “luxury coastal cruiser”; though it cost nearly $25,000 new, we would be more comfortable on a Catalina 22. The Special Edition’s interior is completely covered—ceilings, overhead and sole—with Aqua Tuft marine carpeting. Owners say it is durable and does not mildew, but we feel carpet belongs in a house, not a boat.

The Stiletto has the narrow hulls of a fast catamaran, which means that her berths are only 31″ wide. The Special Edition has 14′ of built-in berth forward of the companionway in each hull. For two people to sleep easily in a berth, they have to lie end-to-end.

Crawling toward the bow to get to the forward berth is like crawling down a narrowing tunnel—it gave us claustrophobia. If a normal-sized couple really wanted a good night’s sleep, they would have to bed down in separate hulls. There is some stowage area under the berths, but access to it is just plain difficult.

The Special Edition has a self-contained head under one berth. A pump-out head was not an option. The Special Edition also has a small galley built of “marble finish” plastic laminate over plywood; we think that even the most “with it” cat sailor would consider it gaudy. The galley has a sink with a hand pump and a two-gallon water tank. There is no permanently mounted stove; a portable stove is more practical for the weekend cruiser.

An option that we recommend is the mosquitotight bridgedeck tent. The bridgedeck cushions that are standard on the Special Edition should make the tent, and hence the whole boat, somewhat livable. The Special Edition is also the only version of the Stiletto that has running and interior lights.

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the Stiletto is her conical companionway hatches (“canopies,” as in jet fighter-like). It’s hard to be impartial about their appearance—you either like ’em or you don’t. We don’t. The canopies are formed of dark, bendy plastic. They open vertically like a pop-top hatch, and swing on flimsy aluminum tubes that are not well secured to their mounts.

Owners say the canopies are watertight, but the rubber gaskets in which they sit were rotting badly on the older boats we saw. For that matter, the rubber gaskets on the bridgedeck were rotting, too. Trying to sleep in the Stiletto’s hulls could be very stuffy on a rainy night. Because the canopies rock forward as they “pop-up,” it’s hard to leave them open a crack like a conventional hatch, and there are no companionway boards.

Conclusions

There is probably no production hull built in the US with a better strength-to-weight ratio than the Stiletto catamaran. Her Nomex honeycomb fabrication is truly impressive. But is it necessary? Just as some builders “overkill” with heavy solid laminates, we feel that Force Engineering overkilled in the other direction. Conventional coring probably could have created an adequately strong and light boat that would have provided just as much sailing fun for less money.

The next question is, “What do you do with her?” The Stiletto seems to appeal to the catamaran sailor hooked on high performance, but who wants a boat in which he can “go someplace.” The Stiletto is quick, but she won’t get someplace any faster than a small catamaran. She may be dryer, but she still lacks comfortable seating and sleeping. When you get to where you are going you have very little comfort for the money you’ve spent on the boat. And when you get home, you have a considerable chore ahead of you if you plan to load her onto a trailer.

All the owners we talked to said they love the way the boat sails and have no complaints about her construction. Yet we still don’t feel the Stiletto is practical. There are other, less expensive options for the multihull sailor who wants to weekend cruise. Any catamaran can be rigged with a tent on the trampoline/bridgedeck. Inflatable air mattresses stow easily and make fine temporary berths. And some catamarans, such as the much-less-expensive P-Cat 2/18, have the dry stowage in their hulls to carry camping supplies. Small catamarans are ultimately safer, because they can be righted from a capsize, and they are infinitely easier to trailer.