Don’t ask an adhesive to do more than it can. If a bolt breaks, we accept it as deterioration or faulty design, not a defective bolt or the fault of bolts in general. And just as there are good and bad applications for bolts, there are inadequate adhesive joint designs.

• Avoid bonding materials of significantly different flexibility. It’s like tug of war with a bungee cord, and not being able to move your feet; only the first guy feels the load. If one material stretches more than the other, the load is not equally distributed and the adhesive will fail from one end, sort of like 3M Command strips. Either use a mechanical coupling (bolt or shackle), or stiffen the flexible material by increasing thickness (more layers). Also avoid bonding like materials under conditions where one will stretch more than the other due to greater stress level.

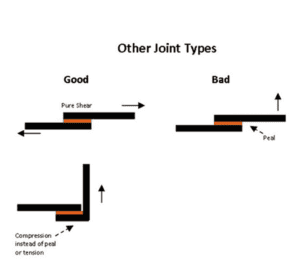

• Peeling is like bonding flexible materials; only the first fraction of a millimeter holds any load. If peeling force is unavoidable, use mechanical fasteners to take the peeling force.

• The flexibility of the bonding agent should be matched to the more flexible material. Epoxy and MMA for stiff materials, urethanes and silicone for things that flex.

• If the bond agent must have some flexibility and a mechanical fastener cannot be used, increase the bond area until the sealant does not have to stretch more than a few percent of its elongation to break; stretch cycling results in peeling and bond failure.

• Thermal expansion. Differential thermal expansion can bring high stresses. Glazing is the classic case. The thick bond area and flexible adhesive can compensate, a thin bond line will be highly stressed. The joint thickness must be uniform with no thin areas (use spacers).

• Movement. If there must be movement, then there is a minimum joint thickness; no matter how flexible the adhesive is, if it does not have space to work (thin spot in the joint) it will tear. This is a real hidden bugger, because hidden somewhere within the joint there may be zero thickness. Like glazing, the joint thickness must be uniform with no thin areas (use spacers).

• Uniform joint gap. With flexible adhesives, the strength is reduced if the gap is variable. Because varying percent stretch of the adhesive, the wide spots don’t carry as much load as narrow spots, resulting in reduced strength. It’s best to figure at least a 50% reduction for any joint that is not perfect, and 75% reduction if the thickness is near zero in any area (bolted tight).

• Point loads. Highly concentrated loads are typically carried by fasteners (through bolts) with a very soft sealant such as butyl used only as a bedding agent. If the sealant is stretched beyond its working limit it will fail. (Working limit is at least five times less than elongation to failure, which after inevitable stiffening, is many times less than the stated value.) Some points in the bond area have almost no elasticity, so any measurable movement will cause failure at that point. Chain plate seals and most deck hardware involve this type of joint.

Joint area. Weaker adhesives can be made to work by increasing the bond area. However, peeling becomes a problem, as does load distribution. Joint area must be enough for the service and the type of stress (tension vs. sheer vs. peeling).

EXAMPLES

Backing plates. Several approaches work. The area can simply be reinforced by laying up more glass and skip the backing plate. A stiff adhesive (epoxy) is used to laminate the stiff glass fibers. Differences in flexibility between the deck and plate area are reduced by tapering the plate’s edges. A rigid plate (metal or pre-laminated FRP) can be installed using flexible adhesive; the bolts hold the shear and load and the sealant distributes the compression load across the area. Bedding under the hardware alone will result in uneven loading, higher stresses and an increase likelihood of leaks. (See “How Big Does a Backing Plate Need to Be?” PS August 2016.)

Chain plates. Chainplates call for a flexible sealant because of the movement at the joint. This movement and extreme compression at this joint makes leaks inevitable as the sealant ages. Use substantial chain plates that reduce stretching, and, if possible, stiffen the deck so that it does not move independently from the chainplate. A wide gap gives a flexible sealant room to stretch.

• Composite chainplates. Composite (usually carbon-fiber) chainplates eliminate the need for any sealant here. Unidirectional fibers are wrapped around a mandrel and then splayed along the hull. Because there is no abrupt change in stress, the hull and chainplate move as one, so a stiff laminating glue (epoxy) works well here.

Hull-to-Deck Joints. In principle, bonding GRP to GRP sounds like a job for epoxy. But if you bump a dock or fall off a wave just right, there may be enough momentary stress to crack the epoxy bond. A more flexible adhesive, like 3M 5200 will give a little, but it has poor resistance to peeling, requiring bolts for backup. It also has a service life, and as it nears the end it becomes stiff and can lose its grip.

Methyl methacrylate adhesives (MMA), such as Plexus have a loyal following among boatbuilders for their strength, gap filling ability, slight flexibility, and durability as hull-deck glue. It will also work for hull-deck joint repairs.

You will need to open the joint and clean it the best you can. This also suggests MMA, since it is the most tolerant of poor surface preparation, although polyurethane sealants are popular. Epoxy is a poor choice because of stiffness and surface preparation limitations. Adding a few through bolts for clamping is a good call.

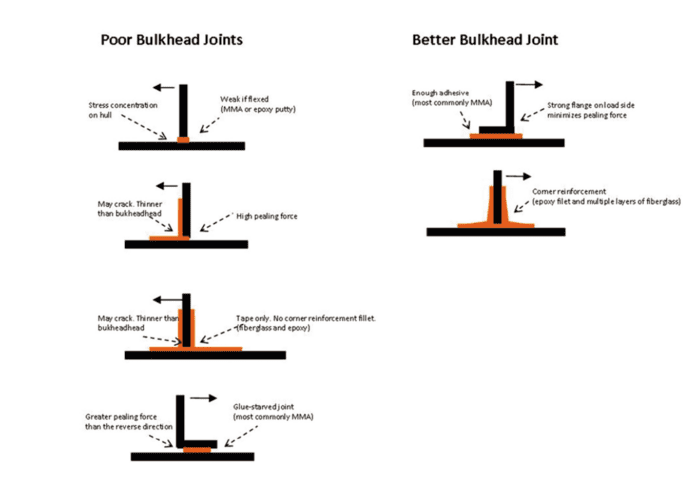

Bulkheads. Most of the bulkhead failures we have seen occurred when a bulkhead was just potted in with MMA or epoxy, with no flange or taping to provide stress distribution.

CONCLUSION

Every joint has a best adhesive or fastener, and one size will never fit all. You will need sealants, flexible adhesives, stiff adhesives, and mechanical fasteners, and to know when to mix and match.