Our long-term testing at Practical Sailor may have the initial appeal of a tortoise race, but things do heat up at the finish line. The following conclusions stem from a decades, and in some cases, an even longer period of observation. In this round of field test feedback, I focus on hardware, cordage, fabrics and coatings plus two pieces of essential equipment that have kept my Ericson 41 Wind Shadow ready for sea as she enters her 50th year.

Fabric Feedback

Fabrics used for sail covers, awnings, dodgers, and biminis face an onslaught of environmental assault. The suns rays deliver both ultra violet and heat energy that work to degrade synthetic and organic fibers. During hot damp summers, these fabrics can behave like a petri dish nurturing mold, mildew, and a whole host of microbial wonders.

A weak chlorine solution lays waste to the biota but with repeated use weakens fabrics already under assault from oxidation and chemical distress from acid rain and atmospheric deposition from inconsiderate seagulls and aircraft flight patterns. In our testing, we were astounded by the durability of some fabrics and the rapid deterioration of others.

Kudos go to Sunbrella and Weather Max for their cover, dodger, bimini fabrics. In 2011, I began a long-term head-to head test, pitting Sunbrella and Weathermax against a wide range of other fabrics (see Functional Fabrics, PS December 2011). Six years later, it is clear that these products are a cut above the rest. For my punishing long term, year round 24/7 test cycle, I fabricated a simple dodger top section and set it up partially under the framework that secured four solar panels. The goal was to see how the totally exposed section and the sheltered segment compared. Eight years later, there were no tears or holes anywhere, the color was consistent, and even an annual cleaning using commercial-grade mildew cleaners did not seem to impact longevity.

One of the Weather Max fabric tests during the same period involved controlled exposure to the elements. I sewed up a teak table cover and left it outside. The only respite from sunshine and atmospheric deposition the table earned was when it was covered by a foot or two of snow. When stitching up the cover, I found the material stiffer than Sunbrella and just a little bit more tricky to sew. But the final test proved its resilience.

While setting up an LPU painting project using the spray gun, I had placed a big piece of cardboard on a teak table Id covered with Weather-Max. I was using the table as a workbench to carry out a precise two-part, LPU paint mixing and straining. Cutting to the chase, the paint cup capsized and the blood red contents flowed over the cardboard onto the Weather Max cover. I grabbed a roll of paper towels and a threadbare beach towel. The desperate sponging resulted in a red and blue abstract canvas-sort of a Jackson Pollack effect.

As a last ditch effort, I donned my mask, goggles, and heavy-duty gloves, uncapped the MEK based spray reducer, and poured it over the table art. To my surprise and relief, I was able to squeegee and blot all of the offending red LPU paint from surface, returning the cover to its Caribbean hue. All evidence of the catastrophe was bagged and a look under the cover revealed no sign of any red paint on the teak or underside of the cover! Weather Maxs impressive chemical resistance was a pleasant surprise, to say the least.

Sadly, the materials used to house essential safety equipment such as the Lifesling and Dan Buoy on Wind Shadow have much less UV and environmental resistance. They silently degrade as the safety gear hangs on the stern pulpit. These MOB recovery devices arent cheap, but if you keep them at the ready as you should, you cut several years off of their lifespan.

Some crews remove the gear and stow them in a cockpit locker when they are away from the boat. Others fabricate a Sunbrella/Weather Max cover that can be quickly snapped or secured with Velcro over the rail-mounted gear. Its essential that these covers be easy to remove prior to setting sail.

Practical Sailors concern is that people will simply not buy this equipment, knowing it will fall to pieces in short order. That would be a terrible shame since these MOB devices are important safety aids and it would be a relatively small cost to manufacturers to use more UV stable material that would greatly extend the lifespan of the product.

El Dorado in a Can

One year away from the half-century mark Wind Shadow is again going through another DIY paint and varnish makeover. This is the third time her hull and deck have been under the gun-spray gun that is. During the four plus years weve have owned the sloop, weve learned a lot about what works and what doesn’t when it comes to paint varnish and other finishes.

Gelcoat gradually loses its luster and wears thin from wet sanding, compounding and years of buffing away accumulated oxidation. Wind Shadows gel coat endured 12 years of heavy-duty use, including a five-year voyage around the world. Im a big fan of epoxy primers and two-part LPU topcoat material for above the waterline use. The process begins with good prep work and a clean, dry, 80-grit sanded, filled and faired, FRP surface.

If the gel coat is well adhered to the laminate, overcoating with epoxy primer works, but if the substrate is badly crazed and the edges are lifting, it is time to shoulder the arduous task of sanding away offending gel coat, fairing with epoxy, priming and carefully executing this prep phase of the paint makeover. A stable substrate adds up to big benefits in the long run. (See Careful Application Saves Your Sanding Arm, PS July 2016.)

I give high marks to Interlux 404/414 primer (Epoxy Primekote) and a double thumbs up to Awl Grips 545 primer. They both have superb adhesive qualities and act as an ideal tie coat between the FRP laminate (or gelcoat) and the single or two-part paint.

When it comes to spraying, rolling, or brushing on a final coats, the products that have held up best in various tests and projects Ive carried out are Awlgrips Polyester LPU, Interlux Perfection, and Epifanes Two-Part finish. After a decade, these paints were still uniformly adhered, but they were dull and oxidized. The good news is that the primer remained intact, and after sanding with 220-320 grit sand paper, masking, and a wipe down, the surface was ready for recoating. The added challenge of using a two-part paint is worth the trouble, in my view. However, there are single-part options for those who prefer an simpler application. (See Topside Paint Three-Year Endurance Test, PS December 2012 online.)

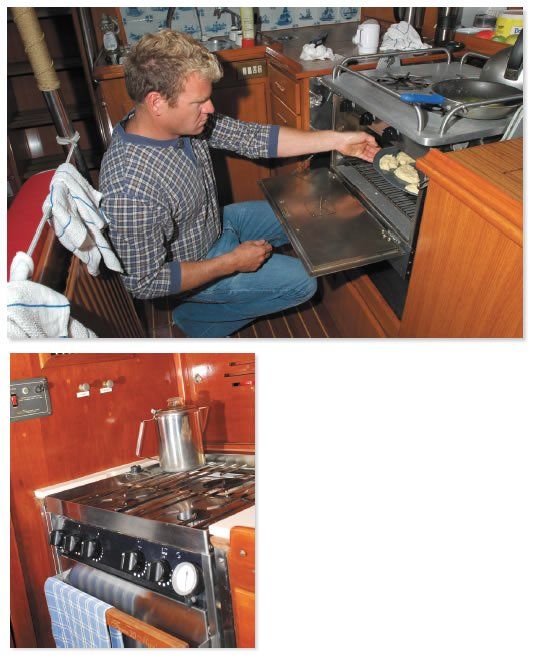

Cuisine in Motion

When looking over a cabin full of gear it is hard to pick a favorite. Initially, we turned to the nav station and homed in on the latest MFD-a digital clearing house for electronic information. But those like me who have voyaged far and wide in the dark ages, when a compass, depth sounder and sextant held sway, know that theres an even more vital piece of cabin bound equipment. The title indispensable must be given to the ever-ready galley stove.

With the pressurized alcohol fuel nightmare astern, and LPGs domination over CNG, the evolving era of Shipmate, Dickinson and Paul Luke (Heritage) stoves have given new credence to cooking aboard. Strangely, I still tend to associate the gales Ive encountered at sea with the aroma of ship-baked bread. A cold and hungry crew develops an affinity for what the cook can do with his or her priceless galley stove.

Heat generation might be the first job of a good galley stove, but aboard a monohull, the stoves ability to tame stove-top gyrations is what distinguishes the good, the bad, and the ugly in the world of marine stoves. As one old salt put it, a bright flame and a hot burner are of no use at all if the cook pot and dinner are on the cabin sole.

Theres a science to effective stove gimballing that involves pivot point location and stove ballasting. The addition of effective pot clamps and perimeter rails also help trap the evenings meal.

Today, Force 10 holds market share with a line-up of stoves that work well at sea or at anchor. But its important to read the stove manual and make sure the builder has bent the small retaining tabs on the bracket that keep the stove in place. Although the stove manufacturers insist these tabs are adequate to keep the stove in place, you can also build a more secure bracket (see Bulletproof Bracket, PS July 2007.

In several cases we know of a serious knockdown has caused the galley stove to jump off its gimbals and injure a crew member. Incidentally, multihulls are not immune to this risk.

Marine Metal

Silicon bronze once held top dog status as a marine metal ideally suited for turnbuckles, toggles, through-hull fittings, fasteners, and shelves full of other useful deck hardware. Unplated, it developed a pale green protective layer-a metal in aesthetic harmony with gray teak decks and varnished spruce spars. The alloys self-lubricating nature kept the threads of turnbuckles easy to tighten or loosen without the risk of galling. Fastener treads did not freeze together due to minor oxidation.

Its true that not all bronze alloys are the same. But the alloys chosen by Wilcox Crittenden (now owned by Thetford), Merriman Perko and other well-respected domestic hardware manufacturers have stood the test of time. The value found in cast, forged, and machined silicon bronze hardware comes from a well-balanced compromise that blends tensile strength, malleability, ductility, and corrosion resistance.

For over a decade we have monitored a specific selection of silicon bronze turnbuckles, thru-hulls and winch drums and found them the closest thing to a no-maintenance material one might encounter aboard a sailboat. This is especially appreciated when it comes to submerged hardware and keel bolts.

Stainless steel, todays centerfold metal, is another marine material that comes in a wide array of allows. Most have an unfortunate tendency to become more galvanically active when submerged. Its high galvanic nobility plunges when immersed in sea water, and this increases its tendency toward crevice corrosion making it less than ideal as the hardware of choice for submerged use.

Another big plus linked to silicon bronze is its ability to put up with shape distorting bends, out-of-round holes and other effects of stress that warn a boat owner that its time to replace the hardware.

So, the bottom line for a DIY sailor who is re-rigging or adding hardware above or below the waterline, is to recognize that silicon bronze may still be your best bet. Its not quite as strong as stainless steel of the same dimensions, but a small increase in size will solve that issue. And of equal importance, as time goes by, the longevity battle in the marine environment is owned by silicon bronze. If you must have hardware thats as shiny as a handsome Rolex watch case, you can always opt for chrome-plated silicone bronze.

A good line

Cordage is creeping up in price but the line available today is better than ever. New fibers not only promise better performance, they deliver. Its true that a cruising sailor can still get along with nylon three-strand or braided anchor rode and Dacron (polyester) sheets and halyards, but performance-oriented sailors have discovered better ways to lessen stretch and have flocked to higher modulus fibers. Thanks to effective fiber coatings and urethane-based UV blockers, contemporary cordage stands up to the elements. In our testing, it has endured a decades worth of sailing loads, UV assault and chafe from numerous sources.

Novabraids XLE, a traditional double braided polyester rope, endured long-term sun exposure and winch-jaw friction with only minimal cover degradation. Year after year it retained its suppleness, held bowlines tightly and was slow to show its age. New England Ropes Sta-Set X, a polyester product with longitudinal fibers in the core, is less stretchy and proved to be good halyard on cruising boats with roller furling headsails that require less extreme halyard tension. Racers seeking more luff tension will find the investment in higher modulus core fibers such as NE Ropes V-100 money well spent. When it comes to a mainsail halyard, we also prefer a higher modulus, less stretchy core fiber and polyester cover.

One of our favorite high modulus lines was Samsons single-braid 12-strand Dyneema Amsteel. Its a special purpose cordage that we found dozens of uses for thanks to the ropes suppleness, extreme lack of stretch and high strength. It worked well when used as a storm sail tack pennant, a temporary bob stay on a sprit pole, and to lash blocks to deck hardware. Its also ideal in damage control situations such as jury rigging.

In one of our field tests, we used a piece of 3/16-inch Amsteel as a downhaul on a windsurfer sail. Line used in this context puts a pre-bend into a stiff carbon spar, must endure significant surge loads, plus continuous chafe over metal parts. Prior to switching to the single braid Amsteel, the down-haul line never lasted a full season. Now, after three years of punishing use, the only apparent deterioration is some minor chafe where the rope rides on the sails tack fitting.

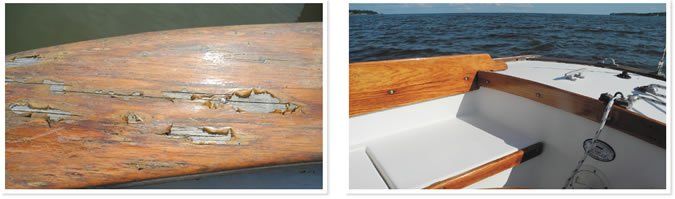

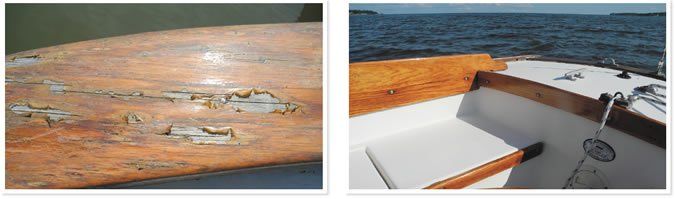

Brightwork

Wood trim on sailboat topsides has earned a spot on the endangered species list, and many celebrate its move toward extinction. However, like many, I still appreciate the aesthetics of exterior wood. Fortunately, there are products that make brightwork easier or the effects longer lasting-but not both.

Wood is an organic material and is eager to rot when not protected with a well-adhered coating. Yes, teak and its cousins are less prone to such deterioration, but uncoated teak continues to oxidize and seams and glue joints dry out and crack. So, deck woodwork needs to be protected by sealing, varnishing or painting. Sealers range from thin penetrating compounds to soft surface coatings and are quick to apply, easy to sand and in need of more frequent recoating than harder varnish type materials.

Based on PS tests and our own experience, we find Cetol to be a practical finish for those who don’t have time or gusto for conventional varnishes.

Cetol is softer than traditional tung oil spar varnish, but it lays on thicker and is less likely to hang. This means that fewer coats are necessary and prep work is less exacting. There is a choice of natural or pigmented coating, as well as a gloss overcoat.

After a few seasons (2 to 3, depending on the climate), the warm glow can become a dull brown residue, and the surface needs to be scraped or sanded clean. The good news is that Cetol is soft, and compared to scraping away a two-part varnish, or even single part varnish, the chore is more pleasure than pain.

Epifanes Wood Finish is another of our favorites, its a tung oil and phenolic resin based coating that does not require sanding between coats. It can be very useful in the varnish build-up process and is a good choice when it comes to finishing spruce spars, oars, exterior mahogany trim and teak rails.

Each painter becomes familiar with specific products and often discovers small application nuances that improve the finish work. I like Interluxs Schooner Gold because of its blend of application ease and good longevity attributes. Ive recently begun using Awl Grips Awlwood exterior clear system. Relatively new, it features a special tinted primer and clear acrylic gloss. Initial results are promising, and down the road Ill have an update on the products durability and longevity.

Hatching plans

Keeping the water out is part of yacht design 101, and deck leaks linked to poor hatch design and construction are high on the list of water tortures. Early on, wooden hatch boxes and lids led water on deck onto sponge-like berth cushions, dampening more than the spirits of the crew.

Attempting to track down leaks was a daunting quest as every corner joint seemed suspect. Replacing Wind Shadow classic teak and acrylic hatches twenty-five years ago with Bomar cast aluminum hatches, was a reprieve from water torture. The rigid frame and reinforced hatch lid resist deformation and the hatch dogs effectively seal the two surfaces. Two of the Bomar hatches are anodized and one is powder coated, the latter finish has held up the best, but all of these hatches get top marks.

Voyager, writer and educator, PS Tech Editor Ralph Naranjo is the former Vanderstar Chair at the U.S Naval Academy. His book The Art of Seamanship, is available at the Practical Sailor online bookstore (www.practical-sailor.com/books).

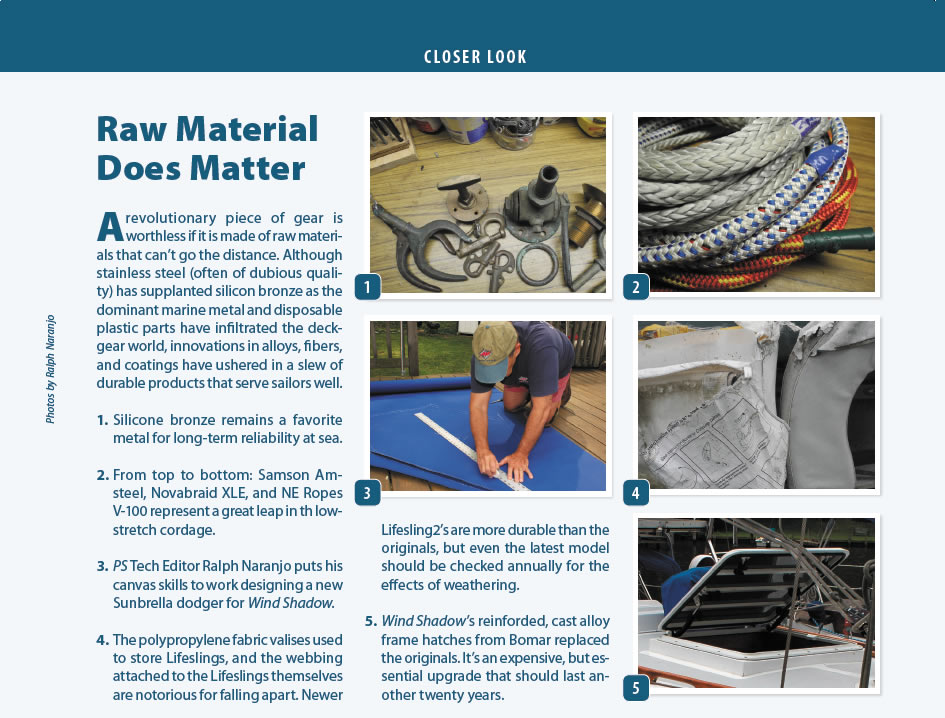

A revolutionary piece of gear is worthless if it is made of raw materials that can’t go the distance. Although stainless steel (often of dubious quality) has supplanted silicon bronze as the dominant marine metal and disposable plastic parts have infiltrated the deck-gear world, innovations in alloys, fibers, and coatings have ushered in a slew of durable products that serve sailors well.

- Silicone bronze remains a favorite metal for long-term reliability at sea.

- From top to bottom: Samson Amsteel, Novabraid XLE, and NE Ropes V-100 represent a great leap in th low-stretch cordage.

- PS Tech Editor Ralph Naranjo puts his canvas skills to work designing a new Sunbrella dodger for Wind Shadow.

- The polypropylene fabric valises used to store Lifeslings, and the webbing attached to the Lifeslings themselves are notorious for falling apart. Newer Lifesling2’s are more durable than the originals, but even the latest model should be checked annually for the effects of weathering.

- Wind Shadow‘s reinforded, cast alloy frame hatches from Bomar replaced the originals. It’s an expensive, but essential upgrade that should last another twenty years.