We now have permanent research satellites in orbit whose sole function is to monitor and study global lightning activity. Like so many areas of science, however, the more we know about lightning, the more we learn what we do not know. For example, while we now acknowledge that “ball lightning” exists, there is still no consensus on how it arises. Similarly, we have discovered, but cannot yet explain, phenomena such as “volcanic lightning” and “superbolts”—which fundamentally challenge all our prior assumptions, because these occur in winter, mostly over oceans, often in Europe.

We do know a lot more about conventional lightning, however, which includes intra-cloud and inter-cloud activity—jointly called “cloud flashes.” The larger inter-cloud strikes are referred to as a “megflash,” the record for which is an astonishing 515 miles (829 kilometers).

Of direct relevance to sailors, however, is cloud-to-ground (often abbreviated to a “CG”) activity. To answer the age-old question as to whether the strike goes up or down, we now know that both types occur. As we were taught in school, the more common is when a storm cloud has negative ions and the ground is positive, known as a “negative CG” event. The alternative, less common but more powerful (by a factor of X10), event is known as a “positive CG,” which lasts longer and looks brighter and more solid—with no branches.

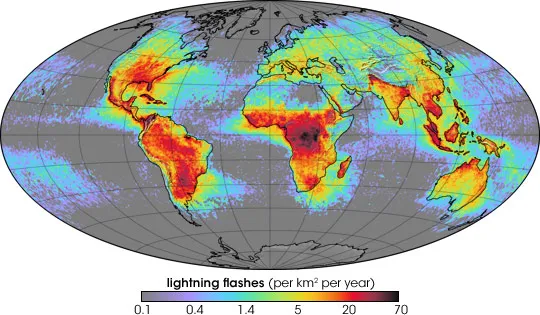

Overall, lightning events occur across the globe at a rate of 50 to 100 times pers second. As the attached NASA satellite image shows (Exhibit 1), the areas of highest concentration are Central Africa, South & Central America, Southeast Asia and the Southeast of the U.S. Most occur in summer, over land, as the land heats up quicker than water. The cruising grounds most at risk are the Caribbean, Florida, the Chesapeake Bay, Panama and Southeast Asia.

Lightning Over Water

While over 90 percent of lightning occurs over land, some research suggests that lightning strikes at sea can be more intense, due to the conductivity of seawater. The dangers arise in five ways.

Most obviously, a ground strike reaches the highest part of the boat (such as a mast) and in seeking a path to ground (the ocean) sends a surge of uncontrolled current through the vessel.

Secondly, side flashes occur when the various conductive components of the boat are at significantly different voltage levels, leading to an electrical charge jumping from one to the other.

Thirdly, side strikes can occur from the boat interior, through the hull, to the water (such as from the anchor locker).

Fourthly, we have the possibility of electro-magnetic (EMP type) induced surge currents, in circuits that were not directly part of any primary or side strikes.

Lastly, we have ground strikes that miss the boat but energize the nearby water, potentially fatal for anything on or in contact with the surface water (estimates vary as to the radius of highest risk but this is sometimes quoted as extending as far as 100 to 300 feet (33 to 100 m).

Can We Prevent a Lightning Strike?

As explained in “Lightning Protection – The Truth About Dissipators,” dissipators work well on a small scale, like discharging static electricity in climate controlled, electronic manufacturing facilities. They work by conveying the voltage level of a ground system to a series of sharp points made of a conductive material, thereby creating ions in the air, reducing the voltage difference, with the intention of reducing or eliminating the possibility of a static discharge.

In the real world, however, lightning can supply a charge far faster than any set of discharge points can create ions (the article calculated by a ratio of at least 4,000:1), which means that these provide little or no protection. There are some major marine equipment manufacturers that continue to market and advocate for such dissipators, however, which is one of several reasons why the ABYC has been somewhat stuck in the last decade or so as to an appropriate lightning protection code.

Nigel Calder has expressed skepticism of such devices, a view I would support. To me, the only viable means of prevention remains being very close to a far larger sailboat (something they may not welcome!) or, more practically, paying close attention to weather forecasts.

Forecasting

If you are marina-based and an occasional weekend sailor, the obvious conclusion is to follow local weather reports and stay off the water if there is any forecast of thunderstorms. But what to do if you are already at sea, perhaps on an extended passage?

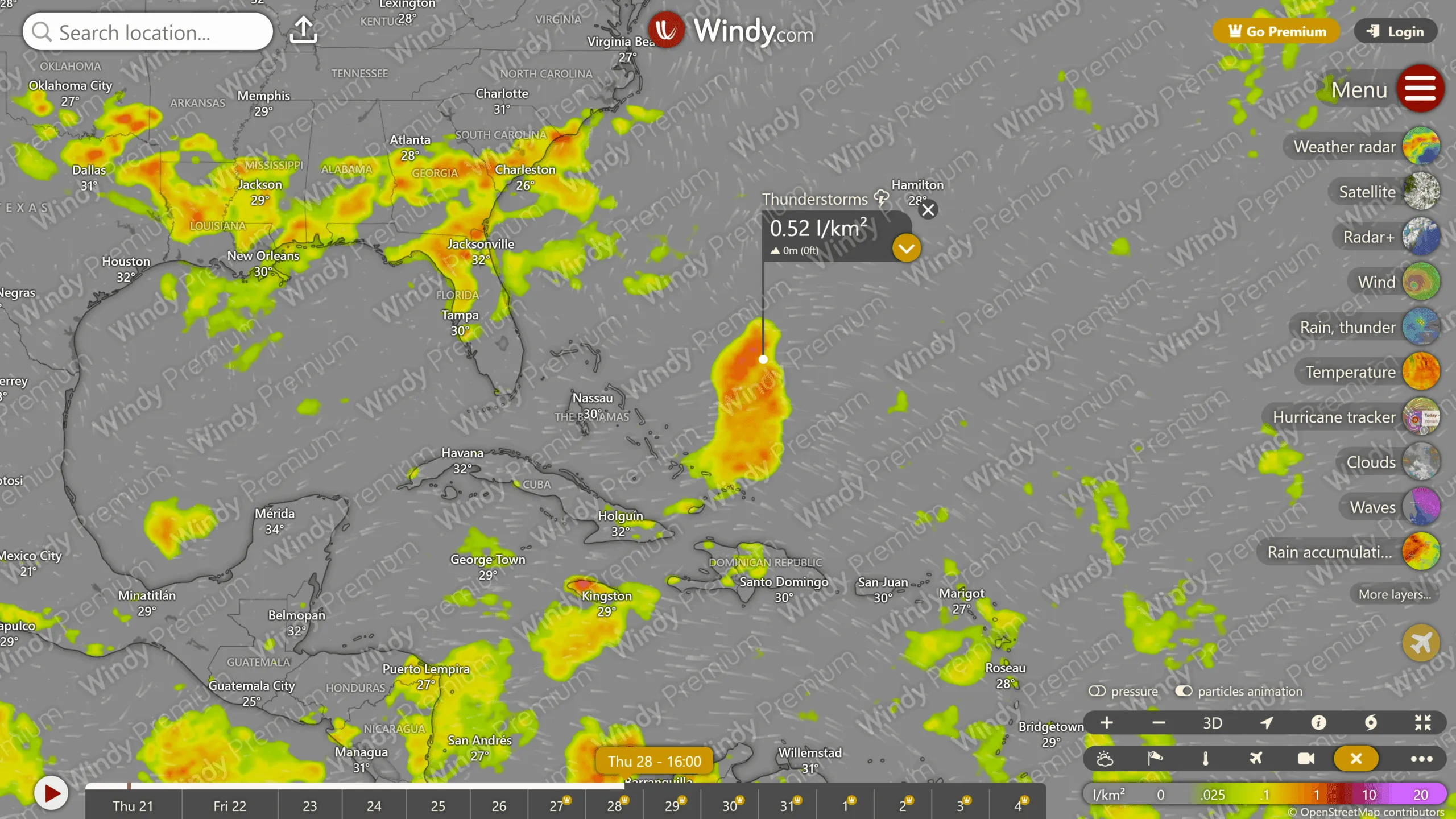

In recent years, weather forecasting apps, such as Windy and Predict Wind, that format ECMWF (European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts) data have begun providing lightning forecasts. As illustrated in exhibit 2, within Windy’s drop-down menu there is a category for “Thunderstorms” color coded for intensity, which uses a unit of forecast “lightning flashes per square kilometer (Km2)”, or approximately 0.36 square miles per day. Thus, you can conduct route planning for thunderstorm avoidance in much the same way as you might factor in more familiar variables, such as wave height or maximum wind gust.

For example, in Central America, where lightning is hard to avoid for months at a time, some cruisers commit to never route through a high risk area, such as 5 flashes per km2 per day (which would be a rate of around one strike every 3 minutes in a 10 x 10 km or 6 x 6 mile area). Of course, a forecast in a lightning prone area, does not guarantee safety but this is a huge improvement in understanding times and areas to avoid. Elsewhere, you would probably choose to adopt a threshold closer to zero.

Reference Documents and Standards

For those that wish to study the matter, there are three key reference documents. A 1992 University of Florida research paper “Boating – Lightning Protection” is somewhat of a foundational document. More currently, there is the 2023 version of The National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 780 “Standard for the Installation of Lightning Protection Systems” in Chapter 10 Protection for Watercraft, and there is the 2006 ABYC standard TE-4 “Lightning Protection.” Beware, firstly, that there is a lack of consensus, as to whether the standards should solely focus on protection of personnel or also address the protection of equipment—damage to which, of course, can be equally life threatening.

There is also some debate as to what works and what does not (such as dissipaters) and, crucially, it is reported that there are sensitivities within the industry e.g. while insurers seek some sort of standard, boat builders are concerned with the potential legal liabilities that might arise from such a standard, especially given that these can be fatal events. The ABYC last published a standard in 2006 (as E-4) but later withdrew it, republishing it as a simple “Technical Information Report.” The NFPA does not seem to be so constrained, however, and has continued to progressively update its standards, as experience unfolds, with 2023 the current published document and a 2026 version already under development.

University of Florida Research Paper

The University of Florida research paper starts with the example of large steel commercial vessels and notes that while these are frequently struck by lightning, their large area of conductive steel—not only in the hull, but in all areas of its construction—allows good passage of the charge from the point of the strike, to the hull and from there, to the ocean. Injuries and/or damage, in large commercial vessels, are therefore relatively uncommon.

Smaller, pleasure fiberglass vessels do not have the benefit of such conductivity, however. When lightning strikes a fiberglass boat, therefore, the electric current searches for the best available route to ground, potentially finding such a route through the human body —which is a relatively good conductor—and/or equipment such as engine, through-hulls etc.

The paper’s core argument is in favor of a good lightning protection system, while pointing out that it may, in fact, potentially increase the possibility of the boat being struck. The sole purpose of a protection system is to reduce the risk of injuries and limit damage.

Sailboats versus Open Boats

![Exhibit 3. Diagram of a boat with masts in excess of 50 ft (15 m) above the water. Protection based on lightning strike distance of 100 ft (30 m). Reproduced with permission of NFPA from NFPA 780, Standard for the Installation of Lightning Protection Systems, 2026 edition. Copyright© 2025, National Fire Protection Association. For a full copy of NFPA 780, please go to www.nfpa.org. This [presentation/training] material is not affiliated with nor has it been reviewed or approved by the NFPA.](https://www.practical-sailor.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Proposed-Exhibit-3.-NFPA-illustration.png.webp)

Exhibit 3—courtesy of The National Fire Protection Association—illustrates the concept. An “air terminal” (explored later) provides such a zone of protection, from that terminal to a point at which that circumference—the source of a strike being the center—touches the water. The higher the air terminal, the greater the area within the zone. With recent revisions, the NFPA have further developed that concept, illustrating that a twin-masted vessel, or a combination of mast plus bimini, with two or more such terminals, provides greater protection, thereby resembling building codes for lightning protection systems.

National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 780

The National Fire Protection Association, Lightning Protection Code, suggests a number of ways in which the boater can minimize damage. A system shall consist of:

- One or more “Strike Termination Devices” (such as a mast or bimini) are required (a sufficient number to ensure complete protection of the vessel).

- In the case of a non-metallic mast, an “air terminal”, shall be fitted, a minimum of 10 inches above the top of the mast (such that all masthead fittings are protected).

- Permitted conductive materials are copper, aluminum, stainless steel and bronze.

- Multiple grounding electrodes are required to be installed underwater, on the hull. The “main grounding electrode” shall have a minimum face surface of 1 ft2 but this can be made up of multiple smaller electrodes. Supplemental grounding electrodes are permitted and rudders, struts etc. may serve as such electrodes. Any paint or coating on the electrode cannot exceed 1mm (0.04 inches). Steel- and aluminum-hulled vessels are exempted from the requirement to fit such grounded electrodes.

- A connection shall be made between the air terminal and the grounding electrode, by means of the “main conductor” of specified size and design. Masts, davits and handrails are permitted to be part of this main conductor system.

- A “loop conductor,” which is a continuous, horizontal, loop, outboard of all crew areas, wiring and electronics. It shall be connected to the main conductor and —through a “bonding conductor”—to the shrouds. All large metallic masses shall be connected to the main conductor or the loop conductor.

- The NFPA code does not address equipment protection and is silent on issues such as lightning arrestors.

ABYC Standards, Chapter TE-4 “Lightning Protection”

The 2006 ABYC TE-4, uses similar language and concepts of a zone of protection, air terminal and what they refer to as “grounding conductors” and “grounding terminals.” It specifies that the air terminal has a minimum 3/8-inch (9.5mm) diameter copper or 1/2-inch (12.7mm) diameter aluminum rod, extending at least six inches above the top of the mast. The ABYC has not yet adopted the concept of the loop conductor but requires that shrouds be connected to the lightning protection system, in addition to any large metal objects (tanks, engines, winches, etc.) within six feet (1.8 m) of any lightning conductor.

They require the primary conductor to be a near vertical run, with a minimum radius on any bends. As to the grounding terminal, underwater metallic surfaces, such as propellers, rudder etc. can only contribute to the specified 1ft2 surface area, if directly below the mast but may, be part of a supplemental system. TE-4 recognizes that the plate may be in the form of a strip (not that the NFPA excludes this) and there are many professionals that argue that a long grounding strip is a superior way to configure the grounding terminal.

As to the protection of equipment, the standard requires, where possible, that electronic equipment be enclosed in grounded metal cabinets and that in order to protect radio transmitters, antenna feed lines should be protected with lightning arresters.

One surprising inclusion is that the ABYC specifically allows the use of lead (the conductivity of which is a fraction of copper or aluminum), for the grounding terminal. No doubt they are thinking of a lead keel—that surface area would exceed the specified minimum of 1ft2, thereby compensating for the poor conductivity—but the standard does not actually state that. Moreover, lead keels are mostly encapsulated in a polyester resin fiberglass—which is even less conductive—in addition to coatings such as antifouling. For all these reasons I would not consider the lead keel to be a viable ground terminal for my own boat.

When Caught in a Storm

Should you be caught in a storm, the precautions that the University of Florida paper recommends are similar to, but more comprehensive than, those recommended by ABYC:

- Stay in the center of the cabin (if the boat is so designed). If no enclosure or cabin is available, stay low in the boat. Don’t be a “stand-up human” lightning mast!

- Keep arms and legs in the boat. Discontinue fishing, water skiing, scuba diving, swimming or other water activities when weather conditions look threatening.

- Disconnect and do not use or touch the major electronic equipment, including the radio, throughout the duration of the storm.

- Avoid making contact with any portion of the boat connected to the lightning protection system and never touch two such components at the same time.

- Many individuals struck by lightning or exposed to excessive electrical current can be saved with prompt and proper artificial respiration and/or CPR.

- If a boat has been, or is suspected of having been, struck by lightning, check out the electrical system and the compasses to ensure that no damage has occurred.

My Own Preparations

As I sailed down the Mexican coast, heading towards Central America, I become progressively acquainted with the question of lightning risk, from the story’s cruisers heading north would frequently tell. Some stories were truly frightening (a solo sailor knocked unconscious and drifting for several days); other stories included gaping holes in the hull, surrounding what once had been a through-hull but; by far the most common story, was of a full loss of electronics—including engine electronics, in more modern boats.

So, What Preparations Did I Personally Undertake?

Operationally, I disconnect all electronic equipment once I see any sign of lightning on the horizon. I purchased an old-fashioned handheld marine GPS and that, together with all other portable electronics (hand-held VHF, cell phones etc.) are placed into the boat stove oven, which serves as an effective faraday cage.

As the lightning storm is getting closer, I place myself and crew in what I believe is the least hazardous location (sitting down below, not in contact with any grounded component). Standing on the bow, or sitting in a dinghy, risks placing one well outside the zone of protection (assuming that you have one) and any operations such as anchoring or foresail changes need to be completed well before a lightning storm approaches.

I also bought a second, simple, depth sounder, independent from the primary, integrated system, with the reasoning that if I were ever to lose my prime electronics, I would still have basic depth information available.

The next simple step was to add a surge arrestor to the main coax VHF antenna cable. I question whether such a simple device can really interrupt a lightning surge current, but they are small, inexpensive and have no impact on VHF operations, so there is little to lose and much to gain by installing one.

More Boat Rewiring

The next step, however, was the more time-consuming measure. Once I began studying lightning, I resolved to replace the original bonding system, electrically tying all significant metal components together, as the ABYC code recommends: wind vane, stern handrail, dodger, steering, bimini, lifelines, bow rail, engine and the mast. Nigel Calder calls this an “equipotential bonding system” or “internal lightning protection.” Had I read the NFPA standard before I undertook that wiring exercise, I would have wired this as a loop, as that document recommends, and I might yet reconfigure the wiring that way.

But What About Ground Terminals?

After a lot of thought, what I resolved to do was to through-bolt four 8.1/2-inch x 4.1/4-inch (215 mm x 110 mm) commercially available aluminum anodes—sourced via Amazon or elsewhere—to the underside of the hull, one close to the engine, two directly under the mast and one further forward. It may not be a perfect solution, but I believe I am now better prepared than most fiberglass boats on the water.

Conclusion

To take the most obvious type of incident, a strike on the mast will first hit that air terminal, travel in an almost perfect vertical line (as the ABYC suggests) through the mast, with large cable connections between the mast to the two anodes directly beneath. Separately, both the wind vane and bimini would act as a strike termination device, with its own a good electrical path direct to the rear electrode, so in many ways I anticipated the NFPA standard without having read it at that time.

With all major metallic components at the same potential, the risk of side flashes is minimized. So, yes, the system could be improved with more metal in the water, but one also has to be practical. Hopefully I will never get to test it.

We have been caught in scary lightning storms off of Tampa twice now. I have thought of getting heavy duty jumper cables and clamping them to the shrouds, dumping in to the water. If done at beginning of the scare, do you think that would improve safety?

Yes, every little bit helps, although I understand that the shrouds are rarely the main path for lightning. I know of others that have improvised, when caught out, by wrapping anchor chain around the mast and dangling the chain in the water (both sides). That too might theoretically help a little but, as the article explains, such measures are not providing a straight path (from mast to water) and side strikes would remain a serious possibility. The better solution is a more comprehensive solution, as the NFPA talks us through.

We all know that cats get struck far more often than monos. Of course there is no way to make a direct vertical path to water from the cat mast step. Any research or even any cogent thoughts on this dilemma?

Maybe thats a good case for the jumper cable approach. It would be a relatively straight run on many cats from the mast down to the water.

There is so little research on small boat lightning strikes (as it is impossible to simulate in the laboratory) leaving only the limited data from the few insurance claims to guide everyone. I can’t see why catamarans should be any more or less likely to be struck but, as you suggest, the issue may be more a question of when hit, what path the strike follows and what damage occurs. While the ABYC focus on the straightest possible path to ground, the NFPA do not have the same focus, which begs the question as to how important that straight path is. If it were me, i would place a metal plate (or strip or large anode) on the inner surfaces of both hulls (closest to the mast) and wire heavy cables from both sides of the mast (and the shrouds) to those. Of course, following the NFPA recommendations in full (multiple terminals and multiple electrodes) would be the more prudent way to proceed.

Thanks for the informative article. Lightning has been a particular interest of mine since my 26’ trimaran was struck in August ‘24 (on a mooring, thankfully no one aboard). The current certainly followed the shrouds and then holed the hull at each chainplate making its way to water. I believe it is likely that if I’d hung jumpers from the shrouds to water it would have prevented the holing of the ama hulls. The total number of holes over the three hulls was sixteen, almost all of them below waterline. The foam core construction, and three foot depth of the mooring kept the boat mostly afloat. If the amas had not been holed it is likely the entire boat would have remained afloat. The largest air gap the current seemed to jump appeared to me to be over six feet long. I fear if anyone had been aboard they would have been seriously injured. I have had the rigging inspected, and have inspected a dyneema halyard inch by inch and can find no damage to either component. The electronics, including the panel, were all destroyed. I am somewhat surprised there was no fire aboard. There was a flagpole that is maybe 20’ taller than the mast about 75 yards from where the boat was moored. At some point someone will explain why all the anecdotal evidence of multihulls being hit more often than monohulls makes sense…maybe increased surface area in the water?