Freedom Yachts were the invention of Garry Hoyt back in the early 1970s. An advertising executive and champion one-design sailor, Hoyt reached a stage in his life when he wanted a cruising boat, but he found the existing fleet ordinary and unsatisfactory. So—the story goes—he set about designing himself a boat. The result was the Freedom 40, an unusual-looking cruiser with a long waterline, conventional hull, and a peculiar wishbone cat-ketch rig.

Hoyt marketed the Freedom 40 with the diligence and success you’d expect of an accomplished advertiser—claiming speed, quality, and simplicity of handling for his innovative-looking boats. In time he designed (often with the aid of professional naval architects like Halsey Herreshoff) and sold a whole line of Freedoms—a 21, 25, 28, 32, 33, and 44, as well as the original 40.

At the time, Hoyt’s company was unusual—because Freedom Yachts was a “boatbuilder” that didn’t build the boats. Instead, Hoyt went to Everett Pearson, pioneer in the fiberglass boatbuilding industry and one of the founders of Pearson Yachts.

Tillotson-Pearson took on the Freedom line, establishing a reputation for Freedom yachts as topend, high-quality production boats. Ultimately, Hoyt sold the company to Tillotson-Pearson.

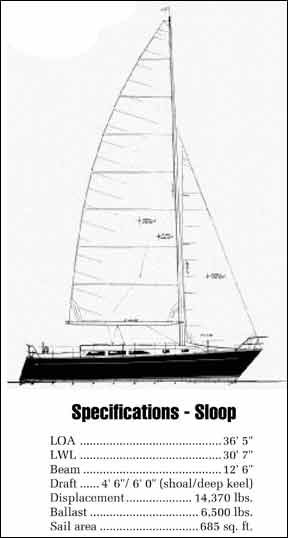

One of the first moves of the new owners was to revamp the Freedom line. The company commissioned new designs from California-based naval architect Gary Mull, well known for his race boats and his wholesome racer/cruiser designs like the Ranger 29 and Ranger 33 in the early 1970s. The Freedom 36 was the first of the Mull designs, and it was followed by a 30, a 28, and a 42. The 36 went out of production in 1989.

The Mull-designed Freedoms share a profile that is rather different from the older Freedoms—with fewer curves and more sharp turns, most noticeable in the square, boxy cabinhouse that is remarkably reminiscent of a Ranger 26. The boats are generally plain and simple looking, with virtually no exterior wood trim.

The most noticeable characteristic of the line continues to be the unstayed carbon fiber mast that had become a hallmark of all the Freedom boats. Most traditional sailors would describe the new designs as big catboats, with the enormous-diameter mast set well forward, but they do carry a vestigial jib and are technically sloops. All the new Freedoms are rigged with the aim of simple handling that has always been associated with the line.

The Mull boats have also maintained the general concept of enormous beam and long waterline with almost no overhangs, and the boats have more interior volume for their length than almost anything else on the market. The major difference from the older boats is that the hull underbodies are thoroughly modern in the Mull designs, with flat bottoms, fin keels, and spade rudders.

Hoyt originally tried to market the Freedoms directly to customers, but the company has since developed a widespread network of dealers which generally have a good reputation for servicing the boats they sell. The company has also developed a good reputation for responding to warranty problems and other customer complaints.

For example, the Freedom 36 that we sailed for this evaluation had originally been sold to an owner on the west coast, and had developed some gelcoat problems on the deck. The company eventually replaced the boat with a new one—an incredibly rare occurrence among boatbuilders—had redone the deck completely, and then re-sold the boat to the current owner at a reduced cost.

Similarly, while we were evaluating the 36, the owner received a package from the company with a kit to modify the lightning protection system in the boat. The new boats were being set up differently, and the builder thought the change was advisable for all boats. They provided retrofit kits—at no charge. On its latest boats, the company is also offering a 10-year warranty on the hull—even against gelcoat blisters—and a lifetime warranty on the spar to the first owner.

While there has never been a boat line with no problems, buyers of Freedoms should have better expectations than most of successful dealings with the company.

Hull And Deck

Both the hull and deck of the Freedom 36 are fiberglass with a Contourkore balsa core throughout. There are potential problems with water absorption in both hull and deck of balsa cored laminates, with little way for the owner to guard against it except by depending on the integrity of the manufacturer. Tillotson-Pearson is one of the few companies that we would count on to produce a good, long-lasting hull in boat after boat. Basic construction is solid.

The fiberglass itself is a laminate of E-glass mat and stitched unidirectional fiberglass, with vinylester barrier resins in the exterior layer of the hull below the waterline. The outside layer is an isophthalic gelcoat. Both the vinylester and the isophtalic resins are believed to provide the best protection against water absorption and blistering. This is a high-cost fabrication, but Freedom obviously has faith in it.

One of the big advantages of balsa coring is the thermal and acoustic insulation it provides. Condensation problems inside the hull are greatly reduced, and the hull has a solid, quiet feel to it going through waves.

The drawback of balsa coring is that one must exercise more care than normal when installing through-hull and through-deck fittings, for example being careful not to compress the whole laminate and allow for penetration of water. Cracks or other damage to the hull must be attended to promptly.

The hull and deck are laid up separately and joined with an inward-turning flange on the hull on which the deck molding sets. An adhesive caulk, 3M-5200, is laid in the seam, and the joint is through-bolted with 1/4″ stainless bolts through an external aluminum toerail.

We examined a number of hulls and found them generally fair, with no obvious problems. Exterior gelcoat work is generally good.

Two keels are available—either a deep fin or a shoal draft fin. The 36 we sailed had the deep fin, which is an external lead casting, bolted to the hull. The shoal keel is encapsulated in a keel cavity and fiberglassed to the hull. If you can stand the draft, the deeper keel will be preferable in terms of performance as well as construction.

Overall, the construction of the Freedom 36 is high-quality, with everything being done pretty much the way industry standards say they should be done. The single exception we found was not in the 36 but in a Freedom 28 we examined. The 28 had a chintzy plastic through hull fitting for a sink drain, with no seacock—an odd oversight in an otherwise well-built boat.

Rig

The unstayed carbon fiber masts were quite radical when Freedom first used them, but they are well established and proven by now. They are laid up somewhat like fiberglass, with carbon fibers wound around a form and impregnated with resin. For equivalent strength, they are much lighter and stiffer than an aluminum mast.

Under sail, it’s a bit shocking at first to see the mast bend in puffs, especially since it’s so tall (55′ 6″ above the waterline). But once you’re accustomed to that peculiarity, there should be little to worry about in terms of strength or longevity. We were unable to find any statistics or insurance figures on carbon fiber mast failures compared to aluminum mast failures, but we suspect the odds of a dismasting or other significant failure are no more likely—perhaps even less likely—with the carbon fiber than with aluminum. We are aware of at least one mast that was damaged in a lightning strike.

The Freedom 36 was available with both a sloop rig and Freedom’s trademark cat ketch rig.

Handling Under Power

A three-cylinder 27 hp Yanmar diesel is standard. The engine is adequate, though certainly not oversized.

Engine installation is well done, in a small compartment lined with a lead/foam sound deadener. Access to the engine is possible from the front by removing the companionway steps, and from the port cockpit locker by removing a panel. It’s hard to get at the Yanmar’s dipstick on the engine’s starboard side. There is a small screw-out port for access from the aft cabin, but the port is about a foot ahead of the dipstick.

The boat comes with a solid two-bladed prop which most owners will want to trash immediately, replacing it with a folding or feathering prop. The boat we sailed had a three-bladed feathering prop, which not only lets the boat live up to its sailing potential, but also seems to improve backing power. A folding prop would be much cheaper, though motoring performance would not be as good as with the three-bladed feathering prop.

It surprises us that companies which tout the sailing performance of their boats continue to fit them out with solid propellers. There’s almost nothing you can do that will degrade sailing performance more than carry an exposed, solid prop, especially when the wind turns light.

With the three-bladed feathering prop, the Freedom 36 performs well. The boat backs out of a slip, goes where you want it to go in reverse, and powers easily to hull speed without overloading the engine. The engine is mounted slightly off-center so the shaft is at an angle to the centerline of the boat, and some people will tell you that this helps the boat track in a straight line under power. The 36 did track straight, but then most boats with centerline installations track straight, too.

With the deep fin to pivot on and the spade rudder located way aft, the boat turns sharply. The large mast and the high topsides provide plenty of windage, but generally the Freedom 36 should be nimble enough to make handling in close quarters no problem.

Handling Under Sail

“Easy” is the key word in the company’s promotion of their sailboats. We found the mainsail a bit of a nuisance to hoist and lower, with the full-length battens fouling the lazy jacks, but other than that the boat is truly easy to sail.

All the gear is of good quality. Halyards are led aft to the cockpit, through stoppers to self-tailing winches. The jib can actually be hoisted by hand, but the main requires the winch to raise it the last 10′ or so. Other controls (outhaul, reef lines, boom vang, cunningham) also lead to sheet stoppers in the cockpit. A neat feature is the “panel” for hanging the coiled lines, just behind the winches at the front of the cockpit.

The mainsheet is a four-part tackle at mid-boom, running to a Harken traveler ahead of the companionway. Frequently, the mechanical advantage of a mid-boom sheeting arrangement is so low that mainsail trimming is hard, but we found we could handle the mainsheet by hand easily in winds up to about 12 knots. Thereafter, we used the winch. All winches are adequately sized, though self-tailers are an option that almost everyone will want.

The non-overlapping jib uses a sprit that fits in a sleeve on the sail. The jib is self-tacking, with a single sheet that is easily controlled by hand. It is amazing how much speed the dinky little jib adds to the boat. Though the company’s literature talks about sailing under main alone, for performance you need the jib. Though we haven’t sailed a Nonsuch 36 and a Freedom 36 side by side, we suspect the Freedom will be noticeably faster, largely because of the jib.

The pulpit-mounted spinnaker pole and the other spinnaker handling gear (all optional) are remarkable in making the spinnaker easy to hoist, jibe, and lower. Of course, the spinnaker is tiny for a boat of this size—closer to what you’d get on a J-24 than on a conventional 36′ sloop. Using the pole—which is pinned at the center so that it pivots on top of the pulpit—takes some getting used to, but once you figure things out it’s a lot easier than jibing a J-24.

We raced the 36 in two PHRF triangle races to try her performance against more conventional boats. In most respects, we found the boat admirable.

Full crew for the racing was two people, and in terms of performance per amount of energy expended, the boat was a clear winner. It is amazing how getting rid of a big jib lowers the activity required on a sailboat.

We did find that the fully-battened main on the bendy mast required new skills, particularly going to windward. The sail has a very wide “slot” in terms of trim, and does not seem to stall out. We messed with the mainsail almost constantly, first trimming it as we would a conventional main, then dropping or raising the traveler, adjusting sheet tension, cunningham, and so on.

The conventional wisdom concerning the rig is that it will not go to weather: you should foot off for maximum performance. But we found that we could point with most of the fleet, and the boat had a B&G Hornet system which kept telling us that our VMG was highest when we were pinching.

Reaching is the boat’s strong suit—as you would want in a good cruiser—and the boat is a surprising combination of effortlessness and power. Handling, including sail trim, is a piece of cake, even with the spinnaker up.

Running, the boat is a little sluggish, even with the spinnaker. We didn’t test the boat fully, but we suspect that jibing downwind on broad reaches may be faster than running dead down, at least in lighter air.

Whatever the point of sail, the sailor used to conventional rigs will have to do quite a bit of experimenting and relearning to get the most out of the Freedom 36.

In terms of absolute speed, the boat was a bit disappointing to us. We expected a little more than we got out of her long waterline.

Her PHRF rating is 150, comparable to the speed of racer/cruisers of 10 years ago like the C&C 33 and 34, or the Pearson 10M. Our impression is that the boat will sail much faster than those boats on a reach, but quite a bit slower on a beat or a run. Her strongest performance will be in stronger winds rather than light air.

There is not a lot that you can do about the fundamentals of yacht design, but we sort of expected that the boat would outsail a 15-year-old Mull design like the Ranger 33. In fact, it won’t. Of course, any passage on the Freedom will be much easier than on the Ranger, much less demanding, and much less tiring. But it won’t be faster, unless you can always make arrangements for a reach.

Nonetheless, after our experience on the boat, we strongly recommend the Freedom 36 as a sailing machine, with the ease of sailing far outweighing any drawbacks. She is a pleasure under sail.

On Deck

You sail the Freedom 36 almost entirely from the cockpit, and it is big and roomy, with plenty of space to do the minimal chores of sail handling.

The benches are wide and comfortable, long enough to use as outdoor berths. It’s not a T-shaped cockpit—one of the few straight cockpits we’ve seen recently, and we decided we sort of like that. There’s ample room for lounging about, and with a dodger and bimini it would be an excellent cruising cockpit. There’s a propane tank locker, and a cavernous portside locker that will be hard to use well unless you can figure out a way to subdivide it.

Wheel steering is standard. The boat we sailed had an optional oversized wheel that simplified steering from the side decks, but made passage around the wheel difficult.

From the cockpit forward to the mast, the Freedom is wide open. It would be an ideal working platform, though of course there’s little working of the boat to be done except from the cockpit. The nonskid of the decks and cabin top seemed generally mediocre.

From the mast forward, the rig gets in the way of things. With the turret-mounted spinnaker pole, the spinnaker in its storage sock, and the wishbone in the jib, the foredeck is crowded. Anchor handling and docking are complicated by having to step over and around the gear, and we suppose many cruisers will think about not having the spinnaker equipment at all. To us, this congestion on the foredeck seems the one major shortcoming of the Freedom rig. Otherwise, the Freedom has a spacious, comfortable deck.

Belowdecks

As you might expect with the long waterline, short overhangs and wide beam, the area belowdecks is huge. We thought the size, especially the beam, might even be a problem under way, but found that that the boat is stiff enough that you should rarely be tossed about.

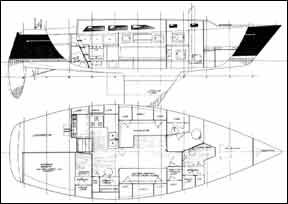

The interior arrangement is fairly ordinary. A big forward cabin has a good V-berth which can be made into a comfortable double by using an insert in the V. There’s a bureau and hanging locker to starboard and a door to the head to port. Headroom is 6′ 1″ near the entry door.

There is good stowage under the V-berth and in a small forepeak—in fact, this boat generally has more storage than is common in more conventional modern designs.

The head is roomy, mostly a fiberglass molding, and has a second door to the main cabin. Opposite the head is another bureau and storage space.

The main cabin is large, with an L-shaped settee around a table which folds up against the forward bulkhead. The table can be folded out so that the starboard settee becomes the outboard seat for an enormous dining table. There is good storage space behind both settees and beneath the port settee. Headroom is a true 6′ 4″.

The galley is U-shaped, with deep sinks, a good dry-storage locker, a gimbaled stove with oven, an adequate icebox, and lots of storage space. A garbage trap in the aft bulkhead lets you drop stuff into a wastebasket stored in the cockpit locker. Now if someone would just come up with some similar way to store your returnable cans and bottles.

Opposite the galley is a navigation table with a swing-out seat. Above the table is the electrical panel, and mounting space for most of the electronics.

The aft cabin, mostly under the starboard cockpit seat, is also good-sized, with a bureau, hanging locker, and decent headroom just inside the door.

Finish below is generally good—lots of teak veneer with a nice contrast in the ash battens used as hull ceiling. The cabin overhead is vinyl panels—OK, but a nuisance if you need to mess with the deck hardware fastenings.

Ventilation is adequate, but would be minimal for offshore passages. You might want to look for the optional dorades to improve air movement below.

Conclusions

In general, we came away from the Freedom 36 with renewed respect for the work of Tillotson-Pearson. For us there’s no question of the quality of construction or general workmanship.

Though high-quality, the Freedoms are plain. If you’re into hand craftsmanship or the sort of excessive teakwork that you find in the best Oriental imports, you probably won’t like the Freedoms, though their belowdecks joinery and finish is very good.

In general, we also like the roominess and livability of the boat. In a 36-footer, it’s hard to imagine more space, or think of a way the space could be better used.

In sailing, the strong point of the boat is ease of handling, and after our trials on the water, we have no reservations about the unusual rig—it works, and it works pretty well. In a 36′ cruiser, we might hope for a little more absolute speed, but the Freedom is no slouch. She will make smart passages, and make them easily.

The major drawback, of course, is price, since the Freedom is on the high end of the price spectrum. With sails and a few “necessary” options like the spinnaker package, self-tailing winches, electronics, and refrigeration, the price of a new boat could easily have topped $110,000.

And if you fully outfitted the boat, including things like customized interior fabrics, you could have quickly gotten the bottom line up to $125,000 or so—a lot of money, even for one of the biggest 36-footers around.

For the price you got a good boat, with assurance of quality construction and a company that will stand behind its products. For many who’ve owned cheap boats, those characteristics will be worth paying for.

Probably the most distinctive thing you’ll be getting in the Freedom 36 is the ease of handling. We can’t imagine how you could get a 36-footer that sails well and make it any easier to handle. A lot of the joy of sailing is making the wind work for you, and the Freedom 36 gives you more return for your labor than any other boat we’ve sailed.

I was surprised to find this article buried in practical sailor. Although written proximately 25 years ago, most of the information rings true today in 2023. The article as you would expect is fair and accurate. My Hoyt designed 32 is long in the tooth but surprisingly with few suggestions that would improve the boat. I’m in my last decade of sailing. Soon someone new will expound on my Freedom’s virtues I’ll leave room for that.