The Henry R. Hinckley & Co.—a name is known to every U.S. sailor, or it should be. It connotes different things to different people, mostly depending on their politics: Down East craftsmanship, big bucks, Yankee work ethic, East Coast blue-blooded snobbery. For those familiar with the company’s work, it more likely means mirror-like varnish, custom stainless steel castings, the trademark dust bin in the cabin sole and “frameless” portlights. Still, critics are quick to complain that other builders produce boats that are just as good for less money. More often than not, these sentiments are just sour grapes from people who can’t afford a Hinckley or even a different brand of comparable quality. While we acknowledge that there probably are a few builders around the world who build boats to the same exacting level, Hinckley is nonetheless unique in North American boatbuilding.

History

Henry R. Hinckley started the company that bears his name on graduation from Cornell University. His first boat, launched in 1934, was a 26-ft. lobster-type powerboat. Soon moving to sail, he designed and built the Sou’wester 34 and 30-ft. Sou’wester Jr. During World War II he built mine yawls, coastal pickets and tugs. While his “production” wooden boats weren’t regarded as anything exceptional, his yard did do some first-class work, building the 73-ft. Windigo (nee Ventura) and Nirvana.

After the war, Hinckley began experimenting with fiberglass as a potential boatbuilding material, though, true to his conservative Maine heritage, he didn’t rush into it. The Hinckley Bermuda 40, introduced in 1959 and in production until the early 1990s, was a watershed for the company.

The Tripp Connection

According to company notes on the B 40, “The firm had built a wooden 38-foot yawl in 1959 and had called her a Sou’wester Sr. It was Henry’s plan to sail the boat hard the coming summer and if she proved her worth, he would use her as a plug from which to build the mold for the first fiberglass Hinckleys. But this was never to occur.”

At the 1959 New York Boat Show, Hinckley was approached by a consortium of eight men, who had commissioned Bill Tripp to modify the Block Island 40 for them. The group’s front man, Gilbert Cigal, persuaded Hinckley to build the boats. The decision to abandon the Sou’wester Sr. was difficult, but from a business point of view, it made more sense to invest in tooling for boats already sold.

The first B 40 was delivered to consortium member Morton Engel in time for that year’s Bermuda Race. Though not completely finished, she finished in the top third of the field. In 1964 she won the Northern Ocean Racing Trophy and the next year the Marblehead to Halifax Race.

Many other B 40s achieved notable accomplishments both racing and cruising. One of the more publicized circumnavigations was done by Sy and Vickie Carkhuff, who wrote about their adventures in numerous magazine articles. It is therefore no surprise that the combination of Hinckley quality and Tripp seaworthiness produced a boat that boasts a 32-year production span.

The company has since transitioned away from sailboat builds to powerboat builds due to market demand.

The Design

Unlike the Block Island 40, the Bermuda 40 is a centerboarder, and a major reason for its continuing appeal. If shoal draft is a requirement, as it often is in some areas of the U.S., one is forced to consider a centerboard design or, when available, a wing keel.

Though not terribly beamy by today’s standards, the B 40’s 11-ft. 9-in. beam is substantial. If you can’t get stability through ballast located deep (remember, the design parameter was for a shoal draft boat; and, fin keel boats weren’t considered suitable in 1960 for offshore work), you must get it from what is called “form stability,” that is, the shape and dimensions of the hull. Similarly, the interior would not be considered very spacious by today’s standards, but in 1960 it had the room of a wooden 50-footer.

Classic Lines

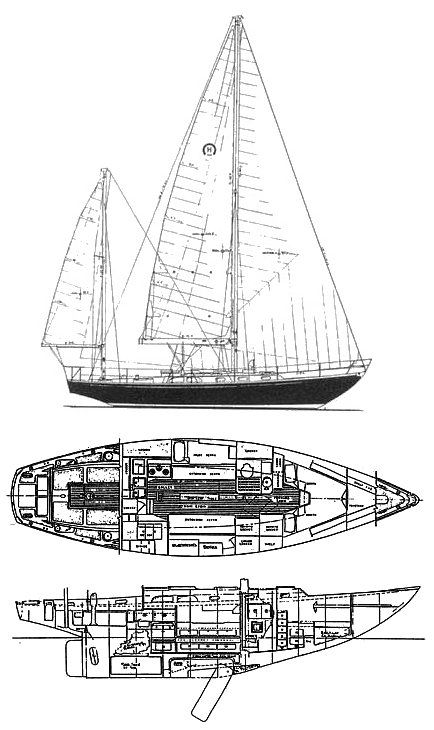

Typical of the CCA (Cruising Club of America) rule, the B 40 has generous overhangs, which contribute greatly to her exceptional looks. The sheer had a nice spring to it, rising just a bit at the stern and considerably more so at the bow. The low point is about two-thirds of the distance aft, helping give the profile its classic lines. Tripp was fond of the concave counter and nearly vertical transom.

The keel draws 4 ft. 1 in. with a gently cutaway forefoot (no “chin”) and straight clean run on the bottom. The rudder, attached to a vertical rudderstock, is hung off the trailing edge of the keel. This is a boat that, should she run aground, won’t suffer a lot of damage, and should give the owner a fighting chance to float her, without crippling the rudder, utilizing their own on-board resources.

Upwind Performance

The downside of this design approach is less than stellar upwind performance. She does not tack as quickly as a boat with a more modern underbody (such as the McCurdy & Rhodes-designed Hinckley 42), and has a tendency to lose speed through the tack until she has a chance to pick up a head of steam.

Then again, the B 40 has a heavier displacement than many modern boats of similar length. The Tripp 40 (designed by Bill Tripp’s son), an all-out racer, displaces 12,750 lb. The shoal keel J/40 displaces 18,650. Full-blown cruisers such as the Tashiba 40 (29,000 lb.) and the Lord Nelson 41 (30,500 lb.) are considerably heavier. So the B 40 is actually of moderate displacement, representing a nice comfortable figure for offshore sailing without forsaking light air performance.

Three Versions

Three different versions have been offered over the years—the Bermuda 40 Custom, the Mark II, and the Mark III. The yawl was the rig of choice until the Mark III, which also is available as a sloop. The Mark II was given an airfoil centerboard and a slightly taller mainmast (49-ft. 3-in. bridge clearance) than the Custom (47-ft. 0-in.). This increased sail area from 725 sq. ft. to 741 sq. ft.

The Mark III was changed further. According to the company’s notes, “In response to the “new” IOR rule, Peter Cooper of Sound Spar conspired with Bill Tripp and Henry once again to raise the aspect of both mizzen and main. This time the main mast was raised a full four feet three inches and moved aft almost two feet. This enlarged the foretriangle to the point where larger primary sheet winches were needed. The additional sail area raised the center of effort, and it was necessary to add a thousand pounds to the boat’s keel. This added weight made her sit lower on her marks and added a foot to her waterline.” Obviously, the company was trying to pump up performance to keep up with consumer expectations.

As one would expect, there have been many other refinements made to the original design, though most are minute compared to the changes in rig and ballast.

The B 40 is built of solid fiberglass—always has been. A “hybrid knit fabric of Kevlar/E-glass” fibers was used in the later-production boats. The deck was originally solid glass. Later it was balsa-cored, and towards the end of production it was cored with 3/4-in. PVC foam, and vacuum-bagged for good bonding of the skins. The hull-deck joint is unusual in that the fairly standard deck-to-hull flange system is incredibly strong. The flange is 1/2-in. thick and about six inches wide, increasing around the chainplates. There also is a lip on the flange that gives the deck a snug fit. In his book, “The World’s Best Sailboats,” Ferenc Máté describes at some length the process of fitting the deck to the hull. The deck is lifted with a chain hoist and lowered onto the hull to determine where the bulkheads should be trimmed. He quotes Bob Hinckley as saying, “We raise it, lower it, raise it, lower it, up and down…until all the tops of the bulkheads fit perfectly.” The two mating surfaces are ground and filled until the two match like a piece of joinerwork. Wet fiberglass mat is laid on the flange and then the two pieces are bolted together. The entire process “takes two days for a small crew.” As implied above, the interior is built before the deck is fastened. It is almost a cliche, but true, that Hinckley built a wooden boat inside a fiberglass hull. No fiberglass is visible. Original buyers could choose any specie of wood they wanted, including cherry, white ash or the traditional Maine white paint and varnished mahogany trim. Whichever they chose, rest assured it turned out gorgeous. Lead ballast is mounted externally, fastened with one-inch stainless steel bolts. The cast bronze centerboard is not operated by a wire pennant but by a worm gear. All deck hardware is through-bolted; holes are not oversized for dropping bolts through but tapped so that each machine screw threads not only into the backing plate and lock nut, but also through the deck itself. Hinckley prides itself on manufacturing as many components as it can, including the stainless steel stem casting, custom tapered mast, steering pedestal, even the stanchions. One could go on and on describing how the through-hulls are countersunk flush with the hull, the number of coats of phenolic tung oil varnish applied to all natural wood surfaces, and how sheet copper is used to bond all sea cocks to the boat’s lightning and bonding system. The engines, of course, are not made by Hinckley, but each is test run for several hours and the standard 55-amp alternator replaced with a 105-amp model to charge the house batteries. A 53-amp alternator charges the engine start battery. The Westerbeke 4-107 diesel was standard for many years, though on later production builds you could also have the Yanmar 4JH2E. Hinckley makes its own shaft log and muffler. Fuel capacity is 48 gallons in a single Monel tank. Three stainless steel water tanks hold 110 gallons. The cockpit seat lockers are gasketed and can be locked from below via a latch in the galley. Lockable, watertight seat lockers should be, but seldom are, a requirement of offshore sailing. Interestingly, Hinckley recommends Marelon ball-valve sea cocks, through-bolted with Monel fasteners (of course, owners could choose whatever they wanted). Of equal interest is the one opening portlight. All others are fixed safety glass, which is preferable to Plexiglas or Lexan in terms of scratch resistance and resistance to ultraviolet rays. The frames are mounted inside, so that they are not visible from the outside. One owner said he wished ventilation was better. Not surprisingly, owners responding to our questionnaire rate construction as excellent—without exception. One reader called his B 40 “bullet proof, over-engineered.” As mentioned under the “Design” section, the B 40 is an adequate performer. She is not particularly fast upwind, due in part to the fat, shallow keel, but does much better off the wind, according to owners. They rate stability as about average, often citing the relatively low 28 percent ballast-to-displacement ratio. One reader said, “It heels early to about 15 degrees, then stiffens.” Another said, “It’s hard to keep the rail in after initial 15- to 20-degree heel (with centerboard down).” On a more positive note, the mizzen sail and centerboard allow the boat to be balanced much better than most designs. One owner said, “On most courses we can almost eliminate weather helm with appropriate sail trim.” Another said balance was “especially good from beam reach to a very broad reach.” These points of sail, for most other boats, cause the most difficulty in handling. Owners rated seaworthiness as excellent. One said he’d taken one knockdown and suffered no damage. Under power there are the usual complaints about losing steering control in reverse, but this is to be expected of a full-keel design with the propeller in an aperture. One reader said, “We sometimes use the centerboard for docking.” The 37-hp. Westerbeke auxiliary, while rated as an excellent engine, has barely sufficient power to punch through headseas. (We have no comparative information on the Yanmar.) Access to the engine, incidentally, was rated as fair. One reader wrote, “All service is from the front end. The sides are accessible through cockpit lockers. You can get right down and sit on the reverse gear if you wish.” Another noted that the shaft and log are “buried,” and difficult to work on. Details of interior layout vary from boat to boat since each B 40 is built to order. The basic plan, however, remains essentially the same. There are V-berths forward which may be converted to a sumptuous double with the addition of the insert board and cushion. The head has a sink and shower as standard equipment, and opposite are a number of cedar-lined lockers for clothes. Stowage space is generous. The standard saloon layout has berths for four: two extension settees, and pilot berths port and starboard. These tend to push the furniture in toward the centerline, making the cabin seem less spacious than more contemporary designs. (This also is partly a function of the B 40’s very wide sidedecks—a blessing on deck and a trade-off below.) While a narrow cabin provides better handholds and is therefore safer at sea, the drop leaf dining table restricts access fore and aft when the starboard leaf is up. That can be annoying. The optional U-shaped dinette eliminates the problem. The galley is aft and is adequate, though compact. There isn’t much counter space other than the lid tops of the icebox and stowage bin. Worse, the navigation station is above the icebox on the starboard side. The optional layout features a navigator’s seat; in the standard layout one must stand. We’d prefer to see a separate nav area with additional room for electronics. For extended cruising, the B 40 is best suited to a couple, with occasional guest crew. For a family with children, the kids would have to sleep in the pilot berths, which is okay but means that their junk will rain down on the settees. Most owners commented on the lack of interior space, but accept it as part of the package, knowing full well that if they’d required more, they could have bought a different boat. The finish detail of the B 40, indeed, any Hinckley, is legendary, and there isn’t space here to describe the many intelligent features that help set this boat apart from the rest of the field. You’ll have to see for yourself, as the interior design and workmanship represent a good part of the total cost. Hinckley takes enormous pride in its work, and offers to its customers a wide range of services. In effect, you become part of the Hinckley family. Most Hinckleys are serviced by the builder, and most used Hinckleys are sold through Hinckley’s own brokerage arm. Because of the substantial investment owners made in purchasing a Hinckley, and because of the continuing support offered by the company, most used Hinckleys are in excellent condition. And the B 40, because of its 32-year production run, may be found with a wide range of options, and can be purchased at a wide range of prices. Resale value is excellent. For example, the base price of a 1975 B 40 was about $90,000. Used models for sale today range from $60,000 to $195,000. Every B 40 is a bit different than the last, so it would be advisable to check several before making a decision. Obviously, Hinckleys aren’t for everyone. They are expensive and only you can decide whether the many little quality details are worth the cost. As one owner said, “The B 40 is to be bought on the day that the full significance of ‘you only have one life to live’ becomes clear.”

Sailboat Specifications Courtesy of Sailboatdata.com

Hull Type: Keel/Cbrd.

Rigging Type: Masthead Yawl

LOA: 40.00 ft / 12.19 m

LWL: 28.83 ft / 8.79 m

S.A. (reported): 681.00 ft² / 63.27 m²

Beam: 11.75 ft / 3.58 m

Displacement: 20,000.00 lb / 9,072 kg

Ballast: 6,500.00 lb / 2,948 kg

Max Draft: 8.60 ft / 2.62 m

Min Draft: 4.30 ft / 1.31 m

Construction: FG

Ballast Type: Lead

First Built: 1971

Builder: Henry R. Hinckley & Co. (USA)

Designer: William Tripp Jr.

S.A. / Displ.: 14.84

Bal. / Displ.: 32.50

Disp: / Len: 372.60

Comfort Ratio: 36.09

Capsize Screening Formula: 1.73

S#: 1.15

Hull Speed: 7.19 kn

Pounds/Inch Immersion: 1,210.40 pounds/inch

I: 49.00 ft / 14.94 m

J: 17.40 ft / 5.30 m

P: 42.40 ft / 12.92 m

E: 12.00 ft / 3.66 m

S.A. Fore: 426.30 ft² / 39.60 m²

S.A. Main: 254.40 ft² / 23.63 m²

S.A. Total (100% Fore + Main Triangles): 680.70 ft² / 63.24 m²

S.A./Displ. (calc.): 14.84

Est. Forestay Length: 52.00 ft / 15.85 m

Construction

Hinckley Details

Performance

Under Power

Interior

Galley and Accommodations

Conclusion

Market Scan Contact

1971 Hinckley Bermuda 40 Hinckley Yacht Brokerage

$142,000 USD (404)328-4560

Southwest Harbor, Maine Yacht World

1970 Hinckley Bermuda 40 Hinckley Yacht Brokerage

$135,000 USD (404)328-4560

Annapolis, Maryland Yacht World

1961 Hinckley Bermuda 40 Engel Volkers Yachting Americas

$59,000 USD 949-835-4876

Saint Simons Island, Georgia Yacht World