Brothers George and Michael McCreary, and Marshall Jones, formed Caliber Yachts Inc. as a backyard boatbuilding company in 1979. No strangers to the sailing world, the brothers grew up racing and cruising Florida and the Caribbean.

Following high school, Mike earned a degree in engineering, with a specialty in naval architecture, from the University of Michigan. He served his apprenticeship on the production line at Gulfstar Yachts, and as a designer for Endeavour Yachts.

George, who managed the business side, received a degree in business administration and marketing from the University of Florida, after which he spent three years working for Morgan Yachts.

Jones began studying the production side of the business immediately following graduation from high school when he went to work at Com-Pac Yachts.

Without bank financing, Caliber Yachts began building boats one at a time, producing its first, a 28-footer, in 1981. By 1985 the company was sufficiently solvent to build a factory, and introduce a 33-footer. A 30, 35, 40, and 47 followed. The Long Range Cruising (LRC) line began in 1994. Caliber Yachts stopped producing boats in 2010.

George, who acted as company spokesman, said the construction and design of the LRC is similar to earlier models. The primary difference is expanded tankage for fuel and water.

The Caliber 40 LRC has a projected cruising range of 1,484 miles when motoring at 7 knots with a Yanmar 50 diesel running at 2,500 rpm.

Design

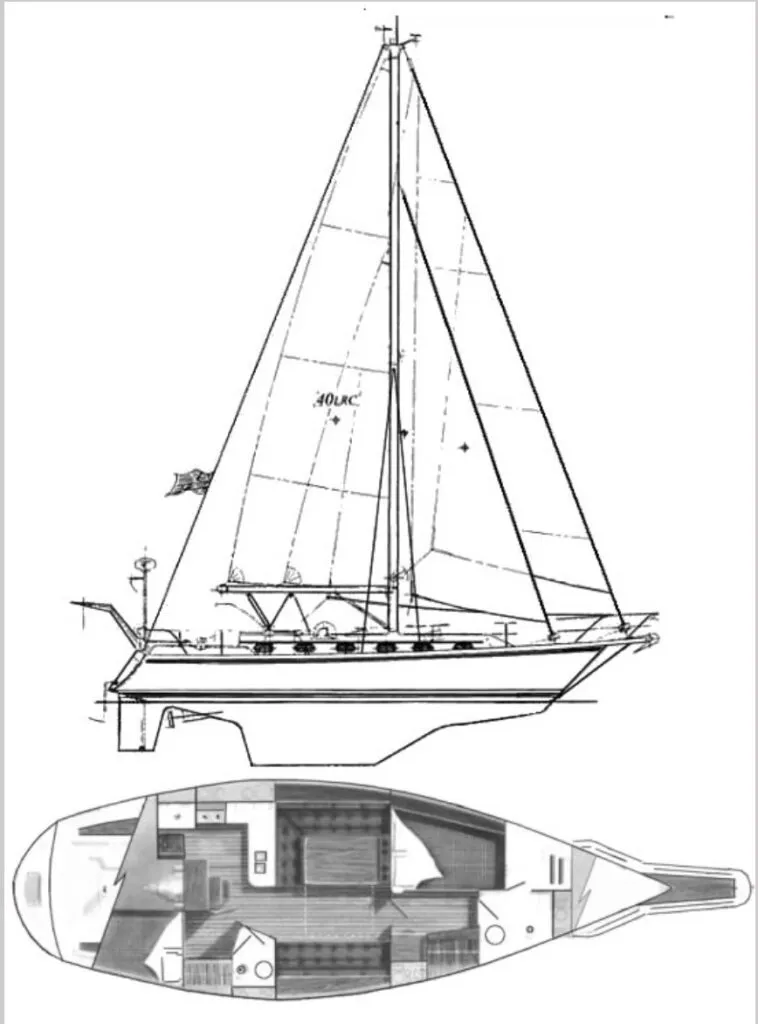

Michael McCreary designed the 40 LRC, which is most often compared to an Island Packet.

It has a relatively fine entry, bowsprit and bobstay, straight sheer, reverse transom, and flat coachroof. The displacement/length ratio is a moderately hefty 281, indicating it has the hull volume to carry necessary cruising stores. A Valiant 40 is 256, a Sabre 38 224, and a J/40 176.

Ballast of 9,500 lb. is 44 percent of displacement. McCreary said its limit of positive stability is 138 degrees, well in excess of the 120 figure many consider minimum for offshore sailing.

The underbody shows a long cruising fin; you could also call it a full keel with a cutaway forefoot and a monster “Brewer bite.” The rudder is skeg-mounted for protection and tracking.

Shrouds are led to chainplates mounted inboard of the toerail, and the genoa track is close to the cabin for narrow sheeting angles.

McCreary claimed the boat tacks through 85 degrees to 90 degrees, but we were unable to approach those tacking angles during our test sail, nor have we heard from any owner capable of tacking through less than 96 degrees, including one who invested $6,000 on flat cut, laminated sails.

Sail area is 739 sq. ft., with a sail area/displacement (SA/D) of 15.3; that compares to a Valiant 40 at 15.5, falling in the general range for offshore cruisers.

The company built 130 40 LCRs since its introduction in 1994.

Construction

McCreary would not provide a complete lamination schedule for publication because he considers the information proprietary and subject to misinterpretation. He said that buyers or owners who want that information should contact him directly.

However, he described the lay-up in general terms.

Hand lay-up of the solid glass hull begins with molds sprayed with isophthalic-neopentyl gelcoat, followed by a skin layer of .75-oz. split-strand fiberglass set in vinylester resin to prevent blistering.

The keel shape is part of the hull mold with a cavity for the iron and concrete ballast that is glassed over.

Though no molded liners or pans are used except in the heads (an appropriate application to deal with moisture from showers and toilet leaks), the hull is stiffened by the bonding in of a molded Integral Strength-Grid System™ that incorporates water and two fuel tanks.

The deck is cored with Marine Tech plywood cut into 2-7/8-in. squares bedded in alternating layers of 1.5-oz. mat and 24-oz. roving. McCreary says that wood is used because it resists compression when deck hardware is installed, which he considers a shortcoming of balsa and foam cores. (Many builders using balsa or foam omit it where hardware is to be installed, and use wood or solid resin/glass.)

Extra layers of glass are laminated around the perimeter of the cabin and cockpit, and radiuses are reinforced with 18-oz. Fabmat.

The Quad-Seal Deck to Hull System™ is sturdy and well done. The deck and hull flanges are bonded with 3M 5200. The inside seam is bonded with copolymer tape. An L-shaped aluminum toerail covers the exterior seam; it is also bonded with 3M 5200 and fastened with stainless steel carriage bolts on 6-in. centers. A stainless rubrail covers the seam between toerail and hull.

Caliber seems to have a name for everything, including conventional bonding of bulkheads to the hull. Caliber calls its method The Multi-Bulkhead Bonding System™. Furniture and cabinetry are bonded in the same manner. A built-up plywood interior bonded to the hull and deck is in many ways preferable to a one-piece fiberglass pan interior.

Chainplates are through-bolted to bulkheads as well as the deck. Caliber calls it the Double-Lock Chainplate System™.

The molded rudder is constructed of a stainless steel plate welded to a 2-in. diameter stainless steel stock encapsulated in fiberglass. When released from the mold, fiberglass tape is laid over the seam to prevent leaks, and the appendage is then faired and sprayed with gelcoat.

Loads on the rudderstock are handled by three supports: a solid stainless steel shoe attached to the bottom of the skeg, a bronze stuffing box at the waterline, and an upper bearing.

To offset the potential for contamination of fuel or water, boats are equipped with “Duel Diesel and Dual Fresh Water” system control panels with independent piping and filters.

However, while at the fuel dock the owners of our test boat complained that the fuel and water fillers are not marked, and are so close to each other that spilled fuel could enter the water filler.

Several owners think the boat’s holding tank incorporates a major design flaw. The 110-gal. integral tank is in the bow below the anchor locker. The aft side of the holding tank extends from the bottom of the hull to the deck, doubling as a watertight collision bulkhead.

The design provides structural integrity, but McCreary confirmed that when pumping out the tank it is critical that vent screens are clean; otherwise, a clogged vent may create sufficient suction on the holding tank wall to cause delamination of the hull. After talking with several owners, we think McCreary has understated the problem.

One owner experienced the problem when flushing the toilet while sailing offshore.

“As I pumped I heard a scary cracking sound in the holding tank,” he said. Upon inspection, he found the vent micro-screens were clogged. “When I opened the Y-valve I heard a major ‘whoosh’ as pressure was released,” he said.

Another owner said a more damaging result occurred under similar circumstances when the screen clogged and the top of the holding tank split away from the hull, creating an 11-in. long crack, not to mention a horrible mess.

Additionally, a full holding tank adds 912 lb. of weight in the bow, according to McCreary; coupled with anchor and rode, we think that is excessive. The holding tank also services the aft head, so waste may accumulate in hoses under the saloon.

The vacuum problem may extend to water and fuel tanks equipped with the same screens. One owner reported the inability to pump water from a tank, though the water pump was operating properly. The screens require cleaning or replacement.

The T-shaped cockpit is comfortable, with 7-ft. 6-in. seats and high backrests. A port lazarette is 32-in. deep and has a 16-in. wide shelf and scallops for organizing spare lines. It also provides access to the aft end of the engine, batteries, and steering controls. There is space for the installation of a cabin heating system and genset. Other features include an ice chest and vented propane locker with room for two 10-lb. bottles. The transom platform has a built-in swim ladder. For sail handling, two-speed Lewmar 48 winches are located on the coaming within reach of the helmsman, but the mainsheet traveler, mounted on the coachroof, requires a shorthanded sailor to leave the helm to trim the main. Two Lewmar 30s are mounted on the cabin top with triple rope clutches for sail control lines. The untapered Selden mast has single spreaders. The test boat was equipped with an optional inner forestay for setting a staysail. Tension on the stay is controlled by an uphaul inside the mast attached to a stainless sliding car to which the stay is attached. When not in service, the stay is secured out of the way to a padeye on deck. The headstay and upper shrouds are 3/8 in.; the backstay and lower shrouds are 5/16-in. The split backstay eases boarding but a single backstay would allow for an integral adjuster to control sail shape. With wide decks, lifelines, handrails and slotted toerail, movement about the boat is easy and safe. A double-roller stainless steel bowsprit moves ground tackle well forward of the stem and furling gear. The split anchor locker on our test boat carried a 30-kg Bruce, 200-ft. of chain and 200-ft. of rode in one compartment, and a 25-lb. Danforth and rode in the other. Joinerwork is nicely done; the 40 LRC looks like a traditional cruising boat—teak and holly sole, teak hull liners and bulkheads. Headroom is 6-ft. 2-in. throughout. The master stateroom forward has an offset double berth measuring 6 ft. 4 in. x 4 ft. 4 in. It’s a nice change from the usual V-berth, though the person sleeping outboard has to climb over his or her partner to get out. We like the head in the bow, but it won’t be as comfortable to use at sea as the aft head. There is a separate shower stall. The L-shaped dinette settee to port is 6-ft. 2-in. long, and converts to a double berth. The starboard settee is 6 ft. The dinette table folds down from the bulkhead. In the galley, the fiberglass sink is located on centerline, where it should be to prevent water from flooding through the drain. The stove/oven is Force 10 and there’s room for a microwave. The 11 cu. ft. top loading icebox drains into a sump pump box at the mast step. The nav station is aft of the galley. The navigator faces a large electrical and instrument panel outboard and communicates with the helmsman by opening a port beside his seat. To starboard is what McCreary called a “day head,” with doors from the saloon or aft berth. The head measures 42 in. x 36 in. and has toilet, sink and a shower; one dealer referred to it as a “telephone booth.” The aft stateroom berth measures 6 ft. 7 in. x 4 ft. 4 in. There’s a cedar-lined hanging locker. Storage space below the berth is shared with an 11-gallon water heater. Access to wiring, plumbing, through-hulls and tank inspection ports throughout the boat are from inside cabinets or behind fascias. The top step on the companionway ladder opens to provide access to the top of engine; if desired, the entire ladder/box can be removed. One owner complained that the engine compartment is inadequately insulated; he added lead-lined foam insulation but is still dissatisfied with engine noise in the saloon. Our test sail was with a Seattle couple that has owned four boats prior to the 40 LRC, most recently a light displacement, fin keel 36-footer. “We didn’t want a full keel,” they said. “But we wanted a good shape, aesthetics, and a full-batten main and cutter rig so we could reef and sail with the staysail in 40 knots of breeze. “The first thing we had to adapt to was the difference in feel and stiffness of this boat. It’s not as much fun as our old 36, but it is easier to sail.” We tested the boat in 0-12 knots of apparent wind on calm waters, setting a 135% genoa on a Harken furler. Considering its displacement, it is no surprise that in less than 6 knots of wind the boat moves only with assistance from the “iron genny.” When windspeed reached 6 knots it made 2-3 knots; at 7-9 knots of breeze we accelerated to 4.5 knots. Then, in 9-12 knots of wind, we sailed at 5-5.5 knots to within 60 degrees of the apparent wind. On a broad reach, we managed to hit 7.2 knots in 10-12 knot puffs. Additional performance information came from another Seattle owner who has logged more than 4,000 miles on his boat. A racer-turned-cruiser, he has pushed the boat hard and has computerized performance data. He replaced the factory main with a flat cut, large roach Spectra sail. “I wanted to find out just how seaworthy the boat is, and how well she sails,” he said. “We sailed 250 miles to weather during a 36-hour trip up the west coast of Vancouver Island. Carried a 120% jib and full main sailing into 5-6 foot seas in steady 15-20-knot winds. I had a mapping program calibrated to my GPS and found that the best tacking angle we could produce was 112 degrees. “Going to weather in winds over 20 knots we furl the jib and hoist an overlapping staysail. We added sail track inside the Dorades to improve pointing and found that when wind speeds reach 20 knots we point 5 degrees higher with the staysail, improve our VMG, and are more comfortable. “On the return downwind we noticed a tendency to roll to windward in heavy seas, even with shortened headsail.” Following an offshore passage from San Francisco to San Diego a cruising couple echoed his sentiments. “When beam and broad reaching in winds around 25 knots the boat will round up if I have too much sail up,” the husband said. “When on a broad reach it gets even worse because the rollers hitting the stern push the stern to leeward, so it’s important to shorten sail early. On the other hand, I don’t think this was any worse than any other boat I’ve sailed on.” A number of owners said they have fitted a feathering Max-Prop to the 50-hp. Yanmar diesel, which improves maneuverability, especially in reverse, and reduces drag under sail. The design and construction of the Caliber 40 LRC make it suitable for offshore use. In decent winds it should give 150- to 180-mile days. Upwind performance is typical of moderately heavy cruising boats; odds are she’ll be motorsailed on long coastal trips to weather. On balance, she’ll cover fewer miles than lighter-weight competitors, but will provide a more comfortable ride in heavy seas. This boat was reviewed on 1 August 2000 and has been updated.

Sailboat Specifications Courtesy of Sailboatdata.com

Hull Type: Fin with rudder on skeg

Rigging Type: Cutter

LOA: 40.92 ft / 12.47 m

LWL: 32.50 ft / 9.91 m

S.A. (reported): 739.00 ft² / 68.66 m²

Beam: 12.67 ft / 3.86 m

Displacement: 21,600.00 lb / 9,798 kg

Ballast: 9,500.00 lb / 4,309 kg

Max Draft: 5.08 ft / 1.55 m

Construction: FG

First Built: 1995

Builder: Caliber Yachts (USA)

Designer: Michael McCreary

Make: Yanmar

Model: 4JH3 (B)E

Type: Diesel

HP: 56

Fuel: 212 gals / 803 L

Water: 179 gals / 678 L

S.A. / Displ.: 15.3

Bal. / Displ.: 43.98

Disp: / Len: 280.9

Comfort Ratio: 32.39

Capsize Screening Formula: 1.82

S#: 1.75

Hull Speed: 7.64 kn

Pounds/Inch Immersion: 1,471.32 pounds/inch

I: 50.50 ft / 15.39 m

J: 17.25 ft / 5.26 m

P: 45.75 ft / 13.94 m

E: 13.25 ft / 4.04 m

S.A. Fore: 435.56 ft² / 40.46 m²

S.A. Main: 303.09 ft² / 28.16 m²

S.A. Total (100% Fore + Main Triangles): 738.65 ft² / 68.62 m²

S.A./Displ. (calc.): 15.3

Est. Forestay Length: 53.36 ft / 16.26 m

Deck

Accommodations

Performance

Conclusion

Market Scan Contact

1998 Caliber 40 LRC CenterPointe Marine

$145,000 USD 414-622-1114

Milwaukee , Wisconsin Yacht World

2009 Caliber 40 LRC LITTLE YACHT SALES

$219,000 USD 281-916-4936

Kemah, Texas Yacht World

2004 Caliber 40 LRC Anacortes Yacht Brokers

$220,000 USD 804-375-5005

Deltaville, Virginia Yacht World