Securing a small boat between pilings in a wrong-sized slip is a common challenge. The dock line angles from the dolphins (outlying pilings) are too narrow for a beam wind, allowing the boat to dance around, increasing forces, chafe, and even making it difficult to stand in the cockpit. During a recent winter near-gale we measured dockline forces on several smaller boats that reached four times higher than the static wind load. If the recommended size dockline was used, the rope would be operating beyond its working load limit in real storms and could fail. Increasing the line diameter would result in more jerking and chafe.

The best cure for a dancing boat, in most situations, is fore-aft spring lines (see Practical Sailor, Spring Lines for Storm Preparedness, June 2016). Not only do they reduce the fore-aft motion of the boat, they also relieve load from the bow and stern lines and provide redundancy if something breaks. However, spring lines are occasionally impractical. So what are the alternatives?

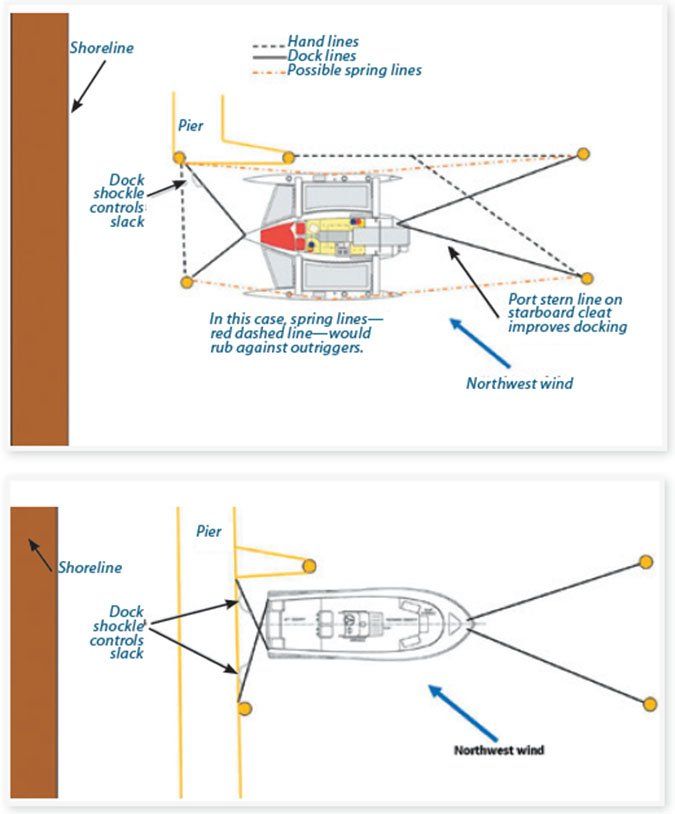

Snubbers are often suggested. Typically sailors install these on windward lines that are obviously overloaded. We installed Dock Shockles (very heavy duty webbing-covered bungee cords by Davis Industries) on the windward side of a Corsair F-24 trimaran. As expected, they immediately stretched out to full length under the sustained wind load alone, providing limited force impact reduction. They also increased the range of motion, resulting in the need to tie the boat impractically far from the dock.

It also became clear that it was not wind gusts or waves that were causing the trouble, but the bouncing. If we could eliminate the rebound by keeping slack out of the lines, the dance would be interrupted and the forces would be considerably less. It is here where we begin our investigation.

Trimaran (24 feet)

The extreme, 18-foot beam of our 24-foot, 1,600-pound test boat (Corsair F-24 MK I) makes finding a slip challenging. We can fold it for docking in just a few minutes, but it is a hassle and the sides of the amas become fouled with growth. We could tie to a bulkhead, but the tidal range of 6 feet makes that risky. Additionally, the outrigger hinges would take a continuous pounding. Our chosen slip is an end slot, which allows us to overhang into open space. Unfortunately, the slip was too long for the boat, over 45 feet end-to-end for a 24-foot boat. As a result, the stern line angle is poor for cross winds.

On the first day of testing the wind was 25 knots gusting to 45 knots from the port quarter. Every 5-10 seconds the boat would launch itself aft, gather some slack, rotate slightly, and then surge forward, slamming against the stern lines at an awkward angle. The motion was so quick and violent it was difficult to stand upright in the cockpit.

A load cell on the most heavily loaded lines recorded forces ranging from 0 to 550 pounds. First, we tried reducing line size, from -inch down to the 3/8-inch size generally recommended for a boat this size. The peak force dropped to 400 pounds and the range of bouncing increased. However, these forces will double at 60 knots and triple to 1,200 pounds in a weak hurricane.

Even without including knots (which can reduce strength 40-60 percent), sharp turns, chafe, and age, the working load limit of 3/8-inch nylon rope is 576 pounds, and the working load limit for -inch rope is 960 pounds. We needed to cure the bouncing before the real winter storms arrived.

We considered spring lines on the port side, where they would do the most good, but this was impractical. We tried simply hauling the starboard bowline tight. The bouncing stopped and the peak loads fell by 70 percent The lines stopped chafing on the cleats and chocks. However, we couldnt leave the lines hauled tight, because the boat must be allowed to rise and fall with the tide, or as much as 10 feet when hurricanes are included. Even with such long lines, we need to leave about 12 to 18 inches of slack.

Next, we inserted a Davis Dock Shockle in the starboard bow line, stretched so that it was just short of full extension at the highest and lowest tides. Although the Dock Shockle could not hold the full wind load (Dock Shockles begin to extend at 30 pounds and reach full extension at 90 pounds), it was enough to control the rebound, and peak loads were about the same as with the bowline hauled tight. (Dock Shockles working range is 15 inches.)

Weve been watching her close through the full range of tides and numerous storms; she now sits quietly in all conditions.

Powerboat (22 to 26 feet)

There are several similar boats in the marina. When the owners first moved in, their boats were dancing all over the place. Like the F-24, they were in slips that were far too long (22-to 26-foot boats in 45-foot slips), resulting poor bowline angles and crazy motion. Additionally, by the time they allowed enough slack for the tide, the boats were rather far from the dock and had to be hauled in to load passengers.

We added Dock Shockles to both stern lines, again adjusting the stretch to allow full extension at the extreme tides. Motion was reduced to nothing, chafe on the lines stopped, and the boats rested quietly in the most blustery weather, not too far from the dock.

The obvious shortcoming of attempting to control slack on the leeward side is that the wind will shift and it will become the windward side. In our case, this is a minor problem, because the pier is parallel to a treed shoreline, blocking strong winds from striking at deck level. The starboard side of the trimaran is south, not a direction known for strong winds in the Chesapeake. Thus, north and west winds were our only real concern. And as you recall, we did try the Dock Shockles on the windward side; they helped a little and they will do no harm. So long as you install them so that they do not exceed their rated extension (about 15 inches) before the rope takes the load, they last for years.

What about using thin nylon rope? Dock Shockles will struggle with a boat over 25-30 feet. One option is to double up and install two side-by-side for additional capacity. Alternatively, thin rope, about 50-70 percent the required dockline size, in place of the shockle may a more practical shock absorber. Adjust the line to be about 1-2 feet shorter than the dock line, and the thin line will be able to stretch easily enough at the extremes of tide.

In a strong wind, the main docklines will take the load. Because this thin line will be working at as much as 20 percent of its working load limit, the life expectancy is only about one year, but the cost will only be a few dollars. And as we said earlier, a full set of spring lines is a better solution. But this is one more tool to quiet the dancing boat.

Dock Shockles come with stainless steel snap hooks and Dyneema rope Grabbers-loops that attach like luggage strap. The Grabbers can slip if not firmly set. The loads are not high, so you may do better with prusik loops tied from -inch webbing or -inch line. We also found they were easier to adjust if one end was simply secured to a deck or dock cleat with a short length of light line. Davis also suggests installing Shockles by tying a clove hitch in the line, around the carabiner, but that will weaken the rope.

What about other dockline snubbers? These are generally much higher force, lower range of motion, and are designed to be used on the windward side. We will be looking at these soon.

Conclusion

There is simply no substitute for visiting your boat on a really windy day to see how she is moving. This will take several visits, since every wind direction presents new challenges. The key to reducing chafe and force is often eliminating rebound by controlling slack through the use of Shockles, thin nylon line, or some other reasonable stretchy gear. Spring lines are even more effective and provide additional safety, but they arent always practical. Rubber snubbers can be helpful on short docklines. The best approach depends on the slip, the boat, and the weather exposure. This is just one more tool.