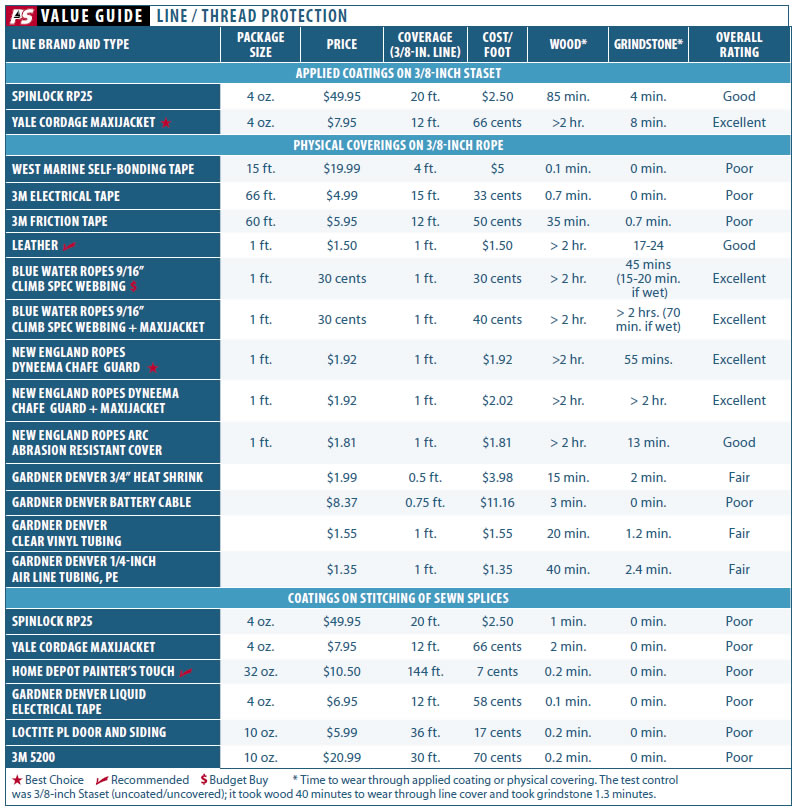

Photos by Drew Frye

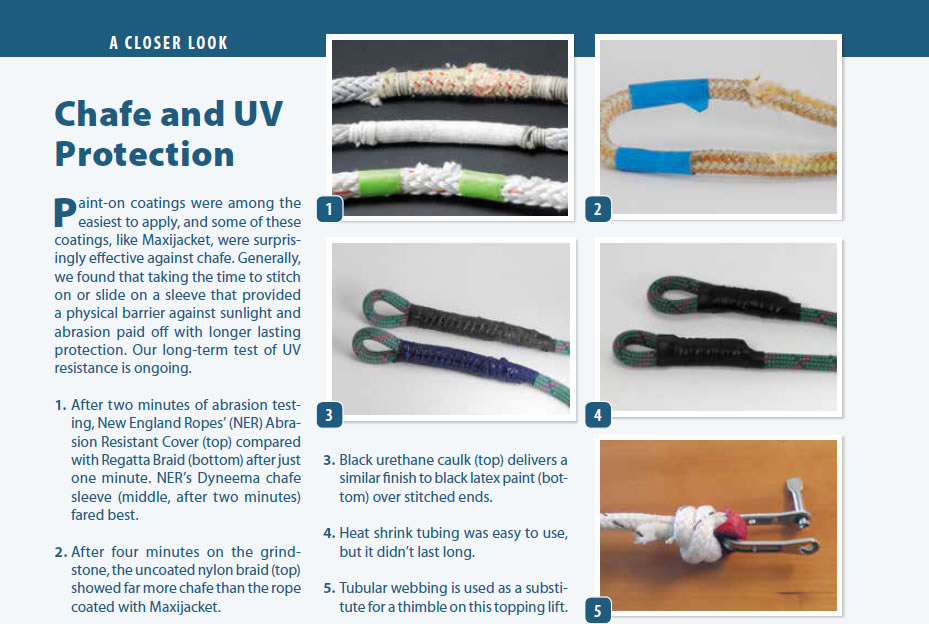

Last fall, we reported on how to build strong, hand-stitched eyes in the ends of a rope, a skill particularly useful for older halyards and sheets that are too stiff for a typical bury splice (see PS October 2014 online). We also warned against the ravages of ultraviolet rays (UV) and chafe on the stitching, since so much of the strength lies vulnerable on the surface. In this report, we look at means of protecting stitched splices from UV and chafe.

For this evaluation, we were not interested in heavy-duty fabric and plastic chafe guards like those used for dock lines-and which weve previously tested (see PS July 2011). Instead, we were looking for more compact applications that reduce wear in less time, with less expense and less bulk-this is particularly important for splices, which are often snugged up into sheaves. In a future report, well look at how well different rope types resist chafe.

The art of protecting splices is as old as splicing itself. On traditional craft, sailors use tar, paint, or varnish to protect their seizings, and riggers use worming, parceling, and serving to seal laid lines and wire rope. But for the modern sailor who relies on braided core-cover line, Spinlock and Yale Cordage have both introduced brush-on rope coatings that promise to improve the holding ability of clutches, reduce core slippage, and reduce cover wear. These products are just a start.

When we began scouring the planet for protective concoctions, readers, dockside gurus, and tall-ship crew suggested a range of options-latex paint, liquid tape, self-bonding tape, heat-shrink tubing, and the list goes on. In the world of performance sailing, spectra sleeves have been used to fabricate some very impressive-looking halyard splices. Among the cruising community, tubular nylon webbing and leather have long been durable and economical options.

Needless to say, we had a lot of options to choose from, and narrowing the test field was the first of many hurdles we had to overcome. But now that weve built a new chafe-testing machine, put dozens of samples through its destructive cycle, installed several samples on our test boats, and left dozens more in the sun and weather to age, weve got a good understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the various options.

What We Tested

Many splices such as a tight splice to attach a mainsheet line to a becket block or a loop buried inside a lashing see little abrasion, so keeping the sun and salt spray off the fibers should be enough. For this purpose, everything from varnish to latex paint to polyurethane caulk was suggested to us. Where UV and water damage are your only concerns, a surface coating makes perfect sense.

Some might say that the outer cover of a double-braided rope offers enough protection to splices. However, while testing stitched eyes, we stumbled across a surprising discovery. In used lines as thick as a half-inch in diameter, the core had weakened just as much as the cover. Clearly, damaging UV rays penetrate more deeply than we thought.

Although a braided rope cover may extend the life of an ordinary buried splice, the cover isn’t woven tightly enough to fully prevent the ravages of UV. Combine the minimal UV protection with the tight radius bend at a halyard shackle, and that worn splice at the end of your halyard could be a ticking time bomb (no doubt set to go off on a moonless night at 2 a.m.).

Testing by rope manufacturers confirms that UV is a major source of degradation in the outer 5 millimeters (1/5 inch). That means UV damage can reach nearly to the center of any 3/8-inch line. But there are other factors at work beside UV. Coating a splice can also help protect against the abrasion caused by embedded salt crystals, and can prevent the fiber-to-fiber abrasion that can occur as a splice works under load.

Why not simple heat-shrink, or tape? Considering the amount of damage that occurs below the surface, a penetrating treatment has several advantages. Such a coating could protect the inner fibers directly, settling in areas that arent subjected to weathering and wear, and could help bond the fibers together to prevent inter-fiber wear.

Penetrating rope coatings have been around for some time, but theyve taken on a greater role as high-modulus ropes have entered the market. Many of these ropes are generally more vulnerable to UV. Two of the better-known coatings on the sailing market-Spinlock RP25 and Yale Maxijacket-promise to penetrate all the way to the core to provide chafe protection. These coatings make sense for splices, especially those that need to be kept compact.

Keep in mind that it is unrealistic to expect simple coatings to protect against chafe in the same way that a heavy-duty, ballistic nylon chafe sleeve can. Where rough treatment is expected-genoa sheets, mooring lines, and halyards-a physical covering is clearly best.

Although this series of tests was focused on products that provide quick and effective protection for splices, we also looked at a cross-section of physical, sleeve-type coverings. These included traditional coverings such as leather (a PS favorite) and more modern alternatives like Dyneema webbing, nylon webbing, heat-shrink tubing, and various tapes.

Our testing process was two pronged: abrasion and exposure. For the abrasion testing, sewn splices that had been coated were tested on our newly redesigned abrasion machine. For the exposure testing, coated sewn splices and sewn materials were left in the weather. This article focuses on the abrasion results and weathering during field testing; the results of our long-term exposure testing will appear in a later issue.

What We Found

In our search for the best way to protect a stitched loop or splice, we made several interesting discoveries.

None of the liquid coatings (Maxijacket, RP25, latex paint, several caulks, varnish) reduced line strength in the short term.

Tubular nylon sleeves (webbing) are extremely chafe resistant, but the chafe resistance drops considerably when wet. Tubular nylon chafe gear should be carefully watched when its wet, especially when subjected to high cyclical loads like those imposed on mooring pendants, kedges, snubbers, sea anchors, or drogues.

Stitches made with plain old polyester whipping twine are surprisingly chafe resistant. This surprised us. In the wood abrasion testing, only a few stitches had failed when roughly 30 percent of the rope cover was gone. Although stitches will need protection from UV, there is no merit to the argument that sewn eyes are inherently fragile.

Steer clear of light-duty heat shrink for chafe protection. A sample installed on our test boats genoa sheet failed within days. We stripped back the heat shrink and replaced it with nylon tubular webbing, which remains virtually wear-free after a year.

Specialized, impregnating coatings really work. We put Spinlock RP25 on a furling line. It has clearly reduced the wear rate, with very little effect on handling. The furling line also wraps better, making it easier to furl and unfurl. Weve been testing Maxijacket on docklines and snubbers. In these cases, wear has reduced effectively to zero, a great improvement.

Stay away from tape. On our test boat, all of the tape coverings on lines that are handled soon began peeling away.

The following is a detailed report of our finding for each type of product.

Yale Maxijacket

Made by Yale Cordage, Maxijacket is a quick-drying, waterborne polyurethane coating. It soaks in deeply and stiffens the line considerably. However, the 10-fold improvement in chafe resistance against both wood and grindstone was very impressive.

Field testing on mooring lines and snubbers delivered the same remarkable results, which we found particularly stunning for a product that brushes on in a few seconds and cleans up with water. Splices can also be dipped, firming them up a bit, locking them together, and providing even deeper chafe protection. The coating dries to the touch in a few hours, and is ready for use in 24 hours. Maximum wear protection is about two weeks.

Formulated specifically for protecting rope, Maxijacket is a winner. Some users have commented that the colors can rub off onto the deck; we tested only the clear product and were happy with it. Prices ranged from $7 for a 4-ounce jar to $50 per quart.

Bottom line. Useful on both tucked splices and sections of line prone to light abrasion, Maxijacket is surprisingly handy. It was is our Best Choice for protecting polyester line.

Spinlock RP25

Made by Spinlock, RP25 is a relatively expensive coating that is intended to reduce cover-core slippage, increase durability in clutches, and reduce chafe. Solvent based, it soaks in deeper than Maxijacket, but it is a little messier to apply.

While it did not prevent chafe as well as Maxijacket, its main purpose is to bind the fibers together to prevent core slippage on highly loaded lines. In that regard, it performed admirably. It provided excellent service on our jib furling line, and well continue to explore other applications.

RP25 slightly stiffens line, so test a section before applying to the whole lot. Generally, it is applied only to critical sections of the rope, not the entire rope. We found it priced at $50 for 250 milliliters (8.45 ounces), or $200 for one liter (33.81 ounces).

Bottom line: The high price will likely deter cruising sailors, but for racing or other performance-oriented sailors concerned about chafe or core slippage in high-modulus lines, we Recommend it.

Varnish

Although varnish offers only limited value for chafe protection, even when allowed to soak in, it is a time-honored protectant. Two coats do the job. We didnt compare brands, but cans run about $20 to $30 per quart.

Bottom line: If you want to protect a handsome stitching job and still show it off to your dock mates, this semi-transparent, readily available coating is a cost-effective option.

Gardner Liquid Electrical Tape

Liquid electrical tape is a quick-drying, solvent-based product that is a poor substitute for other electrical insulators, and its performance as a protectant for cordage is uninspiring. We applied three coats, and although it was easy to apply (the brush is attached inside the lid) and offered added grip, the coating quickly rubbed off. We found a four-ounce bottle for about $4.

Bottom line: Not recommended. It doesn’t resist chafe well and succumbs to weathering quickly.

Latex Paint

Cheap, easy to apply, easy to maintain, and available in many colors, latex paint is commonly used to protect rope seizings on tall ships. Expect it to be relatively durable and provide good UV protection. Two coats are recommended. It costs about $16 per quart.

Bottom line: Recommended for low-abrasion applications where you want to show off your handy work.

Loctite

Weve been using Loctite PL Door and Window Sealant as a low-cost alternative to 3M polyurethanes for a decade. The rubbery texture feels odd in the hand at first, but eventually, we learned to like it for halyards and other lines that tend to get slippery. A 10-ounce tube is available at big box home supply stores for less than $6.

Bottom line: This product is messy to apply and not very durable, but it makes lines easier to grip.

3M 5200 Polyurethane Sealant

Like Loctite PL Sealant, 3Ms 5200 adds grip to a line, but it doesn’t last. Try it on a scrap rope next time you have the caulking gun out, and see if you like it. It isn’t cheap at $21 for a 12-ounce tube.

Bottom line: This is not worth buying solely for use on ropes, but if you don’t mind the mess and accept that it probably wont last long, using left over 5200 on your ropes will help add grip.

Whipping Twine

We used the same No. 8 whipping twine for chafe protection as we used for seizing our stitched splices. Because line diameter shrinks under load, apply the twine very tightly while the rope is tensioned, and consider using a serving mallet. For maximum durability, make a second overlaying wrap. You need more twine than you might think-15 feet of twine for each half-inch eye. Coating the finished whipping with latex paint or varnish should add durability and reduce slipping.

Bottom line: This process takes longer than others, but is cheap and will provide relatively long-lasting protection for those who prefer a traditional look.

Tyco Heat Shrink

We found that the Tyco Electronics Battery Cable Heat Shrink two-pack of 6-inch-long heat shrink tubing (1-inch diameter before shrinking, suitable for line diameters 7/16 to inch) at Home Depot for $8. This covering failed after just two days on our genoa sheet. It might hold up in some application for ropes, but we it isn’t preferable to other options.

Bottom line: Not recommended.

Gardner Denver Heat Shrink

A polyolefin heat-shrink tubing, the Gardner Denver heat shrink had -inch inside diameter before shrinking and was sold at Home Depot for $2 per two-pack. The 6-inch-long tubes, suitable for 3/8-inch lines, were made of a much heavier material that the Tyco brand. We used this to protect seizings on the ends of a short tether, and it is holding up fine so far. It is certainly quick and easy to apply, although a special size is needed for each size line.

Bottom line: This heavy-duty heat shrink provides a neat finish for applications with limited abrasion and snagging potential. Recommended.

Shields Vinyl Tubing

Shields clear, vinyl plumbing tubing is stiff, difficult to secure, and it wears as fast as the rope cover itself. It costs about $1.50 per foot for 3/8-inch tubing.

Bottom line: Use this material for plumbing, not chafe protection.

Polyethylene Airline Tubing

Though it wears better than vinyl, this product is hard on the rope, very stiff and difficult to secure.

Bottom line: This tubing belongs on truck compressed air lines, not rope.

NER Climb-Spec Tubular webbing

Made by New England Ropes (NER), the Climb-spec Tubular Webbing is more durable than the line it protects; it has worked as chafe protection on our dock lines for over 20 years. Secured with stitching or seizing, the tubular webbing requires only occasional inspection.

The frayed ends where the fabric is cut fuse easily when heated; no further finishing is required. While the appearance isn’t as neat as others, the webbing has proven extremely durable and practical. The only potential weakness is chronic chafe on wet surfaces. Although it has worn very well on dock lines or snubbers in our field tests, we would not recommend it for mooring pendants of larger boats. The 9/16-inch webbing fits up to quarter-inch line or 3/16-inch splice, and it costs about 30 cents per foot; 1-inch tubing fits up to half-inch line or 5/16-inch splice (about 50 cents per foot); and 2-inch tubing (about 70 cents per foot) fits up to 1-inch line or 5/8-inch splice.

Bottom line: Heavy-duty physical coverings, like webbing and leather, are definitely the most durable answer for chafe protection. NERs Climb-spec tubular webbing is our Budget Buy for splices that will see heavy wear.

Leather

We tested 3/32-inch thick samples of leather supplied by several canvas shops and sailmakers. The handsome, traditional material can be sewn to any conformation. Stitching is left exposed, something that you need to plan for when sizing and designing chafe gear. Like any natural material, there is significant variability-our samples lasted from 16 to 25 minutes on the grindstone, much longer than bare stitching or polyester rope, but far less than tubular nylon webbing.

We used relatively thin leather in order to compare it with webbing and to suit our test machine. Thicker leather will be more durable. Weathering will depend upon the grade. In our experience, leather will begin drying out and cracking at the same rate UV attacks most synthetics, although treating it with leather protectant will prolong life.

Bottom line: Traditionalists will find leather to be effective and attractive, although most sailors will prefer the more durable and less labor intensive tubular webbing. Leather is very durable in thicker grades.

NEr Dyneema tubing

NERs Dyneema tubing is very similar to nylon webbing, except it is thinner and far more durable when wet. Unlike nylon webbing, the ends of Dyneema tubing are difficult to fuse by melting and should either be whipped down or tucked in. We found a standard whip-lock worked well. If you are trying to melt the ends, slide the webbing over a mandrel (a craft paint brush works well) and melt in place, spinning and molding with palms and fingers. The only serious limitation is that it will not fit over large splices.

Prices range from about $1.12 per foot for 3/8-inch inside-diameter tubing to about $2.50 for 1-inch inside diameter.

Bottom line: Much denser than any Dyneema line cover, Dyneema tubing will last longer than the line. It is our Best Choice for heavy-duty protection.

Friction Tape

Friction tape is primarily intended for waterproofing electrical splices, but it has proven to be quite durable as chafe gear on dock lines and bridles. It does not stiffen with age like many tapes, and stands up very well to frequent wetting and even submersion. It does not cut easily. However, its tar-like coating can rub off, making it messy.

What impressed us most was the way it wore on the chafe testing machine, lasting 10 to 20 times longer than every other tape. It is also useful under larger-diameter whippings as parceling (under-wrapping) to keep outer wraps from sliding. Prices run about $6 for a 50-foot roll.

Bottom line: We Recommend keeping some friction tape on hand for emergency wraps, or as an under-layer (parceling) when serving or whipping splices or ends of larger-diameter lines.

3m Electrical Tape

Simple electrical tape (we used 3M) is quick and easy, but it wont stand up to handling, and UV will dry it out in less than two years. But if it is reapplied every few years during a routine rigging-tape replacement, it is reasonably effective against UV. Since it is available in many colors, color-coding is easy. Costs run about $5 for a 22-yard roll.

Bottom line: Electrical tape is fast but not very effective.

West Marine Self-Amalgating Tape

Weve tested a variety of self-amalgating tapes (see PS March 2001 online). Marketed for wrapping turnbuckles and sharp spots on rigging to prevent line snags, accidental cotter-pin removal, and sail tears, self-amalgating tape also is used to tidy wiring bundles and seal hose leaks.

As far as serving as splice protection, it should provide good UV protection, but we found that it tended to peel off under friction, and it didnt hold up well at all to abrasion. At $20 for a 15-foot roll, it isn’t cheap either.

Bottom line: Not recommended. It is easy to apply, but expensive and ineffective against wear.

Conclusions

The Achilles heels of sewn eyes and lines are UV and chafe. We found that naked stitching is not as delicate as we feared; it wore nearly as well as the polyester rope cover. However, UV will reduce that durability over time.

As for the coverings and coatings, the best choice depends on the ropes application. Something as simple as latex paint can block UV where there is little wear; impregnating products like Maxijacket and RP25 can provide increased durability for ropes; and physical coverings provide protection against the roughest use.

The standout products in this review were Maxijacket and Dyneema tubing sleeves. Who would have thought a simple coating could increase line durability tenfold? While Maxijacket didnt protect the surface stitching of sewn eyes very well, we like it for tucked splices in nylon and polyester. It is particularly useful on ground tackle and dock lines, and for locations where lines run and chafe gear wont fit. However, it stiffens the line and it is not very effective on high-modulus polyethylene (HMPE) line, so it isn’t ideal