For nearly 50 years, our boats electronics systems have operated according to standards developed through the National Marine Electronics Association (NMEA). Today, our onboard electronics communicate using either the older NMEA 0183 or the current NMEA 2000 data-the digital language that our marine devices speak. Sadly, this is not the same language that our personal electronics or the wireless Internet speaks-leaving the door effectively closed to app developers who might want to create new apps based on that data.

The big marine electronics makers and a small number of software development companies have created Internet-friendly hardware and wireless apps that integrate some NMEA functions, but until now, there has existed no universal, open-source code version of NMEA-a translation, so to speak-that app developers around the world could use to tap into all of the NMEA data streaming around our boats. Instead, boaters live in a fractured world of proprietary apps that work with proprietary hardware and use only the most basic NMEA data-and we pay proprietary prices.

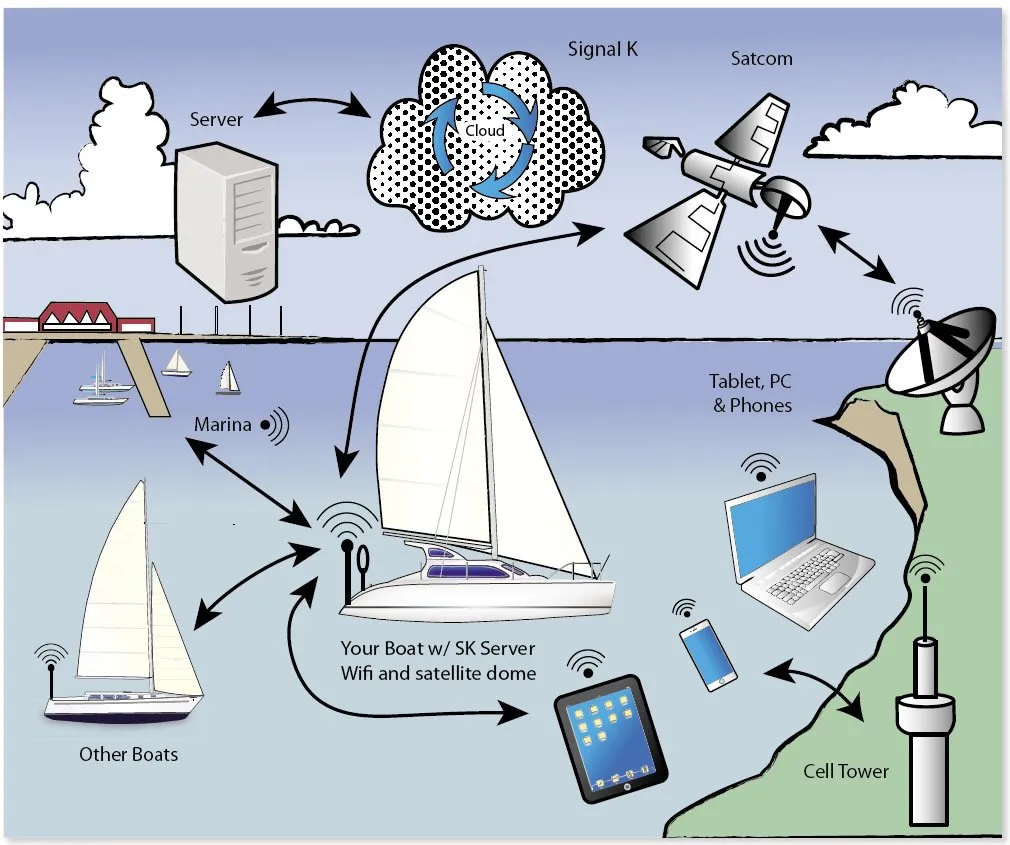

Illustration by Regina Gallant

An Internet-based, universal communication standard called Signal K promises to change all that. With the NMEAs blessing, a largely volunteer initiative created the Signal K platform for app developers to make apps that can be used across the spectrum of NMEA data. Bit by bit, onboard NMEA data is being translated into an Internet-based format that developers can use.

When fully developed, Signal K will open the door to a wide range of low-cost substitutes for expensive proprietary programs. In past tests, we looked at examples of open-source navigation programs like OpenCPN (see Practical Sailor July 2013 online). Signal K will allow a much greater range of apps. Software developers have been watching the Signal K project over the past two years, and their interest is building as it appears to be coming to fruition.

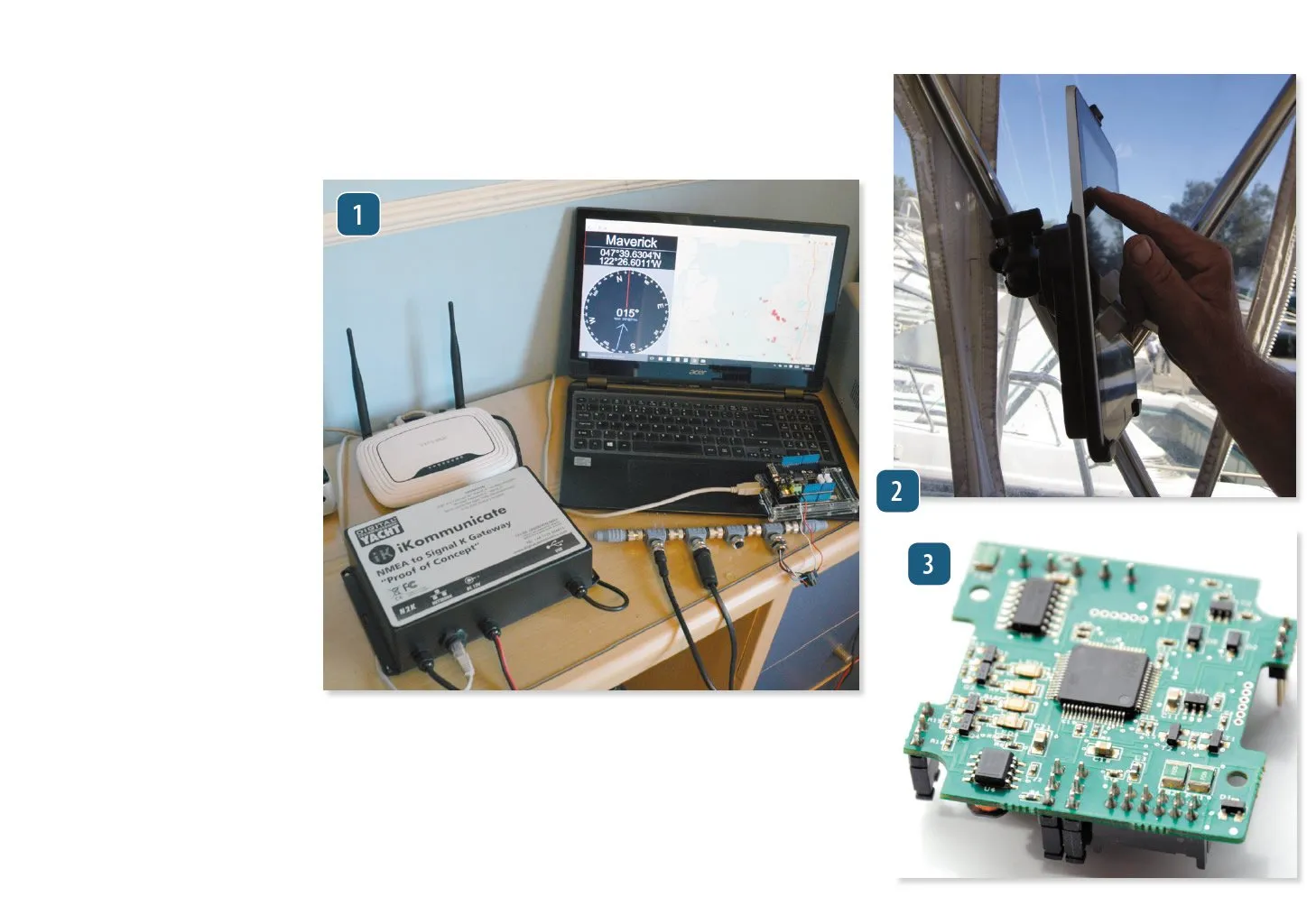

In October, Digital Yachts, a U.K.-based marine electronics manufacturer and one of the key proponents of Signal K, announced that it would be delivering a Signal K gateway that it calls iKommunicate in the spring of 2016. The gateway is a piece of hardware that translates NMEA data into Signal K for use in the wide range of Signal K apps expected on the horizon. It is anticipated that by the time the gateway is released, at least a dozen apps will be operating using Signal K, which is freely available to app developers, unlike the software used in conjunction with existing NMEA gateways.

Photos by Bill Bishop and Ron Dwelle

Signal K overview

The Signal K communication standard aims to solve the problem of how to get your boats data off of the boat in a universal and inexpensive way. Its purpose is to not only enable communications from the boat to the Internet, but for the first time, to give app developers the ability to easily create niche apps for your boat that big companies might not want to pursue.

If you look online for boating apps for your smartphone or tablet, you will find hundreds of them. But only a few of them use NMEA data. Many rely solely on sensors within your smartphone, like the internal GPS, to provide navigation data. And those that do use NMEA data, such as depth or wind speed, require that you buy proprietary hardware and proprietary apps. It is as if you would need a different headset for every audio app you have on your smartphone.

Putting it together

Signal K comprises three pieces. The first is the gateway. This takes NMEA data, both the 0183 used by older devices and its newer cousin NMEA 2000, and translates it. This process does two things. It first takes a packet of data-called sentences in NMEA 0183 and PGNs in NMEA 2000-and parses them into individual pieces of data. As an example, lets look at a typical NMEA 0183 sentence such as the one the NMEA labels RMC, for recommended minimum navigation information. It might look like this:

$GPRMC,133119,A,5808.038,N,01131.000,E,006.4,074.4,230315,004.1,W*6A.

Buried in this string of information is universal time, latitude, longitude, speed over ground, track angle in degrees, date, and magnetic variation. The Signal K gateway breaks down the sentence data into separate pieces and gives each comprehensible names such as latitude, longitude, or speed over ground.

This enables the gateway to send out bits of information that have easily understandable names, and there is a time stamp for each, so we know how old the information is. These bits of data are then sent to the Signal K server.

The server is a small, inexpensive, single-board computer on your boat with an SD card used for archiving data. The server places the data into a schema, an organized database. You can see how the schema is set up at the Signal K website (www.signalk.org/specification).

At the top of the schema is Self. This is identifying information about you. Below this, we have Vessels. Vessels holds the information about not only your boat but all the other boats in range of your boats Automated Identification System receiver (if equipped with AIS) and other sources. Under this is the Vessel heading. This is the specific information about your boat. This is in turn is broken down further into subsections such a navigation, propulsion, tanks, and so on.

The schema provides a consistent and standardized way of storing not only the translated NMEA data, but much more. It has the ability to store other information, including sail configurations, offsets from the bow to the depth transducer, or offsets from the bow to the GPS receiver for precise geo-location. It can store call signs, marine identity (MMSI) numbers, routes, waypoints, cruising notes, and so on. Each piece of information such as course over ground has a permanent and unique address on your onboard server.

Similar to a website address-like www.practical-sailor.com-the permanent address on the server for a category of Signal K data (depth, for example) is simply a location on the server, and the data stored in that location can change. The schema can grow, with new addresses added as new kinds of data are added. Each new type of information that is added will get a unique address. This allows app developers to add new data elements to the schema without disrupting the functionality of older apps.

The schema also contains metadata-additional layers of information related to the primary data. Since Signal K is designed to be universal, its providing underlying information of use to app programmers.

Take engine gauges, for example. What are the upper and lower alarm limits and the operational ranges? What are the measurement units being used, such as pounds per square inch (PSI) or revolutions per minute (RPM)? Whats the name of the gauge? Having this information embedded in the schema allows app developers to use existing generic gauges (created with the programming language Java) and lets the system fill in the blanks instead of creating custom gauges for each of the myriad gauge types and measurement units.

Sharing with the world

The server has a second job. This portion of the software manages the data transmittal to other devices such as smartphones, PCs, tablets, other boats, and to servers in the metaphorical Cloud. The goal of Signal K is to make it as easy as possible for developers to get the information they need for their apps. You control the flow of information to the apps you use.

You can ask your onboard server to send only the depth below transducer to a specific app. Or, you can allow an app to access all information in the propulsion subsection of the schema such as RPMs and oil pressure. The apps can receive the data as it streams, or just ask for only the data that has changed.

Lastly, the server manages the interfaces to the outside world and the security layers to protect your information. The server has discovery service similar to what your smart devices have. When you come home, your smartphone or tablet can be set to automatically recognize your WiFi router and to switch to using the WiFi signal instead of cellular data while at home. Signal K does the same thing.

The last part of a Signal K system is the router. This makes your boats information available to mobile devices, the Internet, and other boats that are within your WiFi range. Routers can vary from simple and very inexpensive systems that operate only on your boat, to more elaborate configurations with external antennas that can have WiFi ranges of up to seven miles or more. One of the big pluses of having a Signal K system is that your boat now has a WiFi hotspot that everybody on board can share.

Basic Requirements

So what is needed to make all of this work on your sailboat? First, you need a certified NMEA gateway. These initially will cost about the same as the current NMEA gateways, around $200. This price is expected to rapidly drop over the next couple of years as volume increases. Second, you need a server. Although the Signal K project hasn’t selected the specific recommended server hardware yet, the software is now operational on any number of inexpensive Linux-based processors such as the Raspberry Pi and others. Finally, you need a router to communicate with the world.

In practical use, Signal K promises something for every type of sailor- racers, cruisers, even daysailors.

Signal K is designed to hold ever-increasing types of data-even non-NMEA data. It has the ability to interface with highly specialized, embedded processors that can be used for specialized tasks and applications. This allows both the serious racer or the occasional regatta participant to acquire high-end, polar-based racing app tools that previously were only available in expensive and proprietary systems. Mobile apps using Signal K can do applications that previously were confined to specialized racing processors and PC-based systems.

For offshore racers and serious ocean cruisers with satcom, Signal K apps could be used to access Cloud-based, gridded binary (GRIB) weather files and enable sophisticated GRIB-based weather-routing. It can also be used to create a range of tracking apps that allow others to follow your boat on the Internet. Since Signal Ks data can be substantially compressed, satellite up-link time and costs stay low.

Signal K can also benefit cruisers. In the Signal K world, boats can communicate with each other and the world. Apps will enhance and improve your sailing performance. Sharing waypoints, routes and your location with others becomes easier. A marina could recognize your boat as you approach and automatically send you docking information.

Aboard a daysailer, a Signal K system could allow for a compact and fairly sophisticated system that doesn’t require a pricey multifunction display (MFD). For example, you could just have an NMEA 2000 wind instrument, along with numerical depth, and speed transducers. These, along with a WiFi-enabled server, a gateway, and a tablet computer loaded a good charting and racing app would give your boat competitive racing or navigation tools equal to bulkier and more expensive MFD systems.

The Bottom Line

Signal K is an emerging, low-cost technology that is rapidly gaining traction in the marine electronics world. At the recent NMEA conference, Signal K was the most popular presentation at the event, and several major new companies have joined the project as a result. With Signal K, your boat will no longer be an island.

Practical Sailor will be tracking this project carefully. Both the required hardware and Version 1 software will be available in just a few months (early 2016), and many new apps from performance sailing to wave height and period measurement, and much more are currently in development. For more information on Signal K, check out www.signalk.org.

SignalK has gone a long way since this review. It would be awesome to see an update😎🌴⛵️