Sacrificial anodes are used to protect a sailboats metal components from galvanic corrosion, a process during which more noble, cathodic metals like stainless steel cause less noble, anodic metals like aluminum to be eaten away by corrosion as they lose electrons.

The process can occur anywhere that there is a galvanic circuit between the two dissimilar metals. It is greatly accelerated in the presence of salt water. As the name implies, the anodes, which are made of less noble metals like aluminum or zinc, sacrifice themselves to protect the least noble metal in the galvanic circuit.

Engine-cooling systems, sail drives, and prop-shafts are the most common applications where anodes are used on sailboats. Outboard engines also require anodes to protect their aluminum lower units. Because the anodes are eaten away in the process, boat owners must replace them on a regular basis, usually when the anodes mass is reduced to one-half of its original size.

Sacrificial anodes are relatively inexpensive, but the consequences of corrosion resulting from an ineffective or failed anode can be serious. More than one boat has sunk on its mooring due to a through-hull failure caused by galvanic corrosion. Although effective against typical galvanic corrosion, these zincs will not prevent the more potent stray current corrosion.

Although it is unlikely in a typical installation, you can have too much anodic protection. This is more common with miscalibrated impressed current systems, where a transformer is used to provide the potential, but too many or too reactive anodes can also have unintended consequences you should recognize.

Typically, you want a sacrificial zinc that has about about 1 to 2 percent the surface of the metal it is protecting. Usually, if you don’t see any warning signs of galvanic corrosion (pitting at the propellor, for example) you can assume your existing zinc is the correct size and replace like with like. However, if you have any concerns about the effectiveness of your protection system, you should have it checked. This is something you can hire a surveyor to do, but a competent do-it-yourselfer with the right tools can also confirm this with a high quality digital multimeter and a reference electrode. The makers of Fluke Multimeters offer a fairly straightforward guide on how to check your boats corrosion protection system.

The effects of overprotection on a fiberglass boat are usually not nearly as harmful as underprotection, but it is important to recognize the signs. On steel or wood hulls, over-protection can cause expensive damage if not caught in time. In any case, it is important to recognize the signs.

Burnback. It is a common sight to see a discolored ring 8-12 inches in diameter around a bronze seacock. Typically there will be increased growth, the result of paint that is no longer functioning. In every case we found, there were several things in common: the fittings were bonded, the paint was high-copper, and there were additional zincs, beyond the single shaft collar.

Based on a little testing, conversations with paint companies, and a little knowledge of chemistry, the cause is obvious; the same electron flow that is preventing copper and tin from leaving your bronze impellor has prevented copper ions from leaving the paint and repelling marine growth. There are various solutions that can be used alone or in combination with eachother: prime (several coats) all underwater metals before painting; reduce the number of anodes to achieve the desired voltage potential; switch to a less reactive anode material; switch to a copper-free paint; or switch to Marelon through hulls (reducing the amount of anodes required).

Paint delamination. This is most often seen on aluminum boats fitted with magnesium anodes, but it is sometimes seen on steel hulls with zinc anodes. If the driving potential is too great, gas is generated under the paint, and the paint is lifted off. For an aluminum boat, the answer is aluminum anodes alloyed for seawater plus proper painting procedures. For steel hulls it comes down to good hull preparation and priming, and careful regulation of the potential. We have seen recommendations between 0.75 and 0.9 volts (relative to a silver chloride reference electrode), and the U.S. Navy uses 0.85 volts as their design requirement for cathodic protection systems. Regular monitoring is advisable.

Caustic Wood Rot. If the driving potential is too great, bleach and caustic soda are produced around protected fittings. Since some of this reaction takes place inside the wood without seawater flush, the concentration of caustic will continue to rise and the caustic will begin to destroy the wood near the reaction site. Diagnosis is a simple matter of testing the pH of seepage or any powder near bonded fittings; if pH is greater than about 9.5, there is a problem. The solution is to limit bonding and zincs to the shaft/prop area. Less is more. A lower potential is typically recommended for wooden boats, about 0.5-0.6 volts.

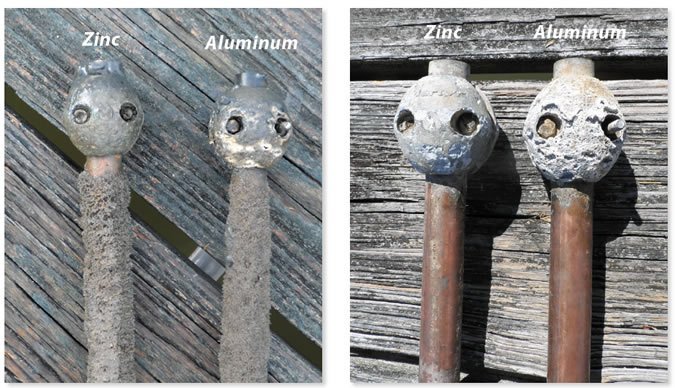

For our most recent anode testing results comparing aluminum vs. zinc anodes see the test report, “What’s the Best Anode Material?” For a more complete discussion on how to monitor galvanic corrosion, as well as advice on troubleshooting a wide range of marine electrical problems, the book Advanced Marine Electrics Troubleshooting by Practical Sailor contributor Ed Sherman is available at our online bookstore. All books sold through the bookstore help support our testing program.

THANKS for your article on too many zincs. 2 years ago I started seeing the zincs being totally eaten up after 12 months on my wooden schooner. I am now going through a 2 page check list I developed from Conrad Miller ” Your boat’s Electrical system” and Calder’s “Boat owner’s M&E manual” I am looking for problems from dock wiring and my own wiring errors. I did buy a portable zinc from West Marine connected to the schooner’s grounding system and hung it near the bronze prop

The link to the Fluke document points to a protected area and so serves up only an “Access Denied” xml block. It appears that the Fluke PDF can be found here:

www[.]frankshospitalworkshop[.]com/equipment/documents/workshop_equipment/background/Fluke%20-%20Testing%20Corrosion%20Protection%20Systems.pdf

and here:

pdf4pro[.]com/amp/view/testing-corrosion-protection-systems-fluke-259aef.html

(and a few other places).

After reading Fluke’s information sheet for testing the potential for electron flow with the use of a reference electrode, it leaves me wondering about where to source it. For a silver-silver chloride reference electrode the cost comparison is considerable, ranging from $16 from a supplier on Ebay to $140 from BoatZincs.com . I wonder, does the cheaper one only last for a few uses, or might it be less accurate? Also, Fluke does not specify whether the length of wire between the sea water and the multimeter is critical. It seems that if the test lead is inconveniently short, a copper-stranded wire might be added to make up the difference, if the connection is above water and the diameter of this wire is large enough to prevent any significant voltage drop. Can anyone enlighten me on these questions?