Tampa Bay, in some respects, is the new Taiwan of American boatbuilding. Lost in the miles of nondescript tin warehouses, surrounded by chain link fences, where hundreds of virtually anonymous businesses come and go like the rain, it is easy to become disillusioned: My yacht was built here?

Relic molds lie about the dirty industrial zones like whitewashed bones. Riggers become salesmen. Salesmen become builders. Builders never become businessmen, which is about the only difference between Taiwan and Tampa. An eager, low-paid workforce (read Cuban), favorable business climate (low taxes), and sunny weather (considered 50% of an employee’s compensation here) combine to make the environs of Florida’s largest west coast city a logical place to rent a shed, buy some used tooling, hire a couple of glass men and a carpenter (there’s a sort of floating labor pool in the Tampa area), and hang your shingle—I.M. Starstruck Yacht Co.

In the 1970s, Southern California—Costa Mesa more than any other city—was a major boatbuilding center. It was much the same as South Florida is today, until Orange County got tough on environmental emissions, and for the sake of a few parts per million of styrene fumes, essentially drove the boatbuilders out. Two early giants, Columbia Yachts and Jensen Marine (Cal boats) fled. Islander stuck it out until succumbing to bankruptcy just a few years ago.

Endeavour Yacht Corporation traces its lineage to those good ol’ days in Costa Mesa. Co-founder Rob Valdez began his career at Columbia, managed, incidentally, by brother Dick Valdez, who later founded Lancer Yachts. Rob followed Vince Lazzara to Florida to work for Gulfstar. The other co-founder, John Brooks, had worked for Charley Morgan and then Gulfstar and Irwin. “It’s so incestuous,” he once said, “it’s pathetic.”

In any case, Rob Valdez and John Brooks founded Endeavour in 1974 using the molds from Ted Irwin’s 32-footer to launch the business. The company built about 600 32s in all. Spurred by this success, Valdez and Brooks began looking around for a larger sistership to expand the line. Just how they “developed” the 37 is a tale best left untold until the principals pass away or become too senile to read the yachting periodicals. Brooks calls the 37 a “house design,” and that is generous. The total number of Endeavour 37s built is 476—a lot for a boat that size.

In 1986 Brooks sold the company to Coastal Financial Corporation of Denver, Colorado. Despite upgrading the pedigree of its model line with designs by Johan Valentijn, Endeavour’s position was plagued by declining sales and competition with its own products on the used boat market.

Brooks said, “When boats started to blister, I said, ‘God’s on our side! Maybe they’ll disappear and go away. Everything else becomes obsolete—your car, your clothes. We’re the only ones building a product that won’t go away!’ ”

The Endeavour 37 represents a decent value for the cruising family more interested in comfort and safety than breathtaking performance. Let’s take a closer look.

Sailing Performance

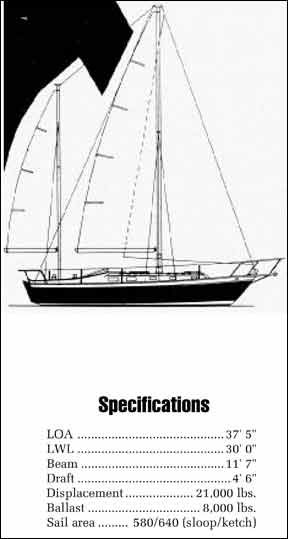

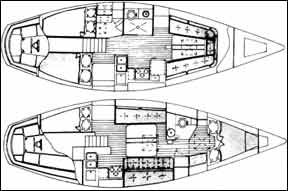

Most Endeavour 37s are sloop rigged, though the company did offer the ketch as an option—an extra $1,800 in 1977. The sloop is somewhat underpowered, so the ketch would appear to give the boat some much needed sail area. With either rig, it is not a fast boat, nor was it intended to be.

A bowsprit was added at one point to increase the foretriangle area and to facilitate handling ground tackle, though some photographs show the forestay still located at the stem despite the presence of an anchor platform, which was an earlier option. Also, a tall mast option was offered. Many readers complain of heavy weather helm in higher wind velocities, and moving the center of effort forward by means of enlarging the foretriangle would be one solution.

PHRF ratings range from a high of 198 for the standard rig in the Gulf of Mexico area, to 177 for a tall rig with bowsprit racing in Florida. PHRF ratings, of course, are adjusted according to local fleet performance, so variances between regions are to be expected. Most 37′ club racers rate 10 to 40 seconds per mile faster, and a high-performance boat such as the Elite 37 or J/37 will clean its clock by 80 seconds per mile and more. Make no mistake, the Endeavour is a cruising boat.

Some of the boat’s other troubles are presumably attributable to hull design, something most of us can do little about. The boat points no better, despite a fairly fine entry. One reader says he tacks through 115°, a number competitive only with schooners. Another notes excessive leeway.

Such performance may be expected from a boat with a long, shoal-draft keel, though it is cut away at the forefoot and terminates well forward of the spade rudder. Many owners report satisfactory balance as long as they pay attention to trim, reefing, and sail combinations. And it deserves mentioning that the Endeavour 37 has been happily employed as a charter boat by several companies, including Bahamas Yachting Services, which moves its fleet between the Bahamas and the Virgin Islands each season. It has and can make safe ocean passages.

Engine

The standard engine was the freshwater-cooled, 50-hp Perkins 4-108 with 2.5 to 1 reduction gear, a real workhorse that is something of a stick against which all others are measured. It rated tops among mechanics in Practical Sailor’s 1989 diesel engine survey. The company began phasing it out that year in favor of a new line. The Perkins 4-108 is a good engine for this boat, adequately sized for the waterline and displacement.

Access to the engine compartment is reasonable; the companionway steps are removable and there are sound insulating materials glued to the inside of the box.

Fuel capacity is about 65 gallons in a baffled tank.

A two-blade, bronze propeller was standard, though many respondents in our owner’s survey stated they had switched to a three-blade to improve control backing down. This, of course, is a problem with many boats. A three-blade, automatically feathering prop would improve performance under power and minimize drag under sail. It seems a shame to further destroy the performance of this boat by turning a three-blade, fixed prop, just for control in reverse; at that point one must ask himself just how much time he intends to spend going backwards.

Construction

The Endeavour 37 is a good example of low-tech construction—nothing fancy—no exotic fibers, core materials or unusual tooling. The hull is a singleskin, solid fiberglass laminate. No owners reported structural problems with oilcanning panels or moving bulkheads. Numerous owners, however, complained of gelcoat crazing, a condition also cited of the Endeavour 32. Gelcoat repair kits seldom match old and faded gelcoat colors, so owners are faced with an expensive re-gelcoat job or painting with an epoxy or polyurethane paint system. Since most older fiberglass boats inevitably suffer gelcoat crazing in areas of stress or impact (a dropped winch handle will do it), we’d be more concerned with the condition of gelcoat below the waterline. The results of Practical Sailor’s 1989 Boat Owner’s Questionnaire showed 8 of 19 Endeavours had blistered; 42% is high.

The interior is built up of plywood with teak trim. Workmanship is generally good. In fact, one owner who said his hobby is woodworking, said, “The trim joints are excellent.” In general, owners liked the boat because it feels solid, “built like a tank.”

Problem areas included gate valves on throughhulls, which some owners have correctly replaced with sea cocks; side-loading refrigerators on some boats that were replaced with top-loading ice boxes; pumping of the Isomat spar; inaccessible electrical wiring; V-berths too short for people over 6′; listing due to water and holding tank placement; and plastic Vetus hatches crazing and dripping. Ventilation seems to be a concern of many owners, though with 10 opening portlights and three hatches, there’s not much more to be done except add cabin fans and rig wind scoops.

An Endeavour trademark is the teak parquet cabin sole, which makes you feel like you’re dribbling down center court at the Boston Garden. Some like it, some don’t, but at least it’s different.

The keel is part of the hull mold, with internal lead ballast dropped in and glassed over. There are no keel bolts to worry about, but in the event of a grounding one should look to see if the skin has been punctured and water entered the cavity. The laminate must be thoroughly dried before repairs are made, and this can mean a fairly long waiting period. The shape of the keel is what is sometimes called a “cruising fin,” shallow and long with a straight run. The boat should take the bottom well, whether it is an accidental grounding or intentional careening for bottom work on some distant island.

Interior

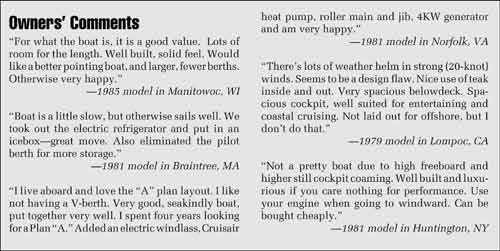

Two arrangement plans were offered—“A” and “B.” The first is a bit unusual in that the forward V-berths are dispensed with in favor of an enormous Ushaped dinette; owners of this plan like it. In its lowered position, the table converts to a huge, sumptuous double berth.

And there is a handy shelf forward for books, television and knick-knacks. The hull sides are decorated with thin teak slats that are widely spaced and fastened flat against the liner. This plan has a large forepeak, divided into two compartments, one for chain and the after one for sails, accessible from the deck.

The galley is a sideboard affair located to starboard and the head is opposite to port, just about midships. Hot and cold pressure water and a shower are standard equipment. The sink is porcelain and there is a full-length mirror. Plumbing has copper tubing and there is an automatic shower sump pump. Aft in Plan “A” are two large double quarter berths.

Plan “B” is the more conventional, with V-berths forward (no sail stowage in the forepeak), the toilet compartment just abaft the head of the bunk, settees in the saloon with an offset dropleaf table, pilot berth outboard above the starboard settee, aft galley and a port quarter cabin.

There is a privacy door to this stateroom (not shown in the layout illustration), which is no doubt what the public demands; however, some owners complain that it is stuffy and cramped. That, of course, is what you get with a small, enclosed cabin aft in the boat; despite overhead hatches, vents, and portlight opening into the cockpit footwell, ventilation is bound to suffer.

There seem to be pros and cons to both plans. “A” is certainly more open, which will suit a couple with few overnight guests. Ventilation is better as air coming in through the forward deck hatch freely circulates in the main cabin; the main bulkhead in “B,” as in most boats with this type of layout, obstructs air flow, and nowhere is this problem more acute than in the tropics, where every breath of ocean breeze feels like the difference between life and death.

Both plans offer sleeping accommodations for at least six, including decent sea berths. Plan “B” has a pilot berth that ups the count to seven, but most owners of this layout had converted it to stowage space.

The deep, double sinks in both “A” and “B” are reasonably close to the centerline of the boat, and should drain on either tack.

In the late 70s, a three-burner alcohol stove and oven was standard. On the boat we chartered for a week in the Bahama Islands, the stove was LPG and there was a nifty tank locker in the cockpit coaming, well hidden yet easily accessed. The garbage container and insulated beverage container in the cockpit are nice features.

Both plans also have chart tables, which of course is appreciated. The longer you study the arrangement plans, the more you realize just how much has been fitted into the available space. If any corners have been cut to make this happen it’s probably the length of some berths, which a few owners criticized (presumably the endomorphs and Ichabod Cranes among us).

A high percentage of the owners surveyed are liveaboards and almost without exception they consider the boat ideal for their purposes. And it’s not difficult to see why. During our week of chartering, there was plenty of space for two couples to move about without knocking elbows at every turn.

The aft cabin is, however, cramped, and getting into the high berth would be easier with a step; one is leery of jumping in, especially given the low overheads of boats. Also, one has to get his bottom on the berth first, then swivel around to get the feet aimed in the right direction. If your mate is already in bed, this can be a maneuver almost impossible to perform politely! The V-berths are preferred for ventilation and ease of getting in and out.

On Deck

The Endeavour 37 is easily appreciated on deck. The side decks are wide and uncluttered. The foredeck, though narrow at the bow, is adequate for sail handling, and the high cockpit coaming makes for a good backrest and a sense of protection. The toerail rises forward so that there is a sort of mini-bulwark for security when changing sails or handling ground tackle.

In profile, the coaming seems too high, especially on top of the high freeboard; one owner said he’d have liked to see an Endeavour 37 without this great, wraparound coaming.

From the helm it’s a different story. The varnished cap board on the coaming defines the attractive curve, and does impart a feeling of safety and well being.

Coamings such as this, which extend over the sea hood (a good safety feature), make installation of a waterproof dodger much easier, though the dodger will be large and extend athwartship nearly the full beam of the boat at that station.

The large size of the cockpit is worth noting. In fact, it probably borders on being too large for offshore sailing. A pooping may temporarily affect handling, but given the considerable volume of the hull, the presence of a good bridgedeck, and assuming that weather boards are in place, water shouldn’t get below or unduly sink the stern. Still, it is a boat we’d like to see with large diameter scuppers for safety’s sake. One owner said he thought it was possible to run two large scupper hoses aft through the transom, which is a sensible idea. Another said the cockpit was too wide and that it was difficult to brace his feet when heeled.

Conclusion

The Endeavour 37 is a Florida boat. Windward sailing performance was purposely sacrificed for shoal draft, which is a requirement of cruising the Florida Keys and Bahama Islands. The cockpit is large and the deck area spacious.

Either you like the Endeavour 37’s distinctive cockpit coaming or you don’t; we found the cabintop area just abaft the coaming useful for stowing suntan lotion, hats and the usual cockpit clutter; in calm conditions, it even makes a fairly decent, elevated seat when you want to pontificate to the rest of the crew.

Sailing performance is marginal, especially upwind. The rig, however, is very simple and will seldom get the beginner in trouble, which explains the boat’s appeal to charter companies. A light, nylon multi-purpose sail will be essential to light air performance, but it is probable that many owners turn on the engine when the wind drops below about 10 knots, and when going to windward to get that extra few degrees.

Our most serious concerns with the boat are, unfortunately, those that are uncorrectable. You can replace the gate valves with sea cocks, rewire the electrical system, even install flexible water and holding tanks to correct minor listing tendencies, but there’s nothing practical that can be done about poor hull design.

One reader suggested fitting a hollow keel shoe to improve the boat’s windward performance…hollow, he said, because the boat is heavy enough as it is. The boat also appears not to balance well, and though this tendency can be mitigated to some extent by mast rake and sail trim, it may well extend to the shape of the ends of the hull’s waterline plane when heeled.

In all fairness, however, the Endeavour 37 is heavily built, reasonably well finished, comfortable to cruise and live aboard, and it sells for an attractive price.