You have probably heard people say sailing solo is dangerous or irresponsible. How can you keep a proper watch? What happens if you have an accident? You may have heard stories of people going crazy due to isolation on long solo voyages. Sailing is all about freedom, and I am not going to tell you not to try sailing solo. Nor will I tell you that it is reckless and irresponsible. You are the skipper and one of the great things about sailing is that, as a skipper, you are free to choose, long may that last!

What I want to talk about is how to go about sailing solo safely, and some of the things I like about it. Solo simply means being on your own when the boat is underway. But, just like crewed boats, the passage matters! A solo ocean crossing is something that should make anyone think carefully, but a 10-mile hop between islands might sound hardly worth the title of solo sailing (believe me, it is!).

So, what is the difference between a solo and a crewed passage? The first thing most people think of is “How do you keep a proper watch”. That is an issue, but with modern electronics a lot less than it used to be, and it is not where I would start the discussion when considering a solo sail. Here is my list, in order of importance. A lot of these items are about the boat and how it is set up. We’ll get to the capabilities of the skipper in part 2 in next week’s Wednesday installment of Practical Sailor.

First point. If the answer is “no” to this question, go straight back to harbor and don’t even think about solo sailing. IS MY AUTOPILOT BOMB PROOF, AND AM I ABLE TO STEER THE BOAT WITHOUT TOUCHING THE HELM IN ANY SEA CONDITIONS? No? Stop and fix it. Yes? Continue to the next question.

The second point. AM I ABLE TO STAY ABOARD THE BOAT UNDER ANY AND ALL CIRCUMSTANCES? If you are sailing solo, falling overboard is almost certainly fatal for obvious reasons. A bit less obvious is that going over the rail, even if you are wearing a harness attached to a tether that’s clipped to a jackline, is almost as bad. In any boat with more than 3-feet of freeboard, you are very unlikely to get back aboard while being dragged at any speed. So, you absolutely MUST NOT go over the rail. I am not going to go into detail on this because there is also an article coming on how to rig a centerline jackline for clipping in, and why, in my opinion, I think running them along the side decks is a bad idea. Stay tuned for that.

The third point: If you plan on solo sailing, how will you cope with your boat and the environment? Think about some of these not-so-simple questions.

- How will I cope with a sudden heavy squall at night?

- How will I cope with prolonged heavy weather?

- How am I going to moor, anchor, or heave-to?

- How will I cope with normal activities of living like cooking, showering and sleeping?

- How will I manage watchkeeping?

- What will happen if something on the boat breaks?

The fourth point: Things related to me, my person, and how I will cope while sailing solo.

- What happens if I have an accident or get sick, including seasick?

- How will I cope psychologically with being on my own?

- How self-reliant am I?

- How do I function if I am short of sleep or having very irregular sleep patterns?

- How is my mental health and will I recognize if I am having issues?

If you run down that list and can answer all the questions properly, you are probably already a solo sailor! If you have never sailed solo and you aren’t sure if you can answer those questions affirmatively, I would respectfully suggest you may be in for some surprises. It doesn’t mean you can’t work up to becoming a solo sailor. But you’ll have to train, which in itself can be very rewarding.

HOW TO APPROACH SOLO SAILING SAFELY

While not everyone is cut out for solo sailing, I would say that any reasonably experienced skipper should be capable of a solo passage, but that does not mean they will necessarily enjoy it. Equally important…not every boat is suitable for sailing solo.

Just before going on to talk about how we cope as a solo sailor, it is worth talking a bit about the type of boat what makes a good solo sailboat. This may be controversial, but I much prefer more traditional heavyweight long keel boats for solo sailing. (See the Bristol Channel Cutter in our lead photo: a staysail rig with a full keel. Boats of the type have made solo circumnavigations.) They may be slower, and that limits range when coastal hopping, but they generally need much less crew input and heave to more reliably. They respond more slowly, which can give you more time to do things. Also, the motion in a seaway is generally easier and they track really well so need less input from the autopilot. I am not saying that no fin-keel boat will heave to or that a lightweight, fine-entry broad-stern, canoe-bodied boat can’t be sailed solo. Obviously, it can. You only have to look at solo ocean racing to see that. What I am saying is that these boats can demand a lot more from the crew. If you are a young, fit, and expert sailor you may find that exciting and enjoy the challenge. But if you are older, less fit, or less experienced you need to ask “not what I can do for the boat but what the boat can do for me” to misquote a famous US president.

It’s also important to really get used to the boat before you commit. Next time there is a forecast above 25 knots, go out and see how she goes, practice heaving to, and reefing to see how the autopilot reacts. Take crew with you but make them sit on their hands! They are there to bail you out if things don’t work out. Even better, find someone who is also interested in solo sailing and take turns. Watching how someone else copes can be a good way of working out and improving your strategies.

BRASS TACKS

So, let’s go through those lists and see both what’s involved and why I think they are important.

First, coping with squalls. Any passage longer than nipping across a bay means you could encounter a squall. The worst case is it hits at night while you are taking a nap, so you don’t see it coming and suddenly the boat is overpowered and standing on her ear. You may answer, “No problem. I’ll just put a few rolls in the jib, and I can reef the main from the cockpit, done it lots of times.”

Have you really? When the lee deck is awash, the rudder is more or less out of the water, and the boat is on autopilot? If you can reef in moderate conditions in 5 minutes, I am prepared to bet that span of time will double at night, double again in heavy weather, and double again if recovering from being overpowered. What normally takes five minutes or less with crew on a nice day can easily take 30 minutes to an hour at night when overpowered and, equally important, you are exhausted. Then what happens when the next one hits?

This is the first lesson in solo sailing. What works on a crewed boat may be the wrong strategy sailing solo. If it takes an hour to get the boat back under control, the likelihood that something will blow out is high. A flogging sail in 30-40 knots is likely to rip or damage deck fittings.

The key in solo sailing is always to prioritize looking after the crew, nobody is coming on to relieve you!! Then looking after the boat. What would I do in the squall situation described? Heave-to or furl/drop the head sail, or heave-to under motor. Both will get the boat back under control quickly, then you can work out what sail to set when conditions moderate. Often you can just ride out the squall hove too and then get back underway.

A BIGGER, LONGER BLOW

Prolonged heavy weather is not most skippers’ favorite condition, but it’s especially disagreeable when solo. Have you steered a boat in heavy weather? For how long? The answer is in hours not days.

You have to set the boat up so that you can go below and leave her to it. You will still come on deck at decent intervals, make adjustments, and check for chafe, but you have to be able to go below and get some rest, food and drink. So, you need to know how your boat will respond in difficult seas when under autopilot. A lot of this is about getting the sail trim right. Reducing sail by one more reef than you would with crew makes a big difference. The boat rides easier and there is less stress on the autopilot. Equally important is having efficient sails. Most boats sail reasonably efficiently under full canvas but not always when sail is reduced. If you have a 2-sail rig with a furling headsail, as you reef, the center of effort of both sails moves forward. The headsail also tends to become deeper, not flatter. This effectively puts the power generated by the sails forward of the keel and increases drag from the headsail. Both of these tend to create lee helm, which the autopilot has to fight. Either it is going to be overwhelmed and not able to steer a steady course or, if it is powerful enough, it’s going to use a lot of electrical power. This can easily be more than 100Ah in a 35-foot boat, and double that in anything over 40 feet. This is one of the reasons cutter rigs are so good for solo sailors. Furl the jib and sail on reefed main and staysail and the boat will stay far more balanced. If you have a 2-sail rig and want to do any significant solo sailing, I would definitely suggest thinking about adding a removable staysail. Incidentally, if you have 2 headsails, but they are rigged very close, you’ve got a great situation, especially downwind. But I would still classify this as a 2-sail rig because the center of effort still stays forward when you change to the inside sail. In a true cutter with a staysail, it moves back several feet, which has a balancing effect.

The ability to heave to is, in my view, essential for solo sailing. Prolonged heavy weather especially with the wind forward is very tiring and makes simple jobs more difficult. Being able to heave to and get some decent sleep, make a meal, or just sort the boat out can make a huge difference in how you cope. Yes, it loses some mileage, but you will sail better for the break and probably make it up. Sailing solo on anything beyond a daylight coastal passage I want a boat that will heave-to without a worry in 35-40 knots. I am not talking about storm tactics here, just the need to take a break and manage the boat when it is rough.

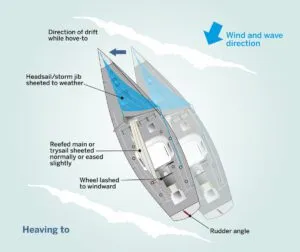

The boat should come to a stop and sit quietly. In lighter air, consider jibing into a hove-to configuration, headsail aback, tiller or wheel hard over in the opposite direction. With the headsail backed, the bow wants to bear off, but the tiller keeps the bow up closer to the wind, effectively locking the boat in a stable slide to leeward. You can go below to rest, restore and keep watch with radar, AIS on your VHF, or GPS with traffic proximity alarms. You’ll want to come on deck occasionally to check the sheets for chafe. Every boat is different, and how your boat heaves-to will depend on the keel configuration and windage. For example, a stern arch, Bimini or doghouse creates more windage aft, a high bow would do the opposite. A full or long keel will generally be very stable, whereas a short fin keel will allow the boat to yaw around a lot more. What you are looking for is to keep the bow between about 30deg and 50deg off the wind. If the boat yaws too high, you risk her tacking, too low and she is going to roll a lot more and risk being laid over if it gets rough. You can set the angle she lays by adjusting the amount of sail. If she points too high, reef the main. If too low, furl some canvas or switch to a smaller headsail. I like a hanked-on staysail for these situations. The other thing to look for is how much leeway you make. Some leeway is good, the boat is effectively sliding sideways through the water, and it will lay a slick upwind that will tend to stop waves breaking. If she makes excessive leeway, you might risk running short of sea room. You can adjust the leeway by increasing or reducing sail. The other point about how much sail to set is that enough canvas will pin the boat down and make her ride steadily at about 15deg of heel. Too much is uncomfortable and strains gear, too little and the boat will get more lively and yaw more. Start in moderate winds and progress until you know your boat’s best setup for all conditions, and you will have gained an excellent addition to your sailing repertoire.

WATCHKEEPING

Are you surprised that watchkeeping is so far down the list? Actually, 20 years ago it would have been higher, but this is an area where technology has really made a difference. When I am below in my bunk I can see the AIS transponder screen, radar, chart plotter, log and wind speed/direction without getting out of my bunk. In most conditions this is as effective as a deck watch. I can also set alarms on both the AIS and Radar that will wake me if another vessel approaches. The old routine of setting a timer and sticking your head out of the hatch to scan the horizon every 10 minutes was very hard on the body and meant you got no good sleep.

With good modern electronics and alarms, you at least don’t have to get out of your bunk each time. It is still a good idea to get some decent periods of sleep during the day rather than at night. AIS is brilliant for big ships both to let you know they are there and so that they see that you are a sailboat well in advance. Since fitting it I have never been in close quarters with shipping and have watched many make 2-5deg course changes 10 miles out to give me clearance. Unfortunately, in many areas small vessels don’t have transponders which is why you need radar as well. It needs to be a decent one, personally I have never seen a 12 -inch array that worked well enough. Good to see a headland in fog, but not to plot the course and direction of a fishing boat. Small radars also seem to be less good at cutting through wave and rain clutter. Ideally, I would say a 4 kW 24-inch array is what you want, but a good 18-inch may work. It also needs to be high enough to see over the waves, so it wants to be on the mast, not the stern arch. For solo sailing the primary role of radar is to reliably alert you to small vessels at a range of at least 5 miles in rough going. The other point about watch-keeping is that it really depends on where you are.

I remember sailing solo from the Bristol Channel in England to N/W Spain. For the first 36 hours I stayed on deck napping on the cockpit bench and living on instant snacks. Once I cleared the continental shelf, I did not see another vessel until I was 50 miles off the Spanish coast. Most people crossing oceans report the same. Once you clear the coastal traffic zone, it’s considered busy if you see more than one ship every 1000 miles. If you doubt this, take a look at the AIS tracking apps on the internet and you will see that about 95% of all shipping is coastal. The downside to this

is that this kit is expensive! You will finish up with the level of equipment normally seen on round-the-world passage makers but for solo sailing it becomes even more important for coastal passages that last longer than about 12 hours. My strategy is to either plan to hop between marinas and anchorages doing no more than 50 miles per day (often half that) or head out beyond the coastal zone and make my mileage out there if I am going to a new cruising ground. Incidentally, I have never seen anything that can see pot buoys; no metal in them. If there are pot buoys around, we are back to the mark 1 eyeball!!

MOORING AND DOCKING

Your solo voyage is done and you’re back in the harbor. Most skippers find this stressful even with crew. Solo it can be a nightmare. My ideal setup for anchoring is a remote control for the windlass so I can operate it from the cockpit while still being able to work the engine controls and see the depth sounder. The other essential is a chain locker with a deep enough drop so that the chain is self-stowing. If you have to either go to the fore deck or worse, go below, to knock the chain pile down that is a recipe for major problems while solo anchoring in a tight harbor.

When mooring, fit a centre cleat and learn to use it! When you come alongside in a marina or dock, start early. You will have enough to do maneuvering the boat and will not have time to set up fenders and lines as you approach the berth like you would with crew. In a strange harbour tell them you are solo, and they may have someone who can take a line for you. If you are not sure which side you will be on, always set up both. I have found the key to solo docking is to drop a line from a center cleat amidships that will become an after-spring line. Drop a spliced loop from this line onto a dock bollard, and as it comes tight put the stern into the dock with the rudder and leave the engine in slow ahead. The boat will lay solidly alongside while you sort out the rest of the lines. You may need to adjust the cleat position to get it to work well.

Unfortunately, this only works if the dock has cleats or bollards. In North America a lot of marinas use rails to tie up to so you will have to come to a stop alongside and jump off to set up the midship line. You can then get back on board and motor ahead against it to keep her in place while you set up the other lines. The big risk is that if you come alongside with a crosswind off the dock and start with a bow or stern line by the time you have that set up the other end has blown off and you risk swinging into the boat next to you or across the finger. I also find it useful to have a couple of long floating lines on board. Especially if it is windy. Warping the boat in and out of a tight space can give you much more control than the engine alone but that is another article! Good close quarters maneuvering is an important skill for any solo sailor, but it is much easier to learn by doing than from a book. If this is an area where you are not very confident it might be worth booking a lesson with the local sailing school. Tell them you are solo when you book as it is significantly different from the same maneuvers with crew and not something all instructors will be comfortable with.

LOOKING AFTER YOURSELF

In my healthcare profession we call this “activities of daily living”. It refers to what you need to do to stay alert and efficient. Food, sleep, personal hygiene and maintaining a livable environment are the essentials. When you sail with crew this is what you do when off-watch, but solo you have to fit it in while also running the boat. Everyone is different and every boat is different so you are going to have to develop a plan that works for you, and you can only do that by gradually building up experience. I have a goal (which I don’t always reach) that when I get into harbour the boat should just need provisioning before the next trip. If you fall into your bunk for a 10-hour sleep and then spend the next day sorting the boat out, work out why and how to do better next time! It is often the little things that count, improving stowage, sailing more conservatively, heaving to for breaks when you need to, and maintaining a good nutritious diet are all key ingredients. Just generally improving the efficiency of sail management and moving around the boat can also make a big difference. The KIS (keep it simple) principle is a good one to apply here.

BREAKAGES

Breakages. The old adage about the sea being able to break anything is true whether you are solo or have crew. Because solo sailors tend to run the boat a bit more conservatively, it does actually reduce the chance of breakages a bit, but they still happen. The main issue is that you are on you own when fixing stuff and still need to run the ship with the other hand. This raises 2 important questions. First, how much does stuff weigh? You may be able to control a large head sail with a power winch but if it tears and you need to take it down to stitch it, can you physically get it down and back to the cockpit for repairs? There is a tendency these days for people to go for bigger boats because they are more comfortable. Often true, but if that means the gear is too heavy for you to manhandle in the event of a breakage, it could leave you stuck. Even if you can make it back to harbour it could still mean the difference between doing the work yourself or paying a yard $100/hr to do it for you! The second issue: what are you going to do about jobs that need 2 people? Ever tried removing a sail track on your own? Not possible. You need someone topside with a screwdriver and someone belowdecks with a spanner (a wrench in American). So go through the boat and look at what you can and cannot repair on your own, and then make a plan of what you are going to do if you can’t make repairs to essential gear on your own. Another win for having more than 2 sails and simple systems. I prefer to keep staysails hanked on and would not go for anything but slab reefing on the main just for this reason. Less to break.

We’ve covered boat handling. In part 2 of this study of solo sailing we’ll talk about how to manage a critical piece of equipment—the skipper.

Good article! A few thoughts:

Based on PS testing and cruiser experiences, the original Gibb hooks were very good, ahead of their time, but the thin stamped hooks from Spinlock and others should have been recalled. They do not meet industry standards and are not safe when twisted or side loaded. They can fail under body weight, with fatal results … which has happened.

Docking single handed can be a real trial. One of the most important traits of a singlehander is to know his limits, and in that vein, I have often chosen to anchor out if the combination of wind and tide seemed too risky. How quickly can you move about the boat if things go a little sideways? It’s not worth damaging someone else’s boat, for example, and I can probably move into that slip tomorrow, when the weather moderates, or maybe just after the tide changes. Another alternative can be to request a different slip that is more manageable, for example, an easily accessed bulkhead, or a more protected area of the marina.

For me, the central theme is breaking everything down into simple, one person jobs. It may take longer, so allow more time.

Looking forward to the next installment!

Great article and agree with most of your points.

Great little article. Thanks.

Another good, useful article from PS, thanks Roland.

I appreciate seeing someone burst into print who obviously knows his subject; its all too common these days to see people being completely clueless, and seemingly proud of it!

I look forward to Part 2!

Great article! I’ve done a lot of solo sailing on my 40′ sloop; lots of 6 to 12 hour passages and several two day-ish passages of roughly 250 nm. They’ve generally gone well but your article has shown me how luck may have played a bigger role than I knew! Lots of good stuff here for me to incorporate. Thanks much!

Excellent advice here for the solo sailor. Funny how often the first or last 10 ft of a solo trip is often the most stressful – getting on or off the dock single-handed. Duncan Wells has some good photo-essays on this in his Stress-free Sailing. I also remember asking a very accomplished solo racer how he managed his spinnaker sets alone on long-distance courses. “Sometimes better than others” he admitted. “But if I screw up who cares I just fix it – it’s not like there are a whole bunch of people watching me !”

Provided the tidal stream and wind are not excessive I am happy to bring my 29′ yacht solo into a pontoon finger berth. I can even cope with a not too strong wind blowing me off quite a short pontoon. However, what I need is a cleat on the pontoon in an appropriate position for my mid-ship line. If such a cleat is present it is usually positioned in the middle of the short finger pontoon, where it is of no use to me when coming alongside. I need it about 1 to 1.5 metre from the outer end of the finger pontoon. Do you wish me to explain why with diagrams ? I have had discussions with marina managers, but they insist on putting such a cleat in the middle of the finger pontoon. Some marinas have kindly said that I can always call for assistance if I cannot cope. Given the right equipment I can usually cope, even after dark, when marina staff are often not available. Also, in France, marina staff are not always available at lunch-time, and often there is a “hoop” rather than a cleat at the outer end of the finger pontoon.

When sailing solo I can do most things that a full-crewed yacht can do, but it will take me longer, and (of course) I cannot be at both ends of the yacht at the same time! The secret is planning. When hoping for a marina berth, I will not enter the marina unless I know three things:- my berth location (e.g. K17); which side of the pontoon to enter (e.g. between J and K, or between K and L); and which side of my boat to expect the pontoon (assuming I go in bow first). The first requirement is obvious, the second is because I do not wish to have to turn my boat around before meeting a dead-end, and the third is because I put fenders low for a pontoon, but high when expecting another boat on that side of my boat. Since I am solo, I have 11 fenders, which take some time to distribute. I do not wish to leave the helm when in a marina in order to set or adjust them. So, when calling for a berth on VHF before entering the marina, if I am told just to follow the ‘follow-me’ dinghy, I will say “No, tell me more…” ! And, if I am just given K17 as my berth, I will be taking up further VHF time. I do not wish to be difficult. I call it planning.

Thanks for this well written article. I’m looking forward to part 2.

I have not done any solo sailing on my Baltic 51 but did do a double handed return from Bermuda to Newport 2 years ago. We had an autopilot failure which was not fun. Even two people steering for 5 days was a challenge. The boat could balance and the wheel locked for a few minutes but not long enough to take a nap. If I was solo, heaving too for sleeping would have been the only option. We didn’t try to rig “sheet to tiller” type of steering with the wheel. Probably should have tried. If I was going solo, I’d want a totally redundant system.

Great article, Thanks. I always use the midship line method you describe when docking our 56′ ketch solo or with inexperienced crew. (Also called the “magic spring line” in some Youtube videos) Saved many a potential accident in current and crosswind prone marinas. In addition to deploying the fenders and positioning the dock lines we do one extra step that can be very helpful before pulling into the marina. For the midship line that is first to be deployed we use two strips of masking tape to tape the open loop end of the line to the end of a long boat hook. The loop then can be easily draped over the cleat from the deck of the boat without leaving the boat. This way no heroic leaps are needed to the dock and it works if the boat is being blown or misses the dock by up to 8′. We use a big 2′ diameter loop on the end of a 8′ pole, not just the standard spliced dock line loop. Once the loop is over the cleat or bollard, a quick yank rips the tape and leaves the line secure. Then motor forward slowly till the midship line goes taught, generally steering away form the dock, let it gently and slowly pull the boat into the dock then step of and secure the rest of the lines, generally starting with the rear line first.

This works great on docks with cleats near the end of the fingers. Docks with wooden or metal rails only are trickier and require hopping off the boat onto the dock with a much longer midship line to use the same technique. Tricky when solo unless it is very calm and you tie the midship line very quicky. I am considering fabricating a midship line grapple type hook on a pole that might work to hook over rails. A work in progress.

I got a comment from Grant Calverley via Email who raises a good question about what to do if coming alongside a wharf or finger with rail to tie to instead of cleats. How do you attach a midship line? I agree that for the solo sailor they are a pain and common in N America. I have not found a solution so If anyone has any ideas that they find work please let me know and I will get them published.

Your first point is so important, and on that note NO cruising sailboat that is sailed solo (or with a couple for that matter) should leave on a passage without a windvane. IMHO no short handed boat should rely on electric auto pilots. Next, a comfortable place to sleep in the cockpit is critical. I just do not agree with relying on electronic aids for watchkeeping. I take short cat naps at night in the cockpit and can easily sit up and look for lights, and my long sleeps are during the day in good visibility where I am more likely to be seen. A beanbag is really good for cat naps in the cockpit in bad weather as you can settle into place. Next is meal prep. Have a system to account for weather. I have several wide mouth thermos to make several small hot meals. Easy to just put in pan and reheat if needed. You mention heaving to several times. Yes, absolutely. But lets take it a step further. Just be comfortable staying at sea. Never force your way in to a landfall because you are alone and tired. Learn how to really heave to and get used to it. Use the bean bag. Trust your boat, relax, eat your pre prepped meals and chill out. Last is stay hydrated!!!