“Big High, Blue Sky, Goodbye…” All you need to get started, right?

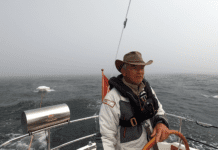

…Not so fast. Heed another quote from Captain Ron, hero of the 1992 sailing misadventure movie: “Anything’s gonna happen, it’s gonna happen out there…” That’s the truth of it. The test of the sea challenges human and machine, and the Gulf Stream is more than happy to test the hundreds of vessels plying its waters every day.

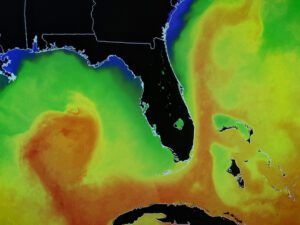

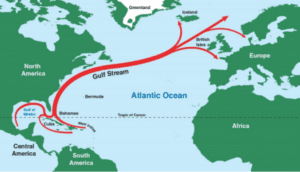

The realm of the Gulf Stream spans the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, and the North Atlantic Ocean starting along the shorelines of the Gulf States, stretching north along the US eastern Seaboard and Atlantic Canada before heading for Europe. The NOAA National Ocean Service rates the average speed of the Gulf Stream at 6.4 Km/h or 4 mph – fastest nearer the surface. Water temperature ranges from 7- to 22-degrees Celsius, a peak temperature not too far off the prerequisite minimum ocean temperature of 26 degrees Celsius when it’s hurricane feeding time.

The Stream arcs around its namesake the Gulf of Mexico. This substantial body of water is an irregular bowl-shaped feature that is shallower at its perimeter and deepest towards the center, where we find the Sigsbee abyssal deep at more than 14,000 feet. The Gulf’s average depth comes in at approximately 5,000 feet—an important point when considering potential wave profiles as the Stream dances along the upper canyons of the bowl.

The Stream transports a volume of water greater than all the world’s rivers combined. (Data courtesy NOAA National Ocean Service). Thus, it greatly influences climate and sea state along its entire track, , especially Florida, where it flows on three sides. These warm waters help heat the air above it, as the ocean-absorbed shortwave solar radiation is slowly released as longwave radiation. This is significant for wind, wave, and storm development.

Should cold air from the Great Plains escape south, this air mass over the warmer flow will generate significant convective cloud development.

THE MARINER’S WEATHER CHECKLIST

Like any airline captain, the very first order of business for a mariner is to check the current weather and forecast, monitor the weather broadcast frequencies to note trends – and find the reported and charted wind now and modelled into the future. Compare different models to make a go, no-go determination. Importantly, the competent mariner must make an informed weather decision while you still have a choice. As pilots like to tell each other: “Better to be down here wishing you were up there, than to be up there wishing you were down here.” The same holds amply true for sailors. How many of us have regretted shoving off into iffy weather that only gets worse?

If your decision is a go, one of the first things you’ll notice out there is surface wind velocity increasing away from shore as friction is reduced. A strong wind in the harbor is likely a gale force at sea. Waves will behave differently as depth increases and the rebound effects of a shoreline diminish. Nevertheless, mature cumulonimbus, vertical cloud development anatomy, and circulation can be beastly, with a continuum of lifecycles as long as destabilizing dynamic forces persist.

Thunderstorms can behave similarly over the fetch of the Gulf as they do over the fetch of Kansas’s plains – spawning waterspouts that are equally as dangerous as tornados. Sea-borne storm chasing will range from slow motion excitement at a distance, to terrifying danger if you find yourself being pursued by one of these things. Being in the vicinity or under the wrong part of that cloud can subject you and your vessel to extremes that, besides waterspouts, can include lightning strikes, heavy precipitation, and localized high winds, including intense microbursts.

A GULF STREAM MINDSET

If you’re going to go anywhere near the Gulf Stream—and if you’re sailing on the eastern seaboard there is no escaping its influence— remember that timing is everything; we don’t voluntarily hang around hurricane-season waters without awareness of tropical depressions hundreds of miles away. Testament to this is October 29th, 2012 with the loss of the HMS Bounty replica off North Carolina during Super Storm Sandy.

This awareness begins with knowledge of weather – sea and sky –and updating this knowledge daily before venturing out beyond the safety of harbor. (Even in harbor you have to be on your game if a hurricane is forecast and you want to save your boat.) Even so, and truly astonishing, was the tornado turned waterspout turned tornado of Jan. 6th, 2024, which ruined the peaceful night for at least one Fort Lauderdale catamaran anchored in safe harbor. The tough lesson that day? Dangers lurk even in the hurricane off-season – and even if insurance policies say it is okay to come out and play.

In 1968, Sir Robin Knox-Johnston sailed Suhaili around the globe with a Guinness barroom barometer, a tin clock and a sextant. The radio failed not long after departure. But Robin had one thing going for him that surpassed his questionable equipment. Experience.

In a 2020 documentary titled, “Sir Robin Knox-Johnston: Sailing Legend | Clipper Round the World Race3,” Sir Robin and his fellow competitors pressed for a delayed start of the first Sunday-Times Golden Globe around the world race in 1968. Originally planned for a risky October departure, Robin and friends successfully changed the rules of engagement. Their collective superior knowledge of seasonal weather patterns and awareness of weather-windows changed how the race was to be conducted, ensuring a safe departure for all. How can you follow Sir Robin’s example?

THINK LIKE ROBIN

Every time you get ready to depart your anchorage and head out to sea—be it for a short-jaunt day sail, a multi-night Gulf Stream run, or a multi-month Great Loop circuit— know the weather; know your limits – and remind yourself it’s okay to delay. Delay means sound nautical decision-making.

I want to take a page or two out of my aviation weather background and apply it to planning your sail and sailing your sail-plan. This presses my editor for word count; at the same time, I believe it is important to at least touch on it while we talk weather. I realize there are many ways to approach the pre-sail weather planning and just as many ways each of you, as responsible captains, have developed as your best practice both for departure and once underway. We all have our routines.

Comparatively speaking, aviation is brutally unforgiving of carelessness, incapacity, or neglect – unlike a road trip, where you can pull over and call the auto club. Similarly, sailing can be equally brutal; better perhaps only in that the US Coast Guard (USCG) is always on duty – well trained & well equipped to assist. When you’re in dire straits, search and rescue (SAR) are only a mayday away. Also, there are auto-club-like assistance available near ports with these services (it’s a good idea to subscribe to either Tow Boat US or Sea Tow). These are not replacements for thorough planning. Even so, it’s comforting to know they are there. A quote from the late Col. Frank Borman (1928-2023) U.S. Aviator and Astronaut that I believe translates well for mariners: “A superior pilot uses his superior judgment to avoid situations which require the use of his superior skill.”6

FIND (OR MAKE) A CHECKLIST

When weather planning, I suggest making a weather checklist; list out Departure – enroute – destination conditions and incorporate a planned alternate destination. The question to ask when making this checklist is: What if? Pilots plan for alternate landing fields. Why can’t sailors do the same?

Organize your onboard weather displays and monitoring equipment logically in an order that makes sense for the voyage, including contingency for failure.

If you incorporate paper charts – make a habit of plotting significant synoptic weather features on a transparency over the navigation chart (with non-permanent color markers); NOAA National Weather Service has an array of symbols to learn and use. Plot from synoptic charts, surface weather reports, forecasts, and vessel reports. Indicate the movement of these features if known. This provides a navigation tool and visual cue to avoid hazards reported and forecast conditions of significance.

As aviators file flight plans – be in the habit of filing a Sail plan – be it with an official agency or a responsible person. SAR needs the details of the voyage and who to contact if an unplanned non-routine event delays, impedes, or threatens the vessel and crew. Have your safety plan and emergency beacon equipment current and at the ready.

CONCLUSION

The Gulf Stream remains one of nature’s grand sailing freeways. Power boaters miss out on the beauty of this while under throttle. A tactical approach is necessary so that you don’t overshoot the Bahamas going one way, or come up short the other – having to fight your way back upstream like a Salmon. If you have ever observed an aircraft landing in a strong crosswind – skill and planning is required not to shoot past the runway centerline when turning onto final approach.

May fair-weather cumulus smile down upon you; and the spray on your jib be warm and friendly. If you’ve got some stories relating to your relationship with the Gulf Stream, leave them in the comments.

SOURCES AND ADDITIONAL READING

- National Transportation Safety Board – Marine Accident Brief – Sinking of Tall Ship Bounty. www.ntsb.gov MAB1403.PDF. 2. Multiple Florida state and National News broadcasts Jan. 06, 2024.

- Sir Robin Knox-Johnston: Sailing Legend | Documentary Clipper Round the World Race; YouTube May 14th, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WdIIYr1GdIs

- https://www.weather.gov/bmx/outreach_microbursts

- https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/remembering-frank-borman

- Sailing Alone around the world, Captain Joshua Slocum, ©1899.

- Admiral of the Ocean Sea – A life of Christopher Columbus, Samuel Eliot Morison ©1942.

- Heavy Weather Sailing 4th, Edition; K.Adlard Coles. Part 2 – 31 Page 332 Wind Waves – Sheldon Bacon. 10.

Late November 1977. Heading to Antigua from Cape May, NJ. Crossing the Gulf Stream, ran into 100 mph winds, 50′ seas. Knocked off the bow pulpit, cracked the boom, broke the skipper’s arm. Hove-to under storm jib for thirty hours. Ended up in Bermuda ….

Excellent article Rodger…being a pilot myself, the quote from the late Col. Frank Borman is priceless…Thank you.

I helped a friend return to CT on his 39 ft. Carter after the Newport – Bermuda race many years ago. He intended to sleep most of the way home and assigned me to be captain, as I also owned a 39 Carter. I brought another seasoned sailor as well as 2 other crew who wanted to get some experience. We knew we were going to hit a squall on the way. It ended up ~40 hours of 40 knot winds & 40 ft. seas. The owner awoke to help out, but the 2 new crew got seasick and I learned why the Race requires a 2nd forestay as the winds were on the port quarter and our bow plowed into every wave. The boat and all the crew survived.

My worst weather experience at sea was on Exuma Sound in the Bahamas. We were in a Selene 53 (85,000 pound trawler yacht) headed from the Exuma Cays to Emerald Bay Marina on the east coast of Great Exuma Island. It was mid-summer. We entered the Sound with winds 15 knots from the SSE (pretty typical for this time and place) and the sky thickly clouded but not dark (a bit cloudier than usual for this time and place, where typical weather is isolated cumulonimbus “cells” bringing heavy, but brief & local, thundershowers). We had a blue water run of about 30 NM from the southernmost deep-water cut off the Bahama Bank, to Emerald Bay, in a well-enclosed basin. When we were about half way along the leg, the wind suddenly rose to 30 knots and then to 55 knots (according to the boat’s Airmar ultrasonic anemometer) and seas rose to a very steep 12 feet. All we could do was to throttle back, barely maintaining steerage-way, & to steer into the seas until the wind dropped. A lot of green water came over the bow and sluiced down the side decks. After about half an hour, the wind dropped, & the seas soon fell to a level (8 feet it seemed) where we could resume our coarse toward Emerald Bay. I believe two things saved us from a much worse experience: First, the boat had Naiad hydraulic fin stabilizers, and they significantly reduced the vessel’s roll, especially upon resuming our course toward Emerald Bay, which put the seas on our port bow. Second, at the beginning of every season when the boat was in the yard, we had a fuel polishing service drain all the fuel from both our tanks, polish it, and returned it, and we then filled the tanks in the yard from a tank truck with good filtration; thus, no there was no sludge in the tanks to get stirred and choke off fuel to the engine. If the engine had died, we could well have foundered. I should add that the Selene 53 turned out to be a pretty good boat in an extreme head sea.

I’ve had the good fortune to sail safely to and from the VIs to Bermuda to Newport 6 times in the last four years. It all comes down to planning your route and checking weather well ahead of the trip and throughout the voyage. When in doubt at all then stay in port until it is reasonable to go. That said the weather can change quickly especially up the East Coast of the USA. So, prepare for the worst scenario and hope for the best. Safe passages to all!