Leave water from any source in a storage tank for a while, and interesting things will start to grow. Only the purest water in an airtight bottle will have a long shelf life. But not all bottled water is what the label says it is. For a cruiser, there are two water-testing tools that are important, and a third tool that is helpful in determining what is going into a tank and managing the quality of fresh water on a long-range cruising boat.

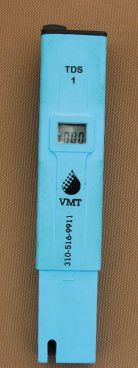

The first is a TDS (total dissolved solids) meter. Reverse-osmosis (RO) water systems can go bad so gradually that the users tastebuds do not recognize that theyre drinking water that has become more brackish than fresh. This could become a health issue. RO water should have a TDS of less than 500 parts per million (ppm). RO output water should be constantly monitored for TDS.

There is another important use for a TDS meter. A cruiser in the Philippines tested his distilled battery water, bought at a local hardware store. The TDS was an extremely high 950 ppm. This was the same as the heavily calcified well water coming from the marina faucet. The TDS for battery water should be no more than 5 ppm. In the same location, the clear bottles of locally distilled drinking water had a TDS of 2 ppm. Nevertheless, each bottle of drinking water was tested before adding to the batteries. There are times when rain water is surprisingly dirty and not suitable as battery water. A TDS meter will help identify the quality of rainwater.

Swimming Pool Test Kit

Without a TDS meter and microbe test kit, there is no way of knowing what is being washed from the clouds, living in the pipes of a city water system, or in clear tropical waterfalls. To ensure safe drinking water and to keep water tanks free of muck, it is cheap insurance to add chlorine to the water. The World Health Organization advises adding about 1/8 cup of 5.25-percent sodium hypochlorite (a form of common chlorine) to each 50 gallons of water for sanitizing. There are variables, like the pH, TDS, and how many microbes are in the water, which determine exactly how much chlorine bleach to add to drinking water. To confirm the chlorine content is sufficient but not too much, you can use aquarium test strips or a swimming pool test kit. The goal of a first dose is to get the chlorine level to about 1, if not a little higher. This can require a bit more than 1/8 cup in 50 gallons. This will be enough to kill most pathogens, bacteria, and mildew. Chlorine gasses off quickly, and in a few days, as the chlorine loses its effect, any taste or odor will disappear leaving the water clean. (A carbon filter at the tap will also help eliminate the chlorine taste.)

Any harm that chlorine in purification amounts would cause a 316 stainless-steel water tank would be negligible. However, over time, it can pit the inside of an aluminum tank. You can paint aluminum tanks with two coats of a non-toxic, food-grade epoxy paint that doesn’t contain solvents. (See Painting a Water Tank, PS December 2014 online, and Preventing and Treating the Tainted Tank, PS July 2015, for ways to sanitize an aluminum tank and more details on sanitizing with chlorine according to World Health Organization standards.)

A third optional test tool is the PathoScreen made by Hach Co. (www.hach.com). This determines the presence or absence of hydrogen sulfide-producing bacteria, which include pathogens. To use it, pour your water sample into a sterilized test tube, then open the kits small silver packet and empty the gold-colored powder into the test tube. Screw on the black lid, and shake the test tube until the contents are dissolved. The powder encourages microbe growth. In 24 hours, if the water turns black, there are microbes and possible pathogens. But this test does not tell the quantity or what specific microbes are in the water.

Just because a city facility supplies water to a faucet, or island natives drink from a stream, or rainwater looks clear, does not mean it is safe to consume.