Man overboard gear standards are behind the times because the sample size is tiny and the facts surrounding an accident are often clouded and disguised by difficult circumstances. But fixing this is pretty simple; piggyback on standards that have been developed for climbing and industry. The following are just some of the steps that a sailor can take to improve his chances of staying on board.

Safety Tether Design Basis

The crew retention rigging must be designed to function. In industry there are requirements that systems are designed by a competent individual. On boats, even at the highest level, this task is left up to sailors with little or no training.

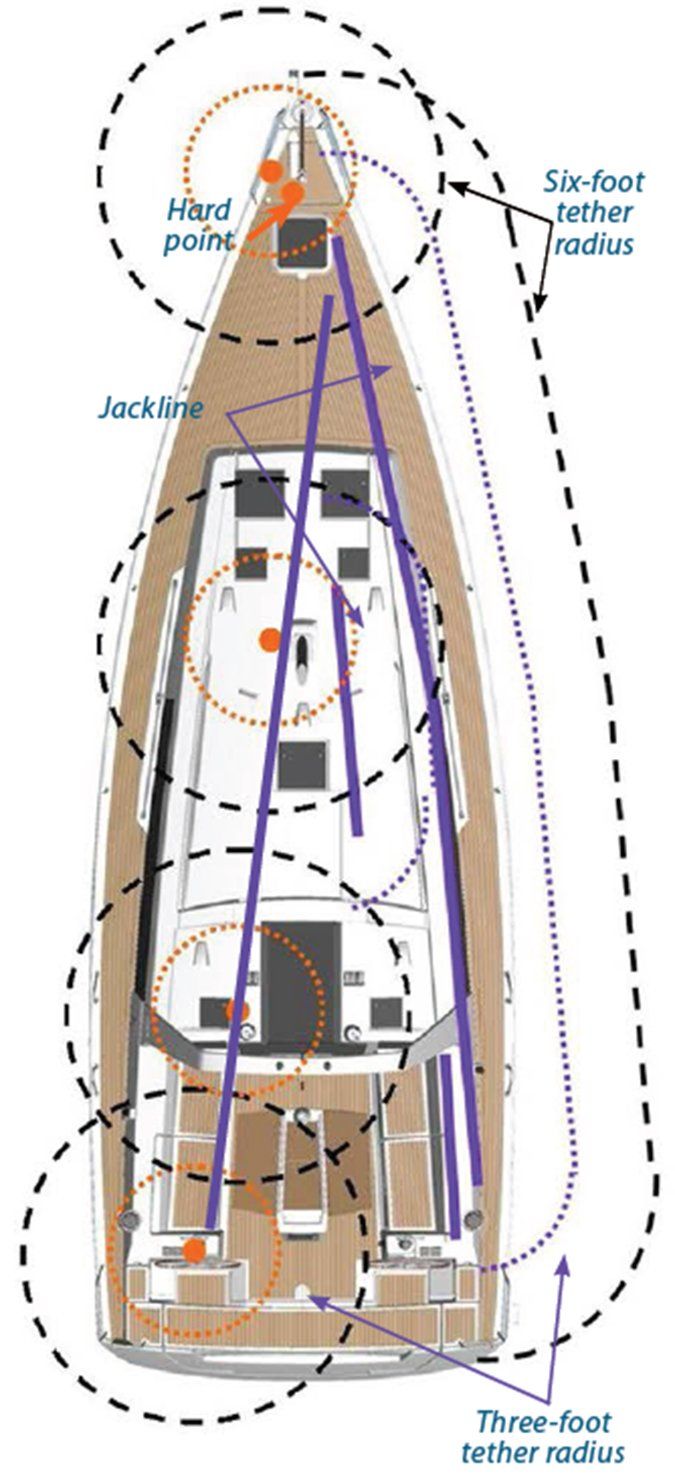

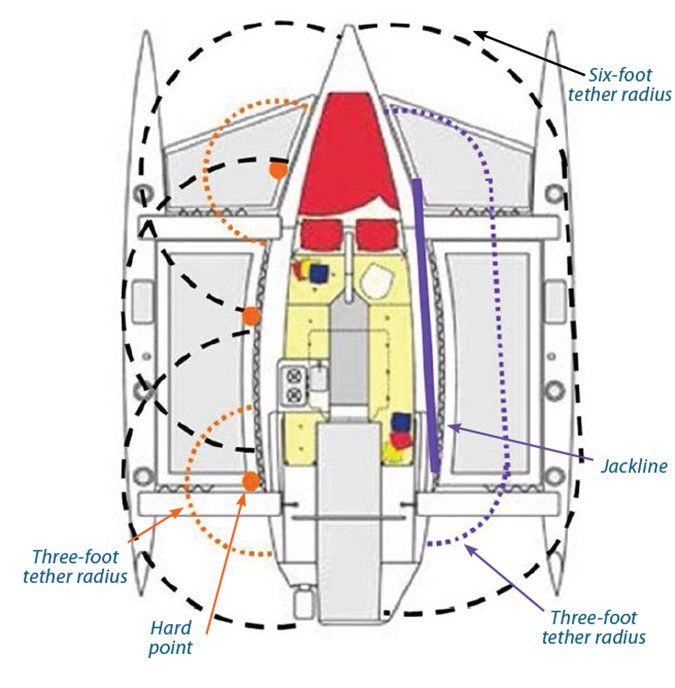

Jacklines, work station tethers, and hardpoints should be where they are needed; for example, we run the jacklines cleat-to-cleat because it is easy, not because it is right. Designers should include jacklines part of the basic design, right up there with running control lines, unburdened by the positions of existing hardware. Such designs would take into account acceptable stretch and load factors, specifying the number of sailors that could safely clip in.

For retrofits, one possible approach is to develop design tables for jackline materials based on a set load at the mid-point, which would keep stretch reasonable and stresses within acceptable safety factors. Experts in popular racing boats could develop deck layouts that would address things like hard point and jackline location, and likely fall trajectories.

Training

Sailors need to approach fall protection as climbers do. The cross-loading incident suspected of contributing to the death of Simon Speirs during the Clipper Ventures race last year (see Safety Tethers Under Scrutiny, PS March 2018) wouldnt surprise a climber.

Watching out for cross-loading and impingement at the clips opening gate is instinctive for them. Climbers we spoke with easily identified that Speirs had too much slack, that the clip was flimsy, and pointed out that combining a non-stretch tether with a chest harness was just asking for soft tissue injuries and perhaps broken ribs.

Through experience and training, climbers have cultivated the habit of looking at any hazardous position in three dimensions, including all probable fall trajectories and outcomes.

One step toward safer practices would be a curriculum broken down by boat type and sailing type and written experts in each discipline. The curriculum would cover both general and type-specific practices.

Were certainly not qualified to write the whole curriculum. Its a huge undertaking and will require the involvement of many experts in both sailing and engineering. But lets get started.

General Advice

Plan before going forward. Have in your mind what needs to be done, in what sequence, how you will do it safely, and what you will do if that does not work. This is particularly important for single-handers. Never leave the cockpit assuming you will wing it.

Think of the edge of the deck as a 500-foot cliff. As soon as you fall over the railing, the odds of a good outcome plummet. Move and use MOB retention systems as though the edge of the deck were a cliff. Remember that innocent looking water can kill you in a few minutes.

Be familiar with tether requirements. These must meet ISO 12401 and World Sailing standards. There must be two legs and the harness end should be releasable.

When to Clip-In

When attacking a vertical face, climbers are on belay throughout the climb. But on peak ascents, or multi-stage climbs long portions of the climb are carried out free of any safety tethers.

Can we expect cruising sailors to be clipped in to the jackline all the time when sailing? Probably not, but, the following conditions should almost certainly require clipping in.

- After dark.

- Cold water. The wearing of wet suits or dry suits can modify this.

- Solo in open water.

- Rough conditions. Obviously this varies with both the boat and the experience of the crew.

- Off-shore. This includes all open water where the boat is not closely observed by chase boats.

- Difficult to recover. This includes sailing with inexperienced crew, short-handed crew, spinnaker up, rough conditions, night, and any other condition that makes recovering an MOB difficult.

When Not to Clip In

There are times when it may be better not to clip in-or the standard clip-in procedure should be modified. Any fall over the rail on a tether is likely to cause serious injury, up to an including drowning in the bow wave.

- Closely supervised in-shore racing.

- Capsize-prone boats (dinghies).

- Very fast boats. Hitting the water while tethered at high speed can result in fatal injuries. On such boats tethers must be designed to positively retain sailors on-board while at a workstation.

Quick-Release Snap Hooks

There may be times when a release-under-load tether snap-hook may not be desirable. Many offshore racers don’t use spinnaker shackles and climbers avoid them because they can open accidentally. Some of these are situations where recovery is very unlikely:

- Solo on open water.

- Inexperienced crew that may not be able to recover an MOB.

- Extreme conditions.

- Very cold water without a dry suit.

Gear Inspection

You are going to rely on this equipment, perhaps even leaning on it for security. It has to be right.

- Watch for sun damage. Nylon webbing products is weakened about 50 percent by ultraviolet after one-year of continuous sun exposure. Polyester webbing and Dyneema are more durable, losing 10-25 percent per year. Jacklines and tethers should be marked with a date and retired based on estimated days of use.

- Check tethers. Carabiners can get sticky with dirt, dried salt, and corrosion. Webbing can cut on sharp edges. Inspect before every use. Formally inspect several times each season.

- Check jacklines. Inspect for wear and proper rigging.

Work Stations

Install work station tethers where needed. Specifically, inspect the anchor point for chafe. Because these are typically left in place, they should be replaced after one-year for nylon and three years for Dyneema.

Harnesses

Most harnesses are imperfect and require some modification. One of our most useful modifications is custom ascender-style leg loops instead of a crotch strap.

Chest harnesses are for positioning only, not fall protection. Serious injury can occur if you fall overboard wearing a chest harness. These types of harnesses have been banned in both climbing and industry for this reason. This is not something the manufacturers want to hear, but sailors need to understand it and memorize it up-front.

Crotch straps provide some support, but they have plastic buckles and are not load rated for falls. The UIAA international governing body for climbing make this quite clear in the published standards for harnesses: NOTE 1. This type of harness alone cannot support a person in the hanging position without permanent injury in less than one minute.

Chest bands must be mid-sternum and never below the sternum (ISO 12401). If the chest band is on the lower ribs it can cause suffocation or broken ribs. Too high and it will damage nerves in the armpits, be very painful, and strike you dangerously in the face.

Double-check that the snap-shackle is fully closed and that the release lanyard is hanging free. It can have balls or knots for grip, but it should not have a finger loop, which can snag easily. The corollary of release-under-load is that it can release when you don’t want it to.

Chest band should be snug when the chest is fully expanded. Even so, it is always possible to slide out if you lift your arms and exhale, particularly in foul weather gear.

Wear leg loops if possible. Without them, there is a good probability you will slide out if you lift your arms to help, particularly with wet foul weather gear.

Impact-rated leg loops are a significant safety improvement over a crotch strap, keeping the harness from riding up without pinching the crotch area.

If you are being hoisted by the harness, do not help by lifting your arms. Keep at least one arm down; it will hurt but you this will help you from slipping out of the harness as you are lifted..

Jacklines

In our view, jacklines don’t get the careful scrutiny the deserve. Here are some things to keep in mind as you design a jackline system for your boat.

- Keep slack out of the system whenever possible.

- A jackline is subject to tightrope stress, generally 4-8 times more than the fall impact force, and must be designed for this.

- Long jacklines stretch. High modulus materials can limit this, but the stress goes up so they must be 1.5-3 times stronger than World Sailing minimums. Some slack is required in cable and high modulus jacklines; this must be part of design basis.

- Nylon jacklines must be less than six feet. They will stretch too much. However, nylon can be superior to other materials for jacklines less than six feet because it provides impact absorption.

- Polyester jacklines must be tight.

- Dyneema jacklines shouldn’t be lashed tight; you need some slack to prevent excessive tight-rope effect tension.

- Intermediate loops spliced into Dyneema jacklines can serve as hardpoints, preventing the sailor from being washed the length of the jackline. However, since this may result in more sailors using the same jackline (the World Sailing design basis assumes a maximum of two sailors per jackline), the strength requirement will increase.

Moving on Deck

More often than not, the person who goes overboard was distracted by work. At the time Jon Santarelli went overboard and drowned during this years Chicago Mackinac race, he was reportedly moving aft to tend to a line.

Use two hands, brace your feet when practical, and watch for waves.

Get low. Crouch forward of the mast. On smaller boats, crawling and scooting is appropriate in rough conditions. In this way, the lifelines stay above your center of gravity.

Wear gloves. You need to be able to hold tightly to jacklines, wire rigging, and lifelines, without fear of injury.

Centerline jacklines make sense off the wind and in moderate weather. When heeling driving up wind, a windward jackline keeps you farther from the lee rail, which is the only place you are likely to slide. Yes, it is narrow beside the cabin, so use a short tether and get low when you need to.

Clip on anytime you will be focused on something other than movement and holding on.

The tethers should be to windward and have very little slack. Near the bow, particularly on multihulls and fast boats, one tether should prevent flying forward should the boat stuff a wave.

Keep the tether short especially on fast multihulls when you can’t afford to be thrown off station. Long tethers that allowed the wearer to drag in the water have been linked to several sailing fatalities. A short tether will usually keep you on-board. When it does not, the impact force from the fall will be less. In the incidents we researched, if the sailor was overboard with a short tether he was either able to reboard on his own or the crew was able to quickly haul him aboard without major injury.

Use hardpoints and work-station tethers.

Clip short of bow and stern. You can reach anything you need with a 2-meter tether while clipped 4 feet back, so there is no reason for jacklines to extend from bow to stern. Likewise, hardpoints should be slightly short of the bow and stern depending on the height of the anchor point. Tether can be doubled around some hardpoints (mast, pulpit, etc.). Doubling the tether around the jackline may increase chafe.

Other Precautions

Many overboard tragedies occur when a boat is at anchor, when the crew is not clipped in, or particularly wary of any danger. Here are other steps that weve taken to provide an added safety.

Temporary or permanent chest-high lifelines rigged to shrouds can be a great addition for cruisers.

Add non-skid anywhere your foot can go. Areas around hatches and cleats are too often left slick.

Add non-skid on steep slopes. Often sloping cabin sides become walking surfaces when heeled. And even if a surface is too steep to walk on, when a foot is placed there in a stumble, good non-skid will make the slide considerably slower so that you have time to recover balance.

A swimmer-accessible ladder is a must for cruisers and short-handed racers. There have been serious incidents, even at anchor, when a sailor fell in and was unable to reboard. A ladder can be a great aid to recovering an uninjured MOB. However, it may not be usable in rough weather and do not assume the victim will be able to get to it.

Keep lines out of the water. A common reason for not being able to start the engine during MOB recovery is the risk of fouling the prop with lines in the water. Keep the tails tidied up at all times so that this is not a risk. If you need the engine, spend just a few minutes hauling the lines in. Shorthanded or with less skilled crew, using the engine may be the safest way.

Charlevoix Police Department

Recovery

You should develop a means of recovering crew overboard that does not require leaning over the rail, but if the victim is unconscious or disabled there are few options. Stern platforms are a big help here.

If the victim is still tethered, that makes things a little easier, but you may still need to rig a lift to bring the crew back on board. Halyard loops near the jackline end of the tether allow a halyard or other recovery line to be attached to the victim. Once the victim is connected with the lifting line, the tether can be released from the boat.

In some cases, you might have to quickly move a tethered victim aft out of the bow wave to a more convenient lifting location to prevent drowning. And eventually bringing the victim aboard near the lifeline lifting gate. Practice this. For more details on man overboard recovery, see “Man-Overboard Retrieval Techniques“, or our ebook, Man Overboard Prevention and Recovery, available at the online bookstore.

Safety Tether Nitty Gritty

When events conspire against us, we don’t want to become unwitting accomplices. The basics of using harnesses and tethers might seem simple, but overlooking certain details in their fit and use can render this equipment useless, and possibly harmful.

Clipping in for Good

Where and how you clip-in is as important as what type of clip you have.

- Avoid side loads and gate impingement. Consider all likely rotations.

- Clip into toerails from underneath (gate up).

- Clip into horizontal U-bolts from underneath (gate up).

- Don’t clip back to the tether webbing.

- Learn the hardpoints ahead of time (position, strength, best clipping method, and side loads).

- Don’t park the unused tether leg on your harness. This disables the release-under-load feature. There should be a parking loop such as the Wichard smart loop, or there may be room inside the harness-end tether.

- You can keep an elasticized two-meter secondary tether out of the way when not needed by wrapping it behind your back like a belt, comfortable while grinding but still handy.

- Practice clipping in fair weather. Clipping and unclipping from jacklines and hardpoints needs to be instinctive, even in the dark with gloves on. Observe how the carabiners move around when clipped into hard points and along the jackline and fix any snags or problem areas.

Practice working in fair weather. Learn how to walk the deck to avoid fouling the tether with all sail combinations. Learn the minimum tether length and best clipping point for each task. For example, when approaching the forestay or mast, you should know where the short tether goes and clip it before you begin working.

Never clip to lifelines; they are the wrong place, the stanchions bend and they do not offer firm support because of this.

Never use a pulpit or stern rail as a sole anchor point; they are useful for positioning but should be backed up with another clip on a jackline or hard point.

Never clip to standing or running rigging. The latter should be obvious; it can move suddenly. Standing rigging can be strong, but the screws and toggles are subject to damage and there are too many ways for a carabiner to cross load or load the gate from the inside.

A webbing or Dyneema sling extension added to a standing rigging U-bolt can be acceptable in these cases.

Conclusion

A parting thought, for experienced sailors that know how to stay safe. It seems the actual safety record of active experienced sailors and rock climbers does not continue to improve with age. Many of us reach a balance of risk that we are comfortable with, and unless we consciously adopt risk-free habits, we get hurt or dead in spite of knowing better.

We become complacent, comfortable that our knowledge will kick in when needed, and take habitual short cuts without consciously realizing it. If you’re comfortable with this, well OK.

Its a lot. The designer-yes, this is an engineering design problem-needs to consider the forces and directions involved, as well as consider where people need to move, which directions they will likely be thrown, and what fall directions are dangerous.

The sailor needs to put his engineer hat on and learn the limitations of the equipment. If a job cannot be done safely, we need to change the job or engineer restraint systems that make it safe. We need to graft this mindset-common to industrial work-at-height designers, rock climbers, and mountain guides-into our sailing practice and culture. Sail and work on deck with confidence, but treat that three-foot fall into the water as if it were a 500-foot cliff.