C&C stands for George Cuthbertson & George Cassian, the design team which in 1969 joined in partnership with Belleville Marine Yard, Hinterhoeller Ltd. and Bruckmann Manufacturing to form C&C Yachts. (We noted with interest that Bruckmann recently built a custom Niagara 42, previously built by Hinterhoeller.) The company had a tumultuous history, from growing to capture an estimated 20% of the US market during the 1970s, to suffering a devastating fire in 1994 while owned by Hong Kong businessmen Anthony Koo and Frank Chow of Wa Kwang Shipping. Along the way they built a tremendous number of boats, not only in the racer/cruiser genre that was their mtier, but also the Landfall cruiser line, and a few oddballs such as the 1977 Mega 30 with retractable fin keel. It and a handful of others simply bombed.

Most boats were built at one of several Ontario, Canada facilities, but short periods of construction also took place in Middletown, Rhode Island and Kiel, Germany.

In 1998, Fairport Marine, which had bought Tartan Marine, purchased the C&C name and some molds and moved the remnants to Ohio. Since then, Fairport has developed a few new designs, notably the C&C 110 (see PS, October 1, 1999) and 121. Other than the name and the emphasis on performance, however, there is no tangible connection between C&C today and the giant of 25 years ago which so dominated the North American yachting scene. Indeed, Red Jacket, designed by C&C and built by Erich Bruckmann, won the 1968 SORC, and the C&C Redline 41 Condor won it in 1972. Back then, production boats had a shot at major race events and a few companies, including Tartan Marine, actually had factory racing teams.

The Design

The C&C 27 followed quickly on the heels of the successful C&C 35. The design is attributed to 1970, with the first boats coming off the line in 1971. The boat evolved through three subsequent editions-the Mark II, III and IV (the latter are hulls #915-#975, according to an owner)-with the latter finishing in 1982. But the hull was essentially the same and not to be confused with the MORC-influenced 27-footer that followed about 1984, with an outboard rudder. That boat lasted until 1987.

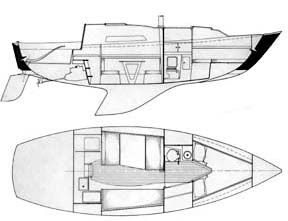

The C&C 27 is a good example of what made the company successful-contemporary good looks with sharp, crisp lines that still appeal today. The sheerline is handsome. Below the waterline, the swept back appendages are dated but thats of little consequence to most owners. In the Mark I version, the partially balanced spade rudder is angled aft, with a good portion of it protruding behind the transom. In one of his reviews for Sailing magazine, designer Robert described the C&C 27s rudder as a scimitar shape that was long in the chord and shallow. In 1974, the rudder was redesigned with a constant chord length and much greater depth and less sweep angle.

The keel, too, was redesigned in 1974 though both are swept aft like an inverted sharks fin. The new keel was given 2-1/2″ more depth and the maximum thickness moved forward to delay stalling. Hydrodynamic considerations aside, the worst that can be said of the 27s keel is that it takes extra care in blocking when the boat is hauled and set down on jack stands (or poppets as they are called here in Rhode Island). Without a flat run on the bottom of the keel, the boat wants to rock forward.

The rig is a masthead sloop with a P or mainsail luff length of 28′ 6″ and an E or foot length of 10′ 6″; interestingly, this gives an aspect ratio of .36, nearly identical to the .35 ratio of the Tartan 4100 reviewed last month. In response to the September article on skinny masts with single lower shrouds, the owner of a 1974 model wrote, My 1974 C&C 27 has double lowers with a tree trunk of a mast, which I know will support any headsail in any condition, probably even if I drove the boat full steam into an immovable object. Not so the earliest models, however; the photo on page 30 is of a C&C 27 with single lowers.

The owner of a 1977 model wrote to say that the Mark I and II models had shorter rigs and more ballast. The change occurred in 1974, along with several others, some of which weve already noted.

Length overall was first given as 27′ 4″; for later marks it is listed as 27′ 11″. Waterline length started at 22′ 2″, increasing to 22′ 11″. The bow overhang is attractive, but more than is found on most boats nowadays. Remember that waterline length directly affects speed.

Displacement, too, changed over the years, between 5,180 pounds,5,500 pounds and 5,800 pounds. (The owner of hull #54 says that boats before #250 were 1,000 pounds heavier.) Depending on which waterline dimension you use, the displacement/length ratio (D/L) ranges from 211 to 237. The sail/area displacement ratio (SA/D) is between 17.3 and 19.4. With moderate displacement and a generous sail plan, the C&C 27 is fleet. PHRF ratings for the Mark I average around 200 seconds per mile, dropping to about 190 for the Mark II and 175 for the Mark III.

Construction

C&C Yachts was a pioneer in balsa sandwich construction, but the early C&C 27s had solid glass hulls. Decks were balsa-cored. An old brochure says the marine ply bulkheads are taped and bonded to hull and deck, though photos show a headliner which seems to make deck tabbing not possible. The same brochure says fiberglass is hand laid up using alternate layers of mat and cloth; no mention is made of woven roving, which is commonly used to add thickness quickly.

During this period, C&C used a molded fiberglass pan that incorporated the cabin sole and berth foundations, but did not extend higher. Berth/settee backs, galley and head cabinetry are plywood and access to parts of the hull is generally good.

One owner said that the cabin sole needs floors (supporting timbers) underneath.

Ballast is an external lead casting through-bolted to reinforced hull sections.

One trick C&C used in lieu of floors was to lay in thick bands of fiberglass athwartship maybe 6″ wide. These started on one side of the hull, crossed the bilge and up the other side.

A C&C trademark was the L-shaped aluminum toerail with slots to which you can fasten snatch blocks. Of equal benefit was the ability to use carriage bolts for the hull-deck joint, which could be installed by one person rather than two. Other builders quickly copied this feature.

A C&C web site (www.cnc-owners.com) accurately notes that C&C engineering, combined with the boatbuilding skills of Bruckmann and George Hinterhoeller, proved to the consumer that a fibreglass boat didnt have to be built like a brick outhouse to be good-light and rigid was perfectly fine.

True enough, though many C&Cs have their weak spots, which include bulkheads not tabbed to the deck (which may result in the deck lifting as the boat and rig work), thin laminates in the outboard edges of the side decks where stanchion bases are bolted, absence of backing plates on pulpits, and thin portlight lenses that should be replaced or fitted with storm shutters before venturing offshore.

For several years, the Practical Sailor test boat was a 1975 C&C 33, which was of the same vintage and construction as the C&C 27. When the decision was made to replace the crazed acrylic windows, we were dismayed to discover that they were a scan’t 1/8″ thick. New ones were cut from smoked Lexan. Fortunately, we were able to track down the gasket material from a company called Beclawat in Belleville, Ontario.

And, as with any older boat, prospective buyers should check for bulkhead rot where the chainplates attach (water runs down the plate and through the deck, which is difficult to seal), and for delamination of the decks, especially around hardware, whose bedding may have disappeared years ago. Rebedding deck fittings is a boring job, but a very important one because your balsa core is at risk. It helps to have a helper (one of you on deck, the other below). You don’t have to do everything the first year; start with the worst fittings and do them in groups, at least a few each year.

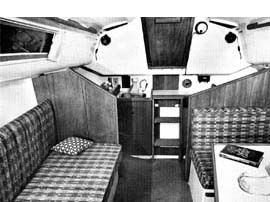

Interior

Twenty-seven feet is in many respects a magic number for a sailboat. At this length it is possible to have standing headroom without distorting the boats proportions beyond all good taste, and to have an inboard engine, with its obvious advantages and status. Headroom around the 27 is between 5′ 10″and 6′ 2″.

The accommodation plan is plain vanilla, tried and true: 6’+ V-berth forward, head and hanging locker, dinette with opposing settee, and aft galley. There are no quarter berths. In fact, its rather refreshing to review a boat without a queen size berth/aft cabin slipped under the cockpit footwell that has so little headroom you know that what goes bump in the night is going to be your forehead. Without berths back there, cockpit seat lockers provide valuable and generous stowage for lines, fenders, barbecue, cleaning supplies and all the other stuff that goes with sailing.

There is a bridge deck, which we think is a sensible choice as it a) helps keep water out of the cabin in the event the yacht is pooped, b) provides additional seating in the cockpit, and c) provides additional space in the galley which otherwise would not exist. Its drawback, of course, is the necessity to climb on and over it every time you go below.

A lot of C&Cs were not particularly well ventilated and the 27 is no exception. The big windows in the main cabin are fixed. Most air will enter from the forward hatch, which on a small boat in northern latitudes may be adequate, but hardly ideal for southern sailing. A Dorade vent over the head was available.

Performance

The C& C 27 was one of the companys most popular designs, numbering something like 975 or 980, and much of this was due to its smart handling and good turn of speed. Not surprisingly, owners generally rate its upwind and off-the-wind performance as above average.

Several owners said light air is the Mark Is Achilles heel and that a large genoa of more than 150% is necessary to stay competitive. In 1974 the rig was lengthened 3 feet and sail area increased from 348 sq. ft. to 372 sq. ft.

The boat handles easily. Turns 360 within its own length, said the owner of a 1973 model.

Extremely well balanced, wrote another owner.

The only negative comment made by owners concerns increasing weather helm as the wind builds. Reef early, wrote a number of owners. The owner of a 1971 model explained, The Mark III has a high aspect rudder; the original rudder gives the boat extremely bad weather helm.

Points very high, wrote the owner of hull #146. Shes easily controlled off the wind. If sail is reduced intelligently, shes a dream to drive. Rock solid at about 18.

On early models the mainsheet ran from the end of the boom to aft in the cockpit. In 1974 this was changed to a traveler on the bridge deck.

The early boats were delivered with Atomic 4 gasoline engines. Most owners said their boats back up beautifully. Best backing boat Ive seen, said the owner of a 1977 model. At the end of the production run, the engine was a small Yanmar diesel.

Comments on accessibility of the engine are mixed, ranging from easy to ridiculous, which may say more about the size of the respondents than anything else.

Conclusion

With prices in the low to middle teens, the C&C 27 represents a fair value-standing headroom for most, berths for four (owners say the dinette is a bit narrow for a double when converted), and inboard engine. The single-cylinder Yanmar of the late models is to be preferred over the old Atomic 4, despite being on the small side.

As mentioned earlier, we would pay particular attention to pulpit and stanchion bases and surrounding fiberglass for signs of cracks, the deck core, and to the interior support structure that handles mast compression for signs of rot.

Boats built after 1974 (Mark III) seem to sail better with the refinements incorporated-new rudder, deeper keel, taller rig, etc.

Of the many comments we heard about the boat, one in particular rings loudly: Simple systems, easy to maintain. Which means you wont spend an arm and a leg trying to keep the C&C 27 afloat, and that has a great deal of appeal for us.