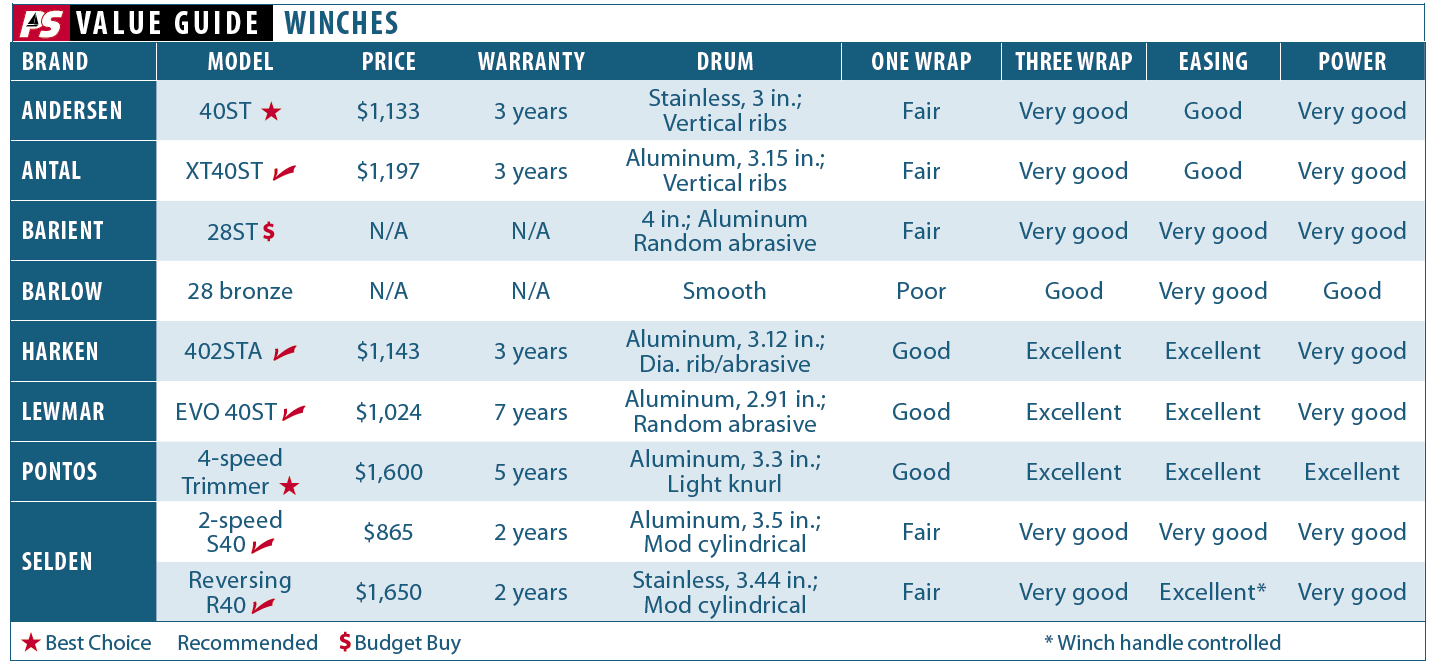

In our second look at sailboat winches, we put the deck hardware into action, sea trialing traditional winches that have stood the test of time as well as the newest trends in winch design. Our goal was to hone in on the operational aspects of each winch, scrutinizing how each drum handled line loads and noting which drum shapes were less prone to overrides. Testers also compared the effectiveness of self-tailing systems and the various drum surface finishes used to keep the line from slipping.

In order to expand on observations made during our winch bench testing, which was reported on in Part 1 of this series (The Ubiquitous Winch, PS August 2016 online), testers tracked down a number of cruising boats and racers equipped with the hardware we were evaluating. After sailing aboard a variety of sailboats, testers weighed the winches performance results and their observations to further define what each winch had to offer.

What We Tested

To keep within the parameters of the initial review, we narrowed our focus to winch options appropriate for 30- to 45-foot sailboats and went sailing on boats that fit within this size range. This led us to the major manufacturers of deck hardware: Andersen, Harken, Lewmar, Selden, and Antal. We also evaluated winches from Pontos, a newcomer to PS testing; details on this company and its products can be found in the August 2016 winch review.

Although a surprising number of midsized cruisers are turning to pushbutton winches, for now, our attention is aimed at manual winches. We must point out, however, that Andersen, Harken, Lewmar, and Antal offer manual winches that can be converted to power.

Sea-trialing refurbished, old winch favorites gave us a benchmark for measuring new product innovations. We bench tested, disassembled, inspected, measured, weighed, and micro-photographed both the new designs and the old standbys. Testers noted many valuable advancements and ergonomic upgrades in the new winches, but one trend-an increased number of plastic parts-raised questions about longevity.

How We Tested

During the sea trials, we evaluated how easy it was to wrap a sheet around the drum, ease it under load, and strip it off in a tack. We looked closely at self-tailers versus an open drum top and why most serious racing sailors still favor the non-self-tailing winch when it comes to sheet and guy handling.

In Part 1 of this series, gear ratio grabbed our attention, and the Pontos four-speed Grinder and Trimmer models were bench-test standouts. We made a special trip to Maine to test sail these innovative winches aboard Bernie Blums 39-foot InBox, a unique Bob Perry design that Blum has set up for single-handed cruising and club racing.

In addition to sea-trialing these new winches, we surveyed three professional sailmakers who commented on what winch attributes they look for aboard the wide range of boats that they sail. Those interviews appear with the online version of this article at www.practical-sailor.com.

During our initial inspections, testers noted the advantages of a slight taper on the drum shape. This helps coax line downward on the drum to alleviate overrides.

As for drum surfaces, typically, the operator can control friction on any winch. One wrap is for fast hauling, and three wraps are for winching, but this is just a starting point. Heavy loads on a narrow-radius drum may require more wraps than the same load on a large-radius drum. Also wrapping and unwrapping to control loads can be counter-productive.

Friction from a ribbed drum, popularized by Andersen winches, is a great friend when trimming. Others use knurled or abrasive drums. Too much grip can be a problem, however, when a slight, smooth ease is desired. Likewise, having to take turns off the drum in order to simply ease a sheet is counter-productive. The fact that Harken and other makers are adopting ribbed drum surface made us eager to compare drum designs.

The older winches that are still in service today gave us an important longevity baseline. Establishing which products have survived the test of time-and which design factors and material selection have enabled their longevity-set the stage for a comparative analysis. Our intent was to compare and contrast the new winches designs and materials with what has worked in the past, concluding with a look at operational efficiency as well as the potential for durability.

Old-school Survivors

Barient is still probably one of the most familiar names in marine winches, even though production stopped more than a decade ago after the company was purchased by Lewmar. West Marine, among other retailers, still sells replacement parts for these winches, and with proper care, even the aluminum Barient winches can be kept in fine working order for years to come. (See Winch Servicing Basics, PS October 2016 online.) With a new winch costing several hundred dollars, repairing an old winch is often the most cost-effective option.

This past summer, PS Technical Editor Ralph Naranjo spent five days sailing the East Coast aboard a 28-year-old McCurdy and Rhodes 44 (ex-Navy 44) with its original set of Barient winches. The hardware had recently been stripped cleaned and inspected, and worn pawls had been replaced. The maintenance process for these winches is relatively easy since the winch components can be removed, leaving the base in place. One of the reasons that these stainless-steel winches on the former Navy boats have held up is that the boats design spec called for oversized hardware. This meant that the winches had an extra safety margin to cope with the shock loads of a knockdown and could handle the cranking power of an uber-fit midshipman. Regular maintenance also ensured longevity. In our opinion, old Barients (or the Australian-made look-alikes from Barlow) can continue to offer good service if maintained and properly oversized for the job; they are Budget Buy picks.

Modern Winches

Initially, we were a little concerned about catalog and advertising blurbs that began with terms like styling upgrades, a modern look and lighter than ever. In other industries, these are code words for lesser quality and planned obsolescence, so throughout our testing, we were on the lookout for shortcuts in quality.

The glass-reinforced plastic used in newer winches has proved durable in other applications, but for those whod prefer traditional, high-nickel-content stainless and bronze winches, that option remains. Harken, Lewmar, Andersen, and Antal still offer lineups of traditional, all metal or mostly metal winches. Prices for many of these classics can be higher, but depending on the brand, the gap is not as great as one might expect.

Lewmar

Lewmar designs and manufactures winches that fit a wide range of sailboat sizes, and despite a significant trend toward electric and hydraulic products (a topic for future investigation), it continues to offer a variety of manual winches, including its time-proven Ocean model lineup. Recently, however, its less expensive Evo self-tailing and open-top winches have been garnering favor from both racers and cruisers. Its quick, no tool disassembly expedites servicing, and a center stem supports the spindle, ratchet, and pawl gears, as well as a bearing pack that does its job.

We sailed a race boat and a cruiser with the Lewmar Evo self-tailers and compared them with the classic line of stainless-steel Ocean winches used on the Navy 44 MKII. The Lewmar feeder arm and self-tailing jaw on the new Evo were quite unobtrusive compared to those on the Ocean winches. Even purists who would typically eschew adding weight or complexity have set up their club and ocean racers with self-tailers.

The Evos have a textured drum surface that grips sheets and halyards effectively and also delivers a smooth, even easing capacity. The new Lewmar winch handle is easy to lock in place and to release, plus the hand grip with a rotating top knob allows the grinder to use two hands when the loads increase.

Bottom line: The new Evo winches are an attractive price-point alternative for the popular Ocean Series, particularly for casual cruisers and racers. That said, the Ocean Series winches have a proven durability that will appeal strongly to the offshore cruising sailor. Recommended.

Harken

Harkens latest lineup includes Radial and Performa models plus its Classic winch line, which features a tried-and-proven, all-metal design available in bronze, chrome bronze, and stainless steel. Harken has tried several drum shapes and surfaces, and for the Performa line, the maker settled on a surface that is sandblasted and a radially ribbed drum. This combination allows more holding power with fewer wraps but still allows smooth easing.

Under sail, we liked the function of the 402STAs one-piece line guide and peeler. Time will tell whether the composite bearings and other injection-molded parts will hold up as well as the metallurgy in its Classic models, but two things were clear: Both the Performa and Radial winches were ergonomically designed, and the drums did an effective job taming the lines.

Bottom line: Production boatbuilders have flocked to Harken hardware in recent years, and this growth in domestic sales has prompted more research and development-as well as a steady supply of spare parts. Recommended.

Andersen

Andersens 40ST is a carefully crafted, all-metal winch with an aluminum-bronze alloy base and internal support structure for its stainless steel, vertically ribbed drum. Bronze gears rotate on well-supported, stainless-steel axles, and ball and roller bearings are used to reduce friction. These winches have long been recognized for their structural quality and reliability and are favored among many long-distance cruisers.

Testers liked how the jib sheets behaved on the polished and ribbed stainless-steel drum. The ribs provide sufficient line-holding power to resist sheet tension while still allowing the line to vertically slide and stack evenly on the drum as the sail trimmed. When it came time to ease a sheet, the line conveniently slid off the drum without any tension spikes or line surges.

Bottom line: Well-made winches with worldwide cruiser appeal and easy parts availability, the Andersen 40ST is a Best Choice.

Antal

The Antal XT40 is a winch with an evolutionary, rather than revolutionary, history. Its base is a high-strength, machined part as opposed to an anodized aluminum casting found in other winches. Bronze gears and stainless-steel shafts, along with a chrome bronze or anodized aluminum drum, are galvanically isolated with washers.

The self-tailer auto adapts to a wide range of line diameters. It also has a feature that allows the line to slip if the self-tailer arm is overloaded. This keeps the self-tailing mechanism from being damaged and prevents lines from wedging in so hard that it prevents release.

Bottom line: The vertical knurling on the chrome drum provided ample friction and still allows smooth release. The positive ratcheting function easily locks into place. This model was recently updated with a different drum mechanism and renamed the XT series. Recommended.

Selden

Selden has two winch designs, and in our bench testing and on-the-water trials, they delivered just what the specs called for. The R40 is a reversing winch in which the handle stays set while sailing, and the helmsperson simply counter-rotates the winch handle; the smooth easing action affords a fine-tune trim control of the jib sheet. We set off with a fair share of skepticism about the benefit of a reversing winch, but after a few tacks, we found it a to be a logical pathway to better sail trim. Its a great feature for the daysailor or club racer who sails shorthanded.

The S40 is a lightweight, two-speed winch that makes one-person sheeting a breeze. With the line snugly gripped by the self-tailer and the winch handle in place, you can manually pull in the slack without any added friction. When the load is too much, start cranking. No more fiddling to fit the loaded line in the tailer and put the winch handle in place.

The base is a well-designed composite structure, and we plan to long-term test the winch to see how well the materials hold up in comparison to winches with metal base assemblies.

Bottom line: Seldens reputation for solid engineering and fabrication rings true in its winch offerings. Both the S40 and R40 are Recommended.

Pontos

At the heart of Pontos Trimmer and Grinder winches is a unique clutch-and-trigger mechanism that auto-downshifts and upshifts according to the rotary force applied by the winch handle. This auto-shifting action seamlessly bridges two, higher speed/lower power gear ratios with two lower speed/higher power gear ratios. In essence, Pontos four-speed winches provide a much wider gear-ratio range in a winch that looks like a conventional two-speed.

In field tests, the Trimmer delivered the goods, taking all of the drudgery out of sheeting the last few inches on a highly loaded genoa. The process is a bit like down-shifting on a 10-speed while trying to climb a steep hill. What had been a two-handed strain became an easy one-handed twist. Testers were particularly pleased with the Grinder version of the winch, which has a ratio range that proves a real value in fast tacking and in outside asymmetric spinnaker jibes.

Bottom line: The Trimmers four-speed transmission worked flawlessly, and the execution of an innovative design impressed testers during field trials. Another Best Choice pick.

Conclusion

Testers found something to recommend in each of the winches. It came down to preferences. Our focus on drum surface adaptations showed the new textures improved grip at little cost to lines. Testers liked the Harkens diagonal ribs when it came to one-wrap trimming. The Lewmar Evos abrasive drum gripped sheets like the brakes on a Porsche. Andersen and Antal excelled in rugged design, while Selden delivered innovative tools for shorthanded sailing.

Innovations that showed up in our bench testing delivered the goods during sea trials. Under sail, the Best Choice Pontos Trimmer proved to be the most innovative new design, especially for shorthanded cruisers or racers.

The auto-shifting, four-speed gear selection process was hands-free and dead easy. As soon as we got to about 25 pounds of input load, there was a noticeable click, signaling that the person cranking should reverse the direction to shift gears. Doing so yielded a lower gear ratio, and if that was not enough, you could revers cranking direction two more times to harness the lowest gear (highest power). The net effect is a low-low gear with a super hauling power ratio.

If the wind slackens and the cranking requirements become less demanding, theres another clicking sound and the low-range doublet auto-upshifts back into normal two-speed operation. Without a doubt, the innovation award goes to Pontos for designing a four-speed, auto-shifting manual winch, and building it with easy-to-service, modularized components.

The only question our testing leaves unresolved is the durability issue. Internally, the Pontos Trimmer is an elegant bit of engineering, but it is more complex than the average, two-speed winch, and it has are more plastic parts-though disassembly and parts replacement are easy to do. We wonder about the toll that temperature changes, grit, and chemical contamination can have on these winches a few decades down the road. However, the big advantages of the engineering offset these concerns, in our opinion.

Efficiency is a key attribute in a winch, although this difficult to assess at a glancethus, our many repeated tests on the water and in the lab.

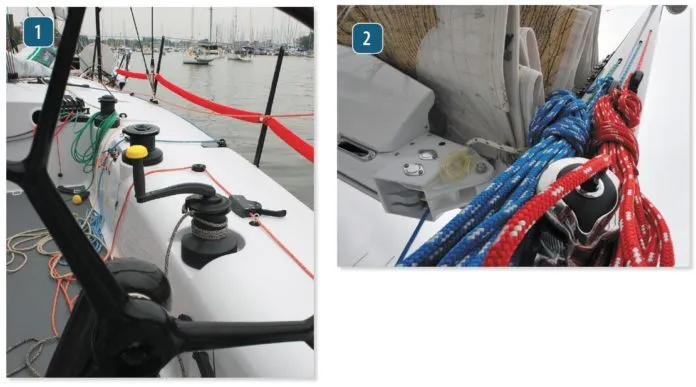

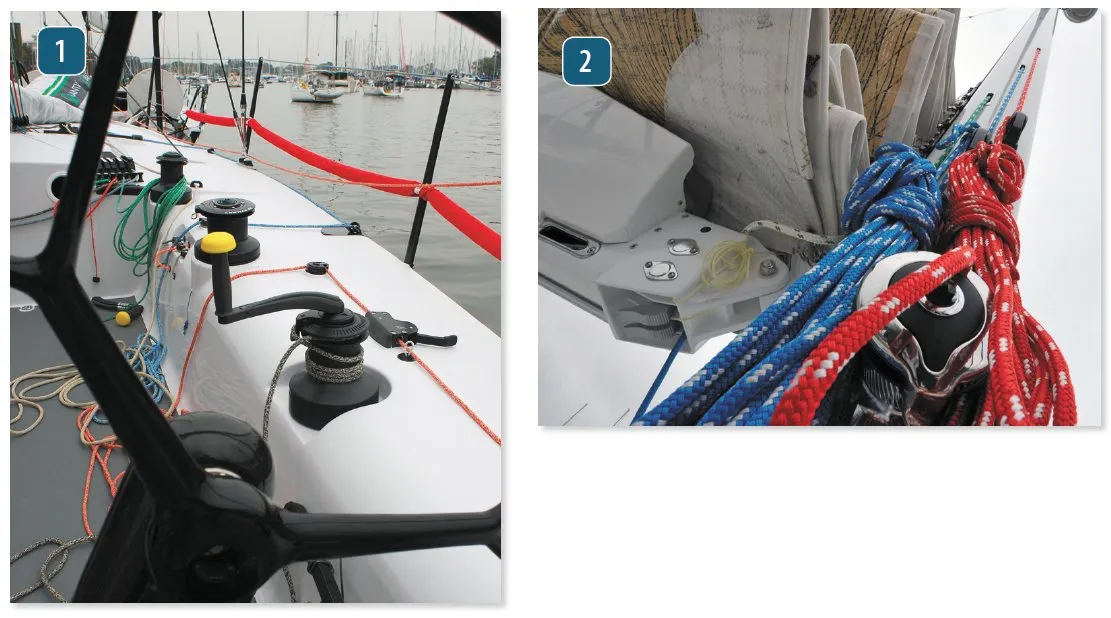

1.The Pontos Grinder and Trimmer differ in their four-speed ratios.

2. Selden’s reversible R40 switches into ease mode with the push of a winch-handle button.

3. Winch-drum radius is a key dimension when it comes to calculating a winch’s power ratio.

4. Selden uses a simple metric hex wench to release the S40’s top plate, enabling disassembly.

5. The angles iin Harken’s radially ribbed and textured drum are designed to prevent over-rides and facilitate a smooth release.

6. A ancient, two-speed Barlow 28 with an aftermarket selftailer assembly still does the job.