It doesn’t take a lot of brains to see that Catalina is doing something right that a lot of other sailboat makers aren’t. They’re the largest sailboat builder in the country, and a terrible year for them would be Valhalla for almost every other manufacturer. With more than 1,000 built in seven years, the Catalina 34 has to be in the running as the most successful production boat of the 1980s.

Equipment

When we went aboard the Catalina 34 at the 1990 Chicago Boat Show, we were first impressed by the equipment. Whereas many of the 1970s Catalinas came with what we considered second-rate hardware and gear that mandated owner upgrading, the 34, like the other contemporary Catalinas, is well equipped.

Self-tailing primary winches are standard and adequately sized; sail-handling hardware is all good; brand-names abound everywhere—stove, opening ports, pressure-water pump, head. It’s all the same or similar to what you’d find on 34′ boats costing $30,000 more.

The list of standard equipment is complete enough that you could conceivably sail the boat away with no options, a far cry from the old-fashioned method of selling a base boat with no lifelines, bilge pumps, or cushions aboard.

The 1990 boat we looked at carried a base price of $58,895, which included a main and 110% jib, mainsail cover, two-burner stove with oven, hot & cold pressure-water system, two batteries, 110-volt shore power system, boarding ladder, and lots of other equipment.

With electronics and other factory options (including a Hood furler and a microwave oven), the

boat had a price of $75,999, and the dealer was talking “special show price” to a serious customer on board. The only really essential pieces of equipment not on the boat were a couple of anchors, life jackets, flares, and a bell.

Design

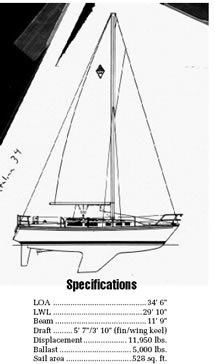

Except for the old Catalina 38 (which was not a Frank Butler design), all the Catalinas have a similar conservatively modern look—fin keel and spade rudder, short overhangs, and a flattish sheerline. The distinctive cabin house and diamond-shaped sail emblem help identify a Catalina.

The hull of the 34 is modern, with full sections to provide lots of room below. It seems more refined than the Catalina 27, 30, and 36, which is probably why we prefer the 34. Like the other Catalinas, the 34 combines a long waterline, a moderate to light displacement, and a large sail area to ensure good sailing performance.

The interior design is in the European mode, the first of the Catalinas to have the head aft by the companionway. Unlike European boats such as the Beneteau or Jeanneau in the same size range, however, the Catalina is very full forward, with a big Vberth cabin and a big dinette and settee ahead of the L-shaped galley and the nav station.

The aft cabin will be the principal cabin for most owners. It has a sizable athwartship berth. There’s a seating area between the berth and the galley, though we’re not sure how usable it would be.

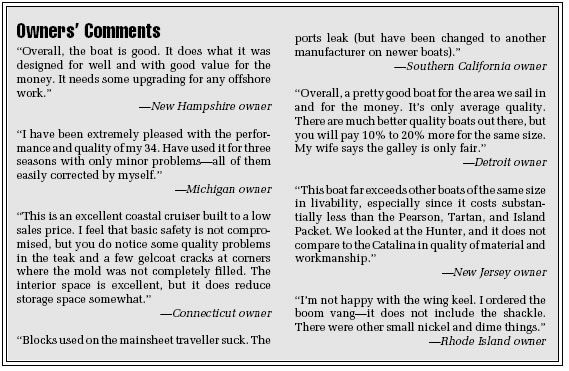

According to our owner survey, the interior is the most praised aspect of the 34, with comments like “most room for the money” appearing in a majority of reports. It’s always been a strong selling point with all the Catalinas—they’re hard to beat for sheer interior volume.

There are several aspects of the Catalina design we don’t like, such as the huge companionway hatches and molded furniture “pans” that limit stowage and access to the hull. But overall we cannot take serious objection to any important aspect of the design. They are wholesome but plain boats.

Performance Under Sail and Power

We sailed the 34 for only one afternoon, on Lake Michigan, and found the boat to be a good performer.

It was a puffy day, so the boat was occasionally overcanvased and developed a strong weather helm (due in part to a poorly shaped mainsail). Even with a good main, we suspect that cruisers will want to take an early reef as the wind builds; in fact, if we owned the boat we’d experiment with sailing it extensively under roller jib alone.

The 34 sailed well on all points of sail, but it seemed a bit sluggish off the wind without a downwind sail.

With a PHRF rating around 144, she is about in the middle of the speed range for contemporary boats her size, considerably slower than the J/35 but significantly faster than the Crealock 34.

We’d call her sailing ability respectable, good enough to make smart cruising passages and quick enough to sail to her handicap rating on the race course.

The 34 we sailed had the standard 5′ 7″ draft fin keel, but the boat also is available with a wing keel option, drawing 3′ 10″. Owner reports in our boat surveys give decidedly mixed reviews to the wing, some condemning it as only a “flopper-stopper” and not an efficient foil at all, and others praising its seaworthiness and the good ride it gives in waves. Unless we were desperate for the shallow draft, we’d be inclined to go with the standard fin rather than the wing.

Standard power is a three-cylinder Universal 25 diesel which we found adequate. However, owners again report mixed feelings about the engine. A few thought the boat was underpowered, a few said they wished they’d bought the three-bladed “cruising” prop, which is a popular option.

The boat does come with a four-cylinder Universal 35 diesel as an option, and this may be desirable for the cruiser as it gives more power.

To get better performance under power, we’d opt for the bigger diesel rather than the three-bladed solid prop, which would hurt sailing performance. In fact, we wouldn’t consider even a two-bladed fixed prop on this boat, since it would degrade one of the Catalina 34’s best qualities—her sailing performance.

Construction

Layup, laminates, balsa core and other construction details are conventional. The boat is generally well engineered and well-executed. It is certainly adequate for typical coastal cruising, weekending, and daysailing.

If good engineering means doing a good job of adapting means to ends, or materials to functions, then the Catalina 34 is well-engineered.

True, we don’t like the feel of the foredeck, which seems a little spongy compared to the teak-over-glass decks of our old Cheoy Lee. But we know a 1972 Catalina 27 well, and its foredeck has the same feel now that it had when new. It has served well and, we must conclude, was engineered and built as planned. We suspect the foredeck of the Catalina 34 will hold up for 20 years as well.

We don’t like the way the interior liner flexes either, or the way it hides most of the inside of the hull, but it holds up and it performs the cosmetic function for which it was intended.

The chainplates seem small when we compare them to the half-inch stainless plates on our Carter 36. But we’ve never heard of a Catalina’s chainplates failing, and they’re undoubtedly up to the job. Good engineering.

Some boats are overbuilt, which can be expensive— a waste of money for an American coastal sailor who has no plans to sail in the Southern Ocean. Worse is to build a boat no better than the Catalina 34 and charge $30,000 more.

Conclusion

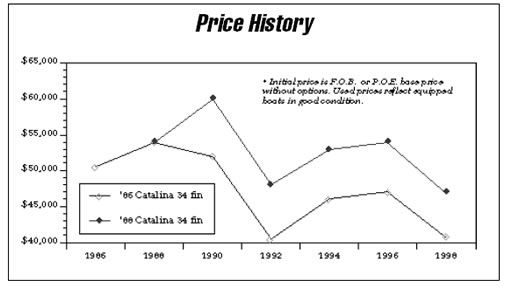

The Catalina 34 is a successful, all-around design from a hugely successful company. Because Catalina sells so many boats and runs an efficient manufacturing facility, its boats typically sell for less than other brands of comparable size.

This fact, plus the great number of used Catalinas on the market, mean that a buyer can be quite selective.

We do not recommend the Catalina 34 for extended offshore cruising, at least not without making some modifications to the companionway, upgrading the rigging, and possibly stiffening areas of the hull.

But the boat was neither designed, constructed, nor intended for such use. Indeed, most owners do not need such a boat. For the majority of American family sailors, the Catalina 34 will satisfy their needs just fine.