The BMW Oracle team recently repatriated the Americas Cup thanks in part to an absurdly high budget, a boatload of aerospace design and technology, and a very highly skilled crew. The win-along with a flood of e-mail from multihull fans-has given us good reason to revisit the multihull alternative. In this reader-requested sequel to our “Need For Speed” monohull report (September 2009), we focus on design features that make multihulls fast and fun to sail, and examine why many feel that two or three hulls are better than one.

Photos by Ralph Naranjo (unless noted)

To really get excited about performance in sailing cats and tris, lightweight, lean hulls, and sizable sail area are a must-for this reason, our review will focus more on the David rather than the Goliath side of the industry. The high-volume, heavier cruising cats have their own story to tell, but for now, well tack away from the beefy cruisers. Since exploring the art of speed under sail is the object of this exercise, well take this search to the corners of boat shows where the more thoroughbred performers tend to prowl.

Prior to western contact, Polynesians, Micronesians, and mariners of Indias Bay of Bengal demonstrated an acute knowledge of what makes a multihull work. For hundreds of years, the traditional cats and proas of Polynesian navigators crisscrossed the Pacific, forming the expansive cultural region known as the Polynesian triangle, bounded at the corners by Hawaii, Easter Island, and New Zealand.

In addition to large passagemaking craft, many Pacific and Indian Ocean islanders developed small coastal multihulls used for fishing and transportation. Among them were the fleet-footed “flying proas” that fascinated Magellan when he stopped in the Marianas.

Crude multihull “yachts” emerged in the 17th century, but it wasnt until the 1870s that nautical genius Nat Herreshoff introduced the first North American multihull yacht, Amaryllis. Foretelling a controversy that continues today, Amaryllis victorious debut in the New York Yacht Club Staten Island Race was immediately protested. She was stripped of her win, and multihulls were banned from competition for nearly 100 years. The same fate awaited the wide-beam sandbaggers (also known as “skimming dishes”) that were also outlawed because of their speed. For the next century, racing sailboats were left to dig holes in the water, tethered to hull speeds determined by waterline length.

Just after World War II, Rudy Choy and handful of Hawaiian surfers began working on high-speed beach cats, and in England, the Prout brothers were tinkering with multihull cruisers. However, it took surfboard builder Hobie Alter and the exuberance of the late 1960s to catapult the beach cat into the mainstream. To date, the company has made more than 100,000 14- and 16-footers.

A pilot named Arthur Piver kicked off an era of trimaran passagemaking, and designer/protgs such as Jim Brown, Norm Cross, Derek Kelsall, and Jay Kantola carried the baton, improving both performance under sail and structural reliability. Todays cruising multihulls emphasize comfortable accommodations, but designers like Jim Antrim, Gino Morrelli, Pete Melvin (of the design team Morrelli and Melvin), and others continue to place performance under sail at the very top of their vessel attribute list.

Design

As with monohulls, light weight directly correlates to higher speeds. Lighter displacement means theres less submerged hull, which in turn, decreases skin drag and diminishes the formation of waves that can rob speed. Give a light-displacement hull a long, lean, hull form, and its easy to see why many efficiency advocates proclaim the multihull to be their platform of choice.

Perhaps the biggest boost in potential speed comes from the ability to leave the lead ballast ashore and still deliver an impressive primary resistance to capsize. In the multihull approach to staying upright, form stability reigns supreme. According to this thesis, a boats massive initial stability, derived from spreading the hulls apart, obviates the need for a secondary righting moment (ballast).

The idea has merit, but so does the “never-say-never” rule. When it comes to ocean voyaging, steep wave faces and their destabilizing effect on form stability is also an important consideration. Keep in mind that multihulls are just as stable upside down as they are right side up, and many lose the ability to stay right side up at 60 degrees or so of heel. By comparison, the average monohulls limit of positive stability (LPS) is about 110 degrees or higher.

The debate rages. Monohull advocates believe that recovery from a spreader-soaking knockdown turns lead into gold. Multihull advocates point out that whether upside down and flooded or right side up, multihulls are designed to float.

In this review, we unapologetically sidestep the great argument over seakeeping ability of offshore boats, and instead focus on the excitement of modern beach cats and coastal cruisers.

It is interesting to note that in many of these smaller boats, a “hybrid” stability system is common, as movable crew ballast is added to the equation. Larger trimarans also present some unique stability variations all their own. These triple-hulled sailboats are influenced by ama buoyancy and lift. When the heeling moment generated by the sails increases, the leeward ama will either submerge or the hull and windward ama will try to fly.

Experienced multihull sailors recognize these important stability signals, and keep the boat flat on its feet by bleeding off sailplan pressure. Such indicators tell when the heeling moment is getting ready to overwhelm the righting moment of the boat. The art of flying a hull-or, as one might say, navigating on the brink of capsize-is part of the fun of Hobie sailing and was a crucial tactic in winning the 2010 Americas Cup. However, it is the last thing the owner of a Lagoon, Fontaine Pajot, Gemini, or other cruising catamaran wants to dabble in.

Huge initial stability allows a multihull to pile on sail. But designers have a real challenge in determining just how much sail area to offer in their consumer market boats. The more square footage that is available, the more exciting the ride. More sail area also means better performance in lighter airs. Of course, this extra horsepower also means that a reef will need to be tucked in sooner, and the traveler will need to be closely tended by vigilant crew.

It all boils down to one of naval architectures most fundamental theorems: An increase in beam leads to a cubed increase in stability. So by spreading the hulls farther apart, righting moment and sail-carrying ability increase noticeably. Unfortunately, theres a point at which too much beam becomes undesirable. A multihull designed with a really low beam-to-length ratio will resist capsize, but have a tendency to bury the bow and an increased potential to pitchpole.

To offer a broad look at the mainstream trends in small to midsize cats, we picked a handful of boats to examine. Since the adrenaline factor is at the forefront, lets start with the beach cats.

Hobie Getaway

From its rugged rotomolded construction to its efficient, but simple rotating wing spar, Hobies 16-foot Getaway catamaran is a boat that puts technology to work where it makes most sense without pushing the cost too high. Keeping things simple, in this case, helps keep overall cost in line with the reality of the marketplace.

The objective of the Getaway, designed by Greg Ketterman and the Hobie Cat design group, was to develop a fun family boat with both performance appeal and load-carrying capacity. The keep-it-simple theme kicks off with a built-in keel to add lateral plane and beachability without the complication of daggerboards. The boat is not in the same league as the Hobie Wildcat F18, and if youre a white-knuckle, high-performance sailor who likes to give Jet Skis a run for their money, take a close look at the Tiger or Wildcat. But if youre drawn to the idea of a fun beach cat that is invigorating, easy, and forgiving to sail, the Getaway has plenty to offer.

Three wires comprise the standing rigging, with the headstay carrying an easy-to-handle roller-furling headsail. Like all multihulls, the absence of a backstay allows for a roachy, high-aspect ratio mainsail with plenty of sail area aloft. And with a series of full battens and no boom, this most manageable sailplan makes adapting to multihull sailing a breeze.

The addition of an optional hiking rack/backrest and the “Hobie Bob” masthead float, standard on all boats, lessens the chance of capsize and eliminates the worry about turning turtle. Self-righting is straight forward and one of the biggest checkmarks we gave the Getaway was for its user-friendliness.

Bottom line: If you value ruggedness and ease of use over out-and-out performance, this is an excellent choice.

Weta Trimaran

Photo courtesy of Wilderness Systems

Lightweight materials and plenty of sail area give the little Weta trimaran (reviewed in the May 2008 issue) an ability to get up and go even before whitecaps appear. In many ways, the boat is a blend of high-performance skiff and multihull form stability, delivering an ability to easily alter sail area configurations on the fly. The brilliant adaptation of a sprit and furling reacher allows the crew to kick in an afterburner that turns a sedate afternoon sail into an exhilarating romp.

The pre-sail setup is simple: Install the carbon-tube akas that connect each ama to the main hull, step a light spar, and install the rudder and daggerboard. Carbon-fiber tubes, spars, and blades minimize weight and show how serious the designer and builder are about performance. Five well-placed lines control all three sails, and this little tri has both an easy-to-steer sports car feel, plus the simplicity and stability to get the whole family ready for a ride. The boats lower-volume hulls make it quick to scoot, but not a great load carrier.

Bottom line: Its the right boat for a couple, but two linebacker-sized sailors will wait for 18- to 20-knot conditions before they are off and skimming. That said, this is a great boat for beach multihull sailors looking for more speed.

Windrider Rave

Part contraption, part gifted innovation, this airborne Millennium Flyer is the brainchild of designer Sam Bradfield, and he deserves special recognition for bringing the esoteric to cost-effective production status.

This is definitely not the ideal multihull for every taste, but once youve gone for a sail, its a ride youll never forget. The kayak company Wilderness System creates the amas from rotomolded polyethylene. But what separates the Rave from the rest of the fleet is a clever three-point foil assembly and simple but powerful rig. The result is a bit like putting a super-charged V-8 in Moms Saturn hatchback. (Wilderness Systems also sells a capable non-foil beach trimaran.)

Part of the brilliance of the design is how Bradfield spreads rig loads and foil force into the stiff, strong tubular alloy cross member rather than overloading the more flexible hulls. Once the somewhat complex assembly is complete and the boat launched, departure can be a little anticlimactic. In fact, the ride starts out like a normal outing on a somewhat sluggish trimaran.

However, once the first 15-knot puff hits, theres a little shudder as the wolf strips off its sheeps clothing and rises out of the water onto three innovative foils. In 20-knot conditions, the chop smooths out thanks to the immensely reduced water plane. Soon, youre traveling a little faster than the true-wind velocity, and some adolescent stirrings are rekindled. The first time you enter a jibe on a full plane and exit it at the same speed, youre hooked. The Rave offers a “sit down” windsurfing experience. The speed is exhilarating, and the efficiency of being up on the foils allows the boat to turn less sail area into much more speed over the water.

Bottom line: The reward of double-digit speeds on foils outweighs the hassles of a complicated setup.

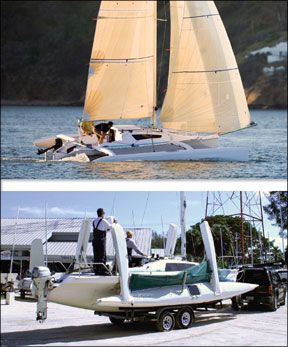

Corsair Dash 750

Many of the features that scored highly in the realm of beach cats are evident in Corsairs latest 24-foot multihull, the Dash 750. The Dash is much more than an upgrade of the popular Corsair 24 MKII. Its a plumb-bowed speedster with a retractable sprit, rudder, and daggerboard that keeps beachability an option while still harnessing the full-throttle performance in a pocket cruiser.

The rotating wing mast sports a good-sized mainsail, and the jib, plus a sprit-mounted roller furling reacher make the sailplan quite versatile and able to adapt to both sides of the wind spectrum. Few pocket cruisers can offer double-digit boat speed in 12 to 14 knots of wind, and with the retractable daggerboard, theres an upwind sailing component thats appreciated by those cruising or racing toward a windward objective.

Corsair honestly refers to the Dashs accommodations as affording “camp-style cruising” and for those out for a weekend or on a longer duration coastal cruise, this may be just fine. Berths, a sink, one-burner stove, and a porta-potty will sound palatial to a backpacker but more than a bit cramped to those contemplating the luxury of a Lagoon.

Bottom line: No, its not The Ritz. But the primary design criterion behind these boats is to unleash easy-to-handle performance, and Corsair has met that goal admirably.

Telstar

This long-lived name for several Tony Smith designs was born in Britain in 1970 as a 26-foot pocket-cruising trimaran. There were three model changes over the 11-year span in which the original boat was built. Production ceased after about 350 hulls when a factory fire destroyed the molds in 1981. This occurred just after the Smith family moved from the United Kingdom to the U.S. and set up shop in Annapolis, Md.

The new company, Performance Cruising Inc., focused on its Gemini line of cruising catamarans. In 2003, after a thorough and thoughtful redesign of the Telstar concept, a new 28-foot trailerable, folding-ama trimaran was launched and named the Telstar 28-soon dubbed the “T2.” The boat packs a cruiser-friendly interior into a soundly built structure that retains a very respectable capacity under sail.

With a fine entry and maximum beam well aft, the center hull conveys a bit of the Gemini legacy, but the vacuum-infused light amas keep the overall weight down, striking a good compromise between comfort and performance.

The flat run aft contributes to this tris willingness to get up and go once the gennaker is unfurled and the crew bears off onto a reach. The boat is easy to steer, and, thanks to a modest amount of mainsail area, sail handling doesn’t require a gymnast or a weight lifter. The boat can be powered efficiently with a 9.9-horsepower outboard, but for those facing calm conditions and a tight schedule, the option of a four-stroke 40- or 50-horsepower outboard can yield 14-knot sprints.

Bottom line: The most cruiser-friendly of the group, the Telstar will appeal to getaway artists who like a turn of speed.

Conclusion

The Hobie brand has led the push to introduce America to sailing ever since the patriarch himself, Hobie Alter, hung up his surf jams and turned from surfboard innovator to multihull maven. His legend lives on, and the new Getaway is another well-targeted success that blends performance, people, appeal, and price.

One of the clear messages behind this boat is that in an economic downturn, you can keep the family sailing without having to belong to a yacht club, lease a marina slip, or need the service of a boatyard. The “hitch and trailer” plan opens up destinations around the country with clean campgrounds and the welcoming breeze off countless bays and lakes. The Hobie Getaway lives up to its name-a boat that may indeed rejuvenate the beach-cat lifestyle.

The Corsair Dash is a more self-contained sailing experience. Large enough to qualify as a three-hulled pocket cruiser, yet performance tuned enough to win point-to-point club races. Shoal-draft cruising destinations or local fun weekends are part of this tris repertoire, and the blend of construction quality, design, agility under sail, and trailerability make it our choice for those seeking great sailing performance in a Spartan pocket cruiser.