The current tally of Island Packets—”More than 1,800 sold”—is impressive for any boatbuilding company. Just over 20 years ago the first boats in the line were built in the Largo (FL) swamps. Known today for their full-foil keels and creamy tan glasswork, and with a reputation for blue-water capability, the IP line has a loyal clientele. Part of the appeal no doubt stems from the long-held notion that full-keel vessels are somehow inherently safer than fin-keelers offshore. Island Packet, more than any other big production builder, has capitalized on this notion from the beginning.

Physically, spiritually, and in just about every other way, Island Packet started with owner/founder Bob Johnson. An M.I.T. naval architect who spent a short honeymoon working on guided missiles for the US Navy, he came to Florida aware that by the end of the ’70s the ascendancy of boats like the Cal 40 had sounded the death knell for old-style full keels. Wine-glass hull forms offered little form stability; oversized keels were dripping with wetted surface, and wimpy aft-end rudders produced wobbly steering at best.

But the new fin-keelers, especially those influenced by the International Offshore Rule, were no bargain, either. They snap-rolled and pounded. They were tender in a breeze, squirrely on the helm, and hard to build. They needed deep draft to be efficient and left props and rudders exposed.

Thought Johnson, “Why not a transition boat—one that fills the area between the types and creates a good cruising boat in the process?”

Call it innovation, stubbornness, or a good sense of the market—in 1979 he designed and built the “missing link” that he envisioned. That stubby, wide-transomed Island Packet 27 was tall on headroom, heavy of displacement, and light on draft and complication. She was capable enough to endear herself first to Suncoast cruisers and then to a wider world. Johnson was in business.

Since then Johnson has, in step-by-step increments, developed a product line: IP-31, 35, 37, 40, etc. Except for the Packet Cat and new Packet Express powerboat project, the company has concentrated on refining and expanding that line of full-keel auxiliaries ever since. In the past 10 years that’s amounted to a new boat every year. Island Packet has won “Boat of the Year” awards in five of the past six years.

Says Director of Sales and Marketing Bill Bolin, “Bob starts from scratch every time. These aren’t cookie cutter designs.”

Nonetheless, they have the same basics: U-shaped hull, “full-foil” keel, balanced rudder, similar underwater profiles, low aspect ratio/cutter- rigged sailplans, and much more room below than you’d expect.

Introduced in 1997 and the first of the line to be built with a contemporarily styled swim platform, the Island Packet 350 is a rock-solid structure with a great deal of elbow room. As such it has to pay something to the piper when it comes to responsiveness under sail, especially in light air.

DESIGN

Plumb transoms gave the earliest Island Packets something of a chopped-off look. The IP 350’s swim platform, while it clashes a bit with the traditional personality of the boat, balances her ends visually. It also extends her waterline length and thus increases her top-end speed under both sail and power. And of course it’s useful for getting into and out of the water (or dinghy).

Her freeboard seems more proportional to her length than some of her smaller cousins. She’s not as boxy as they are, but she still sits substantially atop her boot top. In comparison to larger Island Packets (like the 42 and 45) she has a flatter sheer. To our eye her look is businesslike and a bit severe compared to some of the curvier members of the family.

In combination with her robust ballast/displacement ratio of 47%, her hull shape gives her form stability and makes her very stiff. She also, thanks to the way her displacement is arranged, can carry a formidable payload—it takes a lot of extra weight to sink her below her lines. There’s not only “a place for everything” in an Island Packet, but also the muscle to tote it.

The 350’s hull sections are slimmed a bit as they come aft, but she still has substantial haunches. Fullness aft (in combination with a powerful balanced rudder) suits her well to handle surfing and quartering seas and also gives her the power to carry substantial sail in a blow.

Forward she’s fuller than most modern auxiliaries, but one of Johnson’s refinements (the 350 replaced the Island Packet 32) was to lengthen her overhang and make her entry a bit finer in the interest of better speed, drier sailing, and more usable space on deck. The boat is beamier (12′) than most, but her waterlines are faired nicely and the transition between her sections is smooth.

Her cutter rig is a design element that sets the 350 and her Island Packet sisters apart. The mast is relatively far aft in the boat; the chainplates are outboard; genoa and staysail (the latter fitted with the self-vanging Jib Boom patented by Garry Hoyt) are on furlers forward.

The company’s ad copy calls it “a rig suited to a wide range of conditions.” Experience suggests that the range is indeed wide, but that shouldn’t be interpreted to mean “all-encompassing.” Wind abeam and boat speed mounting, you need only roll out the staysail to cement in an extra knot or so and delight in the power of easily-deployed sail. However, short-tacking up a narrow channel trying to shoehorn an over-sized genoa between forestay and headstay and make the boat point when the jib is trimmed to extravagantly wide sheeting angles (all the while wondering what to do with your self-tending but nigh irrelevant staysail), is another story, making it easy to grasp why the cutter rig has, for most builders, gone the way of high-button shoes.

Still, a wide shroud base does make for uncluttered walkways and easily secured chainplates. and the three-sail plan offers plenty of options for shortening sail and balancing the sailplan. In short, the cutter rig means sacrificing some performance and convenience upwind, but it has proven well-suited to the kind of sailing that most cruisers do.

Full keels are something of a religion with the most messianic Island Packet owners. They celebrate their shallow draft, “reef-crunching” planform, and solid sea-keeping. A “seamless” hull with encapsulated ballast offers commodious tankage and excellent dry bilge stowage. And, of course, there’s the emotional tie with “good old boats” and the way things used to be.

There’s a reason, however, that the vast majority of boats built today, even those built as deep-sea cruisers, are designed with some form of fin keel. Aspect ratio (the relationship between leading edge length and foil area) is the prime determinant of lift. Put simply, a foil develops lift in proportion to the square of its draft. Fore-and-aft area thus does precious little to make a foil work when it comes to helping a boat to windward. When it comes to lift/drag characteristics, fins win, by a sizable margin.

There’s more to a keel than lift/drag, to be sure. Johnson uses NACA foil sections to develop his “full foil” shapes. This minimizes parasitic drag and maximizes lift. The stiffness of his boats makes his keels work better. Still, a long keel is fated by design to be less efficient to windward than a fin.

CONSTRUCTION

Island Packet boatbuilding is a blend of what’s new with the tried and true. Johnson, for example, designs each boat “the old way” with hand-faired lines lofted into full-sized Mylar templates that are used to cut mahogany molds to make the plugs for each hull. “He doesn’t have a computer on his desk,” Bill Bolin says.

Still, the company is at the cutting edge on several fronts: it was the first US sailboat builder to be certified “Class A” for sale in the European Community, and it’s a leader in developing standards to meet the “maximum achievable control technology” (MACT) air quality regime soon to be enacted under the Environmental Protection Agency. It also developed its own gelcoat and offers a 10-year warranty against blistering. Island Packet developed a home-grown core material (the same through 22 years) that the company also warrants for 10 years, and it pioneered the use of “power rollers” to reduce fumes and overspray during the wetting-out process.

The 350’s hull is solid, made from a layer of mat and three layers of knitted tri-axial glass. The forward edge of the keel is built up to more than an inch in thickness. The glass/ resin ratio averages about 58:42. “I’d like to see that come down,” Johnson says, but, especially given the tight curve of the 350’s bilge where controlling the cure is difficult, that result is more than acceptable.

The underwater gelcoat uses vinylester resin, much the best type for blister protection. The rest of the boat is laid up with general purpose polyester resin.

Island Packet hulls are reinforced with structural grids. Fiberglass on top, they sit atop plywood floors that are tabbed to the hull. The grid is glassed to the hull and bulkheads are taped in atop that foundation. It’s a time-honored (and time-consuming) way to build.

The deck is cored. It’s over an inch thick and joined (via a solid lip) to an inward-turning flange atop the hull with 3M 5200 sealant and 1/4″ stainless steel bolts on 6″ centers. A teak toe rail goes atop that assembly and it is bolted through a 1/4″ aluminum backing plate.

The chainplate anchors are stainless angles welded to the underdeck flange and tied to the hull with a fan of fiberglass taping that extends virtually to the turn of the bilge. The 4″ by 1/2″ steel bars that support the motor mounts are over-sized by any standards. Deck hardware is bolted aboard through beefy aluminum backing plates.

The 350 has a 2″ stainless steel rudder shaft upon which rides a steel weldment. Some owners have had problems with their rudders: The foam inside the fiberglass skins has, in some cases, developed voids, deformation, and or caused delamination. Says Bolin, “We’re much more conscious of sealing the seam between the rudder halves than we used to be. That, and monitoring the foam for voids along with measuring each rudder that we build in a jig for exact shape has done a lot to cure the problem.”

A great way to get into the Island Packet family.

A great way to get into the Island Packet family.

Market Scan Island Packet 350

1998 Island Packet 350 (SOLD) Jan Guthrie Yacht Brokerage

$114,900 847-338-8808

Racine WI Jan Guthrie Yacht Brokerage

1999 Island Packet 350 CJ Yacht Sales

$129,900 850-783-1143

Beaufort NC Yachtworld

1998 Island Packet 350 Crusader Yacht Sales

$122,000 410-883-7361

Solomons MD Yachtworld

The 350 is bulkier, beamier, and longer (34′ 8″ on deck) than most boats in her class, but that didn’t prepare us for how much roomier she is than the average 35-footer. “Liveaboard” is a flexible term, but until we sailed aboard the IP 350 we’d never thought of applying it to a boat of this LOA. She has the volume, the organization, and the systems to qualify.

The layout belowdecks makes maximum use of the room she affords. The bulkhead table seats six and makes the saloon a model of two-way space. Angling the two double berths across the fore and aft axis saves sole space and makes both cabins more than habitable. The settees in the saloon need leecloths to become sea berths; the other cabins aren’t fit for sleeping underway.

Saloon and galley are jumbo- sized. The head has double doors and offers a clever shower plus more than enough room for genuine comfort. A portion of the head is designated as a wet locker, which always makes good sense.

Stowage is everywhere, and it’s good stowage: watertight bins below berths and seats; cockpit lockers with escape latches in case you lock yourself in; fiddles where you’ll need them; and slick (positive action) pushbutton closures on everything, including the garbage bin. There are line boxes, cold boxes, and convenient pockets as well as cavernous bins in the cockpit.

Lights are thoughtfully provided in the bilge, the ice box, the cockpit lockers, the companionway, and the engine room. Five ports per side plus four overhead hatches make for good ventilation.

Ice boxes are a focus for what little belowdecks discontent IP owners express. “It’s too deep to get to the bottom of it,” “It’s poorly insulated,” and “It needs a gasketed lid,” are the refrains. Says Bolin, “It’s a big box, but not too big. We hang the inner box inside a wooden support box and then fill in the space between with urethane foam. Occasionally an air void develops in the foam, but we check each unit as we build it and back fill to remove any spaces. What used to be a teak-to-teak gravity seal for the top is now an insulated part (with urethane foam) that is hinged and gasketed.”

No matter the complaint, however, owners are universally positive about the help that they’ve received from the factory and especially from Customer Service Manager Tom Broome. “He’s a jewel,” writes one, and many second that praise.

PERFORMANCE

There wasn’t much air when we left Falmouth (MA) Inner Harbor aboard Neil and Sandie Bernstein’s IP 350 Pipe Dream. We took the opportunity to maneuver under power. She backed relatively straight and turned in a tighter circle than expected.

Turning in her own length seemed just barely possible, but it took bigger bursts of power than we would have used to spin a fin-keeler. While her long keel should keep her head from falling off in a crosswind, we needed to wait for the breeze to come up to perform that test.

We didn’t expect this heavy, beamy, long-keeled cutter to shine in light air, and she didn’t. While the puffs fluctuated from 2 knots to 5, our speed varied hardly at all. The pulse of life and acceleration that’s at the heart of light-air sailing was weak. Once we put the boat on the wind, eased sheets a bit, and sailed full and by, however, she began to make a bit of wind for herself and enjoyed a kind of momentum that took her through the flat spots and over the rough patches. She proved the old dictum about heavy boats in light air—once you get them moving, they’re hard to stop.

We criss-crossed Nantucket Sound in a building sou’wester. The IP 350 has plenty of sail area, yet is a notably stable platform. She can reach and run with the best of them, despite the added wetted surface of her keel.

She won’t surf easily and surge above her hull speed, but for the sort of passagemaking that cruisers do, and for everyday sailing like we were doing, she has fine performance potential. Says Bolin, “Island Packets have won the Caribbean 1500 and Marion-Bermuda Races. Bob Johnson sailed an IP 350 to first in class and second overall in the Annapolis-Newport Race. They’re long-legged boats.”

But reaching and running are not the complete package. It was kicking up to and over 12 knots as we put the boat back on the wind. A few minor tweaks and it was hands off the wheel. She steered herself for five-minute stints, wavering little and maintaining good speed when left to her own devices. Chalk one up for the long keel.

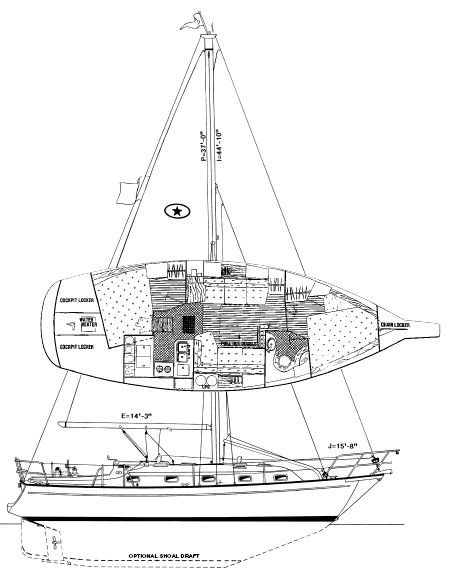

| Island Packet 350 | Courtesy: Sailboatdata.com |

|---|---|

| Hull Type: | Long Keel |

| Rigging Type: | Cutter |

| LOA: | 34.67 ft / 10.57 m |

| LWL: | 29.33 ft / 8.94 m |

| S.A. (reported): | 725.00 ft² / 67.35 m² |

| Beam: | 12.00 ft / 3.66 m |

| Displacement: | 16,000.00 lb / 7,257 kg |

| Ballast: | 7,500.00 lb / 3,402 kg |

| Max Draft: | 4.25 ft / 1.30 m |

| Construction: | FG |

| First Built: | 1997 |

| Last Built: | 2004 |

| Builder: | Island Packet Yachts (USA) |

| Designer: | Bob Johnson |

| Make: | Yanmar |

| Model: | 3JHE |

| Type: | Diesel |

| Fuel: | 50 gals / 189 L |

| Water: | 100 gals / 379 L |

| S.A. / Displ.: | 18.34 |

| Bal. / Displ.: | 46.88 |

| Disp: / Len: | 283.1 |

| Comfort Ratio: | 29.21 |

| Capsize Screening Formula: | 1.91 |

| S#: | 1.76 |

| Hull Speed: | 7.26 kn |

| Pounds/Inch Immersion: | 1,257.59 pounds/inch |

| I: | 44.83 ft / 13.66 m |

| J: | 15.67 ft / 4.78 m |

| P: | 37.00 ft / 11.28 m |

| E: | 14.25 ft / 4.34 m |

| S.A. Fore: | 351.24 ft² / 32.63 m² |

| S.A. Main: | 263.63 ft² / 24.49 m² |

| S.A. Total (100% Fore + Main Triangles): | 614.87 ft² / 57.12 m² |

| S.A./Displ. (calc.): | 15.55 |

| Est. Forestay Length: | 47.49 ft / 14.47 m |

They began as wavelets and never built to a true “sea,” but the waves we encountered illustrated another of the boat’s strong points. “Momentum” would be one way to put it; “wave-crushing” would be another. In this moderate breeze our 35-footer moved with commanding solidity through the chop. The IP 35’s motion is minimal, predictable, and comfortable.

Close-windedness and efficiency upwind are the IP 350’s weakest suits. To build an upwind rocket Johnson would have to lighten the boat considerably, make her narrower, especially up forward; arrange for narrower sheeting angles, and probably abandon his full-foil keel. Then his boats would look like everyone else’s. Instead he charges ahead with the “missing links” that he’s been forging with success for more than 20 years.

The asking price for the 1998 Island Packet 350 pictured here was $114,000 at press time.

Contact- Island Packet Yachts, 1979 Wild Acres Rd., Largo, FL 33771; 888/724-5479; www.ipy.com.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Owner Comments.”

This review was first published September 19, 2001 and has been updated.

Thank you for a very helpful review. Count me a fan of IPs. As modern sailboats(monohulls) continue to devolve, I appreciate IP more and more.

That’s a proper, highly detailed boat review. Not just a listing of amenities and interior storage, but full of construction and hardware details. All the main concerns a person considering a cruising blue water biat needs to know. The comforts are of less concern, and can all be tweaked. I want to know it’s safe first, livable second. Kudos on the details.